Fifty Years Since: An Address Before the Alumni Association of the University of North Carolina. From The North Carolina University Magazine 9, no. 10 (June 1860): 577-611:

Electronic Edition.

Hooper, William, 1792-1876

Funding from the State Library of North Carolina supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Brian Dietz

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Brian Dietz, and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2005

ca. 115K

University Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2005.

Source Description:

(caption title) Fifty Years Since: An Address Before the Alumni Association of the University of North Carolina

(journal title) North Carolina University Magazine

William Hooper, D. D. LL. D.

William J. Headen, et al.

35 p.

Raleigh, N.C.

The Office of the "Weekly Post"

June 1860

From The North Carolina University Magazine 9, no. 10 (June 1860): 577-611

Call number C378 UQm v.9 c.4 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-Chapel Hill digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Latin

- Greek

LC Subject Headings:

- University of North Carolina (1793-1962) -- Alumni and alumnae.

- University of North Carolina (1793-1962) -- Anecdotes.

- University of North Carolina (1793-1962) -- History.

Revision History:

- 2005-08-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2005-05-10,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2004-11-22,

Brian Dietz

finished TEI/SGML encoding.

- 2004-10-29,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

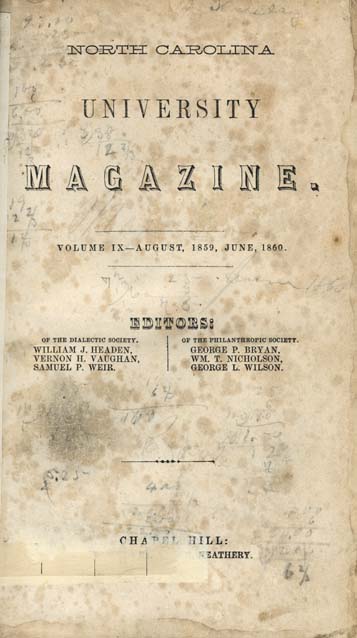

[Title Page Image]

NORTH CAROLINA

UNIVERSITY

MAGAZINE.

VOLUME IX--AUGUST, 1859, JUNE, 1860.

| EDITORS: | |

| OF THE DIALECTIC SOCIETY. | OF THE PHILANTHROPIC SOCIETY. |

| WILLIAMM. J. HEADEN, | GEORGE P. BRYAN, |

| VERNON H. VAUGHAN, | WM. T. NICHOLSON, |

| SAMUEL P. WEIR. | GEORGE L. WILSON. |

CHAPEL HILL:

PRINTED BY JOHN B. NEATHERY.

1860.

Page 577

NORTH CAROLINA

UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE

| EDITORS: | |

| OF THE DIALECTIC SOCIETY. | OF THE PHILANTHROPIC SOCIETY. |

| WILLIAM. J. HEADEN, | GEORGE P. BRYAN, |

| VERNON H. VAUGHAN, | WM. T. NICHOLSON, |

| SAMUEL P. WEIR. | GEORGE L. WILSON. |

| Vol. 9. | JUNE, 1860 | No. 2. |

FIFTY YEARS SINCE:

AN ADDRESS BEFORE THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA,

BY

WILLIAM HOOPER, D. D. LL. D.,

June 1st, I859.

BROTHERS OF THE ALUMNI--

LITERARY CHILDREN OF ONE ALMA MATER:

WE come together at this annual festival, to salute and congratulate each other--to look back on the past and compare it with the present--to gratify an honest pride in contrasting the feeble and sickly infancy of our literary mother with her present vigorous maturity, and to breathe a common filial prayer that that vigorous maturity may long flourish, and not soon be succeeded by a languishing old age.

Two years ago, I delivered, at another College, what I expected would be my final offering at the shrine of the muses; but since the committee, representing the public opinion, have not consented to give me a discharge from this mode of paying a debt of filial gratitude, I submit to their dictation, being glad to receive, in such appointment, their flattering attestation that they yet detect no mark of senility disqualifying me for appearing before a commencement audience, and especially the audience of 1859, so highly honored by the presence of the chief magistrate of the republic. I am proud to find, from two astronomical observations, that Chapel Hill lies right in the orbit of Jupiter and his satellites, and that the period of his revolution is about twelve years. I beg the professor of astronomy here to make this entry in his Ephemeris, and to look out for the recurrence of the same phenomenon about 1871; if indeed, at that time, the head of this great republic be fitly symbolized by that glorious planet, and be not shivered, ere that cycle rolls around, by some

Page 578

disastrous concussion, into a score of nameless asteroids. May heaven avert the omen! Had I said this at the city of Washington, and were I some quarter of a century younger, his Excellency might consider this exordium as the prelude to some application for office; but on an academical jubilee like this, and from a speaker bordering on three-score and seven, he will receive it, I trust, only as the cordial and sincere expression of that rejoicing which we all feel at the honor of this visit. Yes, a truce from office-seeking here at least. We are glad to find that the President has survived that period of vexatious importunity--that crown of thorns which every President is obliged to wear on his first accession--and that he is likely, from present appearances, to serve his country for many years to come.

I believe it is expected of the speaker to the Alumni that he shall entertain them with reminiscences of persons and things long gone by--the longer the better. Hence the selection, for this year, of your humble servant, there being very few now surviving who can number half a century from their graduation. And although I am neither a bachelor nor a widower, and therefore have no interest in making myself out younger than I am with my fair auditors, yet I will merely hint to this benevolent assembly that although it is just fifty years since I got my sheepskin, I was then in my prætexta, and had not yet put on the toga virilis. I shall, however, be happy if I get through the task of this day without extorting from some of my hearers the exclamation of the Roman satirist: "The old steed is broken down; take him from the turf before he disgraces himself."*

*

Solve senescentem mature sanus equum ne

Peccet ad extremum, ridendus.--HOR.

Particularly might my friends be anxious about me now as having to perform my part of the duties of this occasion after the display of this morning. I assure them that I feel a great degree of tranquility in that very consideration which they might deem a just cause of agitation and disquietude, to-wit: That I am succeeding the orator of the day. "I am no orator as Brutus is." Upon him I roll the responsibility of supplying all the eloquence due to the day. His shoulders are well able to bear the burden; while to me remains only the easier part of the master of ceremonies, to announce to the audience--"Ladies and gentlemen, the concert is over."*

* This paragraph was added after hearing the splendid speech of Mr. McRae in the forenoon.

When I look back through the vista of those fifty years and bring before my "mind's eye" the long train of alumni who have risen to eminence and adorn their country, both at home and abroad, I may be indulged

Page 579

in something of a spirit of glorying, if as a professor of the University, I have had any share in the formation of these ornaments of the republic. I confess, when I look over the catalogue of graduates, and see so many laureled heads into which it was my lot to pack a portion of useful knowledge, I am elated with a little of that pride which swelled the breast of the mother of the gods on Mount Olympus, as she looked at her children around her:

See all her progeny, illustrious sight!

Behold and count them, as they rise to light;

She sees around her in the blest abode,

A hundred sons, and every son a god!

I have said that it is perhaps expected of the alumni address, that it shall entertain you with reminiscences; and I hope I shall not be too severely judged, if in preparing this entertainment, I looked forward to a hot day, a crowded house, and a great deal of grave business--all which anticipations warranted me in the selection of reminiscences of an amusing, as well as of an instructive kind. Indeed, a retrospect of Chapel Hill antiquities, so far back as half-a-century, must needs bring up many a scene of so comic a nature,

That to be grave, exceeds all power of face,

In telling or in hearing of the case.

The first of the Waverly novels was entitled "Sixty Years Since," which serves as a date to the origin of those wonderful compositions. My tale shall be entitled "Fifty Years Since," though some of my story will embrace incidents within forty years of the present date; and if it fall (as of course it will) infinitely below that of the renowned Sir Walter, in all other respects, it will rise above him in one; that, whereas most of his is fiction, mine is sober fact. At least, I intend it to be so. But it may be with me as it was with Boswell in his celebrated "Life of Dr. Johnson." He tells us that it was his habit, after being in company with his hero, to go immediately to his lodgings and record the sayings and doings of the Doctor, at once, while they were fresh in his memory; but that sometimes, when circumstances interfered, the facts lay on his memory for a day or two, and that he thought they were the better of it--as they had a chance to grow mellow!

I hope that if any of my co-evals are present, who can look back as far into our antiquities as myself, they will not have occasion to say, when they hear some of my recitals: "There is a fact that has grown mellow in his memory," or to compare me with the aged harper in Scott's Lay of the Last Minstrel:

"Each blank in faithless memory void,

The poet's glowing thought supplied."

It is my part then, to-day, to go back to the very increnabula of our college--the cradle of its infancy, and to call up recollections of some

Page 580

who rocked that cradle. And I dare say while I am telling the story of the poor and beggarly minority of our alma mater, some of her proud, saucy sons of the present generation will smile scornfully at the humility of our origin. When I tell them that the classes of President Polk,--of Governors Branch, Brown, Manly, Morehead, Mosely, Spaight--of Judges Murphey, Cameron, Martin, Donnel, Williams, Mason, Anderson; of Senators Mangum and Haywood--of Drs. Hawks, Morrison, Green, and of many other graduates forty years back, eminent for merit though not holding office--when I tell the proud collegians of the present day, that these men came out of classes consisting of nine, ten, fourteen, fifteen, the largest twenty one,--they will set up a broad laugh, and think how poor a figure a class of ten or fifteen must cut on a commencement day; and one will say; "Why I graduated with seventy five," and another: "I with one hundred," and another: "I with a hundred and ten." Well, I know of no better way to shelter myself from the storm of your ridicule, than by telling you a story. "Once upon a time," says Æsop, "a fox brought out her whole brood of little foxes, and paraded them before the lioness, and said: 'Look here! see what a family I have, whereas you have but one!''I know said the queen of beasts that I bear but one at a time, but then he is a lion!'" I would also remind you, young classics, of the story of Niobe who boasted of her twelve children, and crowed over Latona, who had only two; but then Latona's children were the sun and moon! Forgive, youug gentlemen, these boastings of an old man. You know it is the characteristic of such a one, to overrate the past, and underrate the present. But I trust I am sufficiently sensible of the vast advances made in all things at Chapel Hill since my day, to do full justice to the present age. You have turned the wild into a garden. You have substituted for the meagre bill of fare with which our minds were obliged to content themselves, a table rich in all the stores of learning which a half-century of unexampled progress has heaped upon it. I hope therefore, when I roll back the volume of our college history, and show you "the day of small things," you will not despise too much our petty number, our humble accommodations, our rude manners, our hard fare, our scanty rations and our limited curriculum of studies. Let not

Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile,

The short and simple annals of the poor.

When I first knew Chapel Hill in January, 1804, the infant university was but about six years old. Its only finished buildings were what are now called the East Wing and the Old Chapel. The former was then only two stories high, capable of accomodating one tutor and sixty students by crowding four into a room. The faculty consisted of three: President Caldwell, Prof. Bingham, and tutor Henderson. Their college

Page 581

titles were "Old Joe," "Old Slick" and "Little Dick." "Old Joe," however, was only thirty years of age and possessed (as you shall hear in the sequel) a formidable share of youthful activity. "Old Slick" derived his cognomen, not from age but from premature baldness, and the extreme glossiness of his naked scalp. And "Little Dick," a cousin of the late distinguished Judge Henderson, though he had a brave spirit, was not very well fitted by the size of his person, to overawe the three score rude chaps over whom he was placed as solitary sentinel. As a nursery of the college there was a preparatory school, taught by Matthew Troy and Chesley Daniel. All things were fashioned after the model of Princeton College, and that probably was fashioned after the model of the Scottish universities, by old Dr. Witherspoon. If this were the case, it would seem to account for the small quantum of instruction provided for us, if Dr. Johnson spoke the truth when he said of Scottish education, that "there every body got a mouthful, but nobody got a belly-full." Into this preparatory school, it was my fortune to be inducted, a trembling urchin of twelve years, in the winter of 1804. It was then a barbarous custom brought from the North, to rise at that severe season of the year before day-light and go to prayers by candle-light; and many a cold wintry morning do I recollect, trudging along in the dark at the heels of Mr., afterwards Dr. Caldwell, with whom I boarded, on our way to the tutor's room, to wait for the second bell. In that year I read Sallust's War of Jugurtha and Conspiracy of Cataline, under the tuition of Mr. Troy, of whom my recollections are affectionate, for he was partial to me, and taught me well for those times. But I can recollect some of my classmates, grown young men, upon whose backs he tried a blister-plaster, made of chinquepin bark, to quicken the torpor of the brain. Nor was he singular in his discipline. Whether boys were then duller or more idle than now, I know not, but at that time whipping was the order of the day. I had, before coming to Chapel Hill, served three years under it, at Hillbsoro', where Mr. Flinn wielded his terrible sceptre, and realized in our eye, the description of Goldsmith:

"A man severe he was and stern to view;

I knew him well, and every truant knew;

Well had the boding tremblers learned to trace

The day's disasters in his morning face."

This was literally verified with us, when Dr. Flinn came to school on Monday morning, with his head tied with a crimson bandana handkerchief. It was the bloody flag to us, and the very skin of our backs began to tremble.

After serving such an apprenticeship at Hillsboro', the exchange for Mr. Troy's administration was like exchanging the cowhide for the willow twig, for Mr Flinn's "little finger was thicker than Mr. Troy's loins." But

Page 582

now after drawing aside the pall of oblivion from these infirmities of the dead, I feel some twinges of remorse, as though I had rudely trodden on the ashes of my departed instructors; for, having been myself a teacher, all my life, I ought to know how to make allowance for the trials of teachers; and if any one of you, my hearers, is accustomed to rail at the tyranny of pedagogues, and to flatter yourself with the conceit, that if you were one, you would always be able to control your temper, I would only address you in the language which the advertisement uses respecting sovereign recipes: "Try it," and if in six months you don't go and hang yourself, you will, at least, have more charity for teachers, all the days of your life. I told you that I remembered Mr. Troy with gratitude; but I believe nothing he ever taught me, imprinted itself so deeply on my memory, as the burst of eloquence which the boys told me he had made, when he was a student, upon the charms of Miss Hay, afterwards the first Mrs. Gaston. Troy was given to the grandiloquent style, and on this occasion Miss Hay, who was the belle of the day, with a small party came to visit the Dialectic library. It was then kept in one of the common rooms inhabited by four students; and you may judge of the tumult that was excited by every such visitation, and how much sweeping and fixing up was required, and how many frightened boys ran to the neighboring rooms, and shut the doors, all but a small crack to peep through. On this memorable occasion, Troy had fixed himself in a corner of the room, whence he could contemplate the beautiful apparition in silent ecstacy. After she was gone, the librarian called him out of his trance, and said: "Well Troy, what do you think of her?" "Oh! sir, she's enough to melt the frigidity of a stoic, and excite rapture in the breast of a hermit;" to which he might have added:

"And like another Helen, has fired another Troy."

A man that could talk in that way, appeared to me, in those days, to have reached the top of Parnassus.

Having mentioned the library of one of the literary societies, I must carry you back, ye proud Dialectics and Philanthropies of the present age, to your humble birth, and reveal to you your inglorious antecedents. It may be good for you who now loll upon sofas and survey with triumph your thousands of volumes to look back fifty-five years, and glance your eye "into the hole of the pit whence ye were digged." The Dialectic library of this college, all of it, was then contained in one of the cupboards of one of the common rooms in the east building, and consisted of a few half-worn volumes, presented by compassionate individuals, and I think it was in the habit of migrating from room to room, as the librarian was changed, for you may be sure the responsibility of taking care of such a number of books could not be borne long by one pair of shoulders. And besides, there was some ambition

Page 583

to choose, as librarian, a man who could wait on the ladies with something of that courtly grace which distinguishes the marshals of this polished age. But the cavaliers of that early time, poor fellows! had to make their way to the ladies' hearts without any of the modern artillery of splendid sashes, moustaches and goatees. The naked face, with native flush or native pallor, was all their dependance. The cupboards were not only small but full of rat-holes, and a large rat might have taken his seat upon Rollins' History, the corner stone of the library, and exclaimed with Robinson Crusoe:

"I am monarch of all I survey,

My title there's none to dispute."

Such was the infancy of Dialectic knowledge; such the meagre fare provided for Dialectic literary appetite in those primeval days.

And what is told of one library may be told of the other, for they were as much alike as the teeth of the upper and the lower jaw, and as often came into collision. When one library got a book, the other must have the same book, only more handsomely bound, if possible. I am sorry to record that the contest between the two societies, at that time, was not confined to an honorable competition which should have the finest library, or the best scholars; but that it often amounted to personal rancor and sometimes seemed to threaten a general battle.

The societies then had no halls of their own, but held their sessions on different nights in the week in the old chapel, without any fire in the winter, and besides, with the northwind pouring in through many a broken pane. Think of this, ye pampered collegians, of this effeminate age, and bless your stars that your college times have come fifty years later. Before I come down to a somewhat later period, let me present you with a sketch of the scenes going on under these old oaks in the year 1804, fifty-five years ago, and let me draw from memory, if I can, a picture of the 4th of July of that year, for that was the commencement day--the great national festival being then the great college festival.

The waves of the revolutionary war seemed hardly to have subsided, and hence military feeling and military habits intruded upon academic shades and mixed themselves with the peaceful pursuits of literature. The great object of display on commencement day was not the graduates or their speeches, but a fourth of July oration, delivered by the General, who had been chosen by the vote of the whole body of students, preps and all, for free suffrage then prevailed, and a prep's vote was as good as any body's. The office of General and orator of the day was, of course, an object of great ambition; and while the election was pending, we preps felt our importance considerably augmented. Like the Nile, we always began to swell about the end of June; but our inundation was

Page 584

soon over, not lasting longer than the fourth of July. On these occasions the candidates would come down among us and take us in their arms and caress us most lovingly, and invite us to their rooms in college, and, I suppose, treat us there to gingercakes and cider, though as to that fact, I have no distinct recollection; but all of you who are versed in the ways of candidates, will admit it to be very probable that they did. As well as I recollect, there was elected, beside the General or orator, the General's aid. On this occasion Thomas Brown, son of the late Gen. Brown, of Bladen, and brother-in-law of the late Gov. Owen, was elected General, and Hyder Ally Davie, was second in command.

All things being duly arranged, the General, clad in full regimentals, with cocked hat and dancing red plume, placed himself at the head of his troops (for we were all turned into soldiers for the nonce) and marched up to the foot of the "Big Poplar," where was placed for him a rostrum, upon which he mounted, and, all the military disposing themselves before him, he gracefully took off his plumed helmet, and made profound obeisance to the army; and if a prep's bosom ever throbbed with proud emotions and ever thrilled with anticipations of the pleasure of being a great man, our hearts felt that throb and thrill on that day. I can tell you nothing of the graduating class, or their speeches. My childish fancy was taken up with the military display, though we had no music to march to but the drum and the fife. If we had had such a band as you have here to-day, it might have been too much for us--few perhaps would have survived it.

The ball at night was productive of an incident of some seriousness and importance. The old Steward's Hall, which some of you have reason still to recollect to your sorrow, was then the ball-room. The floor was covered with spectators, except the spots left vacant for the dancers. Of course the dancers had to pull their partners to their position through a dense thicket of gentlemen, five deep. This may well be called "threading one's way," I should think. In such circumstances dancing in the month of July, must have been delectable work, and must have always involved the risk of such unhappy rencounters as the one I am about to describe: Hyder Davie, aid-de-camp to Gen. Brown, in cutting the pigeon-wing before his partner, came down, rough-shod, upon the toes of Henry Chambers, of Salisbury. It was borne with, the first time, as an accident and overlooked; but upon coming round the second time, it was repeated, and consequently was obliged to be considered as an intended insult. The wounded toe, which is sometimes the seat of honor, called the offending heel out of doors, and demanded an explanation. It resulted in an engagement, in which Chambers gave a blow or two, for which he received a stab or two in the neck, from the pen-knife of Davie; for in

Page 585

those simple days bowie-knives were not invented, nor arms worn, except openly by soldiers. The next day a solemn trial of the case was held in the chapel, by the trustees, among whom were Gen. Davie, Col. Polk, (chairman,) Gov. Martin, Messrs. Cameron, Gaston, Nash and others, since the men of mark in our State. What decision the trustees came to, is not recollected, but I believe the combatants came off even. The ladies, the next day, were found to have taken sides, some for the heel and some for the toe, like the Little Endians and Big Endians, familiar to the readers of Gulliver.

I will detain you on this part of my subject only a moment, to call your attention to two things characteristic of the age. The first is, the spirit of the times indicated by the name Hyder Ally, given to his son, by Gen. Davie, and that of Tippoo Saib, given to his son by Maj. Pleasant Henderson. That two such men should have given their sons such outlandish names, in honor of two Hindoo despots and semi-barbarians, because they were at war with Great Britain, affords a lively idea of the old flame against the mother country, still burning in the breasts of the surviving officers of the revolution.

The second reflection suggested by the incident before us, is the diminutive size of the ladies of those days. How unambitious, how feeble minded they must have been to be contented with occupying no more space in the world, and in the eyes of men, to be pulled, that way, through a zig-zag maze of rough arms and shoulders, at the imminent risk of hanging by the hair or losing a comb or necklace in the transit. The ladies of the present day, have learned too well their just rights, to be satisfied with anything less than two thirds of this wide, wide world. There is no limit to their inventive genius when it is stimulated by an encroachment on their rightful domains. They have added to the dimensions of their fame, as well as of their persons, by giving birth to a new order of architecture. A modern fine lady is, herself, a novel and wondrous specimen of architecture. Look at those two delicate little ankles! From the time of the erection of the Parthenon--from the time of the erection of the domes of St. Peter's and St. Paul's, down to the erection of the domes at Washington or Raleigh, was it ever supposed--would it ever have been believed--did it ever enter into the heads of Phidias, Michael Angelo, or Sir Christopher Wren, that two such slender columns would have supported so stupendous a dome--especially columns constructed on the most unartistic of all principles, the inverted cone? It can be classed with no order of architecture now extant. We shall have to invent a new name for it, and I can think of none more appropriate than the Umbrella Order of Architecture. They who have dared to prop up such a magnificent fabric upon such a pedestal, have found out the pou sto of Archimedes, and can move the universe.

Page 586

It was at this commencement, (1804) I think that Greek was made a part of the college course. Gov. Martin, if I recollect, was the proposer of the measure. "You study logic," said he, "and you don't know the word from which the term is derived." No doubt the Governor gave some better arguments (if I had been old enough to cherish them) for substituting the classics of Greece for those of France, which last had then a factitious importance and popularity from the recent splendor of Voltaire, from our late obligations to the country of La Fayette, and from the overwhelming interest excited by the first French revolution. A little French had, before this time, been accepted in the place of Greek, and a Frenchman had been a necessary "part and parcel" of the faculty. Of course, to torment, him and amuse themselves with his transports of rage, and his broken English, was a regular part of the college fun. The trustees after some experience found that it was better to have French taught by a competent American, though with a little less of the Parisian accent, than to have to fight daily battles to redress the grievances of a persecuted monsieur. Greek after its introduction, became the bug-bear of college. Having been absent when my class began it, I heard, on my return, such a terrific account of it, that I no more durst encounter the Greeks than Xerxes when he fled in consternation across the Hellespont, after the battle of Salamis. Rather than lose my degree, however, after two years, I plucked up courage, and set doggedly and desperately to work, prepared hastily thirty Dialogues of Lucian, and on that stock of Greek was permitted to graduate. As for Chemistry and Differential and Integral Calculus and all that, we never heard of such hard things. They had not then crossed the Roanoke, nor did they appear among us, till they were brought in by the northern barbarians, about the year 1818. Yet notwithstanding the poor showing we could make as to faculty and course of study, the secretary of the board of that day, was very ambitious of opening a sisterly correspondence and communion with all the colleges of the United States. He sent for all their Latin Catalogues, and in order to be even with them, made up out of his own stock of Latin a Catalogue for us, and diffused it through the land, from Maine to Georgia. Now this was very unwise policy in that officer, for we were then in the very egg-shell of our existence, and ought to have concealed our nakedness from our mocking brethren of the North. This Latin pamphlet was in every respect a sorry looking affair. It was gotten up at Raleigh, on coarse paper, and it can be no offence now to say, that Raleigh was not at that era a fortunate place of issue for a Latin pamphlet. But what was worse, it was disfigured with several sad blunders in the Latin (for I don't know that Latin is any part of the qualifications of a secretary of the board) and exhibited to the admiring world the following imposing

Page 587

Senatus Academicus: PRESIDENT CALDWELL, who taught mathematics, natural and moral philosophy, and did all the preaching. YOUR HUMBLE SERVANT was professor of languages, in general, I suppose; all, ancient and modern; and WILLIAM D. MOSELEY (the future governor of Florida) was tutor. The professor of languages was of course responsible for this elegant and classical production, in which among other beauties, I recollect the treasurers of the board were called in conspicuous capitals TREASURARII! I writhed under the mortification a long time, and was always afraid of meeting a professor from the North, lest he should ask me what was the Latin for treasurer.

The South building, our neighbor over there, was then in an unfinished state, carried up a story and a half, and there left for many years to battle with the weather unsheltered; but still it was inhabited. "Inhabited!" you will say, "by what? By toads and snails and bats, I suppose." No sir, by students. Risum teneatis amici?

As the only dormitory that had a roof was too crowded for study, and as those who tried to study there spent half the evening in passing laws to regulate the other half, many students left their rooms as a place of study entirely, and built cabins in the corners of the unfinished brick walls, and quite comfortable cabins they were; but whence the plank came, out of which those cabins were built, your deponent saith not. Suffice it to hint that in such matters college boys are apt to adopt the code of Lycurgus: that there is no harm in privately transfering property, provided you are not caught at it. In such a cabin your speaker and dozens like him hibernated and burned their midnight oil. As soon as spring brought back the swallows and the leaves, we emerged from our dens and chose some shady retirement where we made a path and a promenade, and in that embowered promenade all diligent students of those days had to follow the steps of science, to wrestle with its difficulties, and to treasure up their best acquirements: Ye remnants of the Peripatetic school!

"Ah! ye can tell how hard it is to climb

The steep where fame's proud temple shines afar!"

They lived sub dio, like the birds that caroled over their heads. "But how," you will say, "did they manage in rainy weather?" Aye, that's the rub. Well, nothing was more common than, on a rainy day, to send in a petition to be excused from recitation, which petition ran in this stereotype phrase: "The inclemency of the weather rendering it impossible to prepare the recitation, the Sophomore class respectfully request Mr. Rhea to excuse them from recitation this afternoon." To deliver this mission to the Professor I was appointed envoy ordinary (not extraordinary) and plenipotentiary, being a little fellow hardly fifteen, and

Page 588

perhaps somewhat of a pet with the teacher. The Professor, a good-natured, indolent man, after affecting some vexation, (though he was secretly glad to get off himself), and pushing the end of his long nose this way and and that way some half dozen times with his knuckles, concluded in a gruff voice with: "Well get as much more for to-morrow." The shout of applause with which I was greeted upon reporting the success of my embassy resembled, (if we may compare small things with great,) the acclamations with which Mr. Webster was hailed by the nation upon happily concluding the Ashburton treaty in 1842, by which war with Great Britain was prevented. Mr. Webster may have been greater, but he was not prouder than I was at the successful issue of my negotiations. Who knows but I might have been a first rate diplomate, if I had followed up these auspicious beginnings! And what do you think was the lesson from which a deliverance for one day was the occasion of such tumultuous joy? Why it was Morse's geography, which was then the main Sophomore study, contained in two massy octavos, and to recite off which, like a speech, page by page, was the test and the glory of the first scholar of the class.

Dr Morse was, with us, the great man of the age, and stood as high as does now his son, the inventor of the telegraph; and that notwithstanding he had stigmatised our State by mentioning under the head of "manners and customs of North Carolina," that a fashionable amusement of our people in their personal rencounters was, for the combatant who got his antagonist down to insert his thumb into the corner of his eye and twist out the ball; which elegant operation they called gouging. This slur upon national character would, now-a-days, have banished his book from our State. It excited so much the wrath of one of our representatives in Congress, Wm. Barry Grove, of Fayetteville, that he declared if he ever met with Dr. Morse he would gouge him. He did meet with the Doctor, who had heard of the threat, but instead of executing his purpose they had a hearty laugh over the story, Dr. Morse alleging that he had derived the account from Williamson.

Our geographical recitations were enlivened by some rare scenes, one or two of which I will venture to relate, though they are almost too farcical for this dignified assembly, and yet they are among the things, "as my Lord Verulam remarks, which men do not willingly let die." The class was reciting on Greenland. The youth under examination was -- --, I do not feel safe to mention his name, for he may be here among us for aught I know, (the speaker looking anxiously over the crowd,) but if he is, he will be easily known by the length of his ears, and there are no animals on earth that bite and kick harder than the long-eared tribe. We will, therefore, indicate him by the name Sawney.

Page 589

Mr. Sawney, says the Professor, can you tell me anything about the animals of Greenland? "Yes, sir, there's one called the seal." What kind of a animal is it? "I dont remember exactly, sir, but I believe he says it is a very amphib--a very amphibiobus kind of animal sir." The boys plagued him about this new kind of animal until he became as irritable as a nest of wasps by the way-side. Another student, whom we will disguise under the name of Riggie, used to amuse various companies by telling the story upon Sawney. Now Riggie was the last man that ought to have made people merry over the blunders of others, for he had got his own nickname by his ludicrious pronunciation of Riga, a Russian town on the Baltic. He was asked what were the chief towns in Russia? He mentioned several, and among them Riggie on the Baltic, pronouncing the first syllable of the last word as it is heard in balance. The name Riggie stuck to him forever afterwards. But it often happens that he who smarts most under a joke is most ready to avert pursuit by throwing ridicule upon others--as in the street, the thief, hearing the hue and cry after him, escapes by echoing the cry "stop thief!" and joining in the chase. Sawney, goaded by Riggie's persecution, determined to avenge himself; so he laid a trap for him. He got a friend to invite a company including Riggie into his room, and to call for the story, while in the meantime, Sawney concealed himself under the bed. Riggie, alas! unconscious of the Trojan horse within the walls, was going on with his story, full sail, the audience convulsed with the enjoyment of the present and the anticipation of the paulo-post-future; when in the very fifth act of the drama, out popped Sawney from his ambush, and pitched into the dismayed comedian. I shall not attempt to describe the battle; but it may well be supposed that Sawney, stung with wounded pride and bursting with long imprisoned rage, fought with more desperation, and that his adversary, startled by a foe emerging suddenly from ambush, must have fought to a disadvantage. That was the last time I imagine that Riggie, or any body else, told the story of amphibiobus, nor would it have been revived to-day had I not trusted that a lapse of more than fifty years had either removed our hero from the reach of all earthly ridicule, or mollified his resentment into merriment; or at least, that being unnamed in my annals, he would take care not to write his name under the picture by attacking me. But if he or any other witness of the facts were here to challenge my truth and to show what a good story I had made out of nothing, I suppose you all would thank him about as much as you would thank a man, who, after you had dined pleasantly, as you supposed, upon a good fat hare, should come forward, show you the paws and convince you that what you had enjoyed so sweetly, was nothing but a cat.

Page 590

Such adventures as the foregoing were more apt to happen with sophmores than with other classes. To save them from the clutches of Dr. Morse, on a rainy day, was one of the chief honors of my sophomore year. Sophomores have always been hard fellows to deal with. This results from their amphibious nature, and colleges have given them a name (sophos moros) expressive of their compound character, partly wise and partly foolish. They are in a transition state, half-man and half-boy; their voice alternating in a most ludicrous manner between the alto and the bass, so that, in the dark you would suppose it was two persons talking. Their compositions too have the same mixed character; like comets they have a small nucleus with a prodigious expanse of tail.* Let not my young friends present, who happen to be sophomores, take umbrage at these pleasantries. I am not describing the sophomores of the present day, nor any specific sophomores. I am describing sophomores in the abstract, not in the concrete, and of course, no individual has a right to appropriate the description to himself, since the sophomore concrete has always specific peculiarities which shield him from being identified with the sophomore abstract. Besides the glory of a sophomore is not in what he is, but in what he is to be. He is an eaglet. Now an eaglet, just begining to be fledged, may not be a very comely bird, and its attempts to fly may be rather awkward; but then in a month or two, he is to be the bird of Jove, soaring into the eye of the sun, and bearer of the thunderbolt.

* In Webster's Dictionary, Mr. Calhoun's authority is given for the word sophomorical in this sense.

JUNIOR LIFE.--Let me now give a sketch of junior life,some fifty years ago in these precincts. There being but three teachers in college, (president, professor of languages and tutor,) the seniors and juniors had but one recitation per day. The juniors had their first taste of geometry, in a little elementary treatise, drawn up by Dr. Caldwell, in manuscript, and not then printed. Copies were to be had only by transcribing, and in process of time, they, of course, were swarming with errors. But this was a decided advantage to the junior, who stuck to his text, without minding his diagram. For, if he happened to say the angle of A was equal to the angle of B, when in fact the diagram showed no angle at B at all, but one at C, if Dr. Caldwell corrected him, he had it always in his power to say: "Well, that was what I thought myself, but it ain't so in the book, and I thought you knew better than I." We may well suppose that the Doctor was completely silenced by this unexpected application of the argumentum ad hominem. You see how good a training our youthful junior was under, by a faithful adherence to his text, to become a "strict constructionist" of the constitution, when he should ripen into a politician.

Page 591

The junior having safely got through with his mathematical recitation at 11 o'clock, was free till the next day at the same hour. And the first thing he had to determine was, what would be the most agreeable method of spending the rest of the day. Shall he ramble into the country after fruit, or shall he go a fishing, or shall he make up a party and engage a supper in the suburbs, at "Fur Craigs?" The last measure was often adopted, because of our hard fare at Commons. Accordingly a party of of some half dozen would go out and engage a supper of fried chicken, or chicken pie, biscuit and coffee. It was waited for with extreme impatience, and many yawnings and other symtoms of an aching void. At length it came upon the table, like the classical coena of the Romans, about three or four, P. M. The guests sat down, at twenty-five cents per head; and if you consider the leanness of our dinners at the Steward's Hall, you will be apt to suspect that the entertainer did not make much by that bargain. I'll tell you what, gentlemen, it will do well enough for you, who live in these palmy times, and fare sumptuously every day, to call the University your alma mater, your benigna parens, and all that, now that she is grown to be a fat, buxom lady, with a snug clear income of fifteen thousand a year. But when I first knew her, she was a very poor woman, and her children of those days would have more appropriately called her "pauperima mama!" for she dealt out very scanty allowance to her family either for body or mind, and treated her sons as movers to our new States treat their horses; she turned them out at night to pick up what they could. The truth is, her mother the State, acted a very unnatural part towards her, and, soon after she was born, seemed to take a dislike to her own offspring, and to try to starve it. Do you wish to know the ordinary bill of fare at the Steward's Hall, fifty years ago? As well as I recollect board per annum was thirty-five dollars! This, as you may suppose, would not support a very luxurious table, but the first body of trustees were men who had seen the revolution, and they thought that sum would furnish as good rations as those lived on who won our liberties. Coarse corn bread was the staple food. At dinner the only meat was a fat middling of bacon, surmounting a pile of coleworts; and the first thing after grace was said (and sometimes before) was for one man, by a single horizontal sweep of his knife, to separate the ribs and lean from the fat, monopolize all the first to himself, and leave the remainder for his fellows. At breakfast we had wheat bread and butter and coffee. Our supper was coffee and the corn bread left at dinner, without butter. I remember the shouts of rejoicing when we had assembled at the door, and some one jumping up and looking in at the window, made proclamation: "Wheat bread for supper boys!" And that wheat bread, over which such rejoicings were raised, believe me

Page 592

gentlemen and ladies, was manufactured out of wheat we call seconds, or, as some term it, grudgeons. You will not wonder, if, after such a supper, most of the students welcomed the approach of night, as beasts of prey, that they might go a prowling, and seize upon everything eatable within the compass of one or two miles; for, as I told you, our boys were followers of the laws of Lycurgus. Nothing was secure from the devouring torrent. Beehives, though guarded by a thousand stings--all feathered tenants of the roost--watermelon and potato patches, roasting ears, &c., in fine everything that could appease hunger, was found missing in the morning. These marauding parties at night were often wound up with setting the village to rights. I will relate one of these nocturnal adventures, and it was only "unum e pluribus." I must premise that Dr Caldwell seems to have made it a part of his fixed policy, that no evildoer should hope to escape by the swiftness of heels, and that whoever was surprised at night in any act of mischief, should be run down, caught and brought to justice. Whether the Doctor brought that feature of his policy from Princeton, where he was educated, or whether, being conscious that nature had gifted him with great nimbleness of foot, he was a little ambitious of victory in that line, I will not determine; but certain it is, that he was in the habit of rambling about, at night, in search of adventures, and whenever he came across an unlucky wight engaged in taking off a gate, building a fence across the street, driving a brother calf or goat into the chapel, or any similar exploit of genius, he no sooner hove in sight than he gave chase; nor did the youthful malefactor spare his sinews that night; for be knew that if he ever ran for life or glory, now was the time. Homer makes his hero Achilles, the swiftest as well as the bravest on the plains of Troy. No foe could match him in battle or escape him by flight. Dr. Caldwell was the podas okus Achilles of Chapel Hill, and he had more occasion for powers of pursuit than of contest, for his antagonists uniformly took to flight. You call this a "fast age," gentlemen, and so it is, but I don't know a man of this generation who is faster than was Dr. Caldwell. He liked to go fast in everything, and therefore he was not satisfied to take two days in getting to Raleigh. He and I have set out for the metropolis in the morning, and stopt the first night at Pride's, ten miles this side, such was the state of the roads. Who knows but such snail-like progress as this suggested to him the first idea of the present railroad from Beaufort to the mountains, the honor of which, I believe, is now conceded to him? Now, O! muse, that didst inspire Homer to describe Achilles' pursuit of Hector, three times round the walls of Troy; or thou gentle muse, who didst breathe thy soft afflatus upon Ovid when he described the race between Apollo and fair Daphne; or thou Caledonian muse, who didst

Page 593

preside over Walter Scott, when he sung the race of Fitz James after Murdock of Alpine, or over Robert Burns, when he made immortal the flight of Tam o' Shanter from the witches,--either of you or all of the nine at once, assist me to describe the race between President Caldwell and Sophomore Faulkner, on the night of the --day of --, 18--. The President lived at that time where his successor now lives, and was returning about bed time "from walking up and down upon the earth,"* to see if any of the students were--where they ought not to be. As he was mounting the stile which stood where Dr. Wheat's south-east corner now stands, he spied two young men, busily engaged in building a fence from that corner across the street to the opposite corner. This, by the way, was always the difficulty in carrying out the manual labor system in our schools, and constituted the grand distinction between negro-labor and student-labor: that the negro fenced in the field and hoed up the weeds; the student hoed up the cotton and fenced in the street. The lads had just before his appearance heard that portentous snapping of the ankles, which was a remarkable peculiarity of Dr. Caldwell's locomotives and was very useful to the evil-doers in enabling them to get several yards the start in the race. As soon as they heard this premonitory crepitation (which, I suppose, they were wont to consider as a providential forewarning of danger, like the rattle of the rattle-snake) one of the fencemakers, whose nom de guerre was Dog, skulked into a corner and was passed by. Faulkner sprang forward. But I forgot that Homer always spends a line or two in describing his heroes, before he brings them into action. So I must suspend the race, till I have given my audience some idea of Faulkner's person and character. He was a tall, bony, gaunt and grim looking fellow, with shaggy threatening eyebrow--had been at Norfolk during the war of 1813-'14, as a soldier or officer, and had contracted a soldier's love of adventure and frolic, and like Macbeth, would have run from nothing born of mortal, if he had been engaged in a good cause. But building a fence across the street at night, his conscience set down as a deed of darkness, and therefore proved like the conscience of one of the murderers of the Duke of Clarence in Shakspeare's Richard III. "This thing conscience," says he, "is a blushing, shame-faced spirit, that mutinies in a man's bosom; it fills one full of obstacles. A man cannot steal but it accuseth him; a man cannot swear but it checks him. It made me once restore a purse of gold that

* Should any of my more serious readers complain of an impropriety in this quotation from Job 1: vii; they will perhaps find an apology for the allusion in the fact, well known to all alumni of that period, that Diabolus shortened into Bolus, was the common nickname of the President, and that while engaged in their deeds of darkness, they would just as willingly have seen the one as the other.

Page 594

by chance I found. It beggars any man that keeps it. I'll not meddle with it. It is a dangerous thing. It makes a man a coward." So it proved with the soldier of Norfolk on that memorable night. His conscience made him a coward, but perhaps it enabled him to run the faster on that occasion, and he might have escaped had any but "the swift-footed Achilles" given chase. But fate had doomed him to lose this race:

Forth at full speed the fence-man flew--

Faulkner of Norfolk prove thy speed,

For ne'er had sophomore such need;

With heart of fire, and foot of wind,

The fierce avenger is behind;

Fate judges of the rapid strife,

The forfeit death, the prize is life.

He leaves the gates, he leaves the walls behind

Achilles follows like the winged wind;

Thus at the panting dove a falcon flies,

(The swiftest racer of the liquid skies;)

Just when he holds or thinks he holds his prey,

Obliquely wheeling through the ærial way,

With open beak and shrilling cries he springs,

And aims his claws and shoots upon his wings,

Just so around and round the chase they held

One urged by fury, one by fear impelled;

Thus step by step where'er the Trojan wheeled

There swift Achilles compassed round the field;

So on the laboring heroes pant and strain,

While that but flees and this pursues in vain;

Thus three times round the Trojan walls they fly,

The gazing gods lean forward from the sky,

Jove lifts the golden balances that show,

The fates of mortal man and things below;

Here each contending hero's lot he tries

And weighs with equal hand their destinies.

Low sinks the scale surcharged with Faulkner's fate--

Thus heaven's high powers the strife did arbitrate:

Just then the Faulkner tripped, and prostrate fell,

And on the sprawling body pitched--Caldwell!

Having thus disposed of one of the fence-makers, the victorious President went back in quest of the other, who instead of coming to the assistance of his friend, had lost no time in leaving the field of action. The President after beating the bush awhile, returned to the college, where in the mean time, Faulkner, with clipped wings and fallen crest, had gathered a party in one of the rooms, and was telling the fortunes of the night. Little did he dream that his exulting conqueror was standing close by, in the dark, listening to every word. "And what became of Dog?" inquired one of the party. "Oh! Dog, he took to the woods and I dare say he is running yet." When the court met, the next day, to try the delinquents, it appeared in evidence from the tutor, that Dog was the sobriquet of Junius Moore. He was accordingly startled by a summons served upon him by old Daniel Bradley, the college constable, to appear

Page 595

before the faculty as particeps criminis with Faulkner. They were both charged with what the lawyers might call tortuously doing a tortuous act. In plainer language with feloniously, wickedly, and with malice afore-thought, then and there, laying down, making, building and constructing a Virginia fence across the street, against the peace and dignity of the State. Gentlemen, you who have read Cicero's graphic description of the confusion of face and dumbfoundedness of Cataline's accomplices when the consul confronted them with all the damning evidences of their guilt, you can conceive and none but you, the looks and behavior of the two fencemakers, when Dog was thus unexpectedly arraigned at the bar. "They were so amazed and stupefied," says Cicero, "they so looked upon the ground, they so cast furtive glances at each other, that now they seemed to be no longer informed on by others, but to inform on themselves." What the faculty did with the offenders I do not recollect, but remember, young gentlemen, it is all upon the faculty-book, and I hope none of you are ambitious of a place in that chapter of the history of the University or to be enrolled in the Newgate calendar.

As for Dog, he deserved a better name, for he was a native born poet, and he and Philip Alston (a graduate of 1829,) are among the few of our alumni on whose birth Melpomene did smile. Had Moore lived he might have written something to justify these praises. Alston lived long enough to leave some memorials of his genius, but, alas! not long enough for our fame or for his own.

"For Lycidas is dead, dead ere his prime--

Young Lycidas--and hath not left his peer!"

That night was one of the Noctes Atticæ or Ambrosianæ, if you choose so to name them, which signalized the early history of this college. Dr. Caldwell was a good man and a wise man; but I wonder he did not see, that the olympic games of Greece had not a greater attraction for that sprightly people, than such night adventures have for some freshmen--sophomores--juniors--shall I go on? and that for the chance of such a race as this, many a wild collegian would run all the risk of suspension, three nights of every week.

And here, perhaps, it will not be offensive to introduce, among my reminiscences, the shadow of a reminiscence, which rests like a penumbra among the more distinct impressions on the tablet of my memory. It relates to a man who has long borne a conspicuous and honorable part among the editors of our country--one of the surviving Titans, who has planted his battery not five miles from the throne of Jove, and hurled many a thirty-two pounder at the whitehouse and at the capitol. Should this page chance to meet his eye, and should he recognize in it a faint nucleus of fact, he will laugh at a college legend which always hands down

Page 596

a much better story than it received. President Caldwell once caught some boys in mischief; among the rest he descried one on the top of the college, fastening a goose to the very ridge of the roof. "Ah! Joseph, Joseph," said he "I suppose thou art fixing up that poor bird there, as an emblem of thyself." Perhaps that severe cut from his teacher may have goaded the youthful truant to throw away the goose forever afterwards, reserving only a quill wherewith to write himself into renown. I hope he will forgive me for thus heralding his exploits upon the house-tops.

The bell, too, that everlasting mischief-maker, could never be confined to its legitimate utterances, as long as its notes, at dead of night, set all the faculty on the "qui vive," and when a string, passing from it to some upper window, enabled a freshman, to whom it was a novelty, to create mysterious music, as if gotten up by the spirits of the air. But since the faculty have put it upon the ground that sometimes little boys come here just after their mothers have taken the rattles from about their necks and that they must be amused a while with some noise as a substitute, the officers indulge such in bell-ringing until they have got their fill, and then the nuisance is abated.

As for myself, being brought up in the Caldwellian school, I once did try my hand at a night adventure, and sallied forth to catch a party of revellers in the woods. I came upon them by surprise and captured several, but in pursuing one, I got hung in a grape vine, which cured me of pursuing students at night.

There was one other adventure, however, in which pars magni fui. As it is characteristic of the times, I will beg pardon for relating it. The two societies, as I have already intimated, were then often at dagger's points with each other, and were sometimes in danger of a general engagement. Like all young things, they easily got angry, and had no objections to a fight, while older animals grow wiser, and find peace much more comfortable and much more dignified than war. (I beg pardon of the august crowned heads that are now butting each other on the plains of Italy*.) On one occasion the champions of the respective bodies came into collision and had a desperate fight, in which one of them, much more of a bully than the other, got his antagonist down and beat him most dreadfully, though I never heard that he gouged him. It was a kind of melee, several being engaged on both sides. Dr Caldwell thought it absolutely necessary to adopt vigorous measures to put a stop to such outrages. It appeared that the bully had provoked the fight, and was most to blame. So a writ

* That old commentator on the Bible, Matthew Henry, as full of wit as of wisdom, remarks that the prophets very fitly represent the great conquerors of the earth, under the emblems of lions, leopards, bears, rams, he-goats, &c. If so, our allusion in the text is not inapposite, and the world need not care much which has the hardest head, the ram or the he-goat.

Page 597

was taken out to arrest him and carry him to Hillsboro', where the superior court was then sitting. The President's posse comitatis was summoned to take him. The house where he secreted himself was surrounded the besieged leaped out upon the shed, and attempted to jump down; but being headed on all sides, he surrendered at discretion. I was one of the guard to Hillsboro.' It was a rainy night, the prisoner purposely kept his horse in a walk, that we might not bring him into town at night as a guarded criminal. So we rode up at breakfast time, like a party of travelers, to the hotel, where the judge and prosecuting officer, and a crowd of people were standing. Our mittimus was examined, when lo and behold! the justice of the peace who issued it, had, either accidentally or on purpose, left out of the writ the initials of his office "J. P.," and without those magic letters, it was as harmless as a lion with his head cut off. So the whole proceeding was quashed, the prisoner discharged, the expedition covered with ridicule, and the escort went home pretty well sick of sheriff's business. I beg you, gentlemen in authority here, if you ever have a like occasion, remember the letters J. P.

While we are passing over certain early incidents of Dr. Caldwell's administration, before I leave the subject, the audience will no doubt indulge me in here introducing a brief notice of one of his most valued colleagues and coadjutors, the late lamented Dr. Mitchell. Here let us pause to drop a tear to the memory of this martyr of science. He fell a victim to too great self-reliance. This trait in his character, owing no doubt, in a considerable degree to constitutional temperament, was stimulated and confirmed by a New England education, in which youth are seldom indulged in that life of ease and indolence so common and so pernicious among ourselves; but are early thrown upon their own enterprise, and invention, and industry, for providing their future livelihood. This characteristic of that part of our country, is remarkably calculated to develop all the latent energies within a youth, whether for good or for evil--a stern necessity "to do or die"--to swim or sink, which may produce a a Franklin and a Webster, or peradventure a Benedict Arnold--like the fierce sun of the tropics, which concocts at once the aromatic gums and the deadly poisons.

This self-reliance of our regretted friend, was conspicuous from his first appearance among us. It carried him as a botanist, over almost every hill and meadow, and into every nook and corner of our extensive State, alone and through all weathers; and led him, as a geologist, to scale every mountain and penetrate every cavern, where nature might promise spoils to philosophic curiosity. While youth remained, he escaped unharmed from the perils into which his adventurous spirit pushed him; but, like Milo, the famous athlete of Crotono, he forgot that he was

Page 598

growing old, and was lured to his death by too great confidence in that strength and activity on which he had so often relied with safety. At his age and with his high position as a savant, he was entitled to an escort. He ought not to have been seen venturing alone and unassisted among precipitous cliffs, to make good North-Carolina's claim to the Chimborazo of the Alleganies. He ought to have had a retinue of enthusiastic pupils at his heels, (magna comitante caterva,) carrying his chain and his compass, and his barometer, and his tent and traveling chest. And I have no doubt he might have enlisted such a corps of his pupils had he desired and requested it. But his self-reliance seemed to scorn all help, as a confession of incapacity and dependance. A bivouac in a mountain gorge, alone and far from the haunts of men, had something in it inviting to his bold and inquisitive genius. I think I have heard him say, that in one of his visits to the same mountainous region, he had been drenched to the skin by a thunder-storm, and had laid down and slept in his wet clothes, till the morning. That such a man would fall prematurely by his excessive spirit of adventure, was naturally to have been apprehended, and we might have justly cautioned him, in the language of Andromache:

"Too daring man, ah! whither wouldst thou run,

Ah! too forgetful of thy wife and son;

For sure such courage length of life denies,

And thou must fall, thy virtue's sacrifice!"

I have such an opinion of my late friend's undaunted spirit of adventure, that I believe, if he had been one of the scientific corps who accompanied Napoleon in his expedition to Egypt, and if that general had summoned them all before him and said: "I want a man who will go to the biggest of the pyramids, find its secret entrance, explore, lamp in hand, its dark winding galleries, search its inmost penetralia and bring out, if to be found, the sarcophagus of Chcops himself"--I believe that Elisha Mitchell would have stept forth and said: "I'll try it." He would have been the very man to have joined Dr. Kane in his Arctic expedition. That daring navigator pushed his investigations to latitude 82° 30', the farthest hyperborian point ever reached by the foot of science, and laid down the coast to within less than 8° of the pole. But if Mitchell had been along with him and Dr. Kane had detached him on an exploring trip, I should not have wondered if the pole itself had been discovered, and Mitchell had tied his boat to the axis of the earth! Shade of my departed companion! forgive this sportive ebullition to which I have been tempted by the recollection of thine own jocose temper and playful spirit. How often, when I have gone to thee, gloomy and fretted by some transient irritation, has thy contagious hilarity and sunshiny face dispelled the cloud from my brow and the spleen from my

Page 599

temper, and I felt the truth of that inspired sentiment: "As iron sharpeneth iron, so does a man sharpen the countenance of his friend." Of such a man might be said, in the beautiful language of Dr. Johnson, that "his death has eclipsed the gaiety of his country and impoverished the general stock of harmless pleasure," as well as of valuable science.

But, brothers of the alumni, I could not excuse myself, and I should but ill perform the duty committed to me this day, if I devoted the whole of this address to amusing or mournful reminiscences of the past. I wish to say something before I sit down, which will be profitable for the future. It may be allowable, on a joyous anniversary like the present, to entertain ourselves and our audience, with some pictures of college life, half a century ago. But it becomes us as educated men, who have gone through the perils and who have reaped the fruits of a collegiate career, to direct our thoughts to the great question how these perils may be encountered and these advantages secured with the least admixture of evil. As lovers of our common country--as North-Carolinians, ambitious of the honor of our State--as men bound to feel for those many parents who trust to these walls their dearest treasure--their sons, that are to bless or to blast their homesteads--we ought to make it a subject of anxious thought, how to prevent a great college from being a great calamity. As men of reflection and humanity, we must have been often saddened by observing the vast amount of waste in human life, human talent and human happiness, which the spectacle of our colleges presents. That there is a strong tendency, when large numbers of young men are congregated together, and live to themselves, with very little intermixture with general society, to become dissipated, riotous and lawless, the history of all colleges proves, both in this country and in Europe. The two universities of England have been long famous as the abodes of licentiousness of all kinds. Mr. Griscom, one of the most respectable and intelligent citizens of New York, visited Oxford about forty years ago, and after witnessing a disgraceful scene enacted by a party of students at the hotel* makes the following reflections: "Alas!

* "Of the morality of some of the collegians, I had a most unfavorable specimen. Four or five of them came in the evening, to the inn where I had taken up my quarters, in the principle street in the town. They entered the coffee room, where two or three travellers and myself were sitting engaged in conversation. And after surveying us and the room for some time, they went out but shortly after returned, seated themselves in one of the recesses into which the room was divided, and ordered supper and drink. Their conversation soon assumed a very free cast, and eventually took such a latitude as, I should suppose, would set all Billingsgate at defiance. They abused the waiter, broke a number of things, tore the curtains that enclosed the recesses--staid till near twelve o'clock, and then went off, thoroughly soaked with wine, brandy and hot toddy. I was told the next morning, that two of them were noblemen." (A very different thing from NOBLE MEN.)--Griscom's Year in Europe, vol. 1. pp. 60, 61.

Page 600

for such an education as this. What can Latin and Greek and all the store of learning and science have to make amends in an hour of retribution, for a depraved heart and an understanding debased by such vicious indulgence. I cannot but cherish the hope that this incident does not furnish a fair specimen of the morals of the students. It will doubtless happen, that in so large a number as that here collected, in the various colleges, many will bring with them habits extremely unfavorable to morality and subordination. But from the information derived from my guide, who was a moderate man, and certainly well informed with respect to the habits of the place, and from the observations which forced themselves upon me in my walks through the streets and gardens, this evening, I am obliged to deduce the lamentable conclusion that the morals of the nation are not much benefitted by the direct influence of this splendid seat of learning." And although he inclines to the opinion, that the state of morals is not quite so bad at Cambridge, yet he admits it to be a doubtful question, and that this is only a surmise of his own, and says: "It would be a curious and interesting subject of inquiry to ascertain, with as much accuracy as possible, the comparative morality of Oxford and Cambridge, as it is admitted that in Oxford the collegiate studies are directed with paramount assiduity to moral philosophy and the higher range of classical learning, while in Cambridge, mathematics and natural philosophy have a transcendent influence."*

* There is one feature which Mr. Griscom observed at his visit to Cambridge which is certainly significant, and ominous of a low state of morals. "Since the late peace," says he, [this was written in 1819, soon after the anti-Napolean armies had been disbanded,] "a great number of persons, from the army and navy, have entered as students of divinity, relying on family influence for promotion, and in consequence of such influence, no inconsiderable number have been promoted, and over the heads, too, of others, who have devoted many years to the duties of the university. Surely no wound can be inflicted on religion more deep and deadly than to place a man by the mere dictum of hierarchical authority, in the station of a Christian minister, who is just reeking from the camp, and who has no qualifications either of head or heart for the solemn office, and probably no taste for any of its accompaniments except for the loaves and fishes."--Vol. 2: p. 210.

What license, what scorn, what blasphemy, what atheism, must the rowdies of Cambridge feel at liberty to indulge in, when they see the disbanded debauchees of the camp suddenly turned into pastors, having the care of souls!

This testimony relates to the state of things at those celebrated universities forty years ago. Have things inproved there since that date? Let us hear the testimony of Sydney Smith, one of the most distinguished literati of the present century, whom none will suspect of too austere and puritanical a view of the subject. In a letter written but a few years ago, to one of his female correspondents, he says: "I feel for Mrs.----

Page 601

about her son at Oxford, knowing as I do, that the only consequences of a university education are the growth of vice and the waste of money."*

* Life, vol. 2: p. 402.

In the German universities so far as reports have been published among us, the state of morals is even worse, the frequent practice of duelling being added to the usual vices of college life.

To come nearer home, what has been the experience of our neighboring sister South Carolina? In the beginning of this century, she began to awaken to the duty and the policy of providing means for the home education of her sons, who had hitherto been educated In the Northern States or in Europe. Somewhat later than we, she created a State college, and endowed it with that enlightened liberality worthy of the intelligence and opulence of her leading men. But, alas! the history of that college proves how useless it is to make all these magnificent preparations of faculty, of library, of apparatus and of buildings, if there are not materials enough of the right kind out of which to make students--if the young men of the country are reared up ease, idleness and luxury, and know that they are rich enough to do without an education. What is the usual course with such young men? They go to college; they there find numbers of idlers like themselves, they find study irksome and disgusting, pleasure spreads out her seductions before them, they are indulged with plenty of money, and habits of ruinous dissipation follow as the necessary results. If they are sent home, what penalty there awaits them? A horse a gun, a dog, fine clothes, and the ladies! Who would immure himself in a college cell with such companions as Thucydides and his crabbed Greek, or Loomis's Differential and Integral Calculus, when by going down street and "getting up a row," he can be sent home to so much pleasanter employment and company? The result of South Carolina's experiment upon a college, we have from authority the most unsuspicious and authentic. One of the most respectable alumni, one of the oldest judges on the bench of that State has given his testimony, which has been copied into most of the newspapers of the land. "I have known that institution," says Judge O'Neall, "intimately since 1811, when I first entered its walls, and I have no hésitation in saying that one fourth of its students have been affected injuriously or destroyed by intoxicating drinks. Indeed I fully believe that one fourth of its graduates sleep in drunkards' graves." He goes on to say, however, that "notwithstanding this dread scourge, South Carolina college has accomplished an immense amount of good," &c. A valuable lesson was learned from the results of the Cooper administration of that institution. Dr. Thomas Cooper was called to the presidency from his high reputation as a man of science and general learning, and perhaps with some reference to his orthodoxy

Page 602

on political questions, then deeply agitating that State. It would have been hard to find a man of more multifarious learning. He was a lawyer, a statesman, a physician, a philosopher, natural and moral, and somewhat even of a theologian; but withal he was an infidel, an atheist. And the college soon took the type of its head. Infidelity and irreligion took possession of the seat and centre of knowledge, and therefore soon became rife through the State. A State college is the eye of the body politic, and "if the eye be evil the whole body shall be full of darkness." The college was broken down by dissipation and disorder; parents lost all confidence, and durst not expose their sons to the double danger of infidel principles and profligate example. At length Gov. McDuffie in his message to the legislature, was obliged to report the State college as a failure; and though an infidel himself, he candidly admitted that the prevalence of infidel sentiments had destroyed the public confidence and reduced the college to its present low condition, and he therefore advised a reorganization of the faculty and a new trial for success under different auspices. Accordingly three of the foremost men in the State for talents and religious character, were installed as president and professors, and a special professorship was created of Christian Evidences. Very soon the colloge regained its former patronage, religion was respected, the gospel powerfully preached twice every Sunday in the college chapel and infidelity, formerly triumphant and open-mouthed, was now silent and humbled, if not extinct. Here was an experiment whose fruits I trust will be permanently and extensively useful, namely: that a literary institution, without the religious element to leaven the mass, will not be supported by the people of this country.

The University of Virginia had to go through the same experience. It was the child of Mr. Jefferson, whose infidelity was well known and had a contagious influence on the leading public men of the State. No provision was made for any religious worship or religious instruction in the university. The institution for several of the first years of its existence had a bad name for vice and irreligion--the religious public mourned and complained that the State university founded and supported by the votes and the treasure of the commonwealth, for the education of the sons of the commonwealth, should ignore christianity, and be given up to anti-christian influences. This was the apparent design, by leaving out religion entirely in the course of instruction and in the appointment of officers. To do Mr. Jefferson justice, this seems not to have been in his contemplation. Unbeliever as he was, himself, he was too shrewd a politician and too well acquainted with the people of this country, to attempt a literary establishment among us, having none of the moral and popular influences of christianity. His idea was this, as I learned from his own lips, when

Page 603