Routing the Parkway, 1934

Anne Mitchell Whisnant

Two Parks, Three States, Multiple Routes

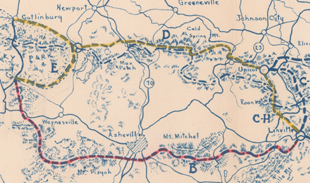

1934 Map Showing Routes favored by both North Carolina and Tennessee

Courtesy Robert C. Browning

Robert C. Browning Papers, MC00279 Box 19, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries.

After 25 years of lobbying by promoters in Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, Congress authorized three new eastern national parks — Great Smoky Mountains in North Carolina and Tennessee, Shenandoah in Virginia, and Mammoth Cave in Kentucky — in 1925 and 1926, extending the national park idea beyond its original home in the American West. Although it would take at least another decade for the states and the federal government to acquire sufficient lands to officially open the parks, citizens and boosters throughout the southern Appalachians grew excited at the prospect of having parks in their backyards. Road development was key to drawing visitors, and after 1931, construction of the ridgetop Skyline Drive (which later lay within the boundaries of Shenandoah National Park) opened up spectacular views — only ninety miles from the nation’s capital, its promoters frequently pointed out — to anyone with a car. The Blue Ridge Parkway emerged in part out of a plan to “extend” Skyline Drive southward to the Great Smokies, connecting the new Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee parks together. [1]

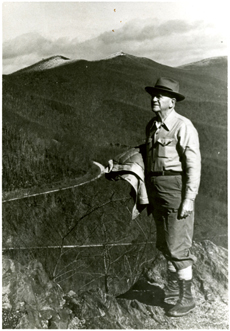

R. Getty Browning, Chief locating engineer for the North Carolina State Highway Commission

Robert C. Browning Papers, MC00279, Special Collections Research Center, North Carolina State University Libraries.

Representatives of the three states containing the Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains parks put together the original proposal for the Parkway, and it was assumed from the beginning that it would touch all three. But the issue of specific routing was left unresolved until after the New Deal’s Public Works Administration approved funding in November 1933. By early 1934, North Carolina and Tennessee had launched into what became an intense year-long battle over the routing. While the route within Virginia was determined quickly, Tennessee and North Carolina developed incompatible proposals for the remaining mileage, and each state lobbied federal officials for months in hopes of winning the "eastern gateway" to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Not until November of 1934 was the issue resolved in favor of the route preferred by North Carolina. [2]

What were the competing routes, where did they come from, what were their merits, and how might the Parkway have been different had federal authorities decided for Tennessee’s plan rather than North Carolina’s?

The North Carolina Route

Planning for the Parkway in North Carolina fell largely to the staff at the State Highway and Public Works Commission, through the office of engineer R. Getty Browning. It was Browning's vision of what the parkway could be — derived in turn from his notion of where the parkway should go — that guided the initial design process. Press reports later called Browning the "architect of the Blue Ridge Parkway" and "the man who is responsible, more than any other man, for the location of the…Parkway in North Carolina rather than in Tennessee." [3] Indeed, a 1950s-era document found in Browning's papers confirmed that "the route which the Parkway follows in North Carolina was mapped for the Secretary of the Interior in 1934 by R. Getty Browning…and it is remarkable that although this map was made before any surveys were begun and was based upon information obtained by Mr. Browning by actually walking over the route, the finished Parkway follows it almost exactly." Although the document is unsigned, records dating from the 1930s support its contention that the North Carolina portion of the Parkway threads the mountains along Browning's route. [4]

The Blue Ridge Parkway project — combining the quest to open areas of beautiful mountain scenery with difficult engineering challenges — captivated Browning from the moment he heard of it in late 1933, and it became his nearly all-consuming work from then until his retirement in 1962.

Postcard, 1918: "Mt. Mitchell Station, Mt. Mitchell, N.C."

North Carolina Postcards, North Carolina Collection, UNC Chapel Hill

As soon as it looked as if the project would be approved for federal funding in late 1933, Browning, along with his colleagues on the Highway Commission and the state Parkway committee, as well as Parkway partisans in western North Carolina’s bustling tourist center of Asheville, set to work preparing North Carolina's routing proposal. The Asheville contingent — made up largely of businessmen and representatives from the Asheville Chamber of Commerce and the Asheville Citizen-Times newspaper — had from the outset been set on a route that would take the Parkway traveler heading to or from the Smokies past several of what they considered their region's finest scenic and tourist attractions: the early tourist village of Blowing Rock; lofty and storied Grandfather Mountain; dramatic Linville Falls; Little Switzerland (the so-called “beauty spot of the Blue Ridge”); Mount Mitchell (highest peak east of the Mississippi); Craggy Gardens; the city of Asheville; and the Native American community at Cherokee.

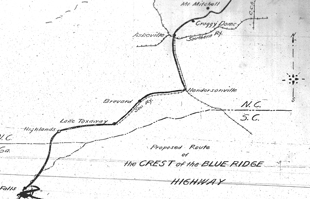

1912 Map of a proposed "Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway"

North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill

The North Carolinians were hardly original in proposing this general path for a scenic road. Parts of the route followed plans for a scenic “Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway” that had been developed more than twenty years earlier by North Carolina’s State Geologist Joseph Hyde Pratt as part of the larger Good Roads movement in North Carolina. According to a description of the 1910-11 route survey published in the Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society, that road would have run from the Boone area to Asheville by way of Blowing Rock, Grandfather Mountain, Linville, Pineola, Mt. Mitchell, and Little Switzerland. Tourism supporters in the mountains hoped that this highway would open the area's scenery to automobile drivers. Although Pratt raised some money and his department completed surveys and even some construction on parts of the route, his idea would have to wait until the 1930s to be fully realized. [5]

By then, the national park building movement boosted interest in many regions in building or marking scenic drives to and through the parks. The development of new eastern national parks fueled a movement for better tourist roads in the southern Appalachians. In the states that were home to the three new eastern parks, this movement first took the form of agitation for what became known as the Eastern National Park-to-Park Highway, intended to join together Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, and Mammoth Cave national parks, as well as some other scenic and historic sites.

The Eastern National Park-to-Park Highway Association, under the leadership of Rep. Maurice H. Thatcher of Kentucky, began lobbying about 1928 for a federally supported highway to join together the three eastern national parks, Washington, D.C., and the new historic sites being developed at Williamsburg, Jamestown, and Yorktown, Virginia. [6]

This project, conceived as an eastern parallel to the West’s decade-old National Park-to-Park Highway, had apparently caught the attention of official Washington by the spring of 1931, when Thatcher convened a meeting of road supporters and congressional delegations from the states involved, as well as enthusiastic officials from the National Park Service (NPS) and the federal Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). Conflict over the highway's route plagued the meeting, but the group finally agreed upon an official map of the extensive project. The Eastern National Park-to-Park Highway was to be a joint federal and state project and was to combine new construction with upgrading of some existing highways. It was to follow established travel routes and would be a major trunk highway on which both recreational and commercial traffic would be permitted. [7]

Despite the grand plans, work on the highway moved agonizingly slowly, and by 1932-33, North Carolina highway supporters were fretting that their state (increasingly strapped for cash as Depression-era governors imposed austerity measures to balance the state’s books) was not doing enough to capitalize on the tourism potential of the developing Great Smoky Mountains National Park. [8]

Approval of the related, but newly conceived Blue Ridge Parkway project for federal funding thus opened a door that had appeared to be closed. By early 1934, the Highway Commission had tentatively investigated and approved the suggested federal Parkway route, and (with considerable input from Browning, who knew the terrain intimately) had elaborated more specifically the route between Asheville and the Park. Much of this part of the road, Browning wrote, would penetrate an "unbroken wilderness" near the Pisgah National Forest. He characterized this section as "the largest unbroken area…in this State which could be considered in connection with the Park [and which] by all means should be protected." It would, he asserted, be "a very great asset to the Parkway." Crossing Mt. Pisgah and the Balsam Mountains (at elevations above 5000 feet nearly all the way), the far southwestern part of the route would end on the reservation lands of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. The state Parkway committee published the completed route proposal in booklet form in early 1934 for presentation to federal officials. [9]

The Tennessee Route

By selecting a route that excluded Tennessee altogether, North Carolinians virtually ensured that an interstate routing battle would erupt. Tennessee proposed a Parkway that dipped into North Carolina before turning west at Linville to cross into Tennessee via Roan Mountain on its way to the Great Smoky Mountains park at Gatlinburg. Such a route better fit federal officials' early idea for the Parkway, but was quite different in character from North Carolina's and generally lay at lower altitudes. [10]

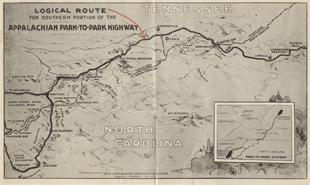

Logical Route for Southern Portion of the Appalachian Park-to-Park Highway

Produced by the Great Smokey Mountains Conservation Association

Courtesy National Park Service

The Tennessee and North Carolina proposals shared the same routing from the North Carolina-Virginia line past Grandfather Mountain to Linville, N.C. At this point, instead of continuing southwesterly, the Tennessee route would have turned nearly due west and crossed into Tennessee, passing the grand Roan Mountain (elevation 6285 feet) — on either a high route on Roan's slopes or a lower route through the adjoining valley — on the way to Unicoi, Tennessee (just south of Johnson City). From there, the Tennessee route would have turned southwest and crept near the North Carolina/Tennessee state line (within what is now the Cherokee National Forest) through the Nolichucky River gorge, across Cold Springs Mountain, through the French Broad River gorge to Delrio and Hartford, and then on to the Smokies, possibly via a fork around the park that would have taken visitors either to Gatlinburg or to Cherokee. [11] The Tennessee route, the Parkway’s first Resident Landscape Architect Stanley Abbott wrote, offered "a variety of mountains, mountain stream valley, and broad river types of scenery," including some high rock cliffs, meadowlands, and woods--all in all a "wide variety of interest." Its disadvantage, he observed, was its "relatively low elevation." [12]

First Hearings and Arguments: Baltimore, February 1934

With a flood of incoming letters and intense lobbying of federal officials by partisans from both Tennessee and North Carolina in late 1933 and early 1934, it soon became clear to the federal committee appointed to determine the Parkway route (Regional Public Works Administrator George Radcliffe, chair; NPS Director Arno B. Cammerer; and federal Bureau of Public Roads Chief Thomas H. MacDonald) that hearings were needed to allow the committee to sort out the merits of each proposal. The committee summoned representatives from each state to Baltimore to make their arguments at a three-day forum in Baltimore in early February. [13]

Joining chair Radcliffe at the hearing tables were several experts from both NPS and BPR. Theodore Straus, a Baltimore engineer (sometimes associated with the origination of the Shenandoah-Great Smoky Mountains parkway idea) serving on the regional PWA advisory board, acted as Radcliffe's second in command. With him sat a team of engineers and landscape architects, most prominent of whom was consulting landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke, a pioneer in the nation's parkway-building efforts who had supervised construction of the nation's first parkway (the Bronx River Parkway), and had subsequently served as landscape architect for the Westchester County Parkway Commission during its building campaign of the 1920s. Working with Clarke were NPS Chief Landscape Architect Thomas C. Vint, BPR engineer H. J. Spelman, and newly hired Resident Landscape Architect Abbott. [14]

Abbott would become the Parkway's first Superintendent and one of its principal early designers, but when he was hired in December of 1933 to work on the project, he was an unknown and relatively inexperienced twenty-six-year-old only three years out of Cornell's landscape architecture program. But he had worked with the eminent Gilmore Clarke on the Westchester County Parks Commission, and this connection led to his Blue Ridge Parkway position. For ten years, Abbott would head the Parkway project, designing the landscape for what would become the longest parkway yet built in the United States. [15]

To the hearing to present North Carolina’s case came a twenty-six-person delegation that included Governor J.C.B. Ehringhaus, most of the state's congressional delegation, most of the members of the state-appointed Parkway committee, R. Getty Browning and State Highway Commission Chair E. B. Jeffress, other members of the State Highway Commission, and developer George Stephens of Asheville. For over three hours, the North Carolinians presented their case for leaving Tennessee out of the Parkway picture and building all the non-Virginia mileage in their state. [16]

As the person with the most first-hand knowledge of their route, senior locating engineer Browning played the key role in the presentation. Armed with several maps that covered nearly an entire side of the hearing room, Browning patiently, professionally, but quickly took his listeners over highlights of the projected route, relating it to existing towns, roads, and rivers. North Carolina’s delegates also stressed the expected economic effects of the routing decision, reminding committee members of the state’s long commitment to tourism, which Highway Commission Chair Jeffress asserted was the mountain region’s "natural business." [17]

North Carolinians observing the Tennessee presentation doubtless felt smug as Tennessee Senator Kenneth McKellar pressed his state's case with accusations of bias and favoritism within the federal committee and threats to use his influence in Congress to withhold funding for the road were it not located to his liking. Halfway through Tennessee's allotted time, General Frank Maloney of the State Highway Department, also armed with detailed maps, rose to pick up the pieces after McKellar's disastrous speech. Maloney detailed the possible advantages of Tennessee's less-elevated route: relief from mountain driving, the beauty of the streamside sections, and the improved camping opportunities that a mix of high and low elevations might offer. He tried to show that "the highway I have mentioned…would be of a scenic beauty that is unsurpassed" and that it would "[divide] the distance equally between the two states… [giving] no one the advantage in any way." Other Tennessee speakers concurred, but, compared with the facts, fervor, and polish of North Carolina's presentation, the Tennesseans' case seemed vague, disorganized, whiny, and weak. Besides asking for equity in the treatment of the two states, they seemed unable to offer many compelling reasons why the Parkway ought to follow their route. [18]

After the hearing, at Browning's urging, Representative Robert Doughton arranged for himself, developer Stephens, and Governor Ehringhaus to have a post-hearing audience with President Roosevelt, where they presented him with an expensively produced red leather album full of "beautiful pictures in natural colors" of the scenic spots they hoped the Parkway would include. [19]

Competing Visions for the Parkway: Getty Browning and Stanley Abbott

As Getty Browning labored through the spring and summer of 1934 to secure adoption of his ridgetop western North Carolina parkway plan, he confronted head-on the recommendations of NPS Resident Landscape Architect Abbott. In simultaneous June 1934 reports, the two men elaborated their quite different visions for the parkway.

Five days before the federal Radcliffe committee issued its recommendations, Abbott submitted to the National Park Service's Chief Landscape Architect Thomas Vint (and through him to Director Cammerer) conclusions from his five- month investigation of the competing routes. His report, undoubtedly the basis of the Radcliffe Committee's recommendations, favored the Tennessee route, with its varied valley and mountain scenery and elevations. In advocating this route, Abbott envisioned the Parkway primarily as a "Park to Park connection" that should thus be "as directional as possible consistent with its location in interesting territory." A Parkway traveler, that is, should "feel that by and large he is traveling on the shortest line between the two Parks." Abbott also thought the North Carolina route would be too expensive and damaging to construct. [20]

Abbott assumed that most Parkway travelers would be driving all the way from one park to the other. Motorists, he felt, might "become tired with 500 miles of mountain scenery" offered by Browning's mountaintop North Carolina route. He concluded that "the mountain parkway would not be used by a sufficient number of tourists nor have great enough recreation value to justify its construction." "It is believed," he continued, "that a mountain or skyline road is distinctly a type to be developed within a park such as Shenandoah National Park and that the idea is not adaptable in this region to a 500 mile Park to Park connection." He suggested that the Parkway might even be built (albeit with scenic features designed in) to accommodate regional passenger traffic, thus combining the paradigms of regular highway and scenic parkway to create a commuter parkway similar to those constructed elsewhere in the country. Abbott's rather conservative view thus adhered closely to previous models of scenic but largely urban, utilitarian parkways. [21]

Browning's vision for the Parkway was both more in keeping with dramatically scenic roads in western parks and closer to what the Parkway ultimately became than was Abbott's. At about the same moment as Abbott was submitting his report, Browning mailed to the Radcliffe Committee a lengthy argument for his North Carolina route. In this document as well as in the two routing hearings held by federal officials, Browning articulated his vision for an all-mountaintop, truly scenic Parkway whose main aim was not merely to transport tourists from one place to another, but also to present breathtaking scenery along the way.

The fifty-one year-old Browning, an avid outdoorsman and locating engineer with many years of experience investigating and plotting alternative highway locations, called the Parkway "one of the most worthwhile engineering feats of modern times." He described the spectacular sights to be seen at each juncture and the feasibility of construction along the route he proposed. Stunningly high peaks, distant views, dense woodlands, and stands of flora such as rhododendron and laurel interested him most, and he argued that a ridgetop parkway would make it possible for thousands of non-hikers to enjoy what he and other outdoor enthusiasts had seen. He argued passionately that "no where else in the United States, so far as I know, could such an excellent location for a parkway be found, if splendid scenery, high elevation, profusion of beautiful shrubbery, favorable climatic conditions, reasonable construction cost and accessibility from all sections of the country are to be considered." In contrast to Abbott, moreover, Browning thought that summer visitors seeking the coolness of high altitudes would be disappointed "to find [the Parkway] following the narrow, hot valleys at low elevations, when they might just as well have had the advantage of the cool, beautiful mountain route." "Shall the Parkway be just another highway," he asked the Committee, "or shall it be a really outstanding, beautiful driveway through the most delightful and attractive country that the whole region affords?" [22]

Near Miss: Federal Committee Recommends Tennessee Route

As the 1934 Rhododendron Festival opened in Asheville, the federal Radcliffe Committee delivered the much-feared fatal blow: they recommended the Tennessee-sponsored route. [23] The report was not made public until months later, but someone leaked the news to Asheville-based Parkway supporters gathered on June 15 to greet a contingent of dignitaries from Washington (including National Park Service Director Arno B. Cammerer and Mrs. Anna Ickes, wife of Interior Secretary Harold Ickes).

From that fateful night until early fall, North Carolina route supporters conducted a full-court press on both Secretary Ickes and President Roosevelt to convince them not to adopt the committee’s recommendations. Ickes, for his part, fixed the part of the route from the Shenandoah National Park to Blowing Rock, North Carolina (agreed upon by all parties), and announced in late July that a decision on the controversial sections would await the outcome of further hearings in September.

Second Hearings: Washington, September 1934

North Carolina partisans spared no expense in preparing for the fall hearing. Newspapers throughout North Carolina reprinted pro-Parkway editorials supplied by the Citizen-Times, and the Asheville Chamber of Commerce drummed up support among civic clubs and citizens throughout the western part of the state. The Chamber chartered a train to ferry 240 "prominent citizens" (mostly business, civic, and political leaders) to the hearing, and reserved ten rooms and a parlor in the Mayflower Hotel for their use. On hearing day, nearly four hundred cheering North Carolina supporters crowded the Interior Department auditorium. Tennessee, likewise, sent a trainload of partisans, making for a much more boisterous and public second hearing than the one in Baltimore had been seven months earlier. Despite Ickes's pleas that the standing-room-only crowd hold its applause, the rowdy groups cheered and clapped as their representatives rose to speak. [24]

North Carolina's top political leaders — Governor Ehringhaus and the state's senators and congressmen — headed up the delegation. But leaders from the Asheville Chamber prepared the state's hour-and-a-half presentation. And when the plan was announced, only ten minutes were allotted to Governor Ehringhaus and only five apiece to the state's Congressional leaders. North Carolina's hopes, and a full hour of the state's presentation, were entrusted to R. Getty Browning. With newly drawn relief maps, charts, and a long pointer, Browning again put forward his vision for an all-mountaintop Parkway in place of the mountain-and-valley plan proposed by Tennessee (and favored by Abbott). Most presciently, unlike others who thought of the Parkway merely as an attractive means of connecting the two national parks, Browning argued that it was likely to become an attraction in itself. "This parkway is so long," he speculated, "that a great many people will probably not drive from one end to the other, so we thought that every mile of it ought to be located as carefully as possible."

Tennessee’s delegation arrived far better prepared than they had been in Baltimore, with more concrete proposals, clearer justifications for their varied-topography route, and calmer rhetoric backed now by the investigations and recommendations of the Radcliffe committee. That committee's report had never been made public, and in fact the North Carolina partisans — unlike the Tennesseans — had yet to see it. To the North Carolinians' dismay, however, Tennessee's speakers had obtained a copy, and they used it to their advantage, arguing that the committee's investigations had been thorough and careful and that their suggestions ought to be followed. Bolstered by the report, Tennessee's representatives portrayed their position as fair and reasonable, emphasizing their state's willingness to share the parkway while characterizing their sister state's efforts to monopolize the project as "selfish and greedy." One of Tennessee's congressmen pointedly accused the North Carolinians of being concerned not with the national or even the broadly regional interests at stake in the project, but only with the welfare of the city of Asheville. [25] In a brief submitted along with their presentation, the Tennesseans bolstered their position further with a conciliatory proposal for a fork at the western end of the parkway to give entrances to the Great Smoky Mountains Park in both states. [26]

In spite of their outward confidence going into the hearing and the real strengths of their case — especially from engineering and scenery standpoints — the North Carolina delegation (with the exception of Browning) left the Interior Building shaken by Tennessee's presentations, particularly by their use of the Radcliffe Committee report. In the wake of the hearing, the North Carolina delegation backtracked, notifying Park Service Director Cammerer and others in Washington that North Carolina would be satisfied with a looped or forked Parkway that would serve both east Tennessee and western North Carolina on its western end (and that would include Asheville and most of North Carolina's desired route). Such an arrangement would, it was expected, be acceptable to the Tennesseans as well as to the Radcliffe committee, which had mentioned that option in their report. In the days after the hearing, the North Carolina delegation also discussed other compromise routes in private meetings with Ickes, Cammerer and others at the Park Service and Interior Department. [27]

While the Asheville-based partisans shifted to the more defensive stance of advocating a loop, fork, or other compromise route, Browning pushed confidently for the original plan. As it turned out, Browning's vision for the Parkway prevailed in a follow-up brief submitted to Ickes under Governor Ehringhaus's signature a week after the hearing. "This project," the brief maintained, "belongs neither to Virginia, Tennessee, nor North Carolina. It is a national project and…must be in keeping with national, not local, desires and needs…We cannot believe that the gentlemen who composed [the Radcliffe Committee], having once started along the crest of the great watershed and attained the high altitudes and the magnificent scenery that it presents, and the easy grade and alignment afforded by its gradually undulating surface, would have abruptly departed from this natural highway and laid out a route across the barriers of streams and gorges to seek the scenery of a few outstanding mountains, when scores of higher peaks lay along the course upon which they had started, unless they felt constrained by some sense of duty to place a part of the route on one side and a part on the other side of the State boundary line." While the brief did go on to mention the Asheville economic situation and the possibility of a forked parkway, those concerns were buried at the end by Browning's confidence that his vision of a mountaintop parkway would prevail. [28]

Decision for North Carolina

Finally, on November 10, 1934, the long-awaited word arrived: overruling the Radcliffe Committee, Ickes adopted North Carolina's route. Unexpectedly, there was no compromise, no sharing, no fork, and no loop, just a complete victory for the North Carolina cause. Tennessee would get no parkway; North Carolina would get nearly 250 miles, with the remaining 220 going to Virginia. [29]

Ickes' Decision Placing Route For Parkway In N. C. Hailed As Great Victory By Entire State

Asheville Citizen, November 13, 1934

North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill

Consolation Prize: Tennessee’s Foothills Parkway

In the wake of the decision, Tennessee’s partisans did not put up a fight, but some of them held on to their vision for a parkway on the northwest side of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In 1944, they secured Congressional approval for a consolation prize of sorts, the 72-mile “Foothills Parkway” designed by General Maloney and planned to stretch from what became the Interstate 40 corridor near Cosby, Tennessee, at the northeastern end to Chilhowee Lake on the southwestern end. The project received its first funding as part of the Park Service’s post-1956 MISSION 66 program, and construction began in 1960. By 2009, 22.5 miles of the parkway had been completed and opened to traffic; new funding under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act authorized nearly $25 million in early 2010 for work on an 800-foot soaring bridge along the so-called “missing link” of partially completed sections of the middle of the parkway. [30]

Interactive Maps

Click the links below to view several of our georeferenced maps that help us understand what was at stake in the 1934 routing conflict and how things might have been different had another routing decision been made. If you download all of them to Google Earth (see link below each map), you can layer them all on top of each other, turn them on and off, and change the transparency of each so as to see the relationships between the early Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway, the Eastern National Park-to-Park Highway proposal, the various routes proposed for the Blue Ridge Parkway, the final location of the Parkway, and the Foothills Parkway later developed in Tennessee.

- American Automobile Association NC Map, 1920

- This map shows the Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway.

- State Highway System of North Carolina, 1931

- This map, published shortly before the Parkway idea emerged, depicts the pre-Parkway road network in western North Carolina, including showing the Crest of the Blue Ridge Highway.

- Eastern National Park-to-Park Highway, 1931

- This map shows the proposed highway system linking several new eastern National Park areas.

- Proposed Shenandoah-Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway, 1934

- This map shows all of the routing alternatives for the future Blue Ridge Parkway, including the full Tennessee proposal and the North Carolina proposal.

- Logical Route for the Southern Portion of the Appalachian Park-to-Park Highway, 1934

- This map shows the proposed, but ultimately not adopted, Tennessee route.

- Proposed Scenic Parkway through North Carolina, 1934

- This map clearly shows the North Carolina proposal.

- Perspective View of Proposed Park to Park Highway Through North Carolina, 1934

- This map, one of a set of dramatic graphics developed and used by North Carolina officials during the 1934 routing conflict, gives an artistic rendering of North Carolina's proposal.

- Foothills Parkway Map, 2009

- This 2009 map shows the recent status of the Foothills Parkway near the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

2. On the three states' involvement in the original formulation of the project, see Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), chapter 1; and the initial proposal to Secretary Ickes: George L. Radcliffe, Thomas H. MacDonald, E. B. Jeffress, O. F. Goetz, H. G. Shirley, R. Y. Stuart, and Arno B. Cammerer to Harold L. Ickes, 17 October 1933, Ickes Papers, Box 248, Library of Congress. For other early evidence of North Carolinians' commitment to this route, see also Fred L. Weede to Josiah W. Bailey, 12 October 1933, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Box 311, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library (hereafter cited as Bailey Papers). Weede himself began stirring up support for this route among western North Carolina civic organizations as early as October of 1933. He describes some of these efforts in Fred L. Weed to Robert L. Doughton, 24 October 1933, Robert Lee Doughton Papers, Box 7, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (hereafter cited as RLDP); Fred L. Weede to Arno B. Cammerer, 7 December 1933, Record Group 79 (National Park Service), Central Classified Files, 1933–49, Entry 7B, “National Parkways–Blue Ridge,” Boxes 2711–75 Box 2713, College Park, Maryland, National Archives II (hereafter cited as RG 79 CCF7B).; and Fred L. Weede, to R. L. Doughton, 13 December 1933, RLDP, Box 7, SHC.

3. North Carolina State Highway and Public Works Commission, "Press Release upon Retirement of R. Getty Browning," 27 July 1956, RG 5, Box 59, BRPA; "Engineer Browning Dies At 82," Asheville Citizen, 31 January 1966, A1

4. R. Getty Browning, Blue Ridge Parkway, 7 October1953, PCRCB.

5. Harry Wilson McKown, Jr. “Roads and Reform: The Good Roads Movement in North Carolina, 1885–1921.” (Master’s thesis, University of North Carolina, 1972) 30-39 and 34-39; Brown, Cecil Kenneth. "The State Highway System of North Carolina: Its Evolution and Present Status." (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1931), 33-36 and 57-59; Preston, Howard Lawrence. "Dirt Roads to Dixie: Accessibility and Modernization in the South, 1885–1935." (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991) 21-25 and 37-38. This highway, had it been built, would have connected towns along the Blue Ridge from Virginia to Georgia, several of which (Blowing Rock, Little Switzerland, and Asheville) later lay on the Blue Ridge Parkway route.

6. It is not clear exactly when the Shenandoah-Great Smokies-Mammoth Cave effort got under way. At least one source in 1931 states that Lenoir, N.C., businessman R. L. Gwyn had by that time been lobbying for such a park-to-park highway for two years. Gwyn himself reported in 1933 that he had been at work on the project for five years. What is most important, however, is that by 1931 an organized constituency was working in favor of this road--distributing maps and holding serious meetings with officials in Washington.

7.R. L. Gwyn to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 20 February 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; R. L. Gwyn to E. B. Jeffress, 5 August 1932, Bailey Papers, Box 310.; R. L. Gwyn to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 20 February 1933, J. C. B. Ehringhaus Papers, Box 152, North Carolina State Archives (hereafter cited as JCBEP); Maurice H. Thatcher to E. B. Jeffress,19 July 1933, RLDP, Box 10. Thatcher's letter emphasized that the North Carolina State Highway Commission was supposed to be building that state's sections of the Park-to-Park Highway. Thatcher also touched upon the fact, however, that the highway was "recognized" by the National Park Service as the main route between the three eastern parks; Maurice H. Thatcher to Harold L. Ickes, 21 October 1933, RG 79 CCF 7B , Box 2713, NARA II. Thatcher noted in this letter, written as the proposals for the similar but distinct Blue Ridge Parkway were coming to public attention, that as of the fall of 1933, most of the mileage to be included in the ENPPH was already hard surfaced, "though much of it needs reconstruction and a better engineering treatment." For a popular article on the Eastern National Park to Park Highway, see Borah, Leo A. “A Patriotic Pilgrimage to Eastern National Parks: History and Beauty Live along Paved Roads, Once Indian Trails, through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia.” National Geographic 65, no. 6 (1934): 663–97.

8. See Major John A. Bechtel, "[Most of main title obscured] . . . To Smoky Park: Tennessee Rapidly Going Forward With Plans for Western Entrance But N.C. Has No Major Proposals, Scenic Beauty, Short Mileage Routes Sought," Carolina Motor News, June 1932, A1; R. L. Gwyn to R. L. Doughton, 4 August 1932, Box 310, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University. R. L. Gwyn to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 20 February 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; R. L. Gwyn to E. B. Jeffress, 5 August 1932, Box 310, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.; R. L. Gwyn to R. L. Doughton, 4 August 1932, Box 310, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.; R. L. Gwyn to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 20 February 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; R. L. Gwyn to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 20 February 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; Badger, Anthony J. North Carolina and the New Deal. Raleigh (North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Division of Archives and History 1981), 8-12; Abrams, Douglas Carl. Conservative Constraints: North Carolina and the New Deal. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997) 17, 190-213; J. C. B. Ehringhaus to R. L. Gwyn, 27 February 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA.

9. RGB to George L. Radcliffe, 1 June 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2711, NARA II; North Carolina Committee, "Description of a Route through North Carolina," 1934, RG 79, National Archives II; Weede, "Battle for the Blue Ridge Parkway," PML; RGB to Theodore Straus, 17 January 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, box 2711, NARA II.

10. Weede, "Battle for the Blue Ridge Parkway," 8, PML; Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, NARA II. On the route proposed by Tennessee, see Public Works Administration, "The Shenandoah Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project: Proceedings of the meetings held in Baltimore, February 5, 6, 7, 1934," 7 February, 1934, 23-27, Record Group 79 (National Park Service), Central Classified Files, 1933–49, Entry 18, “Records of Arno B. Cammerer, 1920–1940,” Box 2, College Park, Maryland, National Archives II. This route would have divided the non-Virginia mileage approximately equally between Tennessee and North Carolina.

11. Map of Tennessee route ("Maloney Route" named for the Knoxville engineer who laid it out), in Jolley, Harley E. The Blue Ridge Parkway. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969) 62-63.

12. Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, NARA II;

13. George Stephens to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 21 December 1933, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; and Fred L. Weede to R. L. Doughton, 13 December 1933, RLDP, Box 7. On the deluge of routing requests pouring into federal offices, see letters in RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2711, NARA II. See also Thomas C. Vint to W. T. Kennerly, 29 January 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2713, NARA II.

14. Snow, W. Brewster, ed. The Highway and the Landscape (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1959), v-vi.

15. Birnbaum and Crowder, Pioneers of American Landscape Design, 6. Abbott did not initially favor the location of the Parkway along the North Carolina-sponsored route. See Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, NARA II; Public Works Administration, "The Shenandoah Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project," 5 February 1934, 5-37, RG 79, NARA II.

16. Public Works Administration, "The Shenandoah Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project," 6 February 1934, 1-3, 5-6, 54, RG 79, NARA II;

17. Public Works Administration, "The Shenandoah Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project," 6 February 1934, 27, 34, 36, 43, RG 79, NARA II; North Carolina Committee on Federal Parkway, "Description of a Route through North Carolina," 1934, RG 79, NARA II.

18. Public Works Administration, "The Shenandoah Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project," 7 February 1934, 5-19, RG 79, NARA II, 11, 23-38; Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, NARA II;

19. George Stephens to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 2 February 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; George Stephens to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 24 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; Fred L. Weede to Josiah W. Bailey, 10 February 1934, Bailey Papers, Box 311, DU; C. A. Unchurch, Jr.,; and Weede, "Battle for the Blue Ridge Parkway," PML.

20. Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, NARA II; Thomas C. Vint to Director, NPS, 8 June 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2711, NARA II.

21. Resident Landscape Architect, "Report: Proposed Locations, Shenandoah Great Smoky Mountains National Parkway," 8 June 1934, RG 79, NARA II.

22. RGB to George L. Radcliffe, 1 June 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2711, NARA II.

23. George L. Radcliffe, Thomas H. MacDonald, and Arno B. Cammerer to Harold L. Ickes, 13 June 1934, POF 6p, Box 14, FDRL.

24. RGB to Josephus Daniels, 8 September 1934, Daniels Papers, Box 676, Great Smoky Mountains File, LC; Fred L. Weede to Josiah A. Bailey, 8 September 1934, PML (In Weede, "Battle for the Blue Ridge Parkway," PML); Charles A. Webb to Josiah W. Bailey, 10 September 1934, Box 312, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.; George Stephens to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 11 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; Advertisement, "On To Washington!" Asheville Citizen, 16 September 1934, C10; Charles A. Webb to Josephus Daniels, 21 September 1934, Daniels Papers, Box 676, Great Smoky Mountains File, LC.

25. Federal Emergency Administration on Public Works, "Hearing in Re: Route of Proposed Scenic Parkway," RG 79, NARA II; "Tennesseans Reveal Ickes's Committee Reported That Two-State Route Was Best," Knoxville News-Sentinel, 19 September 1934, 10.

26. David C. Chapman to Harold L. Ickes, 18 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; "Tennessee Loses Park-to-Park Road," Knoxville News-Sentinel, 12 November 1934, 1, 14.

27. Charles A. Webb to Arno B. Cammerer, 20 September 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2714, NARA II. Governor Ehringhaus apparently also favored a loop or fork proposal. See Albert L. Cox to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 19 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA; and J. C. B. Ehringhaus to Albert L. Cox, 21 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA. A flurry of correspondence in the aftermath of the hearing and the possibility of a forked Parkway indicates that most of the principal Asheville-based supporters, with the especial encouragement of Senator Bailey, were now pushing the fork solution: see George Stephens to Josephus Daniels, 20 September 1934 and Charles A. Webb to Josephus Daniels, 21 September 1934, both in Daniels Papers, Box 676, Great Smoky Mountains File, LC; Robert Lathan to Josiah W. Bailey, 21 September 1934, Bailey Papers, Box 312.; Josiah W. Bailey to Robert Lathan, Asheville, NC, 24 September 1934, Bailey Papers, Box 312.; Josiah W. Bailey to Harry Slattery, 27 September 1934, Box Bailey Papers, Box 312.; Robert Lathan to Senator Josiah W. Bailey, 10 October 1934, Bailey Papers, Box 312.; See also Fred L. Weede to Gilliland Stikeleather,17 October 1934, POF 6p, Box 14, FDRL. Browning seems to have been almost the only North Carolinian who did not panic in the wake of the hearing. He felt that the state's presentation had been effective, and he was confident that Ickes was favorable to North Carolina's route. "I am not discouraged in the slightest," he told Daniels. "I believe that we are going to win." Browning's confidence may have arisen from having been in particularly close touch with Ickes and Daniels in the wake of Daniels' June visit to Washington, perhaps giving him a firmer sense of the commitments that had been made by Ickes and Roosevelt. See RGB to Josephus Daniels, 22 September 1934, Daniels Papers, Box 676, Great Smoky Mountains File, LC. For the Radcliffe Committee's discussion of a possible fork, see George L. Radcliffe, Thomas H. MacDonald, and Arno B. Cammerer to Harold L. Ickes, 13 June 1934, POF 6p, Box 14, FDRL. The report suggested that the new Parkway be thought of as "a unit in a National Parkway to serve the entire chain of Atlantic States," and that as such, their recommended route would allow for a forking at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, with "one fork continuing on in Tennessee connecting with [the] Natchez Trail toward New Orleans, and the other branching toward Atlanta and Florida. The fork might also be placed in the vicinity of Grandfather Mountain, utilizing much of the route proposed in North Carolina to the south of Asheville." The North Carolinians felt after the hearing that if they had known of this portion of the Radcliffe Committee's recommendations, they could have argued for the forked parkway instead of asking for exclusive construction of their own route. See also Robert Lathan to Harold L. Ickes, 21 September 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2714, NARA II.

28. Senator Bailey reported that Browning was the author of the brief, but both he and George Stephens offered suggestions. See Josiah W. Bailey to RGB, 21 September 1934 and Josiah W. Bailey to Robert Lathan, 24 September 1934, both found in Bailey Papers, Box 312, The Josiah William Bailey Papers, Duke University Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library.; George Stephens to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 24 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA. The brief was submitted under Ehringhaus's signature, although as a somewhat peripheral figure in the Parkway battle, he almost certainly did not write it. See J. C. B. Ehringhaus to Harold L. Ickes, 25 September 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA.

29. Ickes's official announcement was carried in a letter to Governor Ehringhaus: Harold L. Ickes to J. C. B. Ehringhaus, 10 November 1934, JCBEP, Box 152, NCSA. A copy was released to the press on November 12, 1934. Also see DOI, "Memorandum for the Press," 12 November 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2713, NARA II. Tennessee's parkway supporters were, of course, incensed and complained loudly both to Ickes and to FDR.

30. C. Brenden Martin, “Foothills Parkway,” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=477; and Great Smoky Mountains National Park, “Briefing Statement: Completion of the Foothills Parkway,” May 2009, http://www.nps.gov/grsm/parkmgmt/upload/Foothills%20Parkway%205-14%20-%2009.doc; Kurt Repanshek, “Contract Issued For "Missing Link" on Foothills Parkway in Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” National Parks Traveler, 16 January 2010.