Some Efforts of American Negroes for Their Own Social Betterment.

Report of an Investigation under the Direction of Atlanta University;

Together with the Proceedings of the Third Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems,

Held at Atlanta University, May 25-26, 1898:

Electronic Edition.

DuBois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963, Ed.

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Apex Data Servies, Inc.

Images scanned by Jill Kuhn

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc. and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 275K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Some Efforts of American Negroes for Their Own Social Betterment. Report of an Investigation under the Direction of Atlanta University; Together with the Proceedings of the Third Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, Held at Atlanta University, May 25-26, 1898.

Edited by W. E. Burghardt Du Bois, Ph. D.

66 p.

Atlanta

Atlanta University Press

1898

Atlanta University Publications No. 3

Call number E185.5 .A88 no. 1-5 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

Footnotes appearing with paragraphs are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs. Footnotes appearing within tables are inserted at the bottom of the table in which the reference occurs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- Social conditions.

- African Americans -- Societies, etc.

- African Americans -- Charities.

- African Americans -- History.

- Cooperative societies -- United States.

Revision History:

- 2001-07-18,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-08-16,

Jill Kuhn, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-07-26,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcription and TEI/SGML encoding

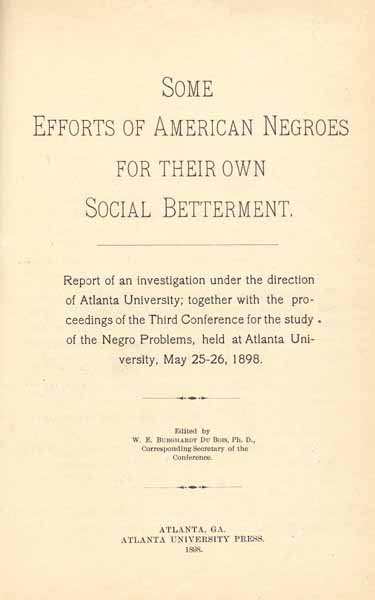

SOME

EFFORTS OF AMERICAN NEGROES

FOR THEIR OWN

SOCIAL BETTERMENT.

Report of an investigation under the direction

of Atlanta University; together with the proceedings

of the Third Conference for the study.

of the Negro Problems, held at Atlanta University,

May 25-26, 1898.

Edited by

W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS, Ph. D.,

Corresponding Secretary of the

Conference.

ATLANTA, GA.

ATLANTA UNIVERSITY PRESS.

1898.

The Corresponding Secretary of the Atlanta Conference will upon request undertake to furnish correspondents with information upon the Negro problems, so far as possible; or will point out such sources as exist, where data may be obtained. No charge will be made except for actual expenses incurred.

CONTENTS.

- INTRODUCTION . . . . . 3

- I. RESULTS OF THE INVESTIGATION THE EDITOR.

- 1. THE SCOPE OF THE INQUIRY . . . . . 4

- 2. GENERAL CHARACTER OF THE ORGANIZATIONS . . . . . 4

- 3. THE CHURCH . . . . . 5

- 4. THE SECRET SOCIETY . . . . . 12

- 5. BENEFICIAL AND INSURANCE SOCIETIES . . . . . 18

- 6. COOPERATIVE BUSINESS . . . . . 21

- 7. BENEVOLENCE . . . . . 27

- 8. GENERAL SUMMARY . . . . . 42

- II. PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE . . . . . 45

- RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE CONFERENCE . . . . . 47

- III. PAPERS SUBMITTED TO THE CONFERENCE . . . . . 49

- THE CHURCH AS AN INSTITUTION FOR SOCIAL BETTERMENT; Rev. H. H. Proctor . . . . . 50

- SECRET AND BENEFICIAL SOCIETIES OF ATLANTA, GA.; Dr. H. R. Butler . . . . . 52

- ORGANIZED EFFORTS OF NEGROES FOR THEIR OWN SOCIAL BETTERMENT IN PETERSBURG, VA.; Prof. J. M. Colson . . . . . 54

- THE WORK OF THE WOMAN'S LEAGUE, WASHINGTON, D. C.; Mrs. Helen A. Cook . . . . . 57

- THE CARRIE STEELE ORPHANAGE; Miss Minnie L. Perry . . . . . 60

- MORTALITY OF NEGROES L. M. Hershaw . . . . . 62

Page 2

"The sky of brightest grey seems dark

To one whose sky was ever white,

To one who never knew a spark

Thro' all his life of love or light,

The greyest cloud seems overbright."

--Dunbar.

Page 3

INTRODUCTION.

Atlanta University is an institution for the higher education of Negro youth. It seeks by maintaining a high standard of scholarship and deportment, to sift out and train thoroughly, talented members of this race to be leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among the masses.

Furthermore, Atlanta University recognizes that it is its duty as a seat of learning to throw as much light as possible upon the intricate social problems affecting these masses, for the enlightenment of its graduates and of the general public. It has therefore for the last three years sought to unite its own graduates, the graduates of similar institutions, and educated Negroes in general, throughout the South, in an effort to study carefully and thoroughly certain definite aspects of the Negro problems.

Graduates of Fisk University, Berea College, Lincoln University, Spelman Seminary, Howard University, the Meharry Medical College, and other institutions have kindly joined in this movement and added their efforts to those of the graduates of Atlanta, and have in the last three years helped to conduct three investigations: One in 1896 into the Mortality of Negroes in Cities; another in 1897 into the General Social and Physical Condition of 5,000 Negroes living in selected parts of certain Southern cities; finally, in 1898, inquiry has been made to ascertain what efforts Negroes are themselves making to better their social condition by means of organization.

The results of this last investigation are presented in this pamphlet. Next year some phases of the economic situation of the Negro will be studied. It is hoped that these studies will have the active aid and co-operation of all those who are interested in this method of making easier the solution of the Negro problems.

Page 4

RESULTS OF THE INVESTIGATION.

BY THE EDITOR.

1. The Scope of the Inquiry.

--The aim of this study is to make a tentative inquiry into the organized life of American Negroes. It is often asked What is the Negro doing to help himself after a quarter century of outside aid? The main answers to this question hitherto have naturally recorded individual efforts in education, the accumulation of property and the establishment of homes. The real test, however, of the advance of any group of people in civilization is the extent to which they are able to organize and systematise their efforts for the common weal; and the highest expression of organized life is the organization for purely benevolent and reformatory purposes. An inquiry then into the organizations of American Negroes which have the social betterment of the mass of the race for their object, would be an instructive measure of their advance in civilization. To be of the highest value such an investigation should be exhaustive, covering the whole country, and recording all species of effort. Funds were not available for such an inquiry. The method followed therefore was to choose nine Southern cities of varying size and to have selected in them such organizations of Negroes as were engaged in benevolent and reformatory work. The cities from which returns were obtained were: Washington, D. C., Petersburg, Va., Augusta, Ga., Atlanta, Ga., Mobile, Ala., Bowling Green, Ky., Clarkesville, Tenn., Fort Smith, Ark., and Galveston, Tex. Graduates of Atlanta University, Fisk University, Howard University, the Meharry Medical College, and other Negro institutions co-operated in gathering the information desired.

No attempt was made to catalogue all charitable and reformatory efforts but rather to illustrate the character of the work being done by typical examples. In one case, Petersburg, Va., nearly all efforts of all kinds were reported in order to illustrate the full activity of one group. The report for one large city, Washington, was pretty full, although not exhaustive. In all of the other localities only selected organizations were reported. The returns being for the most part direct and reduced to a basis of actual figures seem to be reliable.

2. General Character of the Organizations.

--It is natural that to-day the bulk of organized efforts of Negroes in any direction should centre in the Church. The Negro Church is the only social institution of the Negroes which started in the African forest and survived slavery; under the leadership of the priest and medicine man, afterward of the Christian pastor, the Church preserved in itself the remnants of African tribal life and became after emancipation the centre of Negro social life. So that to-day the Negro population of the United States is virtually divided into Church congregations, which are the real units of the race life. It is natural therefore that charitable and rescue work among Negroes should first

Page 5

be found in the churches and reach there its greatest development. Of the 236 efforts and institutions reported in this inquiry, seventy-nine are churches.

Next in importance to churches come the Negro secret societies. When the mystery and rites of African fetishism faded into the simpler worship of the Methodists and Baptists, the secret societies rose especially among the Free Negroes as a substitute for the primitive love of mystery. Practical insurance and benevolence, always a feature of such societies, were then cultivated. Of the organizations reported ninety-two were secret societies--some, branches or imitations of great white societies, some original Negro inventions.

Both the above organizations have efforts for social betterment as activities secondary to some other main object. There are, however, many Negro organizations whose sole object is to aid and reform. First among these come the beneficial societies. Like the burial societies among the serfs of the Middle Ages, there arose early in the Nineteenth century among Free Negroes and slaves, organizations which did a simple accident and life insurance business, charging small weekly premiums. These beneficial organizations have spread until to-day there are many thousands of them in the United States. They are mutual benefit associations and are usually connected with churches. Of such societies twenty-six are returned in this report.

Coming now to more purely benevolent efforts we have reported twenty-one organizations and institutions of various sorts which represent distinctly the efforts of the better class of Negroes to rescue and uplift the unfortunate and vicious. Finally, we have a few instances of co-operative business effort reported which typify the economic efforts of the weak to find strength in unity. Let us review each of the classes.

3. The Church.

The following table presents the returns of seventy-nine Negro churches in nine Southern cities; the queries sought to bring out especially the economic situation of these corporations, and their social and benevolent activity:

Page 6

| WASHINGTON, D. C. | NAME. | Denomination. | Enrolled Members. | Active Members. | Value of Real Estate. | Indebtedness. | Religious Meetings Weekly. | Entertainm'nts per year. | Lectures, Lit'ry Exercises pr yr | Suppers and Socials per year. | Fairs per year. | Concerts per year |

| 1 | Mt. Carmel | Baptist | 1,404 | 1,000 | $26,000 | $ 2,500 | 6 | 24 | 1 | |||

| 2 | Y. P. Tabernacle | Baptist | 40 | 40 | 7,000 | 750 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| 3 | Asbury | M. E. | 787 | 500 | 80,000 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 4 | Liberty | Baptist | 850 | 400 | 30,000 | 4 | ||||||

| 5 | Rehoboth | Baptist | 350 | 200 | 1,500 | 5 | 30 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 6 | Union | Baptist | 20 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| 7 | Grace Chapel | A. M. E. | 52 | 35 | 1,500 | 275 | 4 | 21 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| 8 | Northeastern | Baptist | 100 | 25 | 4 | 25 | 24 | 1 | ||||

| 9 | St. Luke. | Baptist | 300 | 150 | 10,000 | 140 | 5 | 40 | 1 | 20 | ||

| 10 | Rock Creek | Baptist | 300 | 160 | 1,000 | 100 | 4 | 30 | ||||

| 11 | 18th Street | Baptist | 1,500 | 800 | 80,000 | 10,000 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 5 | |

| 12 | Galbraith | AME, Z | 350 | 300 | 35,000 | 16,000 | 2 | |||||

| 13 | First W Washt'n | Baptist | 700 | 700 | 16,000 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 14 | Metropolitan | A. M. E. | 800 | 500 | 90,000 | 24,000 | 5 | 30 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| 15 | Virginia | Baptist | 400 | 350 | 17,000 | 3,400 | 4 | 50 | 13 | 25 | 2 | 10 |

| 16 | Shorter's Chapel | A. M. E. | 26 | 12 | 4,000 | 3 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 17 | M. Wesley | AME, Z | 500 | 200 | 50,000 | 7,500 | 5 | 20 | 50 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | Fifteenth Street. | Presby. | 312 | 160 | 60,000 | 7,000 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 19 | Berean | Baptist | 264 | 150 | 24,000 | 12,500 | 3 | |||||

| 20 | Macedonia | Baptist | 119 | 73 | 1,900 | 4 | 27 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 9 | |

| 21 | Campbell. | A. M. E. | 150 | 5,000 | 2,400 | 5 | 20 | |||||

| 22 | Miles Chapel | C. M. E. | 207 | 90 | 24,000 | 16,000 | 4 | |||||

| 23 | St. Luke's | P. E | 500 | 400 | 70,000 | 8,000 | 5 | 45 | 30 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| 24 | Metropolitan | Baptist | 700 | 450 | 65,000 | 25,000 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 25 | Plymouth | Congr'l | 227 | 158 | 25,000 | 5,000 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | ||

| 26 | Vermont Avenue | Baptist | 3,300 | 1,500 | 75,000 | 15,000 | 5 | 50 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| 27 | Israel | C.M.E. | 400 | 200 | 60,000 | 8,000 | 10 | 20 | 16 | 1 | 3 | |

| 28 | Ebenezer | M. E. | 784 | 500 | 50,000 | 20,000 | 9 | 47 | 2 | |||

| 29 | U. P. Temple | Congr'l | 100 | 100 | 3,000 | 8 | 15 | 50 | 3 | 2 | ||

| 30 | Third | Baptist | 975 | 450 | 40,000 | 17,000 | 3 | 50 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 31 | Mt. Zion. | M. E. | 650 | 550 | 27,500 | 2,800 | 22 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 4 | |

| 32 | Zion | Baptist | 2,139 | 45,000 | 12 | 24 | 5 | 12 | ||||

| 33 | Lincoln Mem. | Congr'l | 188 | 125 | 25,000 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| 34 | John Wesley | AME, Z | 265 | 150 | 75,000 | 15,000 | 5 | 50 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 35 | Our Redeemer. | Luther. | 50 | 30 | 9,000 | 6 | 40 | 40 | 2 | |||

| 36 | Bethlehem | Baptist | 145 | 75 | 2,500 | 3 | 6 | |||||

| 37 | Second | Baptist | 1,650 | 950 | 50,000 | 18,500 | 4 | 10 | 52 | 3 | 1 | |

| 38 | Shiloh | Baptist | 900 | 600 | 40,000 | 11,000 | 4 | 50 | 4 | PETERSBURG, VA. | ||

| 39 | St. Matthew | Baptist | 50 | 30 | $ 800 | $ 300 | 3 | 21 | 12 | 5 | 4 | |

| 40 | Zion | Baptist | 227 | 102 | 3,000 | 928 | 3 | 30 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 41 | Union Street | C.M.E. | 75 | 65 | 8,000 | 500 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| 42 | St. Stephen's | P. E. | 111 | 80 | 3,500 | 100 | 5 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| 43 | First | Baptist | 2,700 | 400 | 28,000 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 5 | |||

| 44 | Tabernacle | Baptist | 1,200 | 874 | 8,000 | 6 | ||||||

| 45 | Gilfield | Baptist | 2,612 | 1,996 | 35,360 | 3 | 12 | |||||

| 46 | Central | Presby. | 39 | 19 | 2,500 | 800 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 47 | Oak Street. | A. M. E. | 400 | 250 | 23,000 | 1,515 | 6 | 25 | 10 | 10 | 6 | |

| 48 | High Street. | Baptist | 80 | 60 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 49 | Bethany | Baptist | 100 | 75 | 600 | 257 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| 50 | Third | Baptist | 374 | 111 | 2,000 | 179 | 5 | 37 | 18 | 4 | 15 |

Page 7

| WASHINGTON, D. C. | ||||||||||||

| Other Entertainm'ts per yr. | No. of Church Organizations. | Literary Societies. | Benevolent Societies. | Missionary Societies. | Societies to aid Church. | Annual Income. | Annual Expense. | Expenditure for Charity. | Number of Persons Aided. | Work in Slums and Jails, etc. | REMARKS. | |

| 1 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | $ 2,406 | $ 2,406 | $288 | 10 | Two workers. | |||

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 700 | 700 | 20 | 6 | ||

| 3 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4,000 | 3,800 | 250 | Miss'n for jails. | |||

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 78 | 30 | ||||||

| 5 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 3,000 | 3,000 | |||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 75 | 50 | ||||||||

| 7 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 600 | 595 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 900 | 900 | |||||||

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1,060 | 1,060 | 100 | |||||||

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 100 | |||||||

| 11 | 2 | 20 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5,714 | 2,840 | 432 | Some. | ||

| 12 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3,000 | 3,000 | 200 | ||||

| 13 | 3 | 3 | *2,000 | 2,000 | 150 | Owns 2 tenements | 14 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10,000 | 9,000 | 226 | 50 | Some. | Has Asst. Pastor |

| 15 | 12 | 1 | 1,500 | 1,000 | 200 | 250 | Two churches have split off from this. | |||||

| 16 | 300 | 300 | 5 | Visits to slums. | ||||||||

| 17 | 25 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2,120 | 2,000 | 100 | 30 | |||

| 18 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

| 19 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2,480 | 2,200 | 180 | |||||

| 20 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 200 | 200 | 7 | 13 | Much work. | |

| 21 | 1,200 | 1,200 | ||||||||||

| 22 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2,087 | 2,000 | |||||||

| 23 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 500 | 120 | ||||

| 24 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3,900 | 4,160 | 75 | 25 | ||||

| 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,785 | 1,785 | 62 | 5 | Receives $300 a year from A. M. A. | ||||

| 26 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4,000 | 3,500 | 200 | Three workers. | |||||

| 27 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3,450 | 2,291 | 50 | 7 | Occasional. | ||||

| 28 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 4,926 | 4,926 | 75 | Much work. | ||||

| 29 | 5 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 1,500 | 1,500 | 50 | Much inst'l wk | ||||

| 30 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 84 | 36 | Occasional. | ||||

| 31 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3,000 | 2,800 | 140 | 25 | Some. | ||

| 32 | 11 | 1 | Mission. | |||||||||

| 33 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1,226 | 1,500 | 75 | 25 | Visits. | Receives $300 from A. M. A. | |

| 34 | 33 | 1 | 7 | 2,200 | 2,000 | 50 | 10 | |||||

| 35 | 2 | 2 | 400 | 600 | Receives aid. | |||||||

| 36 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 550 | 500 | 50 | Some. | ||||

| 37 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6,000 | 5,900 | 150 | $1.25 a piece usually given charity applic'nts | |||

| 38 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 4,500 | 4,425 | 400 | 100 | Seven workers. | PETERSBURG, VA. | |

| 39 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | $ 250 | $ | $ 10 | 30 | ||||

| 40 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 800 | 850 | ||||

| 41 | 1 | 1 | 300 | 350 | 10 | 5 | ||||||

| 42 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 492 | 664 | 12 | ||||||

| 43 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7,500 | 7,500 | 400 | Three missions | ||||

| 44 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1,231 | 1,130 | 378 | An orphanage. | |||||

| 45 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2,350 | 2,350 | ||||||

| 46 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 600 | 600 | 25 | 12 | 1 Missionary. | ||

| 47 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,000 | 900 | 50 | 25 | Mission. | Owns church, parsonage, mission house and tenement. | |

| 48 | 330 | 400 | ||||||||||

| 49 | 400 | 400 | 15 | 4 | ||||||||

| 50 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 400 | 400 |

* This probably does not include pastors' salary: the total income must be $4,000 or $5,000.

Page 8

| AUGUSTA, GA. | ||||||||||||

| Other Entertainm'ts per yr. | No. of Church Organizations. | Literary Societies. | Benevolent Societies. | Missionary Societies. | Societies to aid Church. | Annual Income. | Annual Expense. | Expenditure for Charity. | Number of Persons Aided. | Work in Slums and Jails, etc. | REMARKS. | |

| 51 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | $ 3,000 | $ 2,400 | $ 3 | Irregular | ||||

| 52 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 125 | 89 | ||||

| 53 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 50 | |||||

| 54 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 50 | 20 | BOWLING GREEN, KY. | ||||

| 55 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | $ 500 | $ 450 | $ 7 | 6 | Some. | |||

| 56 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 800 | 900 | 10 | 5 | ||||

| 57 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1,300 | 1,000 | 20 | 15 | MOBILE, ALA. | ||

| 58 | 6 | $ 1,500 | $ 1,400 | $600 | 75 | Visits. | ||||||

| 59 | 1 | 4 | 6,214 | 6,214 | 387 | 200 | Twelve visits. | Value par. $1,500; organ, $1,000. | ||||

| 60 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2,000 | 1,900 | 125 | ||||

| 61 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 425 | 425 | 25 | 10 | $300 from A.M.A. | FORT SMITH, ARK. | ||

| 62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | $ 1,059 | $ 1,059 | $150 | 25 | |||

| 63 | 1 | 1 | 982 | 980 | 42 | 10 | ||||||

| 64 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1,300 | 1,300 | 75 | GALVESTON, TEX. | |||||

| 65 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | $ 1,200 | $ 1,200 | $300 | 10 | Eight visits. | |||

| 66 | 2 | 1 | 1,250 | 1,230 | 150 | 75 | Visit hospitals. monthly. | |||||

| 67 | 1 | 1 | 1,600 | 1,600 | ||||||||

| 68 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,550 | 1,500 | 300 | 125 | Ten visits | Parish school. | CLARKESVILLE, TENN. | |

| 69 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | $ 2,000 | $ 2,000 | $ 75 | 15 | ATLANTA, GA. | ||

| 70 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | $ 2,000 | $ 1,800 | $200 | 20 | Some. | Publishes paper. | |

| 71 | 2,046 | 19 | Some. | One mission. | ||||||||

| 72 | 1 | 3,000 | 1500 | Some. | Two missions and Home for Aged. | |||||||

| 73 | 1 | 6,000 | 80 | |||||||||

| 74 | 2,300 | 25 | ||||||||||

| 75 | 2,920 | 45 | ||||||||||

| 76 | 700 | 14 | ||||||||||

| 77 | 1,242 | 17 | ||||||||||

| 78 | 3,002 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 79 | 203 | 66 |

Page 9

| AUGUSTA, GA. | NAME. | Denomination. | Enrolled Members. | Active Members. | Value of Real Estate. | Indebtedness. | Religious Meetings Weekly. | Entertainm'nts per year. | Lectures. Lit'ry Exercises pr yr | Suppers and Socials per year. | Fairs per year. | Concerts per year. |

| 51 | Trinity | C.M.E. | 850 | 850 | $ 7,850 | 3 | 1 | 12 | ||||

| 52 | Bethel | A. M. E. | 500 | 200 | 20,000 | 3,600 | 8 | 37 | 10 | 12 | 10 | |

| 53 | Union | Baptist | 325 | 217 | 15,000 | 3,500 | 15 | |||||

| 54 | Central | Baptist | 656 | 200 | 15,000 | 150 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 4 | BOWLING GREEN, KY. |

| 55 | College Street | C. Pres. | 130 | 74 | $ 2,800 | $ | 4 | 5 | ||||

| 56 | Taylor's Chapel | A. M. E. | 183 | 120 | 5,000 | 800 | 4 | 25 | 8 | 7 | 10 | |

| 57 | State Street | Baptist | 850 | 600 | 1,500 | 4 | 24 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | MOBILE, ALA. |

| 58 | Zion | A. M. E. | 750 | 650 | $ 7,450 | $ 700 | 5 | 3 | 12 | |||

| 59 | State Street | AME, Z | 1,000 | 800 | 18,000 | 4 | 5 | 52 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 60 | Bethel. | A. M. E. | 420 | 300 | 5,000 | 75 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| 61 | First. | Congr'l | 125 | 100 | 3,000 | 3 | 12 | 1 | FORT SMITH, ARK. | |||

| 62 | I. W. Burns | C.M.E. | 140 | 75 | $ 2,000 | 7 | 25 | 52 | 19 | 1 | 6 | |

| 63 | Mallallieu | M. E. | 142 | 92 | 1,200 | 3 | 10 | 12 | ||||

| 64 | Quinn Chapel | A. M. E. | 250 | 200 | 5,000 | 2 | GALVESTON, TEX. | |||||

| 65 | Macedonia | Baptist | 500 | 250 | $ 7,000 | $ 150 | 4 | 24 | 24 | 5 | ||

| 66 | Reedy Chapel | A. M. E. | 427 | 304 | 20,000 | 1,207 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 5 | |

| 67 | Frank Gary | M. E. | 300 | 200 | 9,500 | 6 | 24 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 68 | St. Augustine | P. E. | 300 | 185 | 13,000 | 2,200 | 3 | 3 | 2 | CLARKESVILLE, TENN. | ||

| 69 | St. Peter's Chap. | A. M. E. | 323 | 225 | $20.000 | $ 263 | 6 | 6 | 24 | 4 | ATLANTA, GA. | |

| 70 | First. | Congr'l | 400 | 300 | $10,000 | $ 100 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 1 | |

| 71 | Wheat Street. | Baptist | 1,692 | |||||||||

| 72 | Friendship | Baptist | 1,570 | |||||||||

| 73 | Bethel | A. M. E. | 1,350 | |||||||||

| 74 | Lloyd Street. | M. E. | 800 | |||||||||

| 75 | Allen Temple. | A. M. E. | 595 | |||||||||

| 76 | Reed Street | Baptist | 460 | |||||||||

| 77 | Providence | Baptist | 391 | |||||||||

| 78 | Shiloh | Baptist | 230 | |||||||||

| 79 | New Hope. | Presby. | 100 |

Page 10

This table may be summarized as follows:

| Number of Churches reported | 79 |

| Number of Denominations reported | 9 |

| Baptist | 37 Churches. |

| Methodists: | |

| African Methodist Episcopal | 14 |

| African Methodist Episcopal Zion | 4 |

| Colored Methodist Episcopal | 5 |

| Methodist Episcopal | 6--29 Churches. |

| Congregational | 5 Churches. |

| Presbyterian | 4 Churches. |

| Protestant Episcopal | 3 Churches. |

| Lutheran | 1 Churches. |

| Total enrolled members | 42,631 |

| Active members, less than | 30,000 |

| Value of real estate owned, 67 churches reporting | $1,542,460 00 |

| Reported indebtedness | 295,114 00 |

| Total annual income | 157,678 00 |

| Total recorded expenditure in local charity (65 churches reporting) | 8,906 68 |

| Number of missionary and benevolent societies reported | 123 |

| Number of persons directly aided so far as reported (36 churches) | 1,422 | GENERAL BENEVOLENT AND REFORMATORY ACTIVITY. |

| Some irregular work in slums, jails, etc | 8 Churches. |

| Considerable irregular work in slums, jails, etc | 2 Churches. |

| 1 mission established in slums. | 3 Churches. |

| 3 missions established in slums | 1 Churches. |

| Regular visits to slums | 3 Churches. |

| Mission for jails | 1 Churches. |

| 2 regular workers in missionary and benevolent work | 1 Churches. |

| 1 regular worker | 1 Churches. |

| 3 regular workers | 1 Churches. |

| 7 regular workers | 1 Churches. |

| Regular institutional work | 1 Churches. |

| 8 visits a year | 1 Churches. |

| 12 visits a year | 1 Churches. |

| 10 visits a month and parish school. | 1 Churches. |

| Visits to hospitals with food | 1 Churches. |

| Orphanage | 1 Churches. |

| Home for aged and two missions | 1 Churches. |

| Total | 29 Churches. |

Page 11

These returns do not give an account of all of the benevolent work of Negro Churches; much is done by individuals, and perhaps the larger part of the charity is entirely unsystematic and no record is kept of it. Some needy person or cause appeals to a congregation. Immediately in a whirl of sympathy or enthusiasm a collection is taken up and the money given, although no official record remains of the deed. So, too, the distress of the needy is often relieved by neighbors through notices given in the church. While, then, these returns do not indicate the whole benevolent activity of churches, yet they do give an idea of the orderly systematic work of the more business-like organizations.

A better idea of the activity of Negro Churches will be obtained, perhaps, if we tabulate the income and charitable expenditure of such churches as give $100 or more annually in charity.

| No. | PLACE. | DENOMINATION. | Annual income. | Annual expenditure in charity. | Per cent. of Income expended in charity. |

| 1 | *Atlanta. | Baptist | $ 3.000 | $1,500 | 50. |

| 2 | Mobile | Methodist | 1,500 | 600 | 40. |

| 3 | Petersburg | Baptist | 1,231 | 378 | 30 |

| 4 | Galveston | Baptist | 1,200 | 300 | 25. |

| 5 | Galveston | P. E | 1,550 | 300 | 19. |

| 6 | Washington | P. E | 3,500 | 500 | 14. |

| 7 | Fort Smith | Methodist | 1,059 | 150 | 14. |

| 8 | Washington | Baptist | 1,500 | 200 | 13. |

| 9 | Galveston | Methodist | 1,250 | 150 | 12. |

| 10 | Washington | Baptist | 2,406 | 288 | 12. |

| 11 | Washington | Baptist | 1,060 | 100 | 10. |

| 12 | Washington | Baptist | 1,000 | 100 | 10. |

| 13 | Atlanta | Congregational | 2,000 | 200 | 10. |

| 14 | Washington | Baptist | 4,500 | 400 | 9. |

| 15 | Washington | Baptist | 3,000 | 150 | 7.5 |

| 16 | Washington | Baptist | 5,714 | 432 | 7.5 |

| 17 | Washington | Baptist | 2,480 | 180 | 7.2 |

| 18 | Washington | Methodist | 3,000 | 200 | 6.6 |

| 19 | Mobile | Methodist | 6,215 | 388 | 6.3 |

| 20 | Washington | Methodist | 4,000 | 250 | 6.2 |

| 21 | Mobile | Methodist | 2,000 | 125 | 6.2 |

| 22 | Petersburg | Baptist | 7,500 | 400 | 5.3 |

| 23 | Washington | Baptist | 4,000 | 200 | 5. |

| 24 | Washington | Methodist | 2,000 | 100 | 5. |

| 25 | Washington | Methodist | 3,000 | 140 | 4.7 |

| 26 | Washington | Baptist | 6,000 | 150 | 2.5 |

| 27 | Washington | Methodist | 10 000 | 226 | 2.2 |

* This church is building a Home for the Aged, so that this is extraordinary expenditure.

--Nineteen other churches give between $50 and $100 a year, and thirty-three churches either give less than $50 or make no returns. Probably most of these give considerable in an unsystematic way.

Some individual churches present noticeable peculiarities. One Congregational Church "is doing a varied work along institutional lines." In

Page 12

a Methodist Church "the Wayside Gatherers have a mission for assisting the denizens of slums and jails." Another Methodist Church has "a committee to visit the jail every week." A Baptist Church has the interest from a fund, amounting to $150 each year, set aside for the poor; "We only give them enough to buy medicines and, at times, fuel, never appropriating more than $1.25 to each." Another large Baptist Church, with 800 active members, reports a detailed budget:

| 1895. | |||

| Total income | $5,714.09 | Total expense: Build'g and improvements | $2,840 00 |

| Sunday-school Charity: | 132 00 | ||

| Church poor | $236 00 | ||

| Educat'n of Min'strs | 32 52 | ||

| Missions | 30 14 | ||

| Miscellaneous. | 134 00 432 66 | ||

| Pastor's salary and other church expenses | 1,871 77 | ||

| Balance on hand | 437 66 | ||

| $5,714 09 |

One Baptist Church in Petersburg, Va., conducts an orphanage, and another in Atlanta is erecting a home for the aged at a cost of $6,000. Whites have contributed considerably to this latter enterprise, but much of it has been done by Negroes.

From this data it is clear that Negro Churches are becoming centres of systematic relief and reformatory work of Negroes among themselves. At present the actual expenditure of the organized agencies is not large compared with the income of the churches; but when we remember that the members of these churches are largely poor working people, with little business training, and that much of the unorganized and spasmodic work is unrecorded it seems that the work being done is both commendable and by no means insignificant in amount.

4. The Secret Society.

--Ninety-two lodges, belonging to nine different secret societies, were reported, although these by no means cover all existent lodges in the cities studied. Those reporting were:

| Grand United Order of Odd Fellows | 38 Lodges. |

| Ancient Order of Free and Accepted Masons | 13 Lodges. |

| Grand United Order of True Reformers | 12 Fountains. |

| International Order of Good Samaritans, etc | 8 Unions. |

| J. R. Giddings and Jollifee Union | 8 Tents. |

| Independent Order of St. Luke | 7 Councils. |

| Ancient Sons, etc., of Israel | 3 Tabernacles. |

Page 13

| Knights of Pythias | 2 Lodges. |

| Knights of Tabor | 1 Lodge. |

| 9 Orders | 92 Organizations. |

Of these the Odd Fellows, Masons and Knights of Pythias are simliar organizations to those among white people but are not directly affiliated with them. The Negro Masons of the United States, for instance, sprung from a lodge of Boston Negroes who received their charter from England. Most of the other orders seem to be Negro inventions purely, and form curious and instructive organizations. Their main function is insurance against. sickness and death, the aiding of the widows and orphans of their deceased members, and social intercourse. Their activity and condition in detail is given in Table II.

Page 14

| PLACE. | NAME. | ORDER. | Members. | Active Members. | Investments in Real Estate and other Property. | Cash on Hand. | Total Annual Income. | Source Thereof. | Total Sick Benefits. | Total Death Benefits | No. of Persons Aided. |

| Washington, D. C. | Peter Ogden | Odd Fellows. | 112 | 102 | $ 1,040 00 | $250 00 | $ | Dues. | $175 00 | $275 00 | 10 |

| Washington, D. C. | Star of the West | Odd Fellows. | 84 | 69 | 1,000 00 | 23 00 | Dues. | 277 00 | 256 25 | 12 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Bloom of Youth | Odd Fellows. | 102 | 87 | 12,000 00 | 150 00 | Dues. | 133 00 | 207 00 | 17 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Rising Sun | Odd Fellows. | 76 | 68 | 500 00 | 147 00 | Dues. | 901 00 | 195 00 | 16 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Free Grace | Odd Fellows. | 109 | 100 | 14 20 | 694 00 | Dues. | 146 46 | 310 07 | 16 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Mount Olive | Odd Fellows. | 85 | 75 | 14 46 | 81 00 | Dues. | 218 80 | 237 00 | 33 | |

| Washington, D. C. | John F. Cook | Odd Fellows. | 78 | 49 | 607 07 | 71 00 | Dues. | 101 15 | 208 00 | 12 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Eastern Star | Odd Fellows. | 68 | 41 | 870 09 | 391 00 | Dues. | 77 00 | 147 00 | 17 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Potomac Union | Odd Fellows. | 90 | 64 | 326 27 | 59 00 | Dues. | 324 00 | 191 00 | 5 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Union Friendship | Odd Fellows. | 70 | 62 | 880 00 | 333 00 | Dues. | 45 05 | 90 00 | 11 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Progressive Lodge | Odd Fellows. | 55 | 55 | 228 00 | Dues. | |||||

| Washington, D. C. | Corinthian. | Odd Fellows. | 58 | 38 | 96 00 | Dues. | 75 50 | 147 40 | |||

| Washington, D. C. | Golden Reef | Odd Fellows. | 71 | 60 | 909 90 | 148 00 | Dues. | 12 00 | 15 00 | 3 | |

| Washington, D. C. | A. K. Manning | Odd Fellows. | 95 | 77 | 800 00 | Dues. | 78 00 | 80 00 | 14 | ||

| Washington, D. C. | Traveling Pilgrim | Odd Fellows. | 33 | 20 | 105 00 | 34 00 | Dues. | 23 50 | 5 | ||

| Washington, D. C. | W. A. Freeman | Odd Fellows. | 107 | 93 | 1,769 00 | 451 00 | Dues. | 171 00 | 237 00 | 18 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Osceola | Odd Fellows. | 78 | 69 | 275 00 | 12 00 | Dues. | 75 00 | 39 00 | 11 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Union Light | Odd Fellows. | 70 | 60 | 700 00 | 192 00 | Dues. | 99 05 | 71 15 | 9 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Social | Odd Fellows. | 89 | 81 | 900 00 | 220 00 | Dues. | 117 05 | 120 00 | 15 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Rose Hill | Odd Fellows. | 73 | 70 | 338 40 | 88 14 | Dues. | 45 25 | 177 25 | 8 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Old Ark | Odd Fellows. | 136 | 128 | 1,509 45 | 115 00 | Dues. | 281 22 | 44 75 | 14 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Simon | Odd Fellows. | 120 | 105 | 600 00 | Dues. | 207 85 | 180 00 | 27 | ||

| Washington, D. C. | Green Mountain | Odd Fellows. | 102 | 79 | 1,000 00 | 128 00 | Dues. | 289 74 | 98 03 | 11 | |

| Washington, D. C. | J. McCrummell | Odd Fellows. | 107 | 75 | 100 00 | 45 00 | Dues. | 195 85 | 237 00 | 19 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Western Star | Odd Fellows. | 47 | 42 | 378 30 | 245 00 | Dues. | 96 65 | 100 00 | 11 | |

| Washington, D. C. | Columbia | Odd Fellows. | 57 | 52 | 700 00 | 93 00 | Dues. | 64 71 | 120 00 | 2 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | Taylor's Fountain | True Reformers | 43 | 43 | 180 60 | Dues & asses | 12 50 | 10 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Christoe's Fountain | True Reformers | 18 | 15 | 90 00 | Dues. | 12 00 | 4 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Cedar Leaf | True Reformers | 32 | 29 | 160 00 | Dues & asses | 16 00 | 14 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Sheba Lodge | Masons. | 45 | 30 | 700 00 | 100 00 | Dues. | 10 00 | 6 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Virginia Lodge | Masons. | 15 | 16 | 300 00 | 30 00 | 5 00 | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Bethel | True Reformers | 47 | 47 | 195 87 | Dues & taxes | 20 50 | 9 |

Page 15

| PLACE. | NAME. | ORDER. | Members. | Active Members. | Investments in Real Estate and other Property. | Cash on Hand. | Total Annual Income. | Source Thereof. | Total Sick Benefits. | Total Death Benefits | No. of Persons Aided. |

| Petersburg, Va. | Gethsemane | Giddings | 45 | 45 | $ | $ | $163 80 | Dues & taxes | $ 12 00 | 3 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | Keystone Fountain | True Reform'rs | 72 | 72 | 350 00 | Dues & taxes | 77 00 | $375 00 | 23 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Green Bay | St. Luke | 45 | 43 | 154 80 | Dues & taxes | 6 00 | 2 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Friendly. | Masons | 17 | 15 | 45 00 | Dues & taxes | |||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Mt. Olive | True Reform'rs | 16 | 16 | 80 00 | Dues. | 20 00 | 8 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | H. O. Johnson. | Samaritans | 10 | 10 | 29 42 | 30 80 | Dues & taxes | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Sarah's | Giddings | 39 | 38 | 85 15 | Dues. | 19 50 | 2 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | St. James | Israel. | 20 | 20 | 60 00 | Dues. | 4 50 | 3 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Jerusalem | Masons | 30 | 30 | 500 00 | 135 00 | Dues. | 24 00 | 60 00 | 8 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | Pocahontas | Masons | 18 | 18 | 750 00 | 50 00 | Rent & dues | 10 00 | 30 00 | 2 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | Abraham | Masons | 19 | 19 | 500 00 | 119 50 | Dues | 27 75 | 60 00 | 5 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | United Sons of the Morning. | Odd Fellows. | 84 | 76 | 1,400 00 | 320 00 | Dues & rents | 102 50 | 50 00 | 18 | |

| Petersburg, Va. | Mahala's | Giddings | 16 | 16 | 55 00 | Dues & taxes | 20 00 | 1 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Leah's | Giddings | 28 | 28 | 87 36 | Dues. | 12 00 | 5 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Shiloh Rosebud | True Reform'rs | 19 | 19 | 37 61 | Dues. | 29 00 | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Rose Bud Fountain. | True Reform'rs | 26 | 26 | 45 00 | Dues & taxes | 21 20 | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Rosebuds | True Reform'rs | 14 | 14 | 42 00 | Dues. | 15 80 | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Randolph | True Reform'rs | 96 | 96 | 340 29 | Dues. | 60 00 | 250 00 | 20 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | King Solomon's | Israel. | 42 | 42 | 130 20 | Dues. | 21 00 | 7 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Samuel's | Israel. | 28 | 28 | 86 80 | Dues. | 6 00 | 2 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Abigail Tent | Giddings | 25 | 25 | 66 00 | Dues. | 5 50 | 3 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Mt. Ararat | St. Luke | 21 | 21 | 78 02 | Dues. | 8 50 | 5 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Charity | Samaritans | 30 | 30 | 300 00 | 100 00 | Dues & fines | 40 00 | 75 00 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Eureka | St. Luke. | 23 | 23 | 82 80 | Dues & fines | 7 60 | 4 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Mt. Lebanon | St. Luke. | 15 | 15 | 60 20 | Dues. | 1 00 | 14 55 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | St. Mary's | St. Luke. | 20 | 20 | 72 00 | 18 00 | 20 00 | 7 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Mt. Carmel | St. Luke. | 19 | 19 | 70 68 | Dues & fines | 10 00 | 45 00 | 5 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Sheba. | St. Luke. | 16 | 16 | 57 60 | Dues & fines | 4 50 | 3 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | St. Joseph | Odd Fellows. | 57 | 57 | 2,800 00 | 196 00 | Dues & fines | 28 50 | 6 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Roxeillas | Giddings | 23 | 23 | 74 40 | Dues & fines | 10 50 | 10 00 | 4 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Hannah | Giddings | 35 | 35 | 113 40 | Dues & fines | 22 00 | 9 | |||

| Petersburg, Va. | Shiloh | True Reform'rs | 53 | 53 | 265 00 | Dues & fines | 19 57 | 37 73 | 2 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Dinwiddie | True Reform'rs | 34 | 34 | 170 00 | 27 00 | 15 | ||||

| Petersburg, Va. | Queen Esther. | Giddings | 41 | 35 | 105 00 | Dues & fines | 25 00 | 80 00 | 15 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Eureka | Masons | 25 | 20 | 200 00 | 95 00 | 50 00 | 75 00 | 10 | ||

| Petersburg, Va. | Weldone | Odd Fellows. | 18 | 18 | 90 00 | Dues & fines | 15 00 | 4 | |||

| Fort Smith, Ark. | Knight of Tab'r | 81 | 81 | 400 00 | 300 00 | Dues, picnic | 91 73 | 120 00 | |||

| Fort Smith, Ark. | Widow's Son | Masons | 52 | 40 | One lot | 300 00 | Rent, etc. | 300 00 | 200 00 | 4 | |

| Fort Smith, Ark. | Matier. | Odd Fellows. | 52 | 49 | 3,000 00 | 800 00 | Dues. | 200 00 | 100 00 | 25 |

Page 16

| PLACE. | NAME. | ORDER. | Members. | Active Members. | Investments in Real Estate and other Property. | Cash on Hand. | Total Annual Income. | Source Thereof. | Total Sick Benefits. | Total Death Benefits. | No. of Persons Aided. |

| Mobile, Ala. | Crystal Fountain | Samaritans | 580 | 580 | $9,000 00 | $ | $2,700 00 | Dues. | $630 00 | $500 00 | |

| Mobile, Ala. | Garrison | ||||||||||

| Mobile, Ala. | Golden Gate | ||||||||||

| Mobile, Ala. | Sparkling Water | ||||||||||

| Mobile, Ala. | Star of Hope | ||||||||||

| Mobile, Ala. | Ark of Safety | ||||||||||

| Mobile, Ala. | Tompkins | ||||||||||

| Odd Fellows | 300 | 300 | 50 00 | 1,260 00 | Dues. | 300 00 | Mobile, Ala. | Bethel | |||

| K. of P | 56 | 40 | 150 00 | Dues, picnic | 36 00 | 12 | Clarkesville, Tenn. | Mt. Vernon | |||

| Odd Fellows | 35 | 29 | 500 00 | 210 00 | Dues. | 48 00 | 7 | Bowling Green, Ky | Mt. Calvary | ||

| Odd Fellows | 27 | 19 | 400 00 | 150 00 | Dues. | 20 00 | 4 | Atlanta, Ga. | Rising Sun | ||

| Masons | 75 | 75 | 900 00 | 250 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | Crystal | ||||

| Masons | 80 | 25 | 150 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | Rising Sun | |||||

| Masons | 80 | 50 | 50 00 | Dues. | 20 00 | 15 00 | Atlanta, Ga. | Richard Allen | |||

| Knights of P. | 60 | 50 | Dues. | 50 00 | Atlanta, Ga. | Plymouth | |||||

| Masons | 40 | 37 | 240 00 | Dues. | 16 50 | 3 00 | Atlanta, Ga. | St. James, No. 4 | |||

| Masons | 62 | 37 | 325 00 | Dues. | 10 00 | 3 00 | Atlanta, Ga. | Star of the South | |||

| Odd Fellows. | 65 | 60 | 360 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | Pride of Georgia | |||||

| Odd Fellows. | 175 | 165 | One lot | 990 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | St. James. | ||||

| Odd Fellows. | 140 | 130 | 780 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | Fulton Enterprise | |||||

| Odd Fellows. | 160 | 140 | 840 00 | Dues. | Atlanta, Ga. | Love of Freedom. | |||||

| Odd Fellows. | 72 | 65 | 390 00 | Dues. |

Page 17

A summary of this table can be made as follows:

| Total membership | 5,763 |

| Active membership | 5,150 |

| Total value of investments in real estate and other property | *$49,073 05 |

| Total cash on hand | 4,651 40 |

| Annual income | 16,060 62 |

| Annual Expenditure: | |

| For sick benefits | $6,960 98 |

| For death benefits | 5,934 78 $12,895 76 |

| Total numbr of persons aided last year | 612. |

* Plus two unvalued lots.

Some facts about certain societies are of interest: One lodge of the Giddings Order in Petersburg, Va., has been organized 23 years, and is composed entirely of women; another lodge in the same place describes its work as consisting of "relief given to widows and children, and the education of minors." One lodge of Masons in the same place was organized in 1867, and a lodge of Odd Fellows in 1866. Of a lodge of Masons in Clarkesville, Tenn., it is said: "Most of the members own their own homes;" the lodge has spent "$10,000 for burials and sick dues since organization," September 28, 1874, or an average of over $700 a year. They own a lot and expect to build a hall on it soon. Another Petersburg lodge of the Giddings Union assesses each member $1 a year to support an Old Folks' Home for the general order. One Odd Fellows' Lodge in Mobile has been organized fifty-five years, that is, since 1843. Both Masons and Odd Fellows in Fort Smith. Ark., own halls, two stories in height, with stores below, which are rented out.

We have here a kind of an organization which contrasts sharply with the churches, considered as business enterprises. First, it demands a higher average of intelligence and thrift in its membership, and more quiet, business-like persistence along selected lines of effort. The process of social selection has consequently made the group much smaller than the church organization, averaging fifty and sixty members, and having in no case over 175 members. These smaller and more compact groups do not handle as much money as the churches, but by arranging regular sources of income and carefully calculating expenses they use their funds more effectively. The secrecy and ritual of these lodges is not without a certain social value. It attracts members, and then, too, it allows the establishment of a hierarchy of authority, which does away, to some extent, with the democratic freedom of the church; thus the more competent (and at times, it must be confessed, more unscrupulous), get a chance to guide and rule. The main practical objects of these societies are life and sickness insurance, and social intercourse. They represent the saving, banking spirit among the Negroes and are the germ of commercial enterprise of a purer type.

On the other hand, the secret societies represent much extravagance and waste in expenditure, an outlay for regalia and tinsel, which too often lack the excuse of being beautiful, and to some extent they divert the savings of Negroes from more useful channels.

Page 18

5. Beneficial and Insurance Societies.

--The beneficial society sprang directly from the church organizations and has developed in four characteristic directions. First, by taking on ritual, oaths and secrecy it became the secret society just mentioned. Secondly, by emphasizing and enlarging the beneficial and insurance feature and substituting a board of directors for general membership control, many of these societies coalesced into, or were replaced by, insurance societies. Thirdly, the training in business methods thus received is now, in an increasing number of cases leading to co-operative business enterprise. Fourthly, the distribution of aid and succor tended to pass beyond the immediately contributing members, and become pure charity in the shape of Homes, Asylums and Benevolent Societies of various sorts.

In number of organizations the secret societies outstripped the benevolent societies, while the others naturally are still but partially developed. Nevertheless the beneficial society antedates emancipation; some now in existence are fifty years old or more, and others now extinct can be traced back to the Eighteenth century.

These societies, of all kinds, sizes and states of efficiency, are still very numerous. Take, for instance, Petersburg, Va. There alone we have reports from twenty-two, as follows:

| NAME. | When Organized. | No. Members | Assessments per Year. | Total Annual Income. | Sick and Death Benefits. | Cash and Property. | |

| 1 | Young Men's | 1884 | 40 | $7 00 | $ 275 00 | $ 150 00 | $ 175 00 |

| 2 | Sisters of Friendship, etc.* | 22 | 3 00 | 68 55 | 43 78 | ||

| 3 | Union Working Club | 1893 | 15 | 3 00 | 45 00 | 23 00 | |

| 4 | Sisters of Charity | 1884 | 17 | 3 00 | 51 00 | 30 00 | |

| 5 | Ladies' Union | 1896 | 47 | 3 00 | 135 00 | 128 25 | |

| 6 | Beneficial Association | 1893 | 163 | *25c. 5 20 | 1,005 64 | 808 46 | 440 00 |

| 7 | Daughters of Bethlehem | 39 | *12c. 3 00 | 129 48 | 110 04 | ||

| 8 | Loving Sisters | 1884 | 16 | *25c. 3 00 | 22 50 | 30 50 | 62 00 |

| 9 | Ladies' Working Club | 1888 | 37 | *12c. 3 00 | 95 11 | 52 65 | 214 09 |

| 10 | St. Mark. | 1874 | 28 | *12c. 3 00 | 84 00 | 32 00 | 150 00 |

| 11 | Consolation | 1845 | 26 | *12c. 3 00 | 68 00 | 27 00 | 100 00 |

| 12 | Daughters of Zion | 1867 | 22 | *12c. 3 00 | 66 00 | 40 00 | 36 00 |

| 13 | Young Sisters of Charity. | 1869 | 30 | *12c. 3 00 | 90 00 | 30 00 | 100 00 |

| 14 | Humble Christian | 1868 | 26 | *12c. 3 00 | 68 00 | 35 50 | 75 00 |

| 15 | Sisters of David | 1885 | 30 | 3 00 | 90 00 | 60 00 | 120 00 |

| 16 | Sisters of Rebeccah | 1893 | 40 | 3 00 | 120 00 | 85 00 | 175 00 |

| 17 | Petersburg | 1872 | 29 | *12½c. 3 00 | 85 00 | 11 00 | 99 53 |

| 18 | Petersburg Beneficial | 1892 | 35 | *50c. 5 20 | 182 00 | 158 00 | 118 00 |

| 19 | 1st Baptist Church Ass'n | 1893 | 100 | 60 | 60 00 | 40 00 | 80 00 |

| 20 | Young Men's | 1894 | 44 | *25c. 3 00 | 211 00 | 202 25 | 100 00 |

| 21 | Oak St. Church Society | 1894 | 38 | 1 20 | 42 60 | 112 63 | 50 00 |

| 22 | Endeavor, etc | 1894 | 98 | 3 00 | 120 00 | 96 00 | 43 00 |

| Total | 942 | $3,113 88 | $2,177 81 | $2,275 87 |

* Organized before the war.

*Assessment upon each member in case any member dies.

Page 19

Returns from other places are not so full, not because of the lack of such societies, but because of the difficulty of getting exact reports from them. They are small, have no public office and must be searched for. Probably there are at least one hundred such societies in the nine cities. Some are small and weak, others flourishing. Of the latter class the condition of six typical ones is given in the next table.

| PLACE. | NAME. | When Organized. | Number Members. | Assessments per Year. | Total Annual Income. | Sick and Death Benefits. | Cash and Property. |

| Galveston, Tex | Daughters of Rebecca | 1866 | 53 | $ 12 00 | $ 900 | $ 800 | $3,000 |

| Augusta, Ga. | Trinity Moral Reform | 1850 | 240 | 1 00 | 960 | 500 | 100 |

| Augusta, Ga. | Union Relief | 1894 | 100 | 1 20 | 800 | 300 | 1,000 |

| Augusta, Ga. | Young Mutual | 1886 | 475 | 661 | 498 | 87 | |

| Atlanta, Ga | Helping Hand | 1879 | 50 | 140 | 100 | 1 lot. | |

| Atlanta, Ga | Coachman's Benefit | 1896 | 40 | 240 | |||

| Six Societies | 958 | $3,701 | $2,198 | $4,187 |

The business methods of beneficial societies are extremely simple. A group of mutually known persons, members of the same church or neighbors, unite in an organization and agree to pay weekly 25 cents or more into a common treasury; a portion of the fund thus secured is paid to any member who may be taken sick, and, too, the other members in such case give their services in caring for the sick one. In case a member dies each of the other members is assessed from 12½ to 50 cents--usually 25 cents--in addition to their regular fee, to help defray funeral expenses. This simple and safe insurance business has everything to commend it as a method of self-help, and it has without doubt had much to do with the social education of the Negro, both before and since emancipation.

The indications are that ten or fifteen years ago the number of these societies was twice as great as at present. Over half of those reported in this inquiry were established before 1890, and are probably survivals of a very large number of enterprises. The insurance societies have come in to replace the activities of these societies, and the change, while indicating higher economic development, is at present having many disastrous results. The impulse towards insurance societies was given by the large number of white societies organized to defraud and exploit the Negroes. Everywhere the Freedman is noted for his effort to ward off accident and a pauper's grave by insurance against sickness and death. In New York city a canvass of one slum district showed that 15% of the Negro fathers and 52% of the mothers

belonged to insurance societies.* *Laidlaw, 2nd Sociological Canvass, 1897. *DuBois, The Philadelphia Negro.

In Philadelphia the situation is similar, although the disparity between the sexes is not so great.*

So, too, throughout the South the operations of these societies has been wide-spread. Partly in self-defence therefore,

Page 20

and partly in obedience to a natural desire to unite small economic efforts into larger, the Negro insurance societies began to arise about 1890, and now have throughout the country a membership running into the hundred thousands. Some of the secret societies are in reality insurance societies with a ritual to make membership more attractive. The True Reformers' order, for instance, was started in Richmond, Va., not over fifteen years ago; it now extends widely over the East and South, owns considerable real estate and conducts a banking and annual premium insurance business at Richmond.

Three typical Virginia insurance societies are the Workers' Mutual Aid Association, the Colored Mutual Aid Association and the United Aid and Insurance Company. The Workers' Mutual Aid Association was organized in 1894. It is conducted by twelve stockholders and has two salaried officers, besides the agents. It claims 10,053 members, an annual income of $3,600, and sick and death benefits paid during the year to the amount of $1,700. It owns property to the amount of $550. Its rates of insurance are as follows:

| Weekly Premiums. | Weekly Sick Benefits. | Death Benefits. |

| $ 05 | $1 25 | $ 17 00 |

| 10 | 2 00 | 35 00 |

| 15 | 2 75 | 45 00 |

| 20 | 3 50 | 55 00 |

| 25 | 4 25 | 65 00 |

| 30 | 5 00 | 75 00 |

| 35 | 5 75 | 85 00 |

| 40 | 6 50 | 95 00 |

| 45 | 7 25 | 105 00 |

| 50 | 8 00 | 115 00 |

The agent reporting declares: "This class of enterprises do well, but the great drawback is they are too numerous, and it is hard to find young men who are willing to do the work necessary to make them a success; and then the class who are willing to take hold honestly, is at a very grea premium." The headquarters of this association is in Petersburg, Va.

The Colored Mutual Aid Association was organized in 1895; the number of stockholders is sixteen; the number of salaried officers, three; the number of members, 5,000; the total annual income, $1,172 82; the total expenditures for sick and death benefits, $800. The rates of insurance are:

| Weekly premiums. | Weekly Sick Benefits. | Death Benefits. |

| $ 05 | $ 1 50 | $ 15 00 |

| 10 | 3 25 | 35 00 |

| 15 | 3 50 | 40 00 |

| 20 | 4 50 | 50 00 |

| 25 | 5 25 | 60 00 |

| 30 | 6 00 | 75 00 |

| 35 | 7 00 | 85 00 |

| 40 | 8 00 | 95 00 |

| 45 | 9 00 | 100 00 |

| 50 | 10 00 | 115 00 |

Page 21

The United Aid and Insurance Company, according to its report, "was organized in Richmond, Va., four years ago; we have a total membership of 21,500 members. We are doing business in all the cities of this State and also in some other States. The financial condition of the company is good; it pays all claims promptly." The company occupies its own building in Richmond.

The membership of these societies is naturally much smaller than reported, but nevertheless it is large. The insurance charged is of course very high. A thousand dollar life policy costs about $250 a year premium, against $30 to $40 for a middle aged man in the

regular life insurance companies.* * Mutual Benefit Life Ins. Co.'s rate for a man of 45 is $37.42.

This high rate is to cover the weekly benefits in case of sickness, and as there is no age classification and practically no medical examination, it represents the gambler's risk. Such business, of course, opens wide the door for cheating on both sides. The educational value of conducting these enterprises is, among the Negroes, very great, and considering their lack of business training, the experiment has been quite successful. On the part of the insured, the old beneficial society was a more wholesome method of saving. The insurance society savors too much of gambling and discourages the savings bank habit.

5. Co-operative Business.

--There are undoubted proofs that the native Africans, or at least most Negro tribes, are born merchants and trafickers, and can drive good bargains even with Europeans. Little trace of this, however, survived the fire of American slavery. Communism in goods, abolition of private property, and absolute dependence on the master for daily bread almost completely robbed the slaves of all thought of economic initiative. Business enterprise would therefore be the last form of activity which we might expect to see recover from the effects of slavery, even under normal conditions. The situation to-day is, however, abnormal, from the fact that the white South is making unusual strides in commercial life, and so no sooner has the Negro learned something of the business methods about him than further advance on the part of the community has rendered them obsolete.

There are two ways in which a primitive folk may establish co-operative business effort: First, by the establishment of private business enterprise and then combining the single businesses into one joint stock company; or by beginning directly with co-operation and either developing into a less democratic form of directorship, or disintegrating into private enterprises. Negro co-operation has thus far been largely of the latter type. For instance: Opposite the campus of the Atlanta University has stood for a long time an unsightly old tumble-down dwelling. Last year a small group of Negroes bought it; they met for awhile in it; formed an organization, moved the building back and prepared to build. By regular contributions they began a fund which supported a leader with a salary. They hired laborers and masons from their own number, and with their own labor have now nearly finished a tasteful brick building. This organization was a church, but its activity has been so far co-operative business, democratic in direction and peculiarly successful. From such enterprises sprang the beneficial societies, and to-day slowly

Page 22

and with difficulty is arising real co-operative business enterprise detached from religious activity or insurance. On the other hand, private business enterprise has made some beginning, and in a few cases united into joint stock enterprises. It will be years, however, before this kind of business is very successful.

Indeed, all co-operation in business among Negroes is as yet in the experimental stage. For that reason it is especially mentioned in this study, since it represents not so much private gain as social effort for the good of the group. Of the fifteen enterprises reported in the next table, probably not more than ten are at present paying enterprises, and some of these are only moderately successful. The rest are either just making ends meet, with a prospect of future growth, or are tottering and destined to fail. The cities reporting are not in all cases identical with the nine which sent in the other reports; of those only four reported co-operative business. The reports are as follows:

Page 23

| PLACE. | NAME. | Organized. | Nature of Business. | Capital. | Members, Partn'rs or Stock holders. | Real Estate, Mortgages and Cash. | Income Last Year. | Expense. | REMARKS. | |

| 1 | Washington, D. C. | C. Savings Bank. | 1888 | Banking | $150,000 | 35 | $ 55,440 | $16,320 01 | $. | Very successful. |

| 2 | Washington, D. C. | Indus. B. & S. Co | 1886 | Building Ass'n | 50,000 | 700 | 31,000 | 396 50 | Fairly successful. | |

| 3 | Galveston, Tex | Cotton Jam'rs & Longshor. A. No. 2 | 1879 | Trades Union | 700 | cash 5,000 tools 1,000 |

6,000 00 | 2,000 00 | Very successful. | |

| 4 | Atlanta, Ga. | Atlanta L. & T. Co | 1890 | Real est. & rents | 15 | 7,000 | 700 00 | 1,000 00 | ||

| 5 | Atlanta, Ga. | Ga. Real Estate Loan & Trust Co. | 1891 | Real est. & rents | 25 | 3,500 | ||||

| 6 | Atlanta, Ga. | South View Cemetery Ass'n | 1885 | Burial Ground | 26 | 4,000 20 acres. |

Successful. | |||

| 7 | Concord, N. C. | Coleman Mfg. Co | 1897 | Mfg cotton goods | 50,000 | 100 | *20,000 | 17,000 00 | Not fully started. | |

| 8 | Richmond, Va | True Reformers' Savings Bank | 1889 | Banking and ins. | 100,000 | 500 | 115,000 | |||

| 9 | Augusta, Ga | Wk'gmen's Loan & Bldg Ass'n | 1889 | Building Ass'n | 120 | 3,400 | 3,900 00 | Very successful. | ||

| 10 | Richmond, Va | * Nickel S'v'gs Bk | Deposit and bk'g. | 30,000 | ||||||

| 11 | Birmingham, Ala. | *People's S'gs Bk | Deposit and bk'g. | 50,000 | ||||||

| 12 | Hampton, Va. | People's Bldg. & Loan Ass'n | 1889 | Building Ass'n | 75,000 | 31,000 00 | 250 homes bought | |||

| 13 | Jacksonville, Fla. | Capital Trust Co. | 1894 | Banking | 25,000 | 30 | 4,500 00 | Dividend of 10% last year. | ||

| 14 | Little Rock, Ark. | L Loan & T. Co. | 1898 | Building Ass'n | ||||||

| 15 | Hampton, Va. | Hampton Supply Co. | 1891 | Retails wood, etc | 4,500 | 12,000 00 | ||||

| 16 | Hampton, Va. | Bay Shore Hotel Co. | 1897 | Summer resort | 2,600 | 1,000 00 | ||||

| 17 | Hampton, Va. | W'k'ngmen's Cooperative Union. | 1897 | Retail store | 400 | 500 00 |

* Mill and houses are being erected; 100 acres and building

* No direct report has been received from these two banks.

Page 24

The chief co-operative businesses are those which the pressure of race prejudice rendered necessary, as, for instance, cemetery associations. Although details of only one of these is reported, there are known to be a considerable number, and they are well conducted. Efforts in handling real estate come next in popularity and have had various degrees of success. The Workingmen's Loan and Building Astocitiation, of Augusta, Ga., conconducted wholly by Negroes, is now nine years old and has been the means of securing over 100 homes for its members. Its eighth annual statement is as follows:

Eighth Annual Statement of the Workingmen's Loan and Building Association at the close of business May 31, 1898:

| RESOURCES. | |

| Loans | $15,422 66 |

| Real estate | 3,100 00 |

| Office fixtures | 75 00 |

| Cash | 49 18 |

| $18,646 84 |

| LIABILITIES. | |

| Capital stock | $10,725 00 |

| Bills payable | 1,540 38 |

| Undivided profits | 3,324 03 |

| Surplus | 3,057 43 |

| $18,646 84 |

The building and loan association of Washington has been pretty successful. It was organized for the "purpose of demonstrating business capacity and unity in the Negro race, and was intended especially to operate among, and to secure the support of the large class of colored people employed in the departmental service of the government here and as school teachers in this city, since this class was known to handle, in the aggregate, large sums of money monthly. But our hopes in this direction have not been realized. Such success as our company has achieved came almost altogether from the wage-earning element, not from the salary drawers. These latter have seemed to prefer to put their money as well as their personal influence on the side of business institutions conducted by white persons, institutions in which they are rigidly excluded from all participation whatever. And a still more discouraging aspect of the situation is that there seems to be but little change for the better in this condition. Not alone in this association is this sentiment observable among the better paid element of the race, but it applies to all organized business efforts in this city so far as I am aware. These are supported by the middle and lower classes, among whom the instinct of race affinity is strongest and the support of race institutions the most permanent and substantial."*

*Report of Secretary, Mr. Henry E. Baker.

Page 25

In Little Rock, Ark., several well-to-do Negroes have started a building association, with a nickel savings department attached. The company was incorporated in 1898, and is now ready for work.

The People's Building and Loan Association of Hampton, Va., has been very successful. It has been in operation nine years and has a paid up capital of $75,000. Last year (1897) it did a business of $31,000, on which the gross profits were $5,000. The officers have been, and still are, all colored. The association has been the means of erecting 250 homes. It "has proven a blessing to the poor people of this community by assisting them to get homes; also a good investment for those who desired to bank a small amount, it having paid these years 7 and 8% interest." It has two salaried officials and 500 members.*

*Report of a stockholder.

Hampton also has two successful co-operative stores--a form of enterprise which has not heretofore succeeded. The Hampton Supply Company was organized in the year 1891 and has 100 members. The paid up capital is $45,000. It went into business in 1896, and since that time it has dealt in wood, coal and feed stuff, and does a businees of $12,000 per year. It gives employment to five persons.

The Workingmen's Co-operative Union has twenty members, a capital of $400 and does a business of $500 to $1,000 annually. It handles coal, wood, feed and groceries.

In this connectien the Bay Shore Hotel Company of Hampton may be noticed. It is an attempt to furnish a decent summer resort for Negroes, since the majority of resorts are shut against them. It was organized in 1897, with sixty members and a paid up capital of $2,600. Last season it did a business of $1,000, employing four persons.

Of these three enterprises in Hampton, an officer of Hampton Institute writes:

"These are all incorporated companies, officered and controlled by colored men. They have been organized and operated as an outgrowth directly of the demands of the people rather than as a speculative investment in the different forms of business in rivalry of those already in existence; and to this extent they have all been successful."*

*Mr. D. R. Lewis, instructor in mechanical drawing.

The most successful Negro bank of the six or seven which have been organized by Negroes, is the Capital Savings bank of Washington, now ten years old.* *NOTE.--It was reported in the last Hampton Conference that there were over fifty Negroes in Washington worth $10,000 and over. Returns from thirty-five of these showed that only twelve invested their money in Negro business enterprises, and only seven of these invested to any considerable extent. This, after all, is but natural. The money of men who have successfully accumulated property is attracted mainly by the returns to be gained and less by philanthropic or sentimental reasons; that of the lower and middle classes is more influenced by considerations of race pride and social advance. It is, however, no mean compliment to Negro business enterprise that it has thus early been able to attract 20% of the well-to-do of the race in competition with the business of an industrial age.

When it started, white business men of Washington refused to rent it proper quarters, whereupon it bought a pleasant building

Page 26

on F street, where it conducts a growing business. Other banks, like the one in Baltimore, have failed through the rascality of some of the officers.

A very promising institution is the Capital Trust Company of Jacksonville, Fla., organized March 6, 1894. It consists of thirty Negro business men and artisans who have invested $25,000 in a banking business. They loan money and discount paper. They have no salaried officials and reduce expenses to a minimum ($6.35 for last year). The officials manage the affairs of the bank in connection with their own business. Last year they earned 18% on their capital and distributed 10% in dividends. The president is a contractor and builder.

The banking business conducted by the Grand Fountain of the Order of True Reformers, on North Second street, Richmond, Va., is capitalized at $100,000. It owns much property, over $115,000 in buildings, residences and the like. There are 7,086 depositors reported, and $101,933.32 deposited. Since its establishment in 1889 it claims to have handled $3,795,667.36, and to have paid out for the insurance department of the order $370,910.75. The work at present is reported as being "in a prosperous condition," and it is certainly the largest financial enterprise conducted by Negroes outside the church organizations.

No direct reports have been received from the other banks, but they are known to exist. The Atlanta Loan and Trust Company, which has invested chiefly in city lots, "has not improved in the last two years. The company is self-sustaining, but yields no dividends to the stockholders." This is probably the condition of several other ventures.

Two notable enterprises must be mentioned. One is the Cotton Jammers and Longshoremen's Association No. 2 of Galveston, Tex., who "have the reputation of doing the best work of any cotton screwmen at this port." They are more than a trade's union, as they have invested in $1,000 worth of tools used in the business. They receive dues from members and also from the different gangs at work. They pay sick and death benefits. The association is nineteen years old. The other enterprise is the Coleman Manufacturing Company, which is erecting a cotton mill at Concord, N. C. The president and all except one of the directors are Negroes, and in August, 1897, they issued the following prospectus:

COLEMAN MANUFACTURING COMPANY.

"Incorporated under the laws of the State of North Carolina. Capital stock, $50,000.

"Concord, N. C., August 20, 1897.

"DEAR SIR: We beg to call your attention to our new enterprise, indicated above. We are a co-operative stock company of colored men who propose to build and operate a cotton mill in the interest of the race. This is a gigantic effort and we need the cooperation of every friend of the race. Its promoters are among the most successful Negro business men in the country. Many of its stockholders are influential citizens of the white race, and may be found in every section of the country. Capital stock has been raised to $100,000, half of which is already subscribed; the remainder we now offer at $100 per share. This may be paid in installments of 10% or taken in paid up stock. When the full amount has been paid, certificates

Page 27

of stock, negotiable, are given. From 40,000 to 50,000 bricks are being turned out daily; we expect to begin laying them in a few weeks time. When completed we will employ from 300 to 400 hands. Avenues along all lines of work will open up, and we want some one to open a boarding house, run a truck farm, livery stable, dairy, etc. We urge you to consider this Negro enterprise and write us for any further information you may desire. Yours in interest of the race,

"W. C. COLEMAN."

Since that time the mill and some houses have been built, and "we are ready to install engine and boiler and other machinery. Work of operation will commence as soon as we sell some more stock." A special trade edition of the Concord Times, a white paper, March 10, 1898, speaks of the enterprise as follows:

"Can the Negro race successfully own and operate cotton mills? This question so long in doubt is about to be answered and we believe in the affirmative. The first great stride in that direction was taken when on the 8th of February, 1898, was laid with Masonic honors the corner stone of the handsome three-story brick building, 80×120 feet in dimensions, of the Coleman Cotton Mill. It was indeed a marked epoch in the history of the Negro race and pronounced by all present an entire success. Noted speakers from all over the United States were invited and the railroads gave reduced rates from all points. Following the laying of the corner stone was the annual election of officers, who are as follows: R. B. Fitzgerald, of Durham, N. C., president; E. A. Johnson, of Raleigh, N. C., vice-president, and W. C. Coleman, of Concord, N. C., secretary and treasurer. The following gentlemen constitute the board of directors: Rev. S. C. Thompson, Camden, S. C.; L. P. Berry, Statesville, N. C.; John C. Dancy, Salisbury, N. C.; Prof. S. B. Pride, Charlotte, N. C.; Prof. C. F. Meserve, Raleigh, N. C., and Robert McRae, Concord, N. C. Among these are some of the highest lights of the Negro race, and under their careful direction we have no doubts as to the final results of the enterprise. The promoter of this enterprise, Mr. W. C. Coleman, is the wealthiest Negro in the State, and he has rallied around him not only the leaders of his race but has the endorsement of many of the most successful financiers among our white citizens throughout the State. The mill is to have from 7,000 to 10,000 spindles and from 100 to 250 looms, and, by their charter, will be allowed to spin, weave, manufacture, finish and sell warps, yarns, cloth, prints or other fabrics made of cotton, wool or other material. They own at present, in connection with the plant, about 100 acres of land on the main line of the Southern Railway and near the site of the mill. The mill and machinery with all the fixtures complete will represent an outlay of nearly $66,000, and will give employment to a number of hands. The building is now completed and ready for machinery.

"Let us add that Concord has reason to and does feel proud of the fact that she has the only cotton mill in the world owned, conducted and operated by the Negro race."

This experiment will certainly be watched with interest all over the land.

7. Benevolence.

In an advanced civilization a study of efforts for social

Page 28

betterment would confine itself chiefly to the work of special benevolent agencies which had reform and rescue work as their immediate objects. Institutions and organizations for the accomplishment of these ends have, in most modern countries, been developed after long trial and experiment. The culture of the mass of the race we are studying, however, has not yet come to the point of differentiating special organs of benevolence and reform to any great extent. Consequently this study has to review chiefly the activities of organizations whose main object is not benevolent but who incidentally do much work to promote the social wellfare. Even here, as mentioned before, we can by no means gather up all efforts because so many are unsystemaaic and unorganized.

Especially in the matter of purely benevolent work do we find lack of organization and system. Probably no portion of the people of the country more quickly respond to charitable appeals of all sorts than do the colored people. They have few charitable societies but they give much money, work and time to charitable deeds among their fellows; they have few orphan asylums, but a large number of children are adopted by private families, often when the adopting family can ill afford it; there are not many old folk's homes, but many old people find shelter and support among families to whom they are not related. In fine, the open hospitality of a primitive people is especially noticeable among Negroes.

We, however, are to notice only the cases where the sense of the importance of such relief work has so impressed itself upon the group as to lead to systematic cooperation in performing it. Returns from all such enterprises, even in the limited territory studied, have not been obtained, but a table of twenty-one organizations which seems fairly representative, follows. Here, again, the limits of the nine cities have not been adhered to. Only seven of the efforts reported were from those cities. (For table see pages 30-31.)

Some of these enterprises deserve particular attention. The missionary corps of Fort Smith, Ark., writes: "The object of the corps is not only charitable, but to advance the race religiously, morally and intellectually. We have organized a Mother's Meeting and Sewing School."

There are three orphan asylums reported, and several others are known to exist. An account of the Carrie Steele Orphanage is printed among the following papers. The Tennessee Orphanage and Industrial school is an interesting offshoot of the Negro Department of the Tennessee Centennial. The head of that department, who is now principal of the orphanage, says:

"At the beginning of the work of the Negro Department of the Tennessee Centennial it was remarked that something should be done that would be a lasting benefit to our people. It was suggested to take advantage of the enthusiasm connected with that organization and create a home for some of the many parentless and neglected boys and girls of our race, take them off the streets and train not only their heads but hearts and hands as well, that they may become useful men and women.

"As a start towards raising money for this purpose the Orphans' Home buttons were placed on sale and hundreds of them sold.

"Next, the 'Symposium,' a 5 and 10 cent entertainment, was given at the Spruce Street Baptist Church, by which about $100 was made. Several

Page 29

small sums of money were donated by Sunday-schools and individuals. Then came the 'field day' at Cumberland Park, in the summer of 1896."

At a meeting of Negroes to establish this asylum, the Nashville American, March 14, 1898, reports a colored clergyman as saying:

"When we think of the army of boys and girls growing up in our city, in ignorance, vice and shame, without any care and protection, we are appalled. These fill the work house, the chain gang, the haunts of 'Magdalene' and the penitentiary. In Nashville we have a Negro orphaned and neglected population of not less than 2,000 children. Think of it, 2,000 Negro children in our midst parentless and neglected.

"I submit, my friends, it is an unwelcome thought, but nevertheless, this army of children is growing up without Christian influence, scarcely any moral teaching, and without education to fit them for life's duties. What does this orphanage movement mean? you ask. It means an effort to save at least a few of these unfortunate little ones from abject poverty and possibly a life of shame and ultimate ruin. It means an effort at their education, their moral and Christian development, and fitting them to be intelligent, honorable citizens. It has behind it the spirit of the highest and best humanity, and our duty toward it as citizens is first to give it our moral support.