Southern Prose and Poetry for Schools:

Electronic Edition.

Ed. by Mims, Edwin, 1872-1959.

Ed. by Payne, Bruce Ryburn, 1874-1937.

Funding from the University of North Carolina Library supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Risa Mulligan

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Amanda Page, and Sarah Ficke

First edition, 2006

ca. 740K

University Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2006.

Source Description:

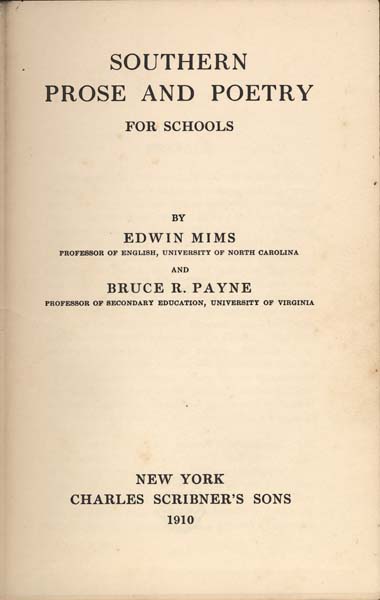

(title page) Southern Prose and Poetry for Schools

(cover) Southern Prose and Poetry

Edwin Mims

Bruce R. Payne

xii, 440 p.

New York

Charles Scribner's Sons

1910

Call number PS551 .M4 (Davis Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

This electronic edition is a part of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill digital library, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes appear as in the original text, except for the poetry section, in which they have been moved to the end of the poem and renumbered accordingly.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

Revision History:

- 2006-,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2006-08-28,

Sarah Ficke

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2005-01-13,

Amanda Page

finished TEI/SGML encoding.

- 2004-09-27,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

[Half-Title Page Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

SOUTHERN

PROSE AND POETRY

FOR SCHOOLS

SOUTHERN

PROSE AND POETRY

FOR SCHOOLS

BY

EDWIN MIMS

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA

AND

BRUCE R. PAYNE

PROFESSOR OF SECONDARY EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1910

Page verso

COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Page v

PREFACE

THE principal purpose of this collection is to inspire the youth of the South to a more earnest and intelligent study of the literature of that section. For various reasons the Southern student knows less of his own literature than he does of any other. One rarely hears of the study of a Southern author in a Southern high school or grammar school. Without diminishing the effort devoted to the study of American literature, and with no intention of sectional glorification, our boys and girls should begin to acquaint themselves with some of the finer spirits who have endeavored to record in beautiful language the emotional experiences peculiar to the section in which they dwell. The definite task undertaken in this volume, therefore, is to provide students with a convenient introduction to the work of Southern writers. Because the literature of the South is a part of the Nation's literature, it is believed that these stories and poems will be studied with profit and pleasure by students from all sections of our country.

The book is intended primarily for schools. The exact position in the curriculum it shall occupy is left to the judgment of school officials. Intellectual aptitudes and previous training vary so greatly among different groups of students and in different sections that the editors do not care to undertake to decide the definite place in a system of schools for such a collection.

Page vi

It is never too late to acquaint one's self with a masterpiece of literature, however simple the composition; on the other hand, one has a right to read a classic just as early as it may be understood with a fair degree of accuracy and enjoyment. With these principles in mind, it is the belief of the editors that this volume may furnish supplementary reading in the upper grammar grades, parallel reading throughout the high-school course, and suggestive reading for a college class in American literature. For more detailed study, a special term of months might profitably be devoted to it in the high school and the college.

If criticism is offered because of the omission of favorite authors, we can only suggest that this is no compendium of Southern literature. It was impossible to include everything, and those selections were made which, in the judgment of the editors, would hasten the establishment of a point of contact between the youthful student and that great world of literature to which we hope to introduce him.

The grouping of the stories and poems should be of assistance to the pupil. The usual chronological arrangement has been abandoned; selections have been assembled with reference to a central idea, both for the sake of clearness of apprehension and for the purpose of sustaining interest.

The profuse use of notes has been avoided. No explanation has been made of any word that may be found in an academic dictionary. To the adolescent mind in the initial stage of acquiring a taste for literature nothing is so tiring as over-analysis and annotation. If abundant notes seem necessary at this period, there is ground for suspicion that the material is not adapted to the age of the learner. The teacher with a dictionary

Page vii

and a manual of mythology is the best judge of the limit of endurance of the mechanical and formal in the study of this subject.

In the back of the book will be found biographical sketches of the authors. These appear alphabetically and in the briefest possible form, each name being followed by a complete list of the writings of the author. If the teacher wishes to pursue such study further any good text in Southern literature will be helpful. The following works are of value: Southern Writers, by W. P. Trent; Southern Writers (vols I and II), by W. M. Baskerville; The Library of Southern Literature (13 vols); The South in the Building of the Nation (10 vols). To all of these works the editors express their obligation.

Kind permission for the use of copyrighted materials has been granted by the following publishers and writers or representatives of writers, due acknowledgment of which has been made at the proper places in the text: Doubleday, Page and Company, The Macmillan Company, Charles Scribner's Sons, The Houghton, Mifflin Company, P. J. Kenedy and Sons, Lothrop, Lee and Shepard, Small, Maynard and Company, Stone and Barringer, D. Appleton and Company, B. F. Johnson Publishing Company, The Century Company, G. P. Putnam's Sons, Frederick A. Stokes Company, Yvon Pike, and William Gordon McCabe.

Page ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION . . . . .3

-

I. STORIES AND ROMANCES

- THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 23

- THE DOOM OF OCCONESTOGA . . . . . WILLIAM GILMORE SIMMS . . . . . 50

- THE FIRST PLAY ACTED IN AMERICA . . . . . JOHN ESTEN COOKE . . . . . 70

- THE CAPTURE OF FIVE SCOTCHMEN . . . . . JOHN PENDLETON KENNEDY . . . . . 79

- EARLY SETTLERS . . . . . JOHN JAMES AUDUBON . . . . . 89

- THE TALE OF A "LIVE OAKER" . . . . . JOHN JAMES AUDUBON . . . . . 93

- THE KEG OF POWDER . . . . . DAVID CROCKETT . . . . . 98

- THE BEAR HUNT . . . . . DAVID CROCKETT . . . . . 102

- THE BURIAL OF THE GUNS . . . . . THOMAS NELSON PAGE . . . . . 109

- FREE JOE AND THE REST OF THE WORLD . . . . . JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS . . . . . 139

- JEAN-AH POQUELIN . . . . . GEORGE WASHINGTON CABLE . . . . . 156

- ON TRIAL FOR HIS LIFE . . . . . JOHN FOX, JR. . . . . . 185

- THE STAR IN THE VALLEY . . . . . CHARLES EGBERT CRADDOCK . . . . . 197

- ON A DAY IN JUNE . . . . . JAMES LANE ALLEN . . . . . 224

- A SOUTHERN HERO OF THE NEW TYPE . . . . . ELLEN ANDERSON GHOLSON GLASGOW . . . . . 227

- II. POEMS

- NATURE POEMS

- ETHNOGENESIS . . . . . HENRY TIMROD . . . . . 241

- LAND OF THE SOUTH . . . . . ALEXANDER BEAUFORT MEEK . . . . . 242

- THE COTTON BOLL . . . . . HENRY TIMROD . . . . . 244

Page x - SPRING . . . . . HENRY TIMROD . . . . . 249

- THE SONG OF THE CHATTAHOOCHEE . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 252

- ASPECTS OF THE PINES . . . . . PAUL HAMILTON HAYNE . . . . . 254

- THE LIGHT'OOD FIRE . . . . . JOHN HENRY BONER . . . . . 255

- OCTOBER . . . . . JOHN CHARLES MCNEILL . . . . . 256

- AWAY DOWN HOME . . . . . JOHN CHARLES MCNEILL . . . . . 258

- TAMPA ROBINS . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 260

- THE WHIPPOORWILL . . . . . MADISON CAWEIN . . . . . 261

- TO THE MOCKING-BIRD . . . . . ALBERT PIKE . . . . . 262

- ALABAMA . . . . . SAMUEL MINTURN PECK . . . . . 265

- THE GRAPEVINE SWING . . . . . SAMUEL MINTURN PECK . . . . . 266

- TRIBUTES TO SOUTHERN HEROES

- VIRGINIANS OF THE VALLEY . . . . . FRANCIS ORRERY TICKNOR . . . . . 268

- THE BIVOUAC OF THE DEAD . . . . . THEODORE O'HARA . . . . . 269

- ODE . . . . . HENRY TIMROD . . . . . 273

- JOHN PELHAM . . . . . JAMES RYDER RANDALL . . . . . 274

- ASHBY . . . . . JOHN REUBEN THOMPSON . . . . . 276

- A GRAVE IN HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY . . . . . MARGARET JUNKIN PRESTON . . . . . 277

- THE SWORD OF ROBERT LEE . . . . . ABRAM JOSEPH RYAN . . . . . 277

- NARRATIVES IN VERSE

- POEMS OF LOVE

- TO HELEN . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 305

- ULALUME . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 306

- ANNABEL LEE . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 309

- TO ONE IN PARADISE . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 311

- MY SPRINGS . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 312

- EVENING SONG . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 314

- FLORENCE VANE . . . . . PHILIP PENDLETON COOKE . . . . . 315

Page xi - MY STAR . . . . . JOHN BANISTER TABB . . . . . 316

- THE HALF-RING MOON . . . . . JOHN BANISTER TABB . . . . . 317

- PHYLLIS . . . . . SAMUEL MINTURN PECK . . . . . 317

- A HEALTH . . . . . EDWARD COATE PINKNEY . . . . . 319

- DREAMING IN THE TRENCHES . . . . . WILLIAM GORDON MCCABE . . . . . 320

- REFLECTIVE POEMS

- POE'S COTTAGE AT FORDHAM . . . . . JOHN HENRY BONER . . . . . 323

- ISRAFEL . . . . . EDGAR ALLAN POE . . . . . 325

- A COMMON THOUGHT . . . . . HENRY TIMROD . . . . . 327

- MY LIFE IS LIKE THE SUMMER ROSE . . . . . RICHARD HENRY WILDE . . . . . 328

- A BALLAD OF TREES AND THE MASTER . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 329

- NATURE POEMS

- III. LETTERS

- TO HIS DAUGHTER . . . . . THOMAS JEFFERSON . . . . . 333

- TO JEFFERSON SMITH . . . . . THOMAS JEFFERSON . . . . . 335

- TO HIS SISTER . . . . . THOMAS JEFFERSON . . . . . 336

- TO GOVERNOR LETCHER . . . . . ROBERT EDWARD LEE . . . . . 337

- TO THE TRUSTEES OF WASHINGTON COLLEGE . . . . . ROBERT EDWARD LEE . . . . . 338

- TO. MRS. JEFFERSON DAVIS . . . . . ROBERT EDWARD LEE . . . . . 339

- TO HIS DAUGHTER . . . . . ROBERT EDWARD LEE . . . . . 341

- TO A FRIEND . . . . . MRS. ROGER PRYOR . . . . . 343

- TO A FRIEND . . . . . MRS. ROGER PRYOR . . . . . 346

- TO HIS FATHER . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 351

- TO HIS WIFE . . . . . SIDNEY LANIER . . . . . 352

- IV. ORATIONS AND ADDRESSES

- THE COMPROMISE OF 1850 . . . . . HENRY CLAY . . . . . 357

- CONCLUSION OF LAST SPEECH . . . . . JOHN CALDWELL CALHOUN . . . . . 360

- EULOGY ON CHARLES SUMNER . . . . . LUCIUS QUINTUS CINCINNATUS LAMAR . . . . . 363

- ABRAHAM LINCOLN . . . . . HENRY WATTERSON . . . . . 372

- THE NEW SOUTH . . . . . HENRY WOODFIN GRADY . . . . . 375

Page xii - SECTIONALISM AND NATIONALITY . . . . . EDWIN ANDERSON ALDERMAN . . . . . 388

- EDUCATION AND PROGRESS . . . . . BENJAMIN HARVEY HILL . . . . . 401

- THE SCHOOL THAT BUILT A TOWN . . . . . WALTER HINES PAGE . . . . . 405

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES . . . . . 421

Page 1

INTRODUCTION

Page 3

INTRODUCTION

IN the compilation of this volume the effort has been made to present some of the most important forms of prose and poetry. There will be found short stories, selections from historical romances, poems, essays, letters, and orations.

First in point of interest are the short stories and the selections from historical romances, and first among these is Poe's Fall of the House of Usher. Poe's originality in defining, by theory and practice, the type of short story gives him the pre-eminent position among the short-story writers of the South, and indeed of America. In his review of Hawthorne's Twice Told Tales in 1842 he wrote the best statement of the province of this type of fiction, and gave the best analysis of his own tales:

"The ordinary story is objectionable from its length, for reasons already stated in substance. As it cannot be read at one sitting, it deprives itself, of course, of the immense force derivable from totality. Worldly interests intervening during the pauses of perusal modify, annul, or contract, in a greater or less degree, the impressions of the book. But simply cessation in reading would, of itself, be sufficient to destroy the true unity. In the brief tale, however, the author is enabled to carry out the fulness of his intention, be it what it may. During

Page 4

the hour of perusal the soul of the reader is at the writer's control. There are no external or extrinsic influences--resulting from weariness or interruption.

"A skilful literary artist has constructed a tale. If wise, he has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents; but having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents--then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this pre-conceived effect. If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step. In the whole composition there should be no word written of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design. As by such means, with such care and skill, a picture is at length painted which leaves in the mind of him who contemplates it with a kindred art a sense of the fullest satisfaction. The idea of the tale has been presented unblemished, because undisturbed; and this is an end unattainable by the novel. Undue brevity is just as exceptionable here as in the poem; but undue length is yet more to be avoided."

The Fall of the House of Usher is a full realization of Poe's ideal as expressed in this quotation. It is the most typical of his stories--in its plot, its background, and its characters. The "totality of effect" insisted upon as characteristic of every story is produced in an impressive way in this tale. The story has no definite location on the map; and yet every detail of the background contributes to the climax. The singularly dreary tract of country, the black and lurid tarn, the

Page 5

vacant eye-like windows, the few rank sedges, the white trunks of decayed trees, the gothic archway of the hall, the sombre tapestries of the walls, the ebon blackness of the floors, the phantasmagoric armorial trophies, the encrimsoned light and trellised panes of the windows--all these serve to render the total effect of the story startlingly impressive. Usher and his sister, like the heroes and heroines of Poe's other stories, are not flesh and blood characters, but rather fantastic creations of his own weird imagination. The general theme of the story--the passing away of a beautiful and fragile woman--is also characteristic, as is also the pellucid and at times highly colored style. If in his poetry Poe suggests comparison with Coleridge, in his prose one oftenest thinks of De Quincey. If at times he can be as clear cut in his style as the most extreme realist, at other times there is all the charm of melody and color. The pursuit of perfection in phrase and form was one of his most characteristic passions. After all, this is his great bequest to American, and especially to Southern, literature. Hawthorne's story, The Artist of the Beautiful, is an admirable interpretation of Poe's life and art. Nowhere else in these selections will there be seen such felicity and finality of style and such perfection of literary form as in The Fall of the House of Usher. In no other Southern stories is there such a steadfast adherence to the demands of art for art's sake.

There is little of the Southern landscape or character in Poe's poetry or prose. His imagination found a home only in far off lands, sometimes even in the Middle Ages, or yet again in the fantastic places of his own mind

Page 6

as it went voyaging through strange seas of imagination alone. "He haunted a borderland between the visible and the invisible, a land of waste places, ruined battlements, and shadowy forms, wrapped in a melancholy twilight."

And yet there is a sense in which Poe was Southern, in temperament, and even in art. One may not go so far as a recent American critic when he says that Poe was as much the product of the South as Whittier was of New England, and still maintain that he has a distinct place among Southern writers. Though born in Boston he spent his youthful days in Richmond, as an adopted son in a family that was in close touch with the best elements of Southern life. At a Richmond classical school he received that classical training which was particularly characteristic of the ante-bellum South. He resided for one scholastic year at the newly established University of Virginia, where he added to his knowledge of the classics an intimate study of modern literature. In Baltimore he received his first recognition when the committee of which John P. Kennedy was a member discovered his genius as a poet and as a writer of short stories. In 1835 he became editor of the most distinctively Southern magazine, the Southern Literary Messenger, in which he published some of his best tales and his criticisms of contemporary writings. It is in his critical writings that Poe's Southern bent of mind was most notably evinced; for here he manifested a characteristic prejudice against New England writers and a corresponding sympathy with Southern writers. "He always lived in the North as an alien," says Professor

Page 7

Woodberry, "somewhat on his guard, somewhat contemptuous of his surroundings, always homesick for the place that he well knew would know him no more though he were to return to it." No apology need therefore be made for including him among Southern writers.

More characteristic of the South, however, were those romances in which William Gilmore Simms, John P. Kennedy, John Esten Cooke, and later writers, realizing the wealth of material in Southern history and tradition, wrought out their stirring historical romances. The selections from these romances, included in this volume, suggest various periods of Southern and national history. The historical background of Simms's The Yemassee is the conflict between the Indians and the English colonists of South Carolina about the year 1715. Simms's early life fitted him pre-eminently for the rôle of a romancer. The stories of the Revolutionary War and of the early colonial era, told to him by his grandmother, the weird tales of ghosts and witches which he gathered from other story-tellers, and his actual contact with pioneers and Indians in the South-west--all stimulated in him a natural fondness for stirring, romantic themes. This temperament, enhanced by study of colonial history and traditions, culminated in The Yemassee, and in his romance of the Revolution, The Partisan.

A better story of the Revolutionary era, however, is Horse-Shoe Robinson, published in 1835 by John P. Kennedy. The selection given from this book presents some idea of the romantic warfare carried on by the mountaineers of North and South Carolina against

Page 8

the despotism of the Tory ascendancy. The elemental humanity, the courage, the resourcefulness, and the perseverance of Horse-Shoe Robinson are suggested in Kennedy's characterization of him and in the capture of the five Scotchmen with the aid of a brave and adventurous lad.

John Esten Cooke, who is more popularly known by his stories of the Civil War, is represented by a citation from his earliest book, The Virginia Comedians, or Old Days in the Old Dominion, the background of which is the era just preceding the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. The scene is laid in Williamsburg at the time when the new forces of freedom and democracy were struggling against the Established Church and the feudal system of society which then prevailed in Virginia. Perhaps the most interesting part of the novel is the account given of the acting of the first play ever performed in America, The Merchant of Venice.

While they do not belong strictly to this section of the book, the editors have thought well to put here the selections from Audubon and Crockett, as giving better than any fiction the real spirit of the pioneer days.

Of the stirring incidents of the Civil War, Mr. Thomas Nelson Page's Burial of the Guns gives a most striking suggestion. The story is complete in itself, and in its presentation of the heroism and tragedy of that fateful era leaves little to be said. The time has not yet come when the full meaning of that great struggle can be suggested in dramatic or romantic form, but the stories of Mr. Page, notably Marse Chan and Meh Lady, are clearly an anticipation of greater work yet to be

Page 9

done. The transition from the old order to the new is best seen in the novels of another Virginia writer, Miss Ellen Glasgow. The Voice of the People, from which a selection is given, is not only a work of art, but is a real contribution to the interpretation of the present South.

Distinctly different in type and in quality from Poe's stories and from the selections from historical romances are the short stories of Southern writers which have to do with local scenes and characters. The short story after the Civil War had to do principally with the characteristics of the various sections and even States of the Republic. Bret Harte, in his stories of Western life, inaugurated a new era in American fiction. A host of American writers have followed his lead in exploring the different sections and in explaining the people of one State to the people of the others. The short story has become the national mode of utterance in the things of the imagination. In the absence of any truly national novel, which has so long been the ideal of American story writers and critics, these short stories of local color have served to reveal provincial types and local scenes. With their contemporaries in all sections of the country the Southern writers have wrought to this end. About 1875 their short stories began to appear in Northern magazines. Gradually they revealed all the picturesque phases of Southern life and scenery. Their writings have served to reveal the South to itself and to the nation. To these authors literature has been a profession and not a pastime. They have written with discipline and restraint, and the best of

Page 10

them take their rank among the best contemporary writers of America.

In some of the short stories that are selected as typical the interest is that of the character sketch. From Southern stories and novels there might be gathered passages which would be a complete portrait gallery of Southern men and women. In the stories of Joel Chandler Harris, Charles Egbert Craddock, Thomas Nelson Page, George W. Cable, James Lane Allen, and John Fox we have a great variety of types--the old-time negro, the Southern gentleman and lady, the Creole, the mountaineer, and the Kentuckians of the blue-grass country. In these provincial types, and especially in Free Joe and Jean-ah Poquelin, we have the portrayal of that elemental nature which makes the whole world kin.

In other stories the chief point of interest is the delicate handling of landscape. Southern writers have been quick to realize the wealth of natural scenery that awaited writers with seeing eyes and portraying hands. No writer has displayed greater power of description than Miss Murfree, from whose stories a series of masterly paintings might be sketched. In The Star in the Valley the mountains play an important rôle. They, along with the trees, the sun, moon, and stars, are not merely spectators but participants. In fact, one feels at times that the author has let her undoubted ability of description interfere with her dramatic presentation of characters. She lingers over the setting of her pictures too long; and yet in this way she has ministered to one

Page 11

of the essential appeals made by modern fiction--the feeling for landscape.

The same point may be made with regard to the exquisite landscapes of Mr. James Lane Allen's stories. Nature is an important character in his Kentucky Cardinal, The Choir Invisible, and the Summer in Arcady. Her influence streams through the story, sometimes serving as a background, but oftener as a sort of chorus to the drama of human nature. His ability to describe and interpret nature may well be seen in the selection entitled On a Day in June. Only the careful reading of all his stories will give one any adequate idea of the poetic glamour which he has cast over those fair regions, or his romantic, and even transcendental, attitude to nature.

Surely no American writer ever had a finer background for his stories and novels than George W. Cable. In his Old Creole Days and The Grandissimes we have the artistic blending of scenery, architecture, and romance. Now it is the rich luxuriance of the swamps and bayous, now the Rue Royale--a long narrowing perspective of arcades, lattices, balconies, dormer windows, and blue sky--and yet again some large old Creole mansion that survives as a reminder of the romantic past.

It must not be thought, however, that these story writers, in suggesting the wealth of natural scenery and human nature, are lacking in the ability to construct artistic plots. None of them equals Poe in his ability to produce a single startling plot. And yet the short stories that are presented in this book deserve to rank,

Page 12

even from the stand-point of artistic structure, among the best American stories.

Aside from all question of local background or types of human nature or plot, Southern fiction is pre-eminently the product of the Southern temperament. A writer in the Atlantic Monthly, reviewing Southern fiction as a whole, said in 1885: "It is not the subjects offered by Southern writers which interest us so much as the manifestation of a spirit which seemed to be dying out of our literature. . . . We should not be greatly surprised if the historian of our literature a few generations hence should take note of an enlargement of American letters at this time through the agency of a new South. . . . The North refines to a keen analysis, the South enriches through a generous imagination. The breadth which characterizes the best Southern writings, the large free handling, the confident imagination, are legitimate results of the careless yet masterful and hospitable life which has pervaded that section. We have had our laugh at the florid, coarse-flavored literature which has not yet disappeared at the South, but we are witnessing now the rise of a school that shows us the worth of generous nature when it has been schooled and ordered."

The same may be said of the best Southern poetry, which forms the second part of this volume. The selections have been arranged in groups rather than chronologically or according to their authors. They are printed in the following divisions: nature poems, tributes to Southern heroes, narratives in verse, love poems, and reflective poems. It will be seen that these

Page 13

subjects indicate the various appeals that poetry makes to the human heart. For a long time the writing of poetry was at a discount in the South. The author of one of the most popular ante-bellum lyrics was urged by his friends never to have anything to do with poetry--advice that was typical of the attitude of many Southerners. Those who did write poetry paid little heed to the human life or nature about them. Their poetry was likely to be sentimental and in its choice of subjects remote from the interests of everyday life. Following the lead of Byron, they had a view of life which was melancholy and at times morbid.

Even in the ante-bellum period, however, there were some poems that suggested the characteristic land-scapes of the South. We find such poems in Meek's Land of the South, Timrod's Cotton Boll, and in poems on the mocking-bird by Albert Pike, Meek, and Richard Henry Wilde.

The writers of the new South have, like the short-story writers already mentioned, been far more sensitive to local influence. Paul Hamilton Hayne, after the Civil War, lived at Copse Hill, near Augusta, Georgia. His devotion to poetry under so many adverse circumstances is one of the finest traditions of American literary history. He lived in a cabin of his own building--an extraordinary shanty which seemed to have been tossed by a supernatural pitchfork upon the most desolate of hills. Around him, however, were forests of pines, and of these in all their relations to cloud and sky and sun he has written many of his best poems, some of which are reproduced in the selections herewith given.

Page 14

Another Georgia poet, Sidney Lanier, wrote with added poetic passion and power of the marshes, mountains, rivers, and birds of the South. The song of the river that flowed by his birthplace is reproduced in The Song of the Chattachoochee; the robins of Tampa made melody for his weary soul and sing even now in his onomatopoetic lines. For the marshes of the Georgia coast he essayed to do what Wordsworth did for the mountains and lakes of northern England. It is a great misfortune that he did not live to complete the series of poems which he planned on the marshes of Glynn. One may take consolation for the fact, however, in the two poems which he did leave--Sunrise and The Marshes of Glynn. Both poems rank among the best interpretations of landscape in American poetry, and the latter especially, in its orchestral-like music and in its marvellous blending of forest, marsh, sky and sea, should be considered one of the masterpieces of American poetry.

In nearly every other Southern State poets have written of particular aspects of nature--notably Madison Cawein of Kentucky, Samuel Minturn Peck of Alabama, John Charles McNeill and John Henry Boner of North Carolina, and Walter Malone of Tennessee. Their poems do not show the originality of Timrod and Lanier; they are typical of the magazine poetry of the present.

Nearer to the popular mind and heart are the poems of war. It should always be remembered that it was a Southerner, Francis Scott Key, who in the dawn of a fine

Page 15

day in Chesapeake Bay, seeing the flag of his country floating upon a vessel at the time of the War of 1812, composed the lines of The Star - Spangled Banner. Theodore O'Hara wrote a dirge on the heroes of the Mexican War, which is now quoted in memory of all the brave who have died upon the field of battle. But it was the Civil War that awoke the passion of poetry in the Southern heart. When there flashed upon poetic souls, not the political issues that were at stake, but the great human situation of the struggle, they gave voice to the pent-up feelings of a new nation. James Ryder Randall, a native of Maryland, but at that time a teacher in Louisiana, could not sleep one night because he was thinking of an invading army in his native State, and in the darkness of the night he composed My Maryland. The words were at once set to music and became the inspiration of Southern soldiers. Never again did the author feel the lyrical impulse, but for a moment he caught the notes of the eternal melodies. Henry Timrod, who at the beginning of the Civil War had just begun to attract the attention of readers and critics throughout the country, was lifted to the heights of poetic inspiration by the struggle of his people. His poems, Carolina and Ethnogenesis, express the real spirit of South Carolina. After the War, when he was suffering from the pangs of poverty and disease, he wrote the Ode on the Confederate Dead--"as perfect in its tone and workmanship as though it had come out of the Greek anthology." The last stanza merits the praise that Holmes gave to Emerson's Concord Hymn: the words seem as if they had been carved

Page 16

upon marble for a thousand years. Other poets wrote at different times during the War, but of their poems only a few are of any noteworthy value. Different from the poems which served to interpret the significance of the conflict are the tributes to various soldiers who fell in the war, notably Ticknor's Little Giffen, Randall's John Pelham, and Thompson's Ashby. When the War was over, and the Southern people sat in the shadow of great disappointment and despair, Father Ryan wrote The Conquered Banner and The Sword of Robert Lee--poems which expressed in popular verse the undaunted and unbroken spirit of the South. It is easy to see the defects of his poetry, but it is also easy to understand why his lines have so sung themselves into the heart of his people.

The patriotic poetry of the South does not end, however, with the note of defeat and despair. Hayne, in his tributes to Longfellow and Whittier, struck the new note of nationalism, and Maurice Thompson interpreted the aspirations of a new era when he wrote of

"The South whose gaze is cast

No more upon the past,

But whose bright eyes the skies of promise sweep,

Whose feet in paths of progress swiftly leap;

And whose past thoughts, like cheerful rivers run,

Through odorous ways to meet the morning sun!"

But it was Sidney Lanier, who having been a brave Confederate soldier and having suffered from the strain and stress of the Reconstruction days, interpreted the new national spirit of the Southern people in his Centennial

Page 17

poem of 1876. In the very same year he wrote a much better poem, The Psalm of the West, in which he sings the triumph of freedom and nationalism. In no other American verse is there a more vivid realization of the meaning of the Republic in the larger life of the world than in the Columbus sonnets of this poem.

Of the other divisions of poems little need be said. Unfortunately, Southern poets have not made use of legends and stories to the same degree that the poets of New England have. The few given in this volume are prophetic of what may be done with this type of verse rather than suggestive of the actual achievement. Of the love poems the most significant are those of Poe and Lanier, Poe best representing the note of melancholy at the thought of the decline and passing away of a beautiful woman, and Lanier the note of aspiration and hope in the rapture of a human soul at the triumph of love. The two poets wrote out of the experience of their lives. There is no more pathetic and tragic love story in literary history than that of Poe and Virginia Clemm; and there is no more inspiring and romantic love story than that of Sidney Lanier and Mary Day. Of less poetic passion but of perhaps a finer delicacy of art are the love poems of Pinckney and of the late Father Tabb. No American Anthology would be complete without the sad and tender poems of reflection.

A distinct feature of the present volume is a collection of letters, which range all the way from the simplest statement of facts to the highest interpretations of art

Page 18

and duty. Some of them will serve as models for clear cut simple letters--a need emphasized to an increasing degree by recent books on composition and rhetoric. Some of them are interesting contemporary accounts of important historical incidents. Sidney Lanier's letters suggest in a very striking way two or three of the most significant aspects of his own genius. The most important of all are those of Robert E. Lee. This idol of the Southern people has left no other record of his mind and heart. He wrote no reminiscences nor historical accounts of the battles in which he was the chief figure. So his letters will always have an especial value. Written in clear, simple style, and in a beautiful, calm spirit, they serve as the best interpretation of his great life. The more one reads them, especially those written after the War, the more he feels that as Lee was the climax of the old South, so he was the leader and the prophet of the new South. All the forces of enlightenment that are now remaking Southern civilization should claim him as the champion of nationalism rather than sectionalism, of reason rather than passion, of fairness rather than prejudice, of progress rather than reaction, of constructive work rather than futile obstruction.

Perhaps in no other part of the world was the orator held in such high repute as in the South before the War. It has been customary to justify the lack of creative literature in that period by citing the fact that the South led the Nation in oratory. "It was the spoken word, not the printed page, that guided the thought, aroused enthusiasm, made history. These were the true universities

Page 19

of the lower South--law courts and the great religious and political gatherings--as truly as a grove was the university of Athens. The man who wished to lead or to teach must be able to speak. He could not touch the artistic sense of the people with pictures, or statues, or verse, or plays; he must charm them with voice and gesture."1

It has not been thought necessary to republish many of those orations which are so familiar already to Southern youth. Of the earlier speeches, only one each of Calhoun and Clay is here given--the one the best expression of the attitude of those who favored secession, and the other typical of those who would save the Union at any cost. Emphasis has been laid upon the orations of the leaders of a more recent era--speeches which express the spirit of progress and nationalism now so marked in Southern life. Senator Hill's speech delivered in 1871 is remarkable for its acute analysis of the defects of the old social order and for its prophecy of the new industrial era. Lamar's speech on Charles Sumner is typical of that broader spirit which would sympathetically understand the motives and ideas of the people of New England. Many can still recall the wonderful effect produced by Henry Grady's speech at the New England banquet in New York, when he so eloquently interpreted the South to the nation and the nation to the South. In it we have an epitome of the work accomplished by him in his brief and brilliant career as editor and orator. Henry Watterson's tribute to Abraham 1 The Lower South in American History, by William Garrot Brown.

Page 20

Lincoln is likewise and expression of the increasing admiration the South has for this great national hero. President Alderman's Sectionalism and Nationality is an interpretation of the significance of the great changes that have been wrought during the past generation; while Mr. Walter H. Page's The School that Built a Town is a prophecy of the marvellous future toward which the South is now so surely moving.

Page 21

I

STORIES AND ROMANCES

Page 23

THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER1

BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

Son coeur est un luth suspendu;

Sitôt qu'on le touche il résonne. BÉRANGER. 2

DURING the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher. I know not how it was--but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment, with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene before me--upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain, upon the bleak walls, upon the vacant eye-like

1 The Fall of The House of Usher was first published in the Gentleman's Magazine for September, 1839. Poe's name in literature does not rest upon this story, but it constitutes one of his characteristic descriptions of the unreal, ghostly, and supernatural world, in which department he made for himself an enduring fame. 2 "His heart is a suspended lute; as soon as it is touched it resounds."--J. P. de Béranger (1780-1857), a popular French lyric poet.

Page 24

windows, upon a few rank sedges, and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees--with an utter depression of soul, which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opium; the bitter lapse into everyday life, the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart--an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime. What was it--I paused to think--what was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher? It was a mystery all insoluble; nor could I grapple with the shadowy fancies that crowded upon me as I pondered. I was forced to fall back upon the unsatisfactory conclusion, that while, beyond doubt, there are combinations of very simple natural objects which have the power of thus affecting us, still the analysis of this power lies among considerations beyond our depth. It was possible, I reflected, that a mere different arrangement of the particulars of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps to annihilate, its capacity for sorrowful impression; and acting upon this idea, I reined my horse to the precipitous brink of a black and lurid tarn1 that lay in unruffled lustre by the dwelling, and gazed down--but with a shudder even more thrilling than before--upon the remodelled and inverted images of the gray sedge, and the ghastly tree stems, and the vacant and eye-like windows.

Nevertheless, in this mansion of gloom I now proposed to myself a sojourn of some weeks. Its proprietor, Roderick Usher, had been one of my boon

1 A small mountain lake.

Page 25

companions in boyhood; but many years had elapsed since our last meeting. A letter, however, had lately reached me in a distant part of the country--a letter from him--which in its wildly importunate nature had admitted of no other than a personal reply. The MS. gave evidence of nervous agitation. The writer spoke of acute bodily illness, of a mental disorder which oppressed him, and of an earnest desire to see me, as his best, and indeed his only personal friend, with a view of attempting, by the cheerfulness of my society, some alleviation of his malady. It was the manner in which all this, and much more, was said--it was the apparent heart that went with his request--which allowed me no room for hesitation; and I accordingly obeyed forthwith what I still considered a very singular summons.

Although as boys we had been even intimate associates, yet I really knew little of my friend. His reserve had been always excessive and habitual. I was aware, however, that his very ancient family had been noted, time out of mind, for a peculiar sensibility of temperament, displaying itself, through long ages, in many works of exalted art, and manifested of late in repeated deeds of, munificent yet unobtrusive charity, as well as in a passionate devotion to the intricacies, perhaps even more than to the orthodox and easily recognizable beauties, of musical science. I had learned, too, the very remarkable fact that the stem of the Usher race, all time-honored as it was, had put forth at no period any enduring branch; in other words, that the entire family lay in the direct line of descent, and had always, with very trifling and very temporary variation, so lain. It was this deficiency, I considered,

Page 26

while running over in thought the perfect keeping of the character of the premises with the accredited character of the people, and while speculating upon the possible influence which the one, in the long lapse of centuries, might have exercised upon the other--it was this deficiency, perhaps, of collateral issue, and the consequent undeviating transmission from sire to son of the patrimony with the name, which had, at length, so identified the two as to merge the original title of the estate in the quaint and equivocal appellation of the "House of Usher"--an appellation which seemed to include, in the minds of the peasantry who used it, both the family and the family mansion.

I have said that the sole effect of my somewhat childish experiment--that of looking down within the tarn--had been to deepen the first singular impression. There can be no doubt that the consciousness of the rapid increase of my superstition--for why should I not so term it?--served mainly to accelerate the increase itself. Such, I have long known, is the paradoxical law of all sentiments having terror as a basis. And it might have been for this reason only, that, when I again uplifted my eyes to the house itself, from its image in the pool, there grew in my mind a strange fancy--a fancy so ridiculous, indeed, that I but mention it to show the vivid force of the sensations which oppressed me. I had so worked upon my imagination as really to believe that about the whole mansion and domain there hung an atmosphere peculiar to themselves and their immediate vicinity--an atmosphere which had no affinity with the air of heaven, but which had reeked up from the decayed trees, and the gray wall, and the silent tarn--

Page 27

a pestilent and mystic vapor, dull, sluggish, faintly discernible, and leaden-hued.

Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building. Its principal feature seemed to be that of an excessive antiquity. The discoloration of ages had been great. Minute fungi overspread the whole exterior, hanging in a fine tangled web-work from the eaves. Yet all this was apart from any extraordinary dilapidation. No portion of the masonry had fallen; and there appeared to be a wild inconsistency between its still perfect adaptation of parts and the crumbling condition of the individual stones. In this there was much that reminded me of the specious totality of old wood-work which has rotted for long years in some neglected vault, with no disturbance from the breath of the external air. Beyond this indication of extensive decay, however, the fabric gave little token of instability. Perhaps the eye of a scrutinizing observer might have discovered a barely perceptible fissure, which, extending from the roof of the building in front, made its way down the wall in a zig-zag direction, until it became lost in the sullen waters of the tarn.

Noticing these things, I rode over a short cause-way to the house. A servant in waiting took my horse, and I entered the Gothic archway of the hall. A valet, of stealthy step, thence conducted me, in silence, through many dark and intricate passages in my progress to the studio of his master. Much that I encountered on the way contributed, I know not how, to heighten the vague sentiments of which I have already spoken. While the objects around me--while the carvings of the ceilings, the sombre

Page 28

tapestries of the walls, the ebon blackness of the floors, and the phantasmagoric armorial trophies which rattled as I strode, were but matters to which, or to such as which, I had been accustomed from my infancy--while I hesitated not to acknowledge how familiar was all this--I still wondered to find how unfamiliar were the fancies which ordinary images were stirring up. On one of the staircases, I met the physician of the family. His countenance, I thought, wore a mingled expression of low cunning and perplexity. He accosted me with trepidation and passed on. The valet now threw open a door and ushered me into the presence of his master.

The room in which I found myself was very large and lofty. The windows were long, narrow, and pointed, and at so vast a distance from the black oaken floor as to be altogether inaccessible from within. Feeble gleams of encrimsoned light made their way through the trellised panes, and served to render sufficiently distinct the more prominent objects around; the eye, however, struggled in vain to reach the remoter angles of the chamber, or the recesses of the vaulted and fretted ceiling. Dark draperies hung upon the walls. The general furniture was profuse, comfortless, antique, and tattered. Many books and musical instruments lay scattered about, but failed to give any vitality to the scene. I felt that I breathed an atmosphere of sorrow. An air of stern, deep, and irredeemable gloom hung over and pervaded all.

Upon my entrance, Usher arose from a sofa on which he had been lying at full length, and greeted me with a vivacious warmth which had much in it, I at first thought, of an overdone cordiality--of the constrained effort of the ennuyé man of the world.

Page 29

A glance, however, at his countenance, convinced me of his perfect sincerity. We sat down; and for some moments, while he spoke not, I gazed upon him with a feeling half of pity, half of awe. Surely man had never before so terribly altered, in so brief a period, as had Roderick Usher! It was with difficulty that I could bring myself to admit the identity of the wan being before me with the companion of my early boyhood. Yet the character of his face had been at all times remarkable. A cadaverousness of complexion; an eye large, liquid, and luminous beyond comparison; lips somewhat thin and very pallid, but of a surpassingly beautiful curve; a nose of delicate Hebrew model,1 but with a breadth of nostril unusual in similar formations; a finely moulded chin, speaking, in its want of prominence, of a want of moral energy; hair of a more than web-like softness and tenuity; these features, with an inordinate expansion above the regions of the temple, made up altogether a countenance not easily to be forgotten. And now in the mere exaggeration of the prevailing character of these features, and of the expression they were wont to convey, lay so much of change that I doubted to whom I spoke. The now ghastly pallor of the skin, and the now miraculous lustre of the eye, above all things startled and even awed me. The silken hair, too, had been suffered to grow all unheeded, and as, in its wild gossamer texture, it floated rather than fell about the face, I could not, even with effort, connect its arabesque expression with any idea of simple humanity.

1 In his Ligeia Poe has this sentence: "I looked at the delicate outlines of the nose, and nowhere but in the graceful medallions of the Hebrews had I beheld a similar perfection."

Page 30

In the manner of my friend I was at once struck with an incoherence--an inconsistency; and I soon found this to arise from a series of feeble and futile struggles to overcome an habitual trepidancy--an excessive nervous agitation. For something of this nature I had indeed been prepared, no less by his letter than by reminiscences of certain boyish traits, and by conclusions deduced from his peculiar physical conformation and temperament. His action was alternately vivacious and sullen. His voice varied rapidly from a tremulous indecision (when the animal spirits seemed utterly in abeyance) to that species of energetic concision--that abrupt, weighty, unhurried, and hollow-sounding enunciation--that leaden, self-balanced, and perfectly modulated guttural utterance, which may be observed in the lost drunkard, or the irreclaimable eater of opium, during the periods of his most intense excitement.

It was thus that he spoke of the object of my visit, of his earnest desire to see me, and of the solace he expected me to afford him. He entered, at some length, into what he conceived to be the nature of his malady. It was, he said, a constitutional and a family evil, and one for which he despaired to find a remedy--a mere nervous affection, he immediately added, which would undoubtedly soon pass off. It displayed itself in a host of unnatural sensations. Some of these, as he detailed them, interested and bewildered me; although, perhaps, the terms and the general manner of the narration had their weight. He suffered much from a morbid acuteness of the senses; the most insipid food was alone endurable; he could wear only garments of certain texture; the odors of all flowers were oppressive; his eyes were

Page 31

tortured by even a faint light; and there were but peculiar sounds, and these from stringed instruments, which did not inspire him with horror.

To an anomalous species of terror I found him a bounden slave. "I shall perish," said he, "I must perish in this deplorable folly. Thus, thus, and not otherwise, shall I be lost. I dread the events of the future, not in themselves, but in their results. I shudder at the thought of any, even the most trivial, incident, which may operate upon this intolerable agitation of soul. I have, indeed, no abhorrence of danger, except in its absolute effect--in terror. In this unnerved--in this pitiable condition--I feel that the period will sooner or later arrive when I must abandon life and reason together, in some struggle with the grim phantasm, FEAR."

I learned, moreover, at intervals, and through broken and equivocal hints, another singular feature of his mental condition. He was enchained by certain superstitious impressions in regard to the dwelling which he tenanted, and whence, for many years, he had never ventured forth--in regard to an influence whose supposititious force was conveyed in terms too shadowy here to be restated--an influence which some peculiarities in the mere form and substance of his family mansion had, by dint of long sufferance, he said, obtained over his spirit--an effect which the physique of the gray walls and turrets, and of the dim tarn into which they all looked down, had, at length, brought about upon the morale1 of his existence.

He admitted, however, although with hesitation, that much of the peculiar gloom which thus afflicted

1 Mental state: spirit.

Page 32

him could be traced to a more natural and far more palpable origin--to the severe and long-continued illness--indeed to the evidently approaching dissolution, of a tenderly beloved sister--his sole companion for long years--his last and only relative on earth. "Her decease," he said, with a bitterness which I can never forget, "would leave him (him the hopeless and the frail) the last of the ancient race of the Ushers." While he spoke, the lady Madeline (for so was she called) passed slowly through a remote portion of the apartment, and, without having noticed my presence, disappeared. I regarded her with an utter astonishment not unmingled with dread--and yet I found it impossible to account for such feelings. A sensation of stupor oppressed me, as my eyes followed her retreating steps. When a door, at length, closed upon her, my glance sought instinctively and eagerly the countenance of the brother--but he had buried his face in his hands, and I could only perceive that a far more than ordinary wanness had overspread the emaciated fingers through which trickled many passionate tears.

The disease of the lady Madeline had long baffled the skill of her physicians. A settled apathy, a gradual wasting away of the person, and frequent although transient affections of a partially cataleptical character, were the unusual diagnosis. Hitherto she had steadily borne up against the pressure of her malady, and had not betaken herself finally to bed; but, on the closing in of the evening of my arrival at the house, she succumbed (as her brother told me at night with inexpressible agitation) to the prostrating power of the destroyer; and I learned that the glimpse I had obtained of her person would thus probably be the

Page 33

last I should obtain--that the lady, at least while living, would be seen by me no more.

For several days ensuing, her name was unmentioned by either Usher or myself; and during this period I was busied in earnest endeavors to alleviate the melancholy of my friend. We painted and read together; or I listened, as if in a dream, to the wild improvisations of his speaking guitar. And thus, as a closer and still closer intimacy admitted me more unreservedly into the recesses of his spirit, the more bitterly did I perceive the futility of all attempt at cheering a mind from which darkness, as if an inherent positive quality, poured forth upon all objects of the moral and physical universe, in one unceasing radiation of gloom.

I shall ever bear about me a memory of the many solemn hours I thus spent alone with the master of the House of Usher. Yet I should fail in any attempt to convey an idea of the exact character of the studies, or of the occupations, in which he involved me, or led me the way. An excited and highly distempered ideality threw a sulphureous lustre over all. His long improvised dirges will ring forever in my ears. Among other things, I hold painfully in mind a certain singular perversion and amplification of the wild air of the last waltz of Von Weber.1 From the paintings over which his elaborate fancy brooded, and which grew, touch by touch, into vaguenesses at which I shuddered the more thrillingly, because I shuddered knowing not why;-from these paintings (vivid as their images now are before me) I would in vain endeavor to educe more than a small portion

1 Karl Maria, Baron von Weber (1786-1826), a celebrated German musician.

Page 34

which should lie within the compass of merely written words. By the utter simplicity, by the nakedness of his designs, he arrested and overawed attention. If ever mortal painted an idea, that mortal was Roderick Usher. For me at least, in the circumstances then surrounding me, there arose, out of the pure abstractions which the hypochondriac contrived to throw upon his canvas, an intensity of intolerable awe, no shadow of which felt I ever yet in the contemplation of the certainly glowing yet too concrete reveries of Fuseli.1

One of the phantasmagoric conceptions of my friend, partaking not so rigidly of the spirit of abstraction, may be shadowed forth, although feebly, in words. A small picture presented the interior of an immensely long and rectangular vault or tunnel, with low walls, smooth, white, and without interruption or device. Certain accessory points of the design served well to convey the idea that this excavation lay at an exceeding depth below the surface of the earth. No outlet was observed in any portion of its vast extent, and no torch or other artificial source of light was discernible; yet a flood of intense rays rolled throughout, and bathed the whole in a ghastly and inappropriate splendor.

I have just spoken of that morbid condition of the auditory nerve which rendered all music intolerable to the sufferer, with the exception of certain effects of stringed instruments. It was, perhaps, the narrow limits to which he thus confined himself upon the guitar, which gave birth, in great measure, to the fantastic character of his performances. But the fervid facility of his impromptus could not be so accounted for. They must have been, and were, in the

1 Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), born in Zurich, a famous artist.

Page 35

notes, as well as in the words of his wild fantasias (for he not unfrequently accompanied himself with rhymed verbal improvisations), the result of that intense mental collectedness and concentration to which I have previously alluded as observable only in particular moments of the highest artificial excitement. The words of one of these rhapsodies I have easily remembered. I was, perhaps, the more forcibly impressed with it, as he gave it, because, in the under or mystic current of its meaning, I fancied that I perceived, and for the first time, a full consciousness, on the part of Usher, of the tottering of his lofty reason upon her throne. The verses, which were entitled "The Haunted Palace," ran very nearly, if not accurately, thus:--

I

"In the greenest of our valleys

By good angels tenanted,

Once a fair and stately palace--

Radiant palace--reared its head.

In the monarch Thought's dominion,

It stood there;

Never seraph spread a pinion

Over fabric half so fair.

II

"Banners yellow, glorious, golden,

On its roof did float and flow,

(This--all this--was in the olden

Time long ago)

And every gentle air that dallied,

In that sweet day,

Along the ramparts plumed and pallid,

A wingèd odor went away.

Page 36

III

"Wanderers in that happy valley

Through two luminous windows saw

Spirits moving musically

To a lute's well-tunèd law,

Round about a throne where, sitting,

Porphyrogene,1

In state his glory well befitting,

The ruler of the realm was seen.

IV

"And all with pearl and ruby glowing

Was the fair palace door,

Through which came flowing, flowing, flowing,

And sparkling evermore,

A troop of Echoes whose sweet duty

Was but to sing,

In voices of surpassing beauty,

The wit and wisdom of their king.

V

"But evil things, in robes of sorrow,

Assailed the monarch's high estate;

(Ah, let us mourn, for never morrow

Shall dawn upon him, desolate!)

And round about his home the glory

That blushed and bloomed

Is but a dim-remembered story

Of the old time entombed.

VI

"And travellers now within that valley

Through the red-litten2 windows see

Vast forms that move fantastically

To a discordant melody;

Page 37

1 Of royal birth. 2 Old participial form of the verb light.

While, like a ghastly rapid river,

Through the pale door

A hideous throng rush out forever,

And laugh--but smile no more."

I well remember that suggestions arising from this ballad led us into a train of thought, wherein there became manifest an opinion of Usher's which I mention not so much on account of its novelty, (for other men1 have thought thus,) as on account of the pertinacity with which he maintained it. This opinion, in its general form, was that of the sentience2 of all vegetable things. But in his disordered fancy the idea had assumed a more daring character, and trespassed, under certain conditions, upon the kingdom of inorganization.3 I lack words to express the full extent, or the earnest abandon, of his persuasion. The belief, however, was connected (as I have previously hinted) with the gray stones of the home of his forefathers. The conditions of the sentience had been here, he imagined, fulfilled in the method of collocation of these stones--in the order of their arrangement, as well as in that of the many fungi which over-spread them, and of the decayed trees which stood around--above all, in the long undisturbed endurance of this arrangement, and in its reduplication in the still waters of the tarn. Its evidence--the evidence of the sentience--was to be seen, he said (and I here started as he spoke), in the gradual yet certain condensation of an atmosphere of their own about the waters and the walls. The result was discoverable,

1 Watson, Dr. Percival, Spallanzani, and especially the Bishop of Landaff. See Chemical Essays, vol. v. 2 Possession of mental life. 3 That is, the mineral kingdom.

Page 38

he added, in that silent, yet importunate and terrible influence which for centuries had moulded the destinies of his family, and which made him what I now saw him--what he was. Such opinions need no comment, and I will make none.

Our books--the books which, for years, had formed no small portion of the mental existence of the invalid--were, as might be supposed, in strict keeping with this character of phantasm. We pored together over such works as the Ververt et Chartreuse of Gresset1; the Belphegor of Machiavelli;2 the Heaven and Hell of Swedenborg;3 the Subterranean Voyage of Nicholas Klimm by Holberg;4 the Chiromancy of Robert Flud,5 of Jean D'Indaginé,6 and of De la Chambre; the Journey into the Blue Distance of Tieck;7 and the City of the Sun of Campanella.8 One favorite volume was a small octavo edition of the Directorium Inquisitorum, by the Dominican Eymeric de Gironne;9 and there were passages in Pomponius Mela,10 about the old African Satyrs and

1 Jean Baptiste Gresset (1709-1777), a French poet and dramatist. 2 Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), a Florentine statesman and political writer. 3 Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), a Swedish theologian and naturalist. 4 Ludwig von Holberg (1684-1754), a Danish poet and dramatist. 5 Robert Flud (1574-1637), an English physician and philosopher. 6 Jean D'Indaginé and De la Chambre, European writers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries respectively. 7 Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853), a German romanticist. 8 Tomaso Campanella (1568-1639), an Italian philosopher. 9 Nicholas Eymeric (1320-1399), a judge of the heretics in the Spanish Inquisition. 10 Pomponius Mela, a Spanish geographer.

Page 39

Ægipans,1 over which Usher would sit dreaming for hours.His chief delight, however, was found in the perusal of an exceedingly rare and curious book in quarto Gothic--the manual of a forgotten church--the Vigilioe Mortuorum secundum Chorum Ecclesioe Maguntinoe.2

I could not help thinking of the wild ritual of this work, and of its probable influence upon the hypochondriac, when one evening, having informed me abruptly that the lady Madeline was no more, he stated his intention of preserving her corpse for a fortnight (previously to its final interment), in one of the numerous vaults within the main walls of the building. The worldly reason, however, assigned for this singular proceeding, was one which I did not feel at liberty to dispute. The brother had been led to his resolution (so he told me) by consideration of the unusual character of the malady of the deceased, of certain obtrusive and eager inquiries on the part of her medical men, and of the remote and exposed situation of the burial-ground of the family. I will not deny that when I called to mind the sinister countenance of the person whom I met upon the staircase, on the day of my arrival at the house, I had no desire to oppose what I regarded as at best but a harmless, and by no means an unnatural, precaution.

At the request of Usher, I personally aided him in the arrangements for the temporary entombment. The body having been encoffined, we two alone bore it to its rest. The vault in which we placed it (and

1 Ægipans, the god Pan. 2 "Night Watches of the Dead like unto the Choir of the Church of Maguntina."

Page 40

which had been so long unopened that our torches, half smothered in its oppressive atmosphere, gave us little opportunity for investigation) was small, damp, and entirely without means of admission for light; lying, at great depth, immediately beneath that portion of the building in which was my own sleeping apartment. It had been used, apparently, in remote feudal times, for the worst purposes of a donjon1-keep, and in later days as a place of deposit for powder, or some other highly combustible substance, as a portion of its floor, and the whole interior of a long archway through which we reached it, were carefully sheathed with copper. The door, of massive iron, had been, also, similarly protected. Its immense weight caused an unusually sharp grating sound, as it moved upon its hinges.

Having deposited our mournful burden upon tressels within this region of horror, we partially turned aside the yet unscrewed lid of the coffin, and looked upon the face of the tenant. A striking similitude between the brother and sister now first arrested my attention; and Usher, divining, perhaps, my thoughts, murmured out some few words from which I learned that the deceased and himself had been twins, and that sympathies of a scarcely intelligible nature had always existed between them. Our glances, however, rested not long upon the dead--for we could not regard her unawed. The disease which had thus entombed the lady in the maturity of youth, had left, as usual in all maladies of a strictly cataleptical character, the mockery of a faint blush upon the bosom and the face, and that suspiciously lingering smile upon the lip which is so terrible in death. We replaced

1 Dungeon.

Page 41

and screwed down the lid, and, having secured the door of iron, made our way, with toil, into the scarcely less gloomy apartments of the upper portion of the house.

And now, some days of bitter grief having elapsed, an observable change came over the features of the mental disorder of my friend. His ordinary manner had vanished. His ordinary occupations were neglected or forgotten. He roamed from chamber to chamber with hurried, unequal, and objectless step. The pallor of his countenance had assumed, if possible, a more ghastly hue--but the luminousness of his eye had utterly gone out. The once occasional huskiness of his tone was heard no more; and a tremulous quaver, as if of extreme terror, habitually characterized his utterance. There were times, indeed, when I thought his unceasingly agitated mind was laboring with some oppressive secret, to divulge which he struggled for the necessary courage. At times, again, I was obliged to resolve all into the mere inexplicable vagaries of madness, for I beheld him gazing upon vacancy for long hours, in an attitude of the profoundest attention, as if listening to some imaginary sound. It was no wonder that his condition terrified--that it infected me. I felt creeping upon me, by slow yet certain degrees, the wild influences of his own fantastic yet impressive superstitions.

It was, especially, upon retiring to bed late in the night of the seventh or eighth day after the placing of the lady Madeline within the donjon, that I experienced the full power of such feelings. Sleep came not near my couch--while the hours waned and waned away. I struggled to reason off the nervousness which had dominion over me. I endeavored to believe that much, if not all, of what I felt was due

Page 42

to the bewildering influence of the gloomy furniture of the room--of the dark and tattered draperies which, tortured into motion by the breath of a rising tempest, swayed fitfully to and fro upon the walls, and rustled uneasily about the decoration of the bed. But my efforts were fruitless. An irrepressible tremor gradually pervaded my frame; and at length there sat upon my very heart an incubus of utterly causeless alarm. Shaking this off with a gasp and a struggle, I uplifted myself upon the pillows, and, peering earnestly within the intense darkness of the chamber, hearkened--I know not why, except that an instinctive spirit prompted me--to certain low and indefinite sounds which came through the pauses of the storm, at long intervals, I know not whence. Overpowered by an intense sentiment of horror, unaccountable yet unendurable, I threw on my clothes with haste (for I felt that I should sleep no more during the night), and endeavored to arouse myself from the pitiable condition into which I had fallen, by pacing rapidly to and fro through the apartment.

I had taken but few turns in this manner, when a light step on an adjoining staircase arrested my attention. I presently recognized it as that of Usher. In an instant afterward he rapped with a gentle touch at my door, and entered, bearing a lamp. His countenance was, as usual, cadaverously wan--but, moreover, there was a species of mad hilarity in his eyes--an evidently restrained hysteria in his whole demeanor. His air appalled me--but anything was preferable to the solitude which I had so long endured, and I even welcomed his presence as a relief.

"And you have not seen it?" he said abruptly, after having stared about him for some moments in

Page 43

silence--"you have not then seen it?--but, stay! you shall." Thus speaking, and having carefully shaded his lamp, he hurried to one of the casements, and threw it freely open to the storm.

The impetuous fury of the entering gust nearly lifted us from our feet. It was, indeed, a tempestuous yet sternly beautiful night, and one wildly singular in its terror and its beauty. A whirlwind had apparently collected its force in our vicinity; for there were frequent and violent alterations in the direction of the wind; and the exceeding density of the clouds (which hung so low as to press upon the turrets of the house) did not prevent our perceiving the lifelike velocity with which they flew careering from all points against each other, without passing away into the distance. I say that even their exceeding density did not prevent our perceiving this; yet we had no glimpse of the moon or stars, nor was there any flashing forth of the lightning. But the under surfaces of the huge masses of agitated vapor, as well as all terrestrial objects immediately around us, were glowing in the unnatural light of a faintly luminous and distinctly visible gaseous exhalation which hung about and enshrouded the mansion.

"You must not--you shall not behold this!" said I, shudderingly, to Usher, as I led him with a gentle violence from the window to a seat. "These appearances, which bewilder you, are merely electrical phenomena not uncommon--or it may be that they have their ghastly origin in the rank miasma of the tarn. Let us close this casement; the air is chilling and dangerous to your frame. Here is one of your favorite romances. I will read, and you shall listen;--and so we will pass away this terrible night together."

Page 44

The antique volume which I had taken up was the "Mad Trist"1 of Sir Launcelot Canning; but I had called it a favorite of Usher's more in sad jest than in earnest; for, in truth, there is little in its uncouth and unimaginative prolixity which could have had interest for the lofty and spiritual ideality of my friend. It was, however, the only book immediately at hand; and I indulged a vague hope that the excitement which now agitated the hypochondriac might find relief (for history of mental disorder is full of similar anomalies) even in the extremeness of the folly which I should read. Could I have judged, indeed, by the wild overstrained air of vivacity with which he hearkened, or apparently hearkened, to the words of the tale, I might well have congratulated myself upon the success of my design.

I had arrived at that well-known portion of the story where Ethelred, the hero of the Trist, having sought in vain for peaceable admission into the dwelling of the hermit, proceeds to make good an entrance by force. Here, it will be remembered, the words of the narrative run thus:

"And Ethelred, who was by nature of a doughty heart, and who was now mighty withal, on account of the powerfulness of the wine which he had drunken, waited no longer to hold parley with the hermit, who, in sooth, was of an obstinate and maliceful turn, but, feeling the rain upon his shoulders, and fearing the rising of the tempest, uplifted his mace outright, and with blows made quickly room in the plankings of the door for his gauntleted hand; and now pulling therewith sturdily, he so cracked, and ripped, and tore all asunder, that the noise of the dry and hollow-sounding wood alarumed and reverberated throughout the forest."

1 Both the title and the extracts are probably invented by Poe.

Page 45

At the termination of this sentence I started, and for a moment paused; for it appeared to me (although I at once concluded that my excited fancy had deceived me)--it appeared to me that from some very remote portion of the mansion there came, indistinctly, to my ears, what might have been, in its exact similarity of character, the echo (but a stifled and dull one certainly) of the very cracking and ripping sound which Sir Launcelot had so particularly described. It was, beyond doubt, the coincidence alone which had arrested my attention; for, amid the rattling of the sashes of the casements, and the ordinary commingled noises of the still increasing storm, the sound, in itself, had nothing, surely, which should have interested or disturbed me. I continued the story:

"But the good champion Ethelred, now entering within the door, was sore enraged and amazed to perceive no signal of the maliceful hermit; but, in the stead thereof, a dragon of a scaly and prodigious demeanor, and of a fiery tongue, which sate in guard before a palace of gold, with a floor of silver; and upon the wall there hung a shield of shining brass with this legend enwritten--

Who entereth herein a conqueror hath bin;

Who slayeth the dragon, the shield he shall win.

And Ethelred uplifted his mace, and struck upon the head of the dragon, which fell before him, and gave up his pesty breath, with a shriek so horried and harsh, and withal so piercing, that Ethelred had fain1 to close his ears with his hands against the dreadful noise of it, the like whereof was never before heard."

Here again I paused abruptly, and now with a feeling of wild amazement; for there could be no

1 Wished (obsolete).

Page 46