Sergeant Hallyburton, the first American Soldier Captured in the World War:

Electronic Edition.

Hyams, Charles W.

Funding from the State Library of North Carolina

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Leslie Sult

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Leslie Sult, and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2002

ca. 100K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2002.

Source Description:

(title page) Sergeant Hallyburton, the first American Soldier Captured in the World War

Charles W. Hyams

79 p., ill.

Moravian Falls, N. C.

Dixie Publishing Company,

1923

Call number CpB H193h (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- German

LC Subject Headings:

- Prisoners of war -- United States -- Biography.

- Soldiers -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Soldiers -- United States -- Biography.

- World War, 1914-1918 -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Hallyburton, Edgar M., b. 1890.

- Prisoners of war -- Germany -- Biography.

- United States. Army. Infantry Regiment, 16th. Company F.

- World War, 1914-1918 -- Prisoners and prisons, German.

Revision History:

- 2002-04-25,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2002-03-15,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2002-03-14,

Leslie Sult

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2002-01-25,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Verso Image]

SERGEANT HALLYBURTON,

THE FIRST AMERICAN SOLDIER

CAPTURED IN THE WORLD WAR

BY

CHAS. W. HYAMS.

PRICE $1.00

DIXIE PUBLISHING COMPANY,

MORAVIAN FALLS, N. C.

1923

Page 2

COPYRIGHT, 1923

BY GEORGE B. HALLYBURTON.

Page 3

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I.

BOYHOOD DAYS . . . . . 9 - CHAPTER II.

SOLDIER IN AMERICA . . . . . 15 - CHAPTER III.

IN FRANCE WITH PERSHING . . . . . 24 - CHAPTER IV.

INTERESTING MATTERS . . . . . 36 - CHAPTER V.

BACK HOME . . . . . 47 - CHAPTER VI.

PRIVATE FRANK C. HALLYBURTON . . . . . 71

Page 5

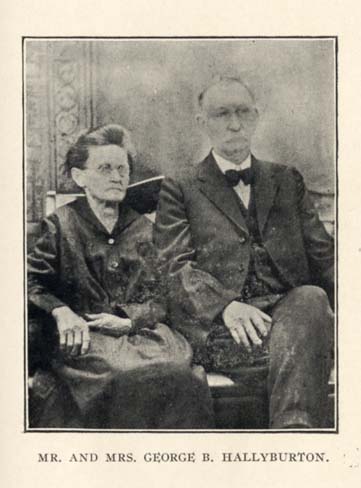

DEDICATED

To the patriotic father, who never had a feeling of fear, and the venerable mother who placed her trust in God, when two of their sons were called upon to risk their lives "for the peace of the world," with a feeling of pleasure, pride, and admiration, we gladly dedicate this little volume, believing it will prove a solace to them during their declining years.

THE AUTHOR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author desires to extend his sincere thanks to Miss Grace I. Gish of Roanoke, Va., for much valuable aid in the preparation of this little volume.

Page 8

SERGEANT EDGAR M. HALLYBURTON.

Page 9

CHAPTER I.

BOYHOOD DAYS.

SERGEANT Edgar M. Hallyburton, the first American soldier captured in the World War, is a son of Mr. George B. Hallyburton and Mrs. Prudence Hallyburton. He was born in Iredell County, North Carolina, January 19, 1890, just 27 years, 9 months, and 14 days before he was captured, but not conquered, by the blood-maddened hosts of an infuriated Kaiser. Even while a mere lad it was characteristic of him to take the lead, and almost invariably to excel in the games and sports peculiar to that period of life. He was always a favorite with his playmates, and this was due largely to his wit, humor, keen sense of right and wrong, courtesy, kindness, justice and impartiality. He enjoyed the privileges and blessings of a typical Southern country home where each child is taught from infancy to speak the truth, be strictly honest, bold, brave, fearless in the face of threatened or imaginary danger, obey their parents in all things, at all times, in all places, and under all circumstances, to love their native land, and revere the Almighty. Young Hallyburton is of Scotch-Irish decent and

Page 10

this, no doubt, accounts for the fact that even as a boy he was full-sized, well-built, open-faced, with heavy brows and brilliant eyes. Having spent all his young days on the farm, naturally he was rugged, healthy, resolute, and of a friendly disposition. He was an unusually accurate shot with a gun, and when only ten years of age, was awarded first prize for being the surest shot in the neighborhood. It might truthfully be said of him that he idolized a gun from the hour that he was first old and strong enough to hold one in his arms, and this fascination for fire-arms was prophetic of his successful and wonderful career as a soldier later on in life which will be seen by a further perusal of the history of his career as a soldier. As a marksman, this young soldier in the making, seldom missed a shot, and it made no material difference to him how fleet-footed the rabbit or squirrel might be, or how swift winged the quail might soar, their greatest speed simply meant death if they came within range of his trusted gun. We are writing at some length about his attachment for his gun because it may well be called a vital thing in his life, and he carried it with him wherever his parents would permit him, and with Edgar it was a means to an end, and that end was the fascinating, romantic, and sometimes tragic story which is to follow. Many remarkable feats of marksmanship are told of him in the neighborhood where he was born and reared, but want

Page 11

of space forbids mentioning them, and we realize that our readers are more than anxious to learn about his romantic career as a soldier, fighting under the Stars and Stripes for Uncle Sam along the Mexican border and "Somewhere in France."

Owing to the active out-door life he lived, while a boy, we attribute his rapid development into a strong, robust man, with broad shoulders, expanded chest, and hardened muscles, well-fitted and qualified for the exacting duties of a soldier.

Before closing this chapter, it is but appropriate that a brief outline sketch of the home of our distinguished soldier be given. It was a substantial, modest, three-room cottage, situated a little back from the public road on a slightly rounded knoll with a rolling lawn shadowed by great hickories and giant oaks, and this was beautified by a hedge of blooming rose-bushes which completely surrounded the lawn. Two large grape-vines, full of luscious fruit might be seen at each corner of the house which trailed up over the windows and formed an awning of ample, cooling shade over the door. Here we find the old-time smokehouse made of logs, full of hams, shoulders, middlings, and other good things to eat. As is quite common in this section of the country, we must go down a slight hill before we find the shaded spring and springhouse. This little home of ice-cold butter and milk is made of logs and covered with clap-boards, floored

Page 12

with white sand through which a small stream of icy water flows, and in this channel we find crooks of delicious milk, jars of luscious cream, and bowls of wholesome butter, all appetizing and good enough to adorn the table of a king, and satisfy the appetite of a queen. It can be truthfully said of Sergeant Hallyburton that whether as a boy, a young man, a civilian, or soldier, he always wore the white flower of a gentleman, and no one has ever become acquainted with him but what they learned to admire him for his sterling traits of character.

Sergeant Hallyburton received his education at the Stony Point High School, from which he graduated with honors. The high esteem in which he was held by teachers as well as schoolmates is attested by the fine tribute from the pen of the principal, which occurs on another page. During his school days, Sergeant Hallyburton was chosen captain of the football and baseball teams of his Alma Mater, and he was a leader in the literary societies over which he often presided, and his splendid voice was frequently heard in the debates which took place on numerous occasions. One of his school-mates remarked a few days ago that so far as his courage went, young Hallyburton might well have been called "the bravest of the brave," always to be found championing the cause of right, and defending the weak against the strong in those

Page 13

fist-cuffs peculiar to boyhood. Even in his younger days Young Hallyburton was always courteous and ever ready to defend the opposite sex. He always showed profound respect for old age and no time was time too valuable or sacrifice too great for him to devote to those whose hair had been silvered by the frosts of Time. His youthful attachments for firearms undoubtedly forecasted his fame as a soldier while fighting under the Stars and Stripes. If he had his whole career to live over, I doubt if he would change it one iota. An unflinching and uncompromising friend himself he knew how to value the friendship which others gave him, and the fact that he made so few enemies (outside of Germany) is an honor of which anyone might well be proud. Always obedient to his parents from infancy, it naturally followed that he would obey orders coming from his superior officers, even though those orders carried him through the hell-holes called German Prison Camps. To the boy or young man who reads the history of Sergeant Hallyburton's life, it must prove an inspiration to lead him on to higher ideals and nobler purposes, fitting such a one (should the occasion arise for action) for a name and place high up on the temple shaft of Fame. Such a boy will see in the life of Sergeant Hallyburton how it is possible for even a ploughboy to reach to the highest pinnacle of Honor, and receive from the President of the

Page 14

United States, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, a Distinguished Service Medal, and from the highest officers in the army, letters of highest praise, loftiest commendation, and superior honor. Well may he be held up as a model for other boys and young men coming after him to follow, knowing that each and every effort they put forth while following in his footsteps will be crowned with success, and handed down to future generations to lavish praise upon. Surely he is a model well worth imitating.

At the outbreak of the war, the Hallyburton family consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Hallyburton, two daughters, Misses Lola and May, four sons, Edgar, Elbert, Frank, and William. At this writing, Sergeant Hallyburton's parents are living quietly at Taylorsville, North Carolina, enjoying the rest they have so deservedly earned.

Page 15

CHAPTER II.

SOLDIER IN AMERICA.

EDGAR M. Hallyburton enlisted when only 19½ years old in the Regular Army, July 4, 1909. He was sent to the Coast Artillery at Fortress Monroe where he remained for about two years. He was then transferred to Galveston, Tex., where he remained about six months. He then returned to Fortress Monroe, and remained there until the close of his first enlistment, when he re-enlisted, and was sent to San Francisco, where he was placed in the Infantry. He remained there about a year, and then was sent to the border at El Paso, Texas, where he remained until the close of his second enlistment. After a stay of one month at home, he returned to El Paso, and enlisted in Company F, 16th Infantry. Just a short while after this, President Wilson, as Commander-in-Chief of the American Army, ordered General Pershing to form a flying squadron composed of his bravest soldiers and to proceed to the Mexican border for the purpose of capturing Villa and his followers. In carrying out this order, Young Hallyburton, then a private, was one of the first

Page 16

to be called and elevated to rank of Sergeant. Acting upon orders from his commanding officer, Sergeant Hallyburton, with his scouts, mounted on fleet-footed army horses, proceeded to cross the Rio Grande, which is the border-line between the United States and Mexico. Once upon Mexican soil, both scouts and steeds found the sky clear, the air still, and the sun hot. Both scouts and steeds were covered with dust. The latter snorted as it formed like icicles on their noses. All grew thirsty--a thirstiness that was all the more acute because there was no water in sight--not so much as a place that looked as if there might be water. A little after noon Sergeant Hallyburton, riding to the top of a lava mound, adjusted his field-glasses, and scanned the landscape. He discovered what seemed to be faint smoke rising from a string of hills about a mile away. Announcing his discovery, Hallyburton started on. Finally, arriving on the brow of the hills, he looked down on a cliff-walled valley in which he saw a primitive Mexican village. In the center of this village, the bake-oven of medieval pattern was sending up a feeble smoke. Slipping down a burro and goat path into the village, they found the Mexicans, men, women, and children. Sergeant Hallyburton asked them about water for the horses, and in answer, one rose and walked out telling him in broken English that he might have a few bucketfuls that came out of a

Page 17

common barrel. The Sergeant told them to give the horses all they would drink. In a few minutes the horses were ravenously eating, coffee was simmering on the fire, and tin cups and plates rattling. Sergeant Hallyburton studied the Mexican situation and became convinced that rural Mexico lived largely independent of the market. Their dirt houses were small and tight, hence needed but little fuel to keep them warm through the winters. Burros and goats lived the year around on wild grasses and brush, hence saved the expence of providing food and shelter. In conversation with one of the men who could make himself understood in English, the Sergeant learned that they were all friends of Villa upon whom they looked as their Moses. By three o'clock the horses were in silent rest, and the scouts lying on the ground. But a call from the Sergeant brought them all to their feet. All filed across the valley--some of them as if they would never stop. Coming up out of the valley, they reached the open plateau, and continued west until the sun was sinking, and it was time for them to turn in for the night. Darkness prevented them from seeing their way, and their horses weary from long travel, they found a clump of cedars a short distance away and under these they wrapped themselves in their blankets and went to sleep on the ground. Next morning when they awoke half-frozen and hungry, they mounted their

Page 18

horses and resumed their journey, vainly looking for a village where they could get food and water, but none was in sight. But they did see a lonely maverick grazing side-deep in the sage brush, which they proceeded to kill with a shot from one of their rifles. They soon dressed and cooked their prize, and in a few minutes the fragrance of broiling beef steak was filling the desert air. When their one-course breakfast was over, they went on through the increasing heat and dust. The previous days' sameness was broken only by hills and gorges. On and on they went, deeper into the wild. Everything in the wild was perfectly motionless and silent. By this time the horses were fairly reeling, with watering eyes and swollen tongues. Starting down the gorge to find a slower grade out, every horse listened intently, then lunged down the grade champing and frothing. Soon they came upon a little water-mill, beyond which, in a cottonwood grove, stretched a typical Mexican village. Switched from the smell to the sight of water, the horses lunged on down, and soused their noses into the creek. In the meantime, Sergeant Hallyburton dismounted, and handed his rein to a comrade, then he walked up into the little mill house. Right away the mill slowed down to a stop, and the water roared more loudly over the dam. Soon he and the old miller came out, and proceeding down the path to the foot-log, joined the horsemen, and all

Page 19

went up Main street--an alley through burros, goats, geese, and ducks--into a corral of adobe. Amid great neighing and whinnying, they gave their horses great armfuls of corn and alfalfa hay. They now awaited dinner on the miller's lawn. This gave Sergeant Hallyburton an opportunity to study Mexican country life on a much broader scale than he had done before. Not long afterward the old miller came out and invited them into his whitewashed adobe house and seated them around the makeshift table. When dinner was over, they returned to seats on the lawn. The horses now having rested, the men saddled them and disappeared, going out a wood road through an unknown country in a vain and fruitless search for Villa. After many days and nights of wearisome traveling over rugged hills, across malarial streams, and uncultivated valleys, still failing to see or hear anything of a reliable nature as to the where-abouts of the notorious Villa, Sergeant Hallyburton and trusted scouts, worn out in body and mind, finally returned to camp, and reported their failure to General Pershing. Shortly after the occurences enumerated above, Sergeant Hallyburton and his squad, in company with a large number of other soldiers, were transferred to El Paso Tex., to guard the city. From this point they were soon sent back to the states, eventually to sail with the first contingent of the American

Page 20

Expeditionary Forces under General Pershing to France, there to fight for the peace of the world. It is not necessary or appropriate that the causes which led up to America's entrance into the World War be stated in our sketch of Sergeant Hallyburton. This duty properly belongs to the pen of some other historian, and to that one we leave it, knowing that it will be written by impartial pens.

Through all the years of his service as a soldier, whether "a private in the rear rank" or as an officer, Sergeant Hallyburton was spoken of by all his comrades as eager and unafraid. He was one of the great brotherhood in uniform with the fighting password "All for one and one for all." He shared their pains and privations, their adventures in front lines and in rest places, and they knew him with the knowledge that men have when, as a matter of course, they face death together. He was known to all America, in whose cause he fought with impassioned impulse. It might well be said of him that he is the man called Million, upon whose broad shoulders rests the rule of the Government. He was the significant symbol of the rear rank private and the commanding officer who made victory possible. His jubilant antagonism overthrew the aged power of Prussia, and the joyful alacrity with which he went to battle, overwhelmed the Empire which had staked its life on the ancient law of the jungles. He always fought

Page 21

with a great hope stirring in his heart. He was assured that he would battle in the war against war; that his steadfast service would help make the world of the future safe for democracy. He knew that the overthrow of the divine right lord of war would make of mankind something better than cannon fodder, and the world a better place in which to live and love. He relied upon these principles, and scorned the muddled motives and subtle sophistries of those with sinister interests to serve. He gladly gave his best to prove his devotion to this holy cause, the highest and best cause the mind of man can conceive--the common good of the world. In the World War, Sergeant Hallyburton knew nothing, perhaps, of dogma, but he knew his duty, and performed it to the uttermost whether on the quiet tented fields at home or facing the fearful crash of shot and shell on a foreign battle-line. He may not have been familiar with creeds, but he had an unsurpassed courage in deadly danger. He was not a student of doctrines, but he was steadfast in devotion to his Flag, the symbol of all the noble ideals he knew. He could not define sanctification, perhaps, but he could define service by living it in camp and field of battle. He could not express his inner being in words, perhaps, but he could prove their nobility with his works. He could not orate lip praises of righteousness, but he could give, and would have given his

Page 22

life for it in a turbulent and terrible time. He had that faith which oversweeps all fears and leaves one satisfied.

Wherever patriotism is valued, wherever valor is admired, and wherever the English language is spoken, the name and fame of our hero will be mentioned in burning words of eloquence, and as Time grows older, and unborn generations come upon the field of action, men, women, and children will read, and learn, and speak of Sergeant Hallyburton and the unmatched courage and unsurpassed valor which characterized every act of his life while a soldier of the United States, whether at home in time of peace or on the shell-torn battlefields of a foreign land where he fought so valiantly for the peace of the world, and that democracy should not perish from the hearts and minds of men of all nationalities. Surely, at the last, this patriotic soldier, faithful at all times and under all circumstances, secure in his own cause, in a sudden gleam of insight, will know and understand the immortal hope which lights the warriors way from dark to Deity. He was in no sense an unknown soldier, but one known to father and mother, to comrades, officers, to Country, and to God. His final resting place, when Death shall touch his heart, will be a "pillar of cloud by day, and a pillar of fire by night" to guide America along the Golden Rule pathway to the promised land of enduring

Page 23

peace. His name shall sound like the call of a trumpet; the name of one who fought that the world might live in peace, the first American soldier "captured but not conquered" in the World War.

Page 24

CHAPTER III.

IN FRANCE WITH PERSHING.

EDGAR M. Hallyburton was promoted from a private to a Sergeant while in Mexico with General Pershing, and retained that position while in France. He sailed for France with the First Division, Co. F, 16th Infantry. Immediately upon the arrival of the First Division upon French soil, it was put to work in the trenches. It may prove interesting to give a brief sketch of trench life. On account of the trying work in the trenches, frequent changing of men is customary, when possible. Usually they were marched out of the trenches in the dark, their feet wet and muddy clothes clinging to them. From a military standpoint, the experience gained by the Americans is considered of a very high value. The First Division had only two clear days while in the trenches. When they left the trenches they were mud from their hats to their shoes. Before anything else, they required a bath, first with gasoline and then water. With the men back in billets, it is now permitted to mention for the first time (says a

Page 25

dispatch) that the casualties were negligible. In fact more men suffered with "trench feet" than with wounds. "Trench feet" means that the feet become swollen and sore from standing in mud and water in the trenches. Officers commented on the remarkably small amount of sickness which developed. There were some who had colds, but as far as reported, there were less than half a dozen cases, including "trench feet" and pneumonia. An officer said the splendid physical condition of the men was responsible for this showing.

The men who served in the trenches tell interesting stories of their experiences. On clear days especially, German snipers became active. Bullets went singing harmlessly overhead. American infantrymen were told oft to attend any sniper who became active, and more than one of them will snipe Americans no more. This game of sniping the sniper was very popular with our soldiers. The only complaint usually heard was that there was not enough snipe-shooting to satisfy the infantrymen. Plenty of "our boys" say they went out to snipe, but did not get enough. Immediately after this trench training, our hero with a small detatchment was sent to a sector of the first-line trenches. It was at this point where Sergeant Hallyburton and his squad were located that the German artillery dropped a heavy barrage fire which completely isolated them from help.

Page 26

A dispatch under date of November 5th says: A small detatchment of American infantrymen was attacked in the front line trenches early Saturday morning, November 3rd by a much superior force of German shock troops. The Americans were cut off from relief by the heavy barrage in their rear. They fought gallantly until overwhelmed solely by numbers. The fighting in the trenches was hand-to-hand. It was brief and fierce in the extreme. As a result of the encounter, three Americans were killed, namely, Private Thos. F. Enright, Private Jas. B. Gresham, and Private Merle D. Hay, and four were wounded, these being Private Jno. J. Smith, Private Chas. J. Hopkins, Private Homer Givens, and Private Geo. I. Box. A sergeant, a corporal, and ten men were taken prisoners. Two French soldiers who were in the trenches, also were killed. The enemy lost some men, but the number is unknown, as their dead and wounded were carried off by the retiring Germans. From the beginning of the engagement to the end, the Americans lived up to all the traditions of the American army, the records showing the bravery of the detatchment, and of individual members. The German raid on the American trench was carried out against members of the second contingent entering the trenches for training. These men had only been in a few days. Before dawn Saturday, the Germans began shelling vigorously

Page 27

the barbed wire front of the trenches, dropping many high explosives of large calibre. A heavy artillery fire was then directed so as to cover all the adjacent territory, including the passage leading up to the trenches, thereby forming a most effective barrage in the rear as well as in the front. The young lieutenant in charge of the attachment of Americans started back to the communicating trenches to his immediate superior for orders. The barrage knocked him down, but he picked himself up and started off again. He was knocked down a second time, but, determined to reach his objective, got up again. A third time he was knocked down, badly shell-shocked, and put out of action.

Soon after that, Germans to the number, according to the report, of 210 rushed through the breaches and wire entanglements on each side of the salient, their general objective barrage in the forefield having lifted for a moment. The Germans went into the trenches at several points. They met with stout resistance. Pistols, grenades, knives, and bayonets were freely used.

For many minutes there was considerable confusion in the trenches, the Germans stalking the Americans, and the Americans stalking the Germans. In one section of the trench, an American private engaged two Germans with the bayonet. That was the last seen of him until after the raid, when a dead American was found on the spot.

Page 28

Another was killed by a blow on the head with a rifle butt from above.

Some of the Americans, apparently at the beginning of the attack, did not realize just what was going on. One of the wounded, a private, said, "I was standing in a communicating trench, waiting orders. I heard a noise back of me, and looked around in time to see a German fire a gun in my direction. I felt a bullet hit my arm."

The Germans left the trench as soon as possible, taking their dead and wounded with them. An inspection showed, however, that they had abandoned three rifles and a number of knives and helmets.

The raid was evidently carefully planned, and American officers admit that it was well executed. As a raid, however, there was nothing unusual about it. It was such as was happening all along the line. There is reason to believe that the Germans were greatly surprised when they found the Americans in the trenches instead of the French.

The French general in command of the division of which the American detatchment formed a part, expressed extreme satisfaction at the action of the Americans, for they fought bravely against a numerically superior enemy, the handfull of men fighting until they were smothered.

The officer who had charge of verifying the accounts of this raid says, "I am proud to say that

Page 29

our men engaged in the fight did everything within their power. They jumped into the fight and stuck to it. In the first place, the troops had been in the trenches less than three hours when the barrage of the Germans began. They had marched a good part of the previous night and were tired. Some of them were allowed to go to sleep in a dugout 25 feet under ground. When the barrage began, these men did not hear the racket. It is apparent that the first they knew of it was when the Germans started throwing grenades down upon them. It was these men who were taken prisoner, but they fought well, even when surprised that way, for the dugout was covered with blood, especially the top half, showing that the Germans there must have been hit. The entrance to the dugout also gave indications of close hand-to-hand fighting.

"From the dugout through the trenches and over the top through the barbed wire and well into No Man's Land there was a wide, red trail. How much of it was American and how much German blood is not known."

It was during this raid that our hero, Sergeant Hallyburton, was the first American soldier to be captured, but never conquered, by the Germans. After his capture, Sergeant Hallyburton was sent to various prison camps in Germany. The treatment that he and his companions received at the hands of their captors is enough to make the blood

Page 30

of any true American boil with undying and eternal hatred for the German officers. Sergeant Hallyburton summed up in a few words the kind of food they received. "It was nothing more than slop. We would have fed it to the hogs at home. I passed seven months at Tuchel. It was a strafe camp and a hell-hole in every sense of the word. We were hitched to a wagon like horses and forced to draw wood fourteen kilometers (about seven miles) all day long. Dirty German guards were constantly insulting us at the point of bayonets. We wore wooden shoes, and for socks we used a winding fabric and paper. Scantily clothed and half-starved, we pulled our wagons through snow last winter that was about to our knees. There were eighteen Americans in Tuchel. I had written Post Cards to the Red Cross from each town we had been in previously, but they could never have been sent, for no answer was received until four months after we reached Tuchel. It was then (March 12, 1918) that the first Red Cross parcels arrived. These parcels saved our lives. If we had been forced to continue two months longer on the prison food and under the harsh treatment, I am certain most of us would have died of starvation."

Sergeant Hallyburton and his companions were transferred to Rastadt on August 14, 1918. There were about 500 American prisoners in the

Page 31

camp at that date. When Sergeant Hallyburton and his companions first reached Rastadt, they organized and demanded that the Sergeant be given command over all the American prisoners. They were so persistent that the Prussian general gave his consent. At this point they also decided to demand better treatment. They had noticed that the Germans had a distinct treatment for prisoners of each nationality. Russians and Roumanians were treated like dogs, or worse, and were being slowly starved. British were treated somewhat better, and the French best of all. Americans were new in Germany, and no standard of treatment had been established for them. The Germans had started the Americans on the same plan as the Russians. Hallyburton and his comrades began establishing an American standard. They made him leader, and agreed to stick by him in anything. They summed up their position thus: "We'll soon die on this anyway; we should have died at the front, and we can't die better than by demanding that we be treated as Americans."

Hallyburton first ordered them to clean up as best they could, then he demanded in the best military way, to see the camp commander. He saw him, and declared that the Americans must be treated better, and refused for them to do further wood-hauling. He told the Prussian he could either line the Americans up and shoot them or

Page 32

comply with their demands. The commander was furious, but the Americans hauled no more wood. They were moved to Rastadt, and their food improved, Red Cross packages arrived and were distributed evenly. Ultimatums and demands were made in a soldierly way, with increasing force as the Americans established their standing. The Americans were careful to be diplomatic and just in their demands.

Their camp became a model. Hallyburton had a commander of each barracks to see that every American kept his clothes cleaned and his shoes blacked. Every salute had to be snappy and correct. The Americans gained a special barracks by demanding them. Under Hallyburton's orders, these were cleaned twice a day. They were better than those of the German guards.

Then came the fight against German propaganda. They were publishing a paper in Berlin called "America in Europe." It was distributed in the prisons and over American lines. The sheet was written by Germans who had lived many years in America and who could use American slang. When the first issue appeared, the editor came to Rastadt, and interviewed Hallyburton, representing himself as appointed to look after Americans because of his sympathies for them. He was told the paper would be welcome if it would cut out the propaganda and print sporting news.

Page 33

This was agreed to by the "friend of Americans."

Next week he appeared with the new issue somewhat revised to suit the Americans. The German's clumsy efforts were amusing, but Hallyburton saw danger in the propaganda still in the paper. He forbade its circulation among those under his command. For this our hero was taken to a punishment camp. His stay was short. The Germans placed an incapable American in charge of the Rastadt camp, who immediately muddled affairs. The several hundred prisoners struck, and insisted that Hallyburton be returned. The German commander complied with the request.

On his return, Hallyburton was called up before General Von Kalteureit, the hard-hearted old Prussian in charge of prisoners. Several hundred new Americans had been gathered at Rastadt, and the general granted Hallyburton charge over them, leaving the old group under the incapable substitute. Hallyburton refused, but offered to take charge of the entire camp. The old Prussian argued, but ended with, "

influence them to write letters saying they had not been mistreated. Some letters were too favorable to the Germans, so Hallyburton established a censorship pen. He knew the Germans were waiting for favorable letters to publish. Another battle against propaganda was against an individual named Enders, who claimed to be American, and the correspondent of an American news agency. He appeared several times at the camp saying he was gathering data to prove that Americans were not mistreated in Germany, and that he had been "permitted" to do so by the German government. Hallyburton told Enders he had better leave camp before some of the "dough-boys" "insulted your German friends by telling the truth." Enders left, and never returned for more data. When the armistice was signed, the German guards suddenly left the camps. Those who remained were lenient, and told the Americans that prisoners were free to go to towns and do as they pleased. Hallyburton saw danger in this, if the men became mixed up in revolutionary measures. It would also further complicate their food arrangements with the Red Cross, and so orders were issued for every man to stay in camp and do his work. By this time each man had been assigned to some sort of work for which he was adapted. There were tailors, shoe-makers, barbers, cooks,

and practically every type of industry needed in camp, including a staff for the camp paper, which was copied by hand, cartoons included, and posted for reading. The order was difficult for many men to understand, but it was adhered to by practically every one. Next came the organization of trainloads of men to leave for France. One by one these problems were met, and the soldiers were assisted by Red Cross men who arrived from Switzerland. The Red Cross men were amazed at the organization the doughboys had accomplished in every camp, and found the native population in districts around the American prison camps full of admiration for the way our boys had handled themselves under difficulties and without authority. The reader will find numerous citations from various sources describing in detail the experiences of Sergeant Hallyburton before and during his captivity. As will be seen further on, Sergeant Hallyburton lost no time after the armistice was signed before he left that blood-soaked and devastated land for the peaceful and happy home of the pure and the brave.

SERGEANT Hallyburton's first letter home reads as follows:

Darmstadt, Germany, "Dear Father:

Page 34

Page 35

Page 36CHAPTER IV.

INTERESTING MATTERS.

December 31, 1917.

"Will write you a few lines. I am well and all right.

"Write the First National Bank of El Paso, Texas, and tell them to put my money on interest in savings department until they hear from me.

"I will see you after the war is over. Tell Jim and Mae to write me. Also Bub.

"Also tell the bank I am here and don't know when I will get back, but to put all my deposits to my credit on savings, and give them my address and tell them to send me a statement of balance.

"Well, I will close for this time, and will write you again soon.

"With love to all,

"Your son,

"Edgar M. Hallyburton,

"20th Company, 5th Battalion,

"Darmstadt, Germany."

Page 37

While at Tuchel, West Prussia, Sergeant Hallyburton on June 10, 1918, wrote his father a short message on a post card used by prisoners of war, as follows:

"Dear Father:

"Am well and getting on fine.

"I receive mail from you regular, and write you once every week. Do you hear from me regular? Will close for this time, hoping to hear from you soon.

"With love,

"Your son."

GERMANS TAUNT US.

The news comes from Berlin that the German news-papers "played up" in headlines the capture of the American soldiers; one news-paper, the "Lokal Anzeiger", published in Berlin, under the caption of "Good morning, boys," the following:

"Three cheers for the Americans! Clever chaps they are, it cannot be denied. Scarcely have they touched the soil of this putrified Europe when they are already forcing their way into Germany. Before long they will cross the Rhine, and also enter our fortresses. That is express-train speed and American smartness.

"It is our good fortune that we are equipped to receive and entertain numerous guests, and that

Page 38

we shall be able to provide quarters for these gentlemen. However, we cannot promise them doughnuts and jam, to this extent they will be forced to recede from their former standard of living. They probably will become reconciled to this, for soldiering is a very risky business. Above all, they will find comfort in the thought that they are rendering their almighty President, Mr. Wilson, valuable services, inasmuch as it is asserted he is anxious to obtain reliable information concerning conditions and sentiments in belligerent countries. In this way he will obtain first-hand information about things in Germany.

"As Americans are always accustomed to travel in luxury and comfort, we assume that these advance arrivals merely represent couriers for larger numbers to follow. We are sure the latter will also come and be gathered in by us. At home they believe they possess the biggest and most colossal everything, but such establishments as we have here, they have not seen.

"Look here, my boys! Here is the big firm of Hindenburg & Co., with which you want to compete. Look at its accomplishments, and consider whether it would be better to haul down your sign and engage in some other line. Perhaps your boss, Wilson, will reconsider his newest line of business before we grab more of his young people."

The above bit of news was no doubt edifying

Page 39

to our boys, and clearly showed them how dense was the fatal ignorance of the German government so far as its knowledge of the wonderful part America and American soldiers were to perform in the great World War. An ignorance which was not only inexcusable but fatal to the hopes, aims, and aspirations of the Kaiser and his horde of infuriated and war-maddened followers who knew nothing but what had been told them, by their superior officers, concerning America, which was then the greatest country on earth and the one to crush Germany.

RED CROSS SENDS FOOD.

In the issue of May 1st, Red Cross Briefs, the bulletin of the Southern Red Cross Division, published three times a month at Atlanta, there was an item with regard to food for American prisoners. "Prisoners arriving in German camps should find Red Cross emergency food parcels awaiting them, if arrangements are carried out. The Red Cross has secured permission to store emergency supplies at the prison camp at Tuchel, West Prussia. Three hundred and sixty ten-pound parcels have been shipped there for the relief of American prisoners newly arrived from the front. Sergeant Hallyburton and Corporal Upton, American prisoners, have been delegated custodians of the emergency food supplies and a store room has been assigned to them in which to keep the parcels that have been

Page 40

forwarded, says a cable from the Red Cross headquarters at Berne, Switzerland."

DALLIN'S STATUETTE.

The soldier whose picture, after he had been captured by the Germans during the first successful raid on the American lines, served as the guide for Cyrus E. Dallin, the sculptor, in the production of his statutte, "Captured But Not Conquered," which was used to help the third Liberty Loan campaign, has been authoritatively identified. It was at first thought that the picture, which had been sent out by the Huns to show that they really had taken a few Americans, was that of Sergeant Leith of Schenectady, N. Y., and was so announced officially from Washington. Later, however, a brother of Leith received a letter from him saying that he had not been made captive. Now it turns out the man is Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton, son of Mr. Geo. B. Hallyburton and Mrs. Prudence Hallyburton of Stony Point, N. C., who had served nearly ten years in the army.

The first intimation that the statuette had been modelled from Hallyburton's picture came to Mr. Dallin in a letter from Charles O. Carrier, in which he says: "Having seen a reproduction of your statuette 'Captured But Not Conquered', I wish to pay you a compliment, but am at loss for words. With the original of the photograph, I am personally acquainted, and you have not only reproduced

Page 41

the features and expression, but his actual character is embodied in the same. I thought perhaps you would be pleased to learn his name which is Edgar M. Hallyburton, son of Mrs. Prudence Hallyburton of Stony Point, N. C., to whom I have mailed a copy."

This letter finally reached Mr. Dallin at Springville, Utah, and he submitted it to Mr. John K. Allen, publicity director of the Liberty Loans in New England.

"Our use of the statuette", said Mr. Allen, in a letter to the sculptor, "struck a high note in publicity, and those which were sent to the various cities in New England have found their way either into the public libraries or art museums, and the New England Liberty Loan Committee has received appreciative letters acknowledging their receipt." Mr. Allen also informed the scculptor that he had authorized the New York Liberty Loan Committee to make use of the statue in its next drive.

On June 26th, Mr. Allen wrote Mrs. Hallyburton as follows:

"Chas. O. Carrier of Irving, Ill., has written to Mr. Cyrus E. Dallin stating that the original of his statuette, "Captured But Not Conquered", is your son, Edgar M. Hallyburton. When the reproduction of the picture, originally published in the German illustrated papers, was produced in the American newspapers, the soldier was identified as

Page 42

Sergeant Leith of Schenectaday, N. Y., Later we found the identification was inaccurate, as a letter was received from Sergeant Leith to his brother, stating that he had not been captured. It is very desirable that we establish the identity of the subject of this statuette. It played an important part in the Third Liberty Loan Campaign in New England. Will you have the kindness to write me if the young man is your son, and I will be happy if you can send a photograph of him which I can place beside the statuette which is now on my desk. I trust that I am not asking too much of you, and that you will co-operate with us in this important historical incident."

Mrs. Hallyburton replied as follows:

"We are glad to answer your letter. Sergeant Hallyburton is our son, and was captured on November 3, 1917, in the first fight for World Liberty. We would be glad to know more about the statuette. We would like a copy of it. We are glad to know that our son has in any way helped in the Liberty Loan. Please give us the details. We are sending, as you requested, his photograph. It is the only kind we have, and it has been taken sometime, as he has been in the service nine years. He is now 28 years old, and joined the army at nineteen and one-half years old. We would be glad to hear from you again, and will be of any service we can."

Page 43

SEES STATUETTE OF HIMSELF.

Visitors to Governor Cornwell's office noticed on his desk a three foot statuette of an American soldier, done in plaster paris, a rather striking figure. It shows a Sergeant in an American uniform, with right hand in his pocket, his left hand clenched, while his jaws are set, and a bull-dog expression on his face. On the base of the statuette are the words "Captured But Not Conquered."

The governor had had to explain to innumerable visitors that it was presented to him by John J. Slipper, who purchased it in Boston during the last Liberty Loan Campaign; that it represented Sergeant Hallyburton whose home was at Stony Point, N. C., and who belonged to the regular army in the first division to go abroad; that fate decreed that he should be the first American captured.

On Monday, there came into the Governor's office, Major Coulter and Colonel Ryder of the First Division, who were in Charleston with the regular troops now stationed there. Major Coulter glanced at the statuette, and said to the Governor, "That face looks familiar. Who is that?" The Governor replied that it was the first American that the Germans captured.

"Why, yes, that is Sergeant Hallyburton of the 16th Company. He is right here in town."

The governor asked that he be brought in,

Page 44

whereupon Major Coulter took up the telephone, communicated with headquarters, and made arrangements for Sergeant Hallyburton to come up to the governor's office at ten o'clock Tuesday morning to meet the governor, and to see himself in a plaster of paris statuette.

Governor Cornwell had been asked many times whether that first American prisoner came out of the war, and was never able to answer the question until that Monday afternoon when he learned from the officers referred to that the Germans put Hallyburton in charge of the American prisoners in a large camp in Germany. There were a number of American officers among the prisoners, but Hallyburton had absolute command, and ruled with an iron hand. After the armistice, he was in command of a large hospital at Toul. This hero who was "Captured But Not Conquered" had been walking the streets of Charleston for days.

RECEPTION TO GENERAL WOOD.

Following his return from Kanawha City, where at 9:30 o'clock he conferred the distinguished service cross upon a member of the First Division, General Leonard Wood and his staff were tendered a reception in Gov. Cornwell's office at which many of the state and city officials and other prominent citizens of the city were made acquainted with them. With the general, were Col. C. B. Baker, Capt.

Page 45

J. B. Campbell, the general's son, and his aide, Lieutenant Osborne C. Ward.

James W. Weir, Gov. Cornwell's secretary, made an effort to get as many of the state and city officials present as possible. They included State Auditor, John S. Dart, Secretary of State, Houston G. Young, State Treasurer, Wm. S. Johnson, Attorney General, E. T. England, Superintendent of Schools, M. P. Shawkey, Commissioner of Agriculture, Jas. H. Stewart, Judge E. F. Morgan of the public service commission, former State Senator, W. P. Hawley, Mayor Grant P. Hall, Walter E. Clark, proprietor of the Charleston Mail, Jesse V. Sullivan, former secretary of the state council of defence, J. G. Bradley, Pres. of the W. Va. Coal Association, and a number of others.

Decidedly the most interesting incident of the impromptu reception was the presentation of Sergeant Hallyburton, of the 16th Infantry, to Gen. Wood.

As the sergeant entered the presence of Gen. Wood and his staff this morning, he presented a fine picture of a soldier. Extending his hand in greeting, General Wood advanced a step to meet him, and Sergeant Hallyburton, bringing his heels smartly together in soldierly fashion and standing straight as an arrow, shook hands with the general.

Sergeant Hallyburton is about six feet tall, is

Page 46

well proportioned physically, without an ounce of superfluous flesh, and is of the "lean" type of soldier whose countenance shows plainly the value of his experience in the war.

General Wood asked the sergeant many questions, and Hallyburton answered modestly, giving a very brief recital of his life as a captive in a German prison camp.

"How did you get along when the Boches tried to get information out of you," asked the general. "Treated pretty badly?"

"That was a pretty hard matter," replied Hallyburton. "They used us pretty badly for a while, but when they found they couldn't break our spirit, they let up a little. They seemed to want information about aeroplanes more than they did about America's purpose in the war. They did ask me whether America was in the war in earnest, and whether many troops were to be sent, but I told them I had not been in the States for sometime, and really had no information on that point."

"That was the best way out of it," commented General Wood.

Hallyburton explained in answer to the questions of the general how he, with ten other soldiers, happened to be captured, and in reply to another query, said his imprisonment lasted from November 1917 to December 1918.

Page 46a

MR. AND MRS. GEORGE B. HALLYBURTON.

Page 47

CHAPTER V.

BACK HOME.

SERGEANT Hallyburton lost no time after his release as a prisoner of war behind the German lines before setting sail for America. He landed at Camp Mills, Long Island, and soon secured a sixty-day furlough, and left on the first train for "home sweet home" to see his parents, relatives, and friends. On his arrival at home, he found a letter from Adjunct-General Harris notifying him that he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal of which a detailed account is given elsewhere. This medal was sent to Camp Dix to be presented to Sergeant Hallyburton a few weeks later.

When the great crowd had assembled on the athletic field of the south parade grounds, Major-General Charles P. Summerall, after reading the letter from Adjunct-General Harris, said:

"This Distinguished Service Medal has never been more worthily bestowed than upon Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton. The records show that he is the only enlisted man to receive such a decoration in the World Far, and the First Division is proud

Page 48

of him as a comrade. His services, for which the grateful President of a grateful nation awarded this coveted decoration, showed that however restricted, whatever the limit of movement, a soldier and man may yet contribute to the glory of his country and to the honor of his army. He was taken a prisoner by the enemy in an honorable manner in a time of terrific danger known only to those who have experienced the test, and only by the narrowest margin escaped with his life. By his dominant personality, he compelled the enemy to treat humanly our American prisoners. By thus remaining faithful to his nation, even though in captivity, Sergeant Hallyburton strengthened the resolution of his comrades, and increased their buoyancy and fortitude."

The Division Commander thereupon pinned the decoration upon him, and congratulated him upon his good fortune. The 16th Infantry Band furnished the march, and played exceptionally well.

Not only before, but more especially after, his return to American soil, Sergeant Hallyburton was the happy recipient of all the praise and honor it was possible for a patriotic and patriot-admiring people to lavish upon him. This praise was spontaneous, out-spoken, unselfish, and unstinted. He had won it worthily.

It will not be out of place just here to give a few extracts from the news-papers to show how

Page 49

this praise was bestowed upon him while he was yet a prisoner of war within the German lines.

The Charlotte (N. C.) Observer mentions the following: "The war picture which is going the rounds of the papers as the 'first photograph to reach this country of Pershing's men in the hands of the Germans' was received with peculiar interest in the home of Mr. Geo. B. Hallyburton of Stony Point, Alexander County, for in the central figure in the picture,--that of the bare-headed soldier being questioned by German officers,--Mr. Hallyburton recognized his son, Sergeant Edgar Hallyburton. The protograph gave his parents the satisfaction of knowing that he is alive and not wounded, and they properly want their happiness given reflection through The Observer."

A FATHER'S TRIBUTE.

Mr. George B. Hallyburton, when he heard of his son's capture, in the simple, truthful language of his people, only said, "The German's didn't get Edgar without a fight, I'm sure; Ed is the fighting kind."

FROM HIS TEACHER.

"It can already be said of our boys, 'He hath done what he could', for after a heroic stand and desperate fight, Sergeant Hallyburton was captured by the Germans last fall. This band of boys, the first American prisoners taken during the war, is

Page 50

now in Darmstadt, Germany. Young Hallyburton's fine military record has won for him lasting honor, and given great impetus to the cause for which he was fighting, all over the country. We are justly proud of these boys, and feel sure our side must win when supported by such manly fellows as these."

"Armistice Day, or North Carolina in the World War", which is a book published by the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, in mentioning Sergeant Hallyburton says:

"It is a soldier's duty not only to fight in battle, but also to serve his country wherever he may be. This is what Edgar M. Hallyburton did. Edgar M. Hallyburton was born near Stony Point, Iredell County, North Carolina. He volunteered in the regular army and became a sergeant in the 16th Infantry. This regiment was a part of the First Division, and was one of the first regiments to go to France.

"In November, 1917, the Germans raided the American trenches and took Sergeant Hallyburton prisoner. Sergeant Hallyburton was carried into Germany and kept as a prisoner of war from November 1917 till November 1918. He was in many German prison camps and in none of them was he well treated. As the war went on, other American prisoners of war came to these camps. The Germans tried to break their spirits, and make

Page 51

them give valuable information about the American armies. They kept the American prisoners in dirty houses, and did not give them enough to eat.

"Many a soldier's spirit would have broken down had it not been for Sergeant Hallyburton. He organized the prisoners and found comfortable places for them to stay in. He saw that all food and clothing due them was fairly divided among all prisoners. He organized officers and made rules to prevent Americans from getting discouraged and giving Germans information about our armies.

"Finally, in November 1918, the Armistice was signed, and Sergeant Hallyburton and other prisoners of war were sent back to the American army. Here it was learned how he had served his country even while in prison. The government thanked him publicly for these fine services by giving him a medal called the Distinguished Service Medal. Many generals, colonels, and other men of high rank received this medal for fine work they did in training and leading soldiers. But none of them deserve more credit than Sergeant Hallyburton. He was not trying to win a name for himself. He was only doing his duty where he was. His was the spirit of service."

The following verses were used in the Fourth Liberty Loan campaign of New England:

Page 52

TO EDGAR M. HALLYBURTON

A prisoner of war in Germany.

By his Aunt, Mrs. Ella Lackey, Hamlet, N. C.

O, little boy, that used to roam

Among the peaceful hills of home,

With none of fear, so wild and free,

In dreams you often come to me.

These dimpled hands were my delight,

These fearless eyes were closed each night

In gentle slumbers; on my breast

This baby form was lulled to rest.

O, little boy that used to be;

O, captive son beyond the sea;

Who smoothes for you your prison bed?

Who pillows now your weary head?

Your soul is free! No prison bars

The spirit of the stripes and stars,

And those who stand for liberty

Will bring my soldier back to be.

BY H. E. C. BRYANT.

Washington, November 9.--The War Department issued this statement today:

"By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress, approved, July 9,

Page 53

1918, (Bulletin No. 43, War Department, 1918) a Distinguished Service Medal is awarded the following man: Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton, (42848) Company F, 16th Infantry. For exceptionally meritorious and conspicious services."

"Sergeant Hallyburton, while a prisoner in the hands of the German government from November, 1917 to November, 1918, voluntarily took command of the different camps in which he was located, and under difficult conditions, established administrative and personal quarters, organized the men into units, billited them systematically, established sanitary regulations, and made equitable distribution of supplies; he established an intelligence service to prevent our men giving information to the enemy, and prevented the enemy introducing propaganda. His patriotism and leadership under trying conditions were an inspiration to his fellow prisoners, and contributed greatly to the amelioration of their hardships."

FROM A SOLDIER'S RELATIVE.

A few days ago, a soldier's relative contributed to The New York Times a short letter of appreciation behind which there is a story of interest to the people of North Carolina. The Times' contributer wrote to this effect:

"Relatives of American soldiers detained in prison camps in Germany owe grateful thanks to

Page 54

Sergeant Hallyburton, president of the camp at Rastadt, Duchy of Baden, for his kind offices in endeavouring to acquaint anxious mothers, wives, and sweethearts of the whereabouts of their captured loved ones." It is then briefly related that in many cases no official record whatsoever gave the fate of the lads who had ceased writing, but by some method of his own, Sergeant Hallyburton managed to convey at least the information that they were alive in some place in Germany, which was relief of a sort. "As we cannot reach this excellent man and friend," the writer continues, "we relatives take this method of placing on record our gratitude to him and his efficient secretary, Corporal Geoghegan, who, in the midst of their own misery, could take thought of ours and attempt to mitigate it by at least a ray of hope. God bless them both, is our earnest wish."

HIS PICTURE.

The Associated Press dispatches carried the following article." "In the picture section of The New York Times of Sunday was a splendid picture of three American soldiers, taken prisoner by the Germans, being questioned by German officers. In addition to the group picture, the photograph of the three Americans was given separately. The photographs were obtained from German papers, passed by the British censor. The names of the prisoners did not appear, but acquaintances of

Page 55

Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton of Iredell County, North Carolina readily recognized his photograph,--the soldier with his hair brushed up in front. Sergeant Hallyburton was captured when the Germans raided the American trenches, November 3. These were the first Americans captured, and the Germans have made much of the event, apparently putting the captives on exhibition."

FROM EDITOR WADE HARRIS.

"The Observer's idea of an intertaining story is that which tells how Sergeant Hallyburton, the Alexander County boy (this should have been Iredell County boy--the Author) who was the first German captive, figured in the campaign of the Liberty Loan Committee of New England, which is presented elsewhere. The idea of the Committee itself should come in for first endorsement. It distinguished the North Carolina Sergeant by commemorating him in statuette. This art work was given display in the leading cities of New England with a placard reading: 'The first American soldier captured by the Germans. How long shall we allow him to remain a prisoner? Buy Liberty Bonds and set him free!' The statuettes and the appeal worked wonders in the success of the campaign, in New England, and for one, The Observer is proud of the distinctive part the Stony Point boy played in it. Incidentally, the story of the mistake in identity first committed by the New England

Page 56

committee, and how it was adjusted, adds to the human interest of the story. The Observer feels inclined to thank this Boston organization in behalf of the state for its signal contribution to the fame of Sergeant Hallyburton. It will be recalled that a few weeks ago a young man with a squint in his eye, and who had been rejected by the army for that reason, appeared in Charlotte and underwent an operation for the taking out of the squint. This young fellow was a brother of Sergeant Hallyburton, and he was determined to get to France 'to take Bud away from the Germans.' Possibly it may come to pass that the happy mother in the mountain home back in Stony Point may have a second statuette to adorn her mantlepiece, for the younger brother is quite sure to have a hand in the rescue of Sergeant Hallyburton, in case the rescue is accomplished."

PRAYER FOR SERGEANT HALLYBURTON.

The Charlotte (N. C.) News carried the following item just after the capture of Sergeant Hallyburton was made public:

"The General Synod of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church of the South, in late session at Fayetteville, Tenn., engaged in special prayer for Sergeant Hallyburton of Stony Point, this state, reported as being captured by the Germans in the first clash between the two lines. Sergeant Hallyburton is a "Seceder", a member of the Amity

Page 57

Church in Iredell County, and, therefore, a Psalmsinger."

Commenting on the above Associated Press dispatch, one of his home papers has this to say: "There is no way to tell, perhaps, nor will be, that the prayer of this body of consecrated ministers of the Gospel is ever answered for Sergeant Hallyburton. It is not allowed us to know whether or not a safe deliverance will come to him because of the supplications which have been sent up, but we have no doubt that if he could be made aware of the fact that back here in his home country he has been made a client of these pious ministers before the Courts of God, encouragement would come to his soul. Faced with the red waves of war's destruction, he is a fool who will not seek the side of heaven."

THE RED CROSS.

The American Red Cross today, February 8, paid Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton, whose home is at Stony Point, Alexander County, North Carolina, a handsome compliment by sending broadcast the story of his splended work as American prisoner of war in Germany. "Elected by the vote of his 2,400 fellow Americans, who were prisoners at the German prison camp at Rastadt, as Commandant", the Red Cross says, "Sergeant Hallyburton, who for months fought to secure decent treatment for the American captives, is recognized as an authority

Page 58

on their treatment." Although certain rights were finally wrung from the German military jailors, Sergeant Hallyburton says the Germans were guilty of many offences against the prisoners, in particular the regular stealing of American Red Cross food and clothing boxes sent to the Americans.

"The American Red Cross is wonderful," exclaimed Sergeant Hallyburton, suddenly. "It supplied us so well that a prisoner received his regular weekly box never had to touch German stuff." This bulletin of the Red Cross carried a picture of Sergeant Hallyburton. This North Carolina boy is coming out of the war with much honor.

Mr. Fred A. Olds, the versatile writer and amiable curator of the North Carolina Hall of History, writing in The Orphans Friend, under date of Friday, September 9, 1921 says:

A REAL HERO.

"Sergeant Edgar M. Hallyburton stood the acid test and assayed pure gold.

"Taylorsville, the county seat of Alexander, is not a big place, but it is the home of a full size Hero of the World War, and the writer got a great deal of pleasure from a visit to this 100 per cent. American, who is Edgar M. Hallyburton, late sergeant in Co. F, 16th Regiment, U. S. Infantry. He is the worthy wearer of one of the most coveted distinctions in the army, the Distinguished Service Medal, and his letter from General John J. Pershing,

Page 59

he considers as great a distinction as the medal.

"One sees the Distinguished Service Cross quite often, but not one man in a thousand has ever seen a Distinguished Service Medal. In fact, Sergeant Hallyburton was the first enlisted man to receive it. He was also the first American soldier captured by the Germans. It was not alone his bravery in action which won him the medal, but his wonderful head-work, inspirational always, and his American manhood while a prisoner in German camps, which kept his fellow prisoners together, secured for them respect and standing. In other words, this enlisted soldier, by sheer force of his personality, was the chosen head of all the American prisoners in Germany; chosen by them, and not by the Germans.

"He is a quiet man, this Sergeant Hallyburton, but determination and utter fearlessness are written large upon his face. His home village was Stony Point, and from it he joined the regular army in 1907. He was in several branches of the service, went into Mexico with General Pershing in the persuit of Villa the bandit in 1916, and in June, 1917, went to France with the first American contingent, the First Division, all regular troops. The special training for the World War began at once.

"November 3, 1917, his regiment was at the front, in the Luneville sector, in France, and had

Page 60

just marched in. He and about twenty of his Company were in a dug-out 25 feet under ground, that first night at the front. A little before daylight, the Germans laid down a heavy barrage, and rushed this advanced post, and entered the dug-out. They were met by rifle-fire and several were killed and one captured, but they used grenades, killing three Americans; Merle D. Hay, of Des Moines, Iowa; Thomas F. Enright, of Pittsburg, Pa.; and James B. Gresham, of Evansville, Ind., these being the first United States soldiers killed. Five others were wounded, and twelve taken prisoner by the overwhelming force of Germans. The latter were anxious to capture some Americans, hoping to get from them some first-hand information as to the strength of the United States force. The Germans questioned the captured men after they had taken them into their own lines, across 'No Man's Land', and made a photograph of this scene of questioning. These photographs they used as propaganda, and sent them through Switzerland, so newspapers could get them. The three Americans killed were buried with most imposing ceremonies by the French army. The captured men, including Hallyburton, were set down as missing. When the German photograph of the questioning reached the United States there was quite a sensation. No names were given, but the faces were clear. Mr. Geo. B. Hallyburton saw the picture, and his

Page 61

wife and he at once gave notice to the War Department that it was their son who was the central figure in the picture. Bare headed, with one hand in a pocket, he looked fearlessly at the Boches, one of whom is laughing in a sneering way. One may be sure that the questioners, for all their arrogance, got nothing from Hallyburton, who is as firm as flint. The German intelligence officer bombarded him with questions, but the up-standing American neither cringed nor told any secrets. The picture was put to a use of which the Germans never ever dreamed. As soon as Cyrus Dallin, a Massachusetts sculptor, saw it, he made a plaster statuette of Hallyburton, not then even knowing who he was. Then smaller statuettes were made, and those were used in the great Liberty Loan drives. The large statuette was later sent to the parents of Hallyburton. He showed to his captors the true spirit of Americanism and it astonished and puzzled them. He hated them with such a deep and abiding hatred that he would never try to learn or use their language. The next move by the Germans was to put their captives in a sort of cage on a truck, and send them to Germany and hand them from town to town, telling the people these appeared to be all the Americans who had arrived in Europe. The German populace looked at them and treated them as if they were wild beasts on show. Next, the Americans were sent to a prison camp in Tuchel,

Page 62

West Prussia. Six more Americans arrived there a little later, bringing the number up to 18. The Germans hitched them to wagons and forced them to haul firewood 7 miles. Their good clothing had been taken by their cruel captors, and they were given wooden shoes, paper fabric socks, and wretched clothes. The snow was above their knees, they were half-starved, but their spirits were never broken. From town to town where they had been hauled in their cage and exhibited, Hallyburton, chosen as their leader, had written post cards to the American Red Cross, but these cards the Germans withheld, so that it was not until January 12, 1918 that upon demand of the Red Cross in Switzerland their names were given, and the first packages arrived. These supplies saved their lives. Hallyburton says otherwise they could not have endured over two months longer. The Germans made a regular practice to steal from the Red Cross boxes and to appropriate the articles. Once, when 100 pairs of shoes arrived, they stole 96. The American prisoners at Tuchel camp were well organized by Hallyburton, and they stood up for their rights. They were, August 4, 1918, sent to a miserable camp at Rastadt. It was known as a "propaganda" camp, as the Germans tried in every way to undermine the morale of the Americans. There were 550 Americans in this camp when Hallyburton arrived. Pro-German traitors, who had enlisted in

Page 63

the army with this purpose in view, were the spreaders of the vile propaganda, working hand-in-hand with the Germans. Of the Germans, the chief was Capt. von Tauscher, who tried to dynamite a bridge at Detroit, was caught with the dynamite in his suit case and was driven out of America, instead of being properly hanged. He was trying to introduce the two propaganda newspapers the Germans published, "The American In Europe" and the "Continental Times," but he was told point-blank that the Americans would not stand for it. The Americans again chose Hallyburton as their leader, and demanded this and the German general consented. At once the pro-German traitors were ousted. Hallyburton had a hand-picked intelligence staff of 150 men when the armistice began, and the Americans, completely turning the tables on the Germans, did the propaganda work themselves among the younger Boche soldiers, to good purpose, for something happened. The German "revolution" broke out, and it struck Rastadt November 3. The revolutionists opened the prison camp gates and asked the Americans, by that time 2,500 in number, to step out as free men and go into the town. A lot of them did so, but the influenza was raging in town and 83 cases developed among the Americans, three dying of it. At once Hallyburton put on iron-clad discipline, closed the prison camp gates, put on an American provost guard to take

Page 64

the place of the German mutineers, and so kept perfect order until the day in December when the Americans left for home by way of Switzerland. Then he went to Camp Zachary Taylor, Kentucky, and there rejoined his regiment. His outfit at Rastadt actually had cleaner quarters than the German guards, the American barracks being cleaned, or "policed", twice a day. He had a short stay in a horrible German prison at Heuberg, in the Grand Duchey of Baden, this being known as a "Strafe" camp. There he and an "adjunct", a soldier named Geebegan, were closely confined, worked hard, and half-starved.

"Sergeant Hallyburton has placed in the State Hall of History two albums with photographs of his eventful prison life, and a great many newspaper articles and illustrations covering all sorts of phases of it. He also deposits there his Distinguished Service Medal and two letters of intense human interest which he prizes most highly. They are letters any American might well be proud to read and more than proud to have received. One is from Col. W. L. H. Godson, U. S. Military Attache at Berne, Switzerland, and the other from General Pershing."

TRUE BRAVERY.

Hon. F. M. Pinnix, Editor of The Orphan's Friend and Masonic Journal, commenting on the

Page 65

sketch by Mr. Fred A. Olds, pays Sergeant Hallyburton the following tribute:

"Cononel Olds' story of Sergeant Hallyburton in this weeks issue is an inspiring one. North Carolina has the distinction of producing one of the really heroic and useful figures of the war in this fine soldier who not only did his full duty, but did it in a manner and at a time when it counted heavily. Like all really brave men, Sergeant Hallyburton is modest and reserved. Colonel Olds, who knows a man when he sees one, says, "He is a quiet man, this Sergeant Hallyburton, but determination and utter fearlessness are written large on his face." There are various types of bravery; all good, of course, but this type of Sergeant Hallyburton, instantly recognized by his superior officers, is of first rank. Under strain of excitement, of exaltation, of anger, of love, men do prodigies of valor without counting the cost, which means that they do not fully realize the hazards. Weaklings have, for the moment, played the part of heroes. Men, under sudden strong impulses, exhibit stout qualities of heart they cannot summon under normal conditions, and just here is where the real hero is different from the man whose heroism is not stable.

"Hallyburton's is the kind that does not flinch. It is the kind that remained at concert pitch during his full period of service, including all his months as a prisoner of war. It stood the test.

Page 66