A School History of the Negro Race in America, from 1619 to 1890,

With a Short Introduction as to the Origin of the Race; Also a Short Sketch of Liberia:

Electronic Edition.

Johnson, Edward A. (Edward Austin), 1860-1944

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Andrew Leiter

Images scanned by

Andrew Leiter

Text encoded by

Fiona Mills and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 250K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) A School History of the Negro Race in America, from 1619 to 1890, With a Short Introduction as to the Origin of the Race; Also a Short Sketch of Liberia.

(spine) School History of the Negro Race in America

Edward A. Johnson, L. B.

First Edition

194 p., ill.

Raleigh

Edwards & Broughton, Printers and Binders.

1890

Call Number C326 J67 c. 4 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- History.

- African Americans -- Social conditions.

- African American soldiers.

- Slavery -- United States -- History.

Revision History:

- 2001-07-20,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-07-25,

Jill Kuhn, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-07-15,

Fiona Mills

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-06-09,

Andrew Leiter

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

A SCHOOL HISTORY

OF THE

NEGRO RACE IN AMERICA,

FROM 1619 TO 1890,

WITH A SHORT INTRODUCTION

AS TO

THE ORIGIN OF THE RACE;

ALSO A

SHORT SKETCH OF LIBERIA.

BY

EDWARD A. JOHNSON, L. B.,

Principal of the Washington School,

RALEIGH, N. C.

FIRST EDITION.

1890.

RALEIGH:

EDWARDS & BROUGHTON, PRINTERS AND BINDERS.

1890.

Page 2

[Entered According to Act of Congress, in the Year 1890,

BY E. A. JOHNSON,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.]

Page 3

PREFACE.

To the many thousand colored teachers in our country is this book dedicated. During my experience of eleven years as a teacher, I have often felt that the children of the race ought to study some work that would give them a little information on the many brave deeds and noble characters of their own race. I have often observed the sin of omission and commission on the part of white authors, most of whom seem to have written exclusively for white children, and studiously left out the many creditable deeds of the Negro. The general tone of most of the histories taught in our schools has been that of the inferiority of the Negro, whether actually said in so many words, or left to be implied from the highest laudation of the deeds of one race to the complete exclusion of those of the other. It must, indeed, be a stimulus to any people to be able to refer to their ancestors as distinguished in deeds of valor, and peculiarly so to the colored people. But how must the little colored child feel when he has completed the assigned course of U. S. History and in it found not one word of credit, not one word of favorable comment for even one among the millions of his foreparents who have lived through

Page 4

nearly three centuries of his country's history! The Negro is hardly given a passing notice in many of the histories taught in the schools; he is credited with no heritage of valor; he is mentioned only as a slave, while true historical records prove him to have been among the most patriotic of patriots, among the bravest of soldiers, and constantly a God-fearing, faithful producer of the nation's wealth. Though a slave to this government, his was the first blood shed in its defense in those days when a foreign foe threatened its destruction. In each of the American wars the Negro was faithful -- yes, faithful to a land not his own in point of rights and freedom, but, indeed, a land that, after he had shouldered his musket to defend, rewarded him with a renewed term of slavery. Patriotism and valor under such circumstances possess a peculiar merit and beauty. But such is the truth of history; and may I not hope that the study of this little work by the boys and girls of the race will inspire in them a new self-respect and confidence. Much, of course, will depend on you, dear teachers, into whose hands I hope to place this book. By your efforts and those of the children, you are to teach, from the truth of history, that complexions do not govern patriotism, valor and sterling integrity.

My endeavor has been to shorten this work as

Page 5

much as I thought consistent with clearness. Personal opinions and comments have been kept out. A fair, impartial statement has been my aim. Facts are what I have tried to give without bias or prejudice, and may not something herein said hasten on that day when the race for which these facts are written, following the example of the noble men and women who have gone before, level themselves up to the highest pinnacle of all that is noble in human nature.

I respectfully request that my fellow-teachers will see to it that the word Negro is written with a capital N. It deserves to be so enlarged and will help, perhaps, to magnify the race it stands for in the minds of those who see it.

E. A. J.

Page [6a]

INDEX.

- I. Introduction . . . . . 7

- II. Beginning of Slavery in the Colonies, . . . . . 14

- III. The New York Colony . . . . . 20

- IV. Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut . . . . . 22

- V. New Hampshire and Maryland . . . . . 31

- VI. Delaware and Pennsylvania . . . . . 37

- VII. North Carolina . . . . . 38

- VIII. South Carolina . . . . . 41

- IX. Georgia . . . . . 43

- X. Habits and Customs of the Southern Colonies . . . . . 49

- XI. Negro Soldiers in Revolutionary Times . . . . . 52

- XII. Negro Heroes of the Revolution . . . . . 60

- XIII. The War of 1812 . . . . . 71

- XIV. Efforts for Freedom . . . . . 77

- XV. Liberia . . . . . 81

- XVI. Frederick Douglass . . . . . 83

- XVII. Nat. Turner and Others Who Struck for Freedom . . . . . 87

- XVIII. Anti-Slavery Agitation . . . . . 95

- XIX. Examples of Underground Railroad Work . . . . . 98

Page [6b] - XX. Slave Population of 1860 . . . . . 99

- XXI. The War of the Rebellion . . . . . 100

- XXII. Employment of Negro Soldiers . . . . . 106

- XXIII. Fort Pillow . . . . . 116

- XXIV. Around Petersburg . . . . . 120

- XXV. The Crater . . . . . 124

- XXVI. Incidents of the War . . . . . 129

- XXVII The End of the War . . . . . 133

- XXVIII. Reconstruction -- 1865-'68 . . . . . 136

- XXIX. Progress Since Freedom . . . . . 140

- XXX. Religious Progress . . . . . 144

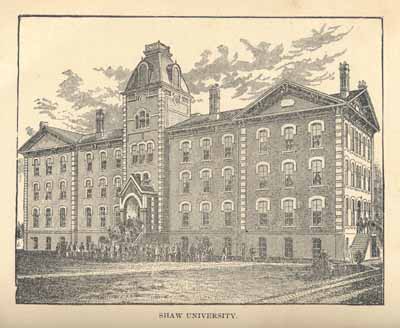

- XXXI. Educational Progress . . . . . 153

- XXXII. Financial Progress . . . . . 160

- XXXIII. Some Noted Negroes . . . . . 165

- XXXIV. Free People of Color in North Carolina . . . . . 186

- XXXV. Conclusion . . . . . 192

CHAPTER. . . . . . PAGE.

Page 7

A SCHOOL HISTORY

OF THE

NEGRO RACE IN AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION.

The Origin of the Negro is definitely known. Some very wise men, writing to suit prejudiced readers, have endeavored to assign the race to a separate creation and deny its kindred with Adam and Eve. But historical records prove the Negro as ancient as the most ancient races -- for 5,000 years into the dim past mention is made of the Negro race. The Pyramids of Egypt, the great temples on the Nile, were either built by Negroes or people closely related to them. All the science and learning of ancient Greece and Rome was once in the hands of the foreparents of the American slaves. They are, then, descendants of a race of people once the most powerful on earth, the race of the Pharaohs. History, traced from the flood, makes the three sons of Noah, Ham, Shem and Japheth, the progenitors of the three primitive races of the earth -- the Mongolian, descended from Shem and settled in Southern

Page 8

and Eastern Asia; the Caucasian, descended from Japheth and settled in Europe; the Ethiopian, descended from Ham and settled in Africa and adjacent countries. From Ham undoubtedly sprung the Egyptians who, in honor of Ham, their great head, named their principal god Hammon or Ammon.

Ham was the father of Canaan, from whom descended the powerful Canaanites so troublesome to the Jews. Cush, the oldest son of Ham, was the father of Nimrod, "the mighty one in the earth" and founder of the Babylonian Empire. Nimrod's son built the unrivalled City of Nineveh in the picturesque valley of the Tigress. Unless the Bible statement be false that "God created of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on the face of the earth," and the best historians have erred, then the origin of the Negro is high enough to merit his proudest boasts of the past, and arouse his grandest hopes for the future.

The Present Condition of the African is the result of the fall of the Egyptian empire, which was in accord with the Bible prophecy of all nations who forgot God and worshipped idols. That the Africans, were once a great people is shown by their natural love for the fine arts. They are poetic by nature, and national airs sung long ago by exploring parties in Central Africa are still held by them,

Page 9

and strike the ears of more modern travellers with joy and surprise.

Ancient Cities Discovered in the very heart of Africa, having well laid off streets, improved wharfs, and conveniences for trade, connect these people with a better condition in the past than now. While many of the native Africans are desperately savage, yet in their poor, degraded condition it is the unanimous testimony of missionaries and explorers that many of these people have good judgment, some tribes have written languages, and show skill in weaving cloth, smelting and refining gold and iron and making implements of war.

Their Wonderful regard for truth and virtue is surprising, and fixes a great gulf between them and other savage peoples. They learn rapidly, and, unfortunately, it is too often the case that evil teaching is given them by the vile traders who frequent their country with an abundance of rum, mouths full of curses, and the worst of bad English.

Long Years Spent in the most debilitating climate on earth and violation of divine law, made the African what he was when the slave trade commenced in the 16th century. But his condition was not so bad that he could not be made a good citizen. Nay, he was superior to the ancient savage Briton whom Cæsar found in England and described as unfitted

Page 10

to make respectable slaves of in the Roman Empire. The Briton has had eighteen centuries to be what he is, the Negro has had really but twenty-five years. Let us weigh his progress in just balances.

SOME QUOTATIONS FROM LEADING WRITERS ON THE NEGRO.

"The Sphinx may have been the shrine of the Negro population of Egypt, who, as a people, were unquestionably under our average size. Three million Buddhists in Asia represent their chief deity, Buddha, with Negro features and hair. There are two other images of Buddha, one at Ceylon and the other at Calanse, of which Lieutenant Mahoney says: 'Both these statues agree in having crisped hair and long, pendant earrings.'" -- Morton

"The African is a man with every attribute of humankind. Centuries of barbarism have had the same hurtful effects on Africans as Pritchard describes them to have had on certain of the Irish who were driven, some generations back, to the hills in Ulster and Connaught" -- the moral and physical effect are the same.

"Ethnologists reckon the African as by no means the lowest of the human family. He is nearly as

Page 11

strong physically as the European; and, as a race, is wonderfully persistent among the nations of the earth. Neither the diseases nor the ardent spirits which proved so fatal to the North American Indians, the South Sea Islanders and Australians, seem capable of annihilating the Negroes. They are gifted with physical strength capable of withstanding the severest privations. Many would pine away in a state of slavery. No Krooman can be converted into a slave, and yet he is an inhabitant of the low, unhealthy west coast; nor can any of the Zulu or Kaffir tribe be reduced to bondage, though all these live in comparatively elevated regions. We have heard it stated by men familiar with some of the Kaffirs, that a blow given, even in play by a European, must be returned. A love of liberty is observable in all who have the Zulu blood, as the Makololo, the Watuta. But blood does not explain the fact. A beautiful Barotse Woman at Naliele, on refusing to marry a man whom she did not like, was in a pet given by the headman to some Mambari slave traders from Benguela. Seeing her fate, she seized one of their spears, and, stabbing herself, fell dead." -- Livingstone's Works.

"In ancient times the blacks were known to be so gentle to strangers that many believed that the

Page 12

gods sprang from them. Homer sings of the ocean, father of the gods; and says that when Jupiter wishes to take a holiday, he visits the sea, and goes to the banquets of the blacks, -- a people humble, courteous and devout."

THE CURSE OF NOAH WAS NOT DIVINE!

The following passage of scripture has been much quoted as an argument to prove the inferiority of the Negro race. The Devil can quote scripture but not always correctly: "And Noah began to be an husbandman and he planted a vineyard: and he drank of the wine, and was drunken and was uncovered in his tent, and Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without, and Shem and Japheth took a garment and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father's nakedness, and Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him, and he said, cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said: Blessed be the Lord God of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant. God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant."

After the flood Noah's mission as a preacher to the people was over. He so recognized it himself, and settled himself down with his family on a vineyard. He got drunk of the wine he made and disgracefully lay in nakedness; on awaking from his drunken stupor and learning of Ham's acts, he in rage speaks his feelings to Canaan, Ham's son. He was in bad temper at this time, and spoke as one in such a temper in those times naturally would speak. To say he was uttering God's will would be a monstrosity -- would be to drag the sacred words of prophecy through profane lips, and make God speak His will to men out of the mouth of a drunkard, of whom the holy writ says none can enter the kingdom. A drunken prophet strikes the mind with ridicule! Yet, such was Noah, if at all -- and such the character of that prophet, whom biased minds have chosen as the expounder of a curse on the Negro race. It is not strange that so few people have championed the curse theory of the race, when we think that in so doing they must at the same time endorse Noah's drunkenness.

But, aside from this, the so-called prophecy of Noah has not become true. The best evidence of a prophecy is its fulfillment. Canaan's descendants have often conquered, though Noah said they would not. Goodrich makes the Canaanites, so powerful in the fortified cities of Ai and Jericho, the direct descendants of Canaan. They were among the most powerful people of olden times. They and their kindred built up Egypt, Phoenicia, the mother of the alphabet, and Nineveh and Babylon the two most wonderful of ancient cities. The Jews, God's chosen people, were enslaved by the kindred of Canaan both in Egypt and Babylon. Melchizedek

Page 13

(King of Righteousness), a sacred character of the old Testament, was a Canaanite. So, rather than being a race of slaves as Noah predicted, the Canaanitish people have been the greatest people of the earth. The great nations of antiquity were in and around Eastern Africa and Western Asia in which is located Mt. Ararat supposed to be the spot on which the ark rested after the flood. These nations sprang from the four sons of Ham -- Cush, Mizarim, Phut and Canaan. The Cushites were Ethiopians who lived in Abyssinia. The Mizarimites were Egyptians who lived in Egypt and so distinguished for greatness. The Canaanites occupied the country including Tyre and Sidon and stretching down into Arabia as far as Gaza and including the province of the renowned Queen of Sheba.

In the light of true history the curse theory of the Negro melts like snow under a summer sun. We contend from the above facts that Noah did not utter a prophecy when he spoke to Canaan, and as proof of that fact we have quoted a few historical facts to show that if he did make such a prophecy it was not fulfilled. We will add further, that the part of the alleged prophecy conferring blessings on Shem and Japheth has also fallen without verification, in that the descendants of these two personages have more than once been enslaved.

It seems hardly necessary in this age of enlightenment to refer to the Curse Theory argued so persistently by those who needed some such argument as an apology for wrong doing, but still there are some who still believe in it, having never cut loose from the moorings of blind prejudice. The Color Theory was also quite popular formerly as an argument in support of the curse of Noah. We hold that the color of the race is due to climatic influences, and in support of this view read this quotation in reference to Africa: "As we go westward we observe the light color predominating over the dark; and then, again, when we come within the influence of the damp from the sea air, we find the shade deepened into the general blackness of the coast population."

"It is well known that the Biseagan women are shining white, the inhabitants of Granada, on the contrary, dark, to such an extent that in this region (West Europe), the pictures of the blessed Virgin and other saints are painted of the same color."

Black is no mark of reproach to people who do not worship white. The West Indians in the interior represent the devil as white. The American Indians make fun of the "pale face" and so does the native African. People in this country have been educated to believe in white because all that is good has been ascribed to the white race both in pictures and words. God, the angels and all the prophets are pictured white and the Devil is represented as black.

Page 14

CHAPTER II.

THE BEGINNING OF SLAVERY IN THE

COLONIES.

The first Negroes landed at Jamestown, Va. In the year 1619, a Dutch trading vessel being in need of supplies weighed anchor at Jamestown, and exchanged fourteen Negroes for food and supplies. The Jamestown people made slaves of these fourteen Negroes, but did not pass any law to that effect until the year 1662, when the number of slaves in the colony was then nearly 2,000, most of whom had been imported from Africa.

How they were Employed. The Jamestown colony early discovered the profits of the tobacco crop, and the Negro slaves were largely employed in this industry where they proved very profitable, They were also enlisted in the militia, but could not bear arms except in defense of the colonists against the Indians. The greater part of the manual labor of all kinds was performed by the slaves.

The Slaves Imported came chiefly from the west coast of Africa. They were crowded into the holds of ships in droves, and often suffered for food and

Page 15

drink. Many, when opportunity permitted, would jump overboard rather than be taken from their homes. Various schemes were resorted to by the slave-traders to get possession of the Africans. They bought many who had been taken prisoners by stronger tribes than their own; they stole others, and some they took at the gun and pistol's mouth.

Many of the Captives of the slave-traders sold in this country were from tribes possessing more or less knowledge of the use of tools. Some came from tribes skilled in making gold and ivory ornaments, cloth, and magnificent steel weapons of war. The men had been trained to truthfulness, honesty, and valor, while the women were virtuous even unto death. While polygamy is prevalent among most African tribes, yet their system of marrying off the young girls at an early age, and thus putting them under the guardianship of their husbands, is a protection to them; and the result is plainly seen by travellers who testify positively to the uprightness of the women.

The Ancestors of the American Negroes, though savage in some respects, yet were not so bad as many people think. The native African had then, and he has now, much respect for what we call law and justice. This fact is substantiated by the

Page 16

numerous large tribes existing, individuals of which grow to be very old, a thing that could not happen were there the wholesale brutalism which we are sometimes told exists. All native Africans universally despise slavery, and even in Liberia, have a contempt for the colored people there who were once slaves in America.

The Jamestown Slaves were doomed to servitude and ignorance both by law and custom; they were not allowed to vote, and could not be set free even by their masters, except for "some meritorious service." Their religious instruction was of an inferior order, and slaves were sometimes given to the white ministers as pay for their services.

The Free Negroes of Jamestown were in a similar condition to that of the slaves. They could vote and bear arms in defence of the colony, but not for themselves. They were taxed to bear the expenses of the government, but could not be educated in the schools they helped to build. Some of them managed to acquire some education and property.

The Negro Heroes who may have exhibited their heroism in many a daring feat during the early history of Jamestown are not known. It is unfortunate that there was no record kept except that of the crimes of his ancestors in this country. Judging,

Page 17

however, from the records of later years, we may conclude that the Negro slave of Jamestown was not without his Banneka or Blind Tom. Certainly his labor was profitable and may be said to have built up the colony.

When John Smith became Governor of the Jamestown colony, there were none but white inhabitants; their indolent habits caused him to make a law declaring that "he who would not work should not eat." Prior to this time the colony had proved a failure and continued so till the introduction of the slaves, under whose labor it soon grew prosperous and recovered from its hardships.

Thomas Fuller, sometimes called "the Virginia Calculator," must not be overlooked in speaking of the record of the Virginia Negro. He was stolen from his home in Africa and sold to a planter near Alexandria, Va. His genius for mathematics won for him a great reputation. He attracted the attention of such men as Dr. Benjamin Rush, of Philadelphia, who, in company with others, was passing through Virginia. Tom was sent for by one of the company and asked, "how many seconds a man of seventy years, some odd months, weeks and days, had lived?" "He gave the exact number in a minute and a half." The gentleman who questioned him took his pen, and after some figuring

Page 18

told him he must be mistaken, as the number was too great. "Top, massa!" cried Tom, you hab left out the leap year" -- and sure enough Tom was correct. -- Williams.

The following was published in several newspapers when Thomas Fuller died:

"DIED. -- Negro Tom, the famous African Calculator, aged 80 years. He was the property of Mrs. Elizabeth Cox, of Alexandria. Tom was a very black man. He was brought to this country at the age of fourteen, and was sold as a slave with many of his unfortunate countrymen. This man was a prodigy; though he could neither read nor write, he had perfectly acquired the use of enumeration. He could give the number of months, days, weeks, hours, minutes and seconds for any period of time that a person chose to mention, allowing in his calculations for all the leap years that happened in the time. He would give the number of poles, yards, feet, inches and barleycorns in a given distance -- say the diameter of the earth's orbit -- and in every calculation he would produce the true answer in less time than ninety-nine out of a hundred men would take with their pens. And what was, perhaps, more extraordinary, though interrupted in the progress of his calculations and engaged in discourse upon any other subject, his operations were

Page 19

not thereby in the least deranged. He would go on where he left off, and could give any and all of the stages through which his calculations had passed. Thus died Negro Tom, this untaught arithmetician, this untutored scholar. Had his opportunities of improvement been equal to those of a thousand of his fellow men, neither the Royal Society of London, the Academy of Sciences at Paris, nor even a Newton himself need have been ashamed to acknowledge him a brother in science."

How many of his kind might there have been had the people of Jamestown seen fit to give the Negroes who came to their shores a laborer's and emigrant's chance, rather than enslaving them! Much bloodshed and dissension might thus have been avoided, and the honor of the nation never besmirched with human bondage.

Page 20

CHAPTER III.

THE NEW YORK COLONY.

The enslavement of the Negro seems to have commenced in the New York Colony about the same time as at Jamestown. The slaves were used on the farms and became so profitable that about the time the English took the colony from the Dutch, 1664, there was a great demand for slaves, and the trade grew accordingly.

The Privileges of the Slaves in New York were for a while a little better than in Virginia. They were taken into the church and baptized, and no law was passed to prevent their getting an education. But the famous Wall Street, now the financial center of the New World, was once the scene of an auction block where Indians and persons of Negro descent were bought and sold. A whipping boss was once a characteristic office in New York City.

The Riot of 1712 shows the feeling between the master and servant at that time. The Negro population being excluded from schools, not allowed to own land even when free, and forbidden to "strike a Christian or Jew" in self-defence, and their testimony

Page 21

excluded from the courts, arose in arms and with the torch; houses were burned and many whites killed before the militia suppressed them. Many of the Negroes of New York were free, and many came from the Spanish provinces.

Page 22

CHAPTER IV.

MASSACHUSETTS, RHODE ISLAND AND

CONNECTICUT.

Negro slavery existed in Massachusetts as early as 1633. The Puritan fathers who came to this country in search of liberty did not hesitate to carry on for more than a century a disgraceful traffic in human flesh and blood. The New England ships of the 17th century brought cargoes of Negroes from the west coast of Africa and the Barbadoes. They sold many of them in New England as well as in the Southern colonies. In 1764 there were nearly 6,000 slaves in Massachusetts, about 4,000 in Rhode Island and the same in Connecticut.

The Treatmentof the slaves in these colonies at this time was regulated by laws which classed them as property, "being rated as horses and hogs." They could not bear arms nor be admitted to the schools. They were baptized in the churches, but this did not make them freemen, as it did white serfs.

Better Treatment was given the slaves as the colonies grew older and were threatened with wars. It was thought that the slaves might espouse the

Page 23

cause of the enemy, and for this reason some leniency was shown them.

Judge Samuel Sewall, a Chief Justice of Massachusetts wrote a tract in 1700 warning the people of New England against slavery and ill treatment of Negroes. He said: "Forasmuch as Liberty is in real value next unto Life, none ought to part with it themselves, or deprive others of it, but upon most mature consideration."

Judge Sewall's tract greatly excited the New England people on the subject of emancipating their slaves. "The pulpit and the press were not silent, and sermons and essays in behalf of the enslaved Africans were continually making their appearance."

The Slaves Themselves aroused by these favorable utterances from friendly people made up petitions which they presented with strong arguments for their emancipation. A great many slaves brought suits against their masters for restraining them of their liberty. In 1774 a slave "of one Caleb Dodge," of Essex county, brought suit against his master praying for his liberty. The jury decided that there was "no law in the Province to hold a man to serve for life," and the slave of Caleb Dodge won the suit.

Felix Holbrook and other slaves presented a petition

Page 24

to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1773, asking to be set free and granted some unimproved lands where they might earn an honest living as freemen. Their petition was delayed consideration one year, and finally passed. But the English governors, Hutchinson and Gage, refused to sign it, because they perhaps thought it would "choke the channel of a commerce in human souls."

British Hatred to Negro freedom thus made itself plain to the New England slaves, and a few years later, when England fired her guns to subdue the revolution begun at Lexington, the slave population enlisted largely in the defence of the colonists. And thus the Negro slave by valor, patriotism and industry, began to loosen the chains of his own bondage in the Northern colonies.

PHILLIS WHEATLEY.

Before passing from the New England colonies it would be unfortunate to the readers of this book were they not made acquainted with the great and wonderful career of the young Negro slave who bore the above name. She came from Africa and was sold in a Boston slave market in the year 1761 to a kind lady who was a Mrs. Wheatley. As she

Page 25

sat with a crowd of slaves in the market, naked, save a piece of cloth tied about the loins, her modest, intelligent bearing so attracted Mrs. Wheatley that she selected her in preference to all the others. Her selection proved a good one, for, with clean clothing and careful attention, Phillis soon began to show a great desire for learning. Though only eight years old, this young African, whose race all the learned men said were incapable of culture, within little over a year's time so mastered the English language as to be able to read the most difficult parts of the Bible intelligently. Her achievements in two or three years drew the leading lights of Boston to Mrs. Wheatley's house, and with them she talked and carried on correspondence concerning the popular topics of the day. Everybody either knew or knew of Phillis. She became skilled in Latin and translated one of Ovid's stories, which was published largely in English magazines. She published many poems in English, one of which was addressed to General George Washington. He sent her the following letter in reply, which shows that Washington was as great in heart as in war:

"CAMBRIDGE, 28th February, 1776.

"Miss Phillis:

-- Your favor of the 26th of October did not reach my hands till the middle of

Page 26

December. * * * * I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me in the elegant lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyric, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your poetical talents, in honor of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the poem, had I not been apprehensive that, while I only meant to give the world this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public prints.

"If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near headquarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses, and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am with great respect,

"Your humble servant,

"GEORGE WASHINGTON."

-- Williams.

Phillis was emancipated at the age of twenty-one. Soon after that her health failed and she was sent to Europe, where she created even a greater sensation than in America. Men and women in the very highest stations of the Old World were wonder-struck, and industriously attentive to this humble

Page 27

born African girl. While Phillis was away Mrs. Wheatley became seriously ill and her daily longings were to see "her Phillis," to whom she was so much devoted. It is related that she would often turn on her sick-couch and exclaim, "See! Look at my Phillis! Does, she not seem as though she would speak to me?" Phillis was sent for to come, and in response to the multitude of kindnesses done her by Mrs. Wheatley, she hastened to her bed-side where she arrived just before Mrs. Wheatley died, and "shortly had time to close her sightless eyes."

Mr. Wheatley after the death of his wife, married again and settled in England. Phillis being thus left alone also married. Her husband was named Peters. He, far inferior to her in most every way and becoming jealous of the favors shown her by the best of society, became very cruel. Phillis did not long survive his harsh treatment, and she died "greatly beloved" and mourned on two continents on December 5th, 1784, at the age of 31.

Thus passed away one of the brightest of the race, whose life was as pure as a crystal and devoted to the most beautiful in poetry, letters and religion, and exemplifies the capabilities of the race.

She composed this verse: --

"'Twas mercy brought me from my pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God -- that there's a Saviour too;

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew."

Page 28

Contrary to the Connecticut slaveholder's feigned unbelief in the intellectual capacity of the Negro, and their assertions of his utter inferiority in all things, they early enacted the most rigid laws prohibiting the teaching of any Negro to read, bond or free, with a penalty of several hundred dollars for every such act. The following undeniable story is woven into the fabric of Connecticut's history, and tells a sad tale of the prejudice of her people against the Negro during the days of slavery there:

"Prudence Crandall a young Quaker lady of talent was employed to teach a 'boarding and day-school.' While at her post of duty one day, Sarah Harris, whose father was a well-to-do colored farmer, applied for admission. Miss Crandall hesitated somewhat to admit her, but knowing the girl's respectability, her lady-like and modest deportment, for she was a member of the white people's church and well known to them, she finally told her yes. The girl came. Soon Miss Crandall was called upon by the patrons, announcing their disgust and loathing that their daughters should attend school with a 'nigger girl.' Miss Crandall protested, but to no avail. The white pupils were finally taken from the school. Miss Crandall then opened a school for colored ladies. She enrolled about twenty, but they were subjected to many outrageous insults.

Page 29

They were denied accommodation altogether in the village of Canterbury. Their well was filled up with trash, and all kinds of unpleasant and annoying acts were thrust upon them. The people felt determined that Canterbury should not have the disgrace of a colored school. No, not even the State of Connecticut. Miss Crandall sent to Brooklyn to some of her friends. They plead in her behalf privately, and went to a town meeting to speak for her, but were denied the privilege. Finally, the Legislature passed a law prohibiting colored schools in the State. From the advice of her friends and her own strong will, Miss Crandall continued to teach. She was arrested and her friends were sent for. They came, but would not be persuaded by the sheriff and other officers to stand her bond. The people saw the disgrace and felt ashamed to have it go down in history that she was put in jail. In agreement with Miss Crandall's wishes her friends still persisted, so about night she was put in jail, into a murderer's cell. The news flashed over the country, much to the Connecticut people's chagrin and disgrace. She had her trial -- the Court evaded giving a decision. She opened her school again, and an attempt was made to burn up the building while she and the pupils were there, but proved unsuccessful. One night about midnight

Page 30

they were aroused to find themselves besieged by persons with heavy iron bars and clubs breaking the windows and tearing things to pieces. It was then thought unwise to continue the school longer. So the doors were closed and the poor girls, whose only offense was a manifestation for knowledge, were sent to their homes. This law, however, was repealed in 1838, after lasting five years.

Page 31

CHAPTER V.

NEW HAMPSHIRE AND MARYLAND.

New Hampshire slaves were very few in number. The people of this colony saw the evils of slavery very early and passed laws against their importation. Massachusetts was having so much trouble with her slaves that the New Hampshire people early made up their minds that, as a matter of business, as well as of humanity, they had best not try to build up their colony by dealing in human flesh and blood.

Maryland was, up to 1630, a part of Virginia, and slavery there partook of the same features. Owing to the feeling existing in the colony between the Catholics who planted it, and the Protestants, the slaves were treated better than in some other provinces. Yet their lot was a hard one at best; by law a white person could kill a slave and not suffer death; only pay a fine.

White Slaves existed in this colony, many of whom came as criminals from England. They, it seems, were chiefly domestic servants, while the Negroes worked the tobacco fields.

Page 32

BENJAMIN BANNEKA, ASTRONOMER AND MATHEMATICIAN.

Banneka was born in Maryland in the year 1731. An English woman named Molly Welsh, who came to Maryland as an emigrant, is said to have been his maternal grandmother. This woman was sold as a slave to pay her passage to this country on board an emigrant ship; and after serving out her term of slavery she bought two Negro slaves herself. These slaves were men of extraordinary powers, both of mind and body. One of them, said to be the son of an African king, was set free by her, and she soon married him. There were four children, and one of them, named Mary, married a native African, Robert Banneka, who was the father of Benjamin.

The School Days of young Benjamin were spent in a "pay school" where some colored children were admitted. The short while that Benjamin was there he learned to love his books, and when the other children played he was studying. He was very attentive to his duties on his father's farm, and when through with his task of caring for the horses and cows, he would spend his leisure hours in reading books and papers on the topics of the day.

Page 33

The Post-Office was the famous gathering place in those days, and there it was that young Benjamin was accustomed to go. He met many of the leading people of the community and fluently discussed with them difficult questions. He could answer almost any problem put to him in mathematics, and became known throughout the colonies as a genius. Many of his answers to questions were beyond the reach of ordinary minds.

Messrs. Ellicott & Co., who built flour mills on the Patapsco River near Baltimore, very early discovered Banneka's genius, and Mr. George Ellicott allowed him the use of his library and astronomical instruments. The result of this was that Benjamin Banneka published his first almanac in the year 1792, said to be the first almanac published in America. Before that he had made numerous calculations in astronomy and constructed for himself a splendid clock that, unfortunately, was burned with his dwelling soon after his death.

Banneka's Reputation spread all over America and even to Europe. He drew to him the association of the best and most learned men of his country. His ability was a curiosity to everybody, and did much to establish the fact that the Negro of his time could master the arts and sciences. It is said that he was the master of five different languages,

Page 34

as well as a mathematical and astronomical genius. He accompanied and assisted the commissioners who surveyed the District of Columbia.

He sent Mr. Thomas Jefferson one of his almanacs, which Mr. Jefferson prized so highly he sent it to Paris and wrote Mr. Banneka the following letter in reply. Along with Mr. Banneka's almanac to Mr. Jefferson, he sent a letter pleading for better treatment of the people of African descent in the United States.

MR. JEFFERSON'S LETTER TO B. BANNEKA.

"PHILADELPHIA, August 30th, 1791.

"Dear Sir:

-- I thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th instant, and for the almanac it contained. Nobody wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit that Nature has given to our black brethren talents equal to those of the other colors of men, and that the appearance of a want of them is owing only to the degraded condition of their existence, both in Africa and America. I can add with truth, that no one wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body and mind, to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecility of their present existence, and other circumstances which cannot be neglected, will admit. I have taken the liberty of

Page 35

sending your almanac to Monsieur de Cordorat, Secretary of the Academy of Sciences at Paris and member of the Philanthropic Society, because I considered it a document to which your whole color had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them.

"I am, with great esteem, sir,

"Your most obedient servant,

"THOS. JEFFERSON."

Mr. Benjamin Banneka, near Ellicott'sLower Mills, Baltimore County.

The Personal Appearance of Mr. Banneka is drawn from the letters of those who wrote about him. A certain gentleman who met him at Ellicott's Mills gives this description: "Of black complexion, medium stature, of uncommonly soft and gentlemanly manners, and of pleasing colloquial powers."

Mr. Banneka died about the year 1804, very greatly mourned by the people of this country and Europe. He left two sisters, who, according to his request, turned over his books, papers and astronomical calculations to Mr. Ellicott. There has been no greater mind in the possession of any American citizen than that of Benjamin Banneka. He stands out in history as one of those phenomenal characters whose achievements seem to be nothing short of miraculous.

Page 36

Francis Ellen Watkins was another of Maryland's bright slaves. She distinguished herself as an anti-slavery lecturer in the Eastern States, and wrote a book entitled, "Poems and Miscellaneous Writings: By Francis Ellen Watkins." In that book was the following poem entitled, "Ellen Harris":

(1) Like a fawn from the arrow, startled and wild,

A woman swept by me bearing a child;

In her eye was the night of a settled despair,

And her brow was overshadowed with anguish and care.

(2) She was nearing the river, -- on reaching the brink

She heeded no danger, she paused not to think!

For she is a mother -- her child is a slave, --

And she'll give him his freedom or find him a grave!

(3) But she's free, -- yes, free from the land where the slave

From the hand of oppression must rest in the grave;

Where bondage and torture, where scourges and chains,

Have placed on our banner indelible stains.

(4) The blood-hounds have missed the scent of her way;

The hunter is rifled and foiled of his prey;

Fierce jargon and cursing, with clanking of chains,

Make sounds of strange discord on Liberty's plains.

(5) With the rapture of love and fullness of bliss,

She placed on his brow a mother's fond kiss, --

Oh! poverty, danger and death she can brave,

For the child of her love is no longer a slave!

Page 37

CHAPTER VI.

DELAWARE AND PENNSYLVANIA.

Delaware was settled, as you will remember, by the Swedes and Danes in 1639. They were a simple, contented and religious people. It is recorded that they had a law very early in their history declaring it was "not lawful to buy and keep slaves." It is very evident, though, that later on in the history of the colony slaves were held, and their condition was the same as in New York. While the north of the colony was perhaps fully in sympathy with slavery, the western part was influenced by the religious sentiment of the Quakers in Pennsylvania.

The Friends of Pennsylvania were opposed to slavery, and although slavery was tolerated by law, the way was left open for their education and religious training. In 1688 Francis Daniel Pastorious*

*Williams.

addressed a memorial to the Friends of Germantown. His was said to be the first protest against slavery made by any of the churches of America. He believed that "slave and slave-owner should be equal at the Master's feet."

William Penn showed himself friendly to the slaves.

Page 38

CHAPTER VII.

NORTH CAROLINA.

This colony in geographical position lies between South Carolina and Virginia, While it held slaves, it may be justly said its position on this great question was not so burdensome to the slave as the other Southern colonies, and even to the present time the Negroes and whites of this State seem to enjoy the most harmonious relations. The slave laws of this State gave absolute dominion of the master over the servant, but allowed him to join the churches from the first. Large communities of free Negroes lived in this State prior to the civil war and for a long time could vote. They had some rights of citizenship and many of them became men of note.

Prior to the Civil War there were schools for these free people. Some of them owned slaves themselves. In this colony the slaves were worked as a rule on small farms and there was a close relation established between master and slave, which bore its fruits in somewhat milder treatment than was customary in colonies where the slaves lived on

Page 39

large cotton plantations governed by cruel overseers, some of whom were imported from the North.

The Eastern Section of North Carolina was thickly peopled with slaves, and some landlords owned as many as two thousand.

The increase and surplusage of the slave population in this State was sold to the more Southern colonies, where they were used on the cotton plantations.

A NORTH CAROLINA SLAVE POET.

George M. Horton was his name. He was the slave of James M. Horton, of Chatham County, N. C. Several of his special poems were published in the Raleigh Register. In 1829, A. M. Gales, of this State, afterwards of the firm of Gales & Seaton, Washington, D. C., published a volume of the slave Horton's poems which excited the wonder and admiration of the best men in this country. His poems reached Boston where they were much talked of and used as an argument against slavery. Horton, at the time his volume was published, could read but not write, and was, therefore, compelled to dictate his productions to some one who wrote them down for him. He afterwards learned to write. He seemed to have concealed all his achievements from his master, who knew nothing of his slave's ability

Page 40

except what others told him. He simply knew George as a field-hand, which work he did faithfully and honestly, and wrote his poetry too. Though a slave, his was a noble soul inspired with the Muse from above. The Raleigh Register said of him, July 2d, 1829: "That his heart has felt deeply and sensitively in this lowest possible condition of human nature (meaning slavery), will be easily believed and is impressively confirmed by one of his stanzas, viz.:

"Come melting pity from afar,

And break this vast, enormous bar

Between a wretch and thee:

Purchase a few short days of time,

And bid a vassal soar sublime

On wings of Liberty."

Page 41

CHAPTER VIII.

SOUTH CAROLINA.

Charters for the Settlement of North and South Carolina were obtained at the same time -- 1663. Slavery commenced with the colony. Owing to the peculiar fitness of the soil for the production of rice and cotton, slave labor was in great demand. White labor failed, and the colony was marvelously prosperous under the slave system. Negroes were imported from Africa by the thousands. Their labor proved very productive, and here it was that the slave code reached its maximum of harshness.

A Negro Regiment in the service of Spain was doing duty in Florida, and through it the Spanish, who were at dagger's ends with the British colonies, sent out spies who offered inducements to such of the South Carolina slaves as would runaway and join them. Many slaves ran away. Very rigid and extreme laws were passed to prevent slaves from running away, such as branding and cutting the "ham-string" of the leg.

A Riot followed the continued cruel treatment of slaves under the runaway code; 1748 is said to have been the year in which a crowd of slaves assembled in

Page 42

the village of Stono, slew the guards at the arsenal and secured the ammunition there. They then marched to the homes of several leading men whom they murdered, together with their wives and children. The slaves captured considerable rum in their plundering expedition, and having indulged very freely stopped for a frolic, and in the midst of their hilarity were captured by the whites, and thus ended the riot.

The Discontent of the Slaves grew, however, in spite of the speedy ending of this attempt at insurrection. Cruel and inhuman treatment was bearing its fruits in a universal dissatisfaction of the slaves, and in South Carolina, as in Massachusetts, it began to be a serious question as to what side the slaves would take in the war of the coming Revolution. England offered freedom and money to slaves who would join her army. The people of South Carolina did not wait long before they allowed the Negroes to enlist in defence of the colonies, and highly complimented their valor. If a slave killed a Briton he was emancipated; if he were taken prisoner and escaped back into the Province he was also set free.

Page 43

CHAPTER IX.

GEORGIA.

From the time of its settlement in 1732 till 1750 this colony held no slaves. Manyof the inhabitants were anxious for the introduction of slaves, and when the condition of the colony finally became hopeless they sent many long petitions to the Trustees, stating that "the one thing needful" for their prosperity was Negroes. It was a long time before the Trustees would give their consent; they said that the colony of Georgia was designed to be a protection to South Carolina and the other more Northern colonies against the Spanish, who were then occupying Florida, and if the colonists had to control slaves it would weaken their power to defend their colonies. Finally, owing to the hopeless condition of the Georgia colony, the Trustees yielded. Slaves were introduced in large numbers.

Prosperity came with the slaves, and, as in the case of Virginia, the colony of Georgia took a fresh start and began to prosper. White labor proved a failure. It was the honest and faithful toil of the Negro that turned the richness of Georgia's soil into English gold, built cities and created large

Page 44

estates, gilded mansions furnished with gold and silver plate.*

* The famous minister, George Whitfield, referring to his plantation in this colony, said: "Upward of five thousand pounds have been expended in the undertaking, and yet very little proficiency made in the cultivation of my tract of land, and that entirely owing to the necessity I lay under of making use of white hands. Had a Negro been allowed I should now have had a sufficiency to support a great many orphans, without expending above half the sum which has been laid out." He purchased a plantation in South Carolina, where slavery existed, and speaks of it thus: "Blessed be God! This plantation has succeeded; and though at present I have only eight working hands, yet, in all probability, there will be more raised in one year, and without a quarter of the expense, than has been produced at Bethesda for several years past. This confirms me in the opinion I have entertained for a long time, that Georgia never can or will be a flourishing province without Negroes are allowed."

Oglethorpe Planned the Georgia colony as a home for Englishmen who had failed in business and were imprisoned for their debts. These English people were out of place in the wild woods of America, and continued a failure in America, as well as in England, until the toiling but "heathen" African came to their aid.

Cotton Plantations were numerous in Georgia under the slave system. The slave-owners had large estates, numbering thousands of acres in many cases. The slaves were experts in the culture of cotton. The climate was adapted to sugarcane and rice, both of which were raised in abundance.

BLOUNT'S FORT.

This fortification, erected by some of the armies during the early colonial wars, had been abandoned.

Page 45

It lies on the west bank of the Apalachicola River in Florida, forty miles from the Georgia line. Negro refugees from Georgia fled into the everglades of Florida as a hiding-place during the war of the Revolution. In these swamps they remained for forty years successfully baffling all attempts to re-enslave them. Many of those who planned the escape at first were now dead, and their children had grown up to hate the lash and love liberty. Their parents had taught them that to die in the swamps with liberty was better than to feast as a bondman and a slave. When Blount's Fort was abandoned and taken possession of by these children of the swamp, there were three hundred and eleven of them, out of which not more than twenty had ever been slaves. They were joined by other slaves who ran away as chance permitted. The neighboring slave-holders attempted to capture these people but failed. They finally, called on the President of the United States for aid. General Jackson, then commander of the Southern militia, delegated Lieutenant Colonel Clinch to take the Fort and reduce these people to slavery again. His sympathies being with the refugees, he marched to the fort and returned, reporting that "the fortification was not accessible by land."

Commodore Patterson next received orders. He

Page 46

commanded the American fleet then lying In Mobile Bay. A "sub-order was given instantly to Lieutenant Loomis to ascend the Apalachicola River with two gun-boats, to seize the people in Blount's Fort, deliver them to their owners, and destroy the fort." At early dawn on the morning of September the 17th, 1816, the two boats, with full sail catching a gentle breeze, moved up the river towards the fort. They lowered a boat on their arrival and twelve men went ashore. They were met at the water's edge and asked their errand by a number of the leading men of the fort. Lieutenant Loomis informed them that he came to destroy the fort and turn over its inmates to the "slave-holders, then on board the gun-boat, who claimed them as fugitive slaves." The demand was rejected. The colored men returned to the fort and informed the inmates. Great consternation prevailed. The women were much distressed, but amid the confusion and excitement there appeared an aged father whose back bore the print of the lash, and whose shoulder bore the brand of his master. He assured the people that the fort could not be taken, and ended his speech with these patriotic words: "Give me liberty, or give me death." The shout went up from the entire fort as from one man, and they prepared to face the enemy.

The Gun-boats Soon Opened Fire. For several

Page 47

hours they buried balls into the earthen walls and injured no one. Bombs were then fired. These had more effect, as there was no shelter from them. Mothers were more careful to hug their young babies closer to their bosoms. All this seemed little more than sport for the inmates of the fort, who saw nothing but a joke in it after shelter had been found.

Lieutenant Loomis saw his failure. He had a consultation and it was agreed to fire "hot shot at the magazine." So the furnaces were heated and the fiery flames began to whizz through the air. This last stroke was effectual, the hot shot set the magazine on fire and a terrible explosion covered the entire place with debris. Many were instantly killed by the falling earth and timbers. The mangled limbs of mothers and babies lay side by side. It was now dark. Fifteen persons in the fort had survived the explosion. The sixty sailors and officers now entered, trampling over the wounded and dying, and took these fifteen refugees in handcuffs and ropes back to the boats. The dead, wounded and dying were left.

As the two boats moved away from this scene of carnage the sight weakened the veteran sailors on board the boats, and when the officers retired the weather-worn sailors "gathered before the mast, and loud and bitter were the curses uttered against

Page 48

slavery and against the officers of the government who had thus constrained them to murder innocent women and helpless children, merely for their love of liberty."

The Dead Remained unburied in the fort. The wounded and dying were not cared for and all were left as fat prey for vultures to feast upon. For fifty years afterward the bones of these brave people lay bleaching in the sun. Twenty years after the murder a Representative in Congress from one of the free States introduced a bill giving a gratuity to the perpetrators of this crime. The bill passed both houses.

Having briefly considered the establishment of slavery in the colonies, where the Negro slave was employed in every menial occupation, and where he accepted the conditions imposed upon him with a full knowledge of the wrong done, but still jubilant with songs of hope for deliverance, and trust in God whose promises are many to the faithful, let us turn to

The War of the Revolution which soon came on; and in it Providence no doubt designed an opportunity for the race to loosen up the rivets in the chains that bound them. They made good of this opportunity.

Page 49

CHAPTER X.

HABITS AND CUSTOMS OF THE SOUTHERN

COLONIES.

Barnes Gives the following account of the habits and customs of the Southern colonies during the days of slavery:

"The Southern Colonists differed widely from the Northern in habits and style of living. In place of thickly settled towns and villages, they had large plantations, and were surrounded by a numerous household of servants. The Negro quarters formed a hamlet apart, with its gardens and poultry yards. An estate in those days was a little empire. The planter had among his slaves men of every trade, and they made most of the articles needed for common use upon the plantation. There were large sheds for curing tobacco, and mills for grinding corn and wheat. The tobacco was put up and consigned directly to England. The flour of the Mount Vernon estate was packed under the eye of Washington himself, and we are told that barrels of flour bearing his brand passed in the West India market without inspection.

Page 50

"Up the Ashley and Cooper (near Charleston), were the remains of the only bona fide nobility ever established on our soil. There the descendants of the Landgraves, who received their title in accordance with Locke's grand model, occupied their manorial dwellings. Along the banks of the James and Rappahannock, the plantation often passed from father to son, according to the law of entail.

"The heads of these great Southern families lived like lords, keeping their packs of choice hunting dogs, and their stables of blooded horses, and rolling to church or town in their coach of six, with outriders on horseback. Their spacious mansions were sometimes built of imported brick. Within, the grand staircases, the mantels, and the wainscot, reaching in a quaint fashion from floor to ceiling were of mahogany elaborately carved and paneled. The sideboards shone with gold and silver plate and the tables were loaded with the luxuries of the Old World. Negro servants thronged about, ready to perform every task.

"All Labor was done by Slaves, it being considered degrading for a white man to work. Even the superintendence of the plantation and slaves was generally committed to overseers, while the master dispensed a generous hospitality, and occupied himself with social and political life."

Page 51

SLAVERY INTRODUCED IN THE COLONIES

- In Virginia, the last of August, 1619.

- In New York, 1628.

- In Massachusetts, 1637.

- In Maryland, 1634.

- In Delaware, 1636.

- In Connecticut, between 1631 and 1636.

- In Rhode Island from the beginning, 1647.

- New Jersey, not known, as early, though, as in New Netherland.

- South Carolina and North Carolina from the earliest days of existence.

- In New Hampshire, slavery existed from the beginning.

- Pennsylvania doubtful.

Page 52

CHAPTER XI.

NEGRO SOLDIERS IN REVOLUTIONARY

TIMES.

Objections to Enlisting Negroes caused much discussion at the beginning of the Revolutionary war. The Northern colonies partially favored their enlistment because they knew of their bravery, and rightly reasoned that if the Negroes were not allowed to enlist in the Colonial army, where their sympathies were, they would accept the propositions of the British, who promised freedom to every slave who would desert his master and join the English army.

Lord Dunmore, Governor of Virginia, and the other British leaders, saw a good chance to weaken the strength of the colonies by offering freedom to the slaves if they would fight for England. They knew that the slaves would be used to throw up fortifications, do fatigue duties, and raise the provisions necessary to support the Colonial army. So Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation offering freedom to all slaves who would join his army. As the result of this, Thomas Jefferson is quoted as

Page 53

saying 30,000 Negroes from Virginia alone joined the British ranks.

The Americans became fearful of the results that were sure to follow the plans of Lord Dunmore. Sentiment began to change in the Negro's favor; the newspapers were filled with kind words for the slaves, trying to convince them that the British Government had forced slavery upon the colonies against their will, and that their best interests were centred in the triumph of the Colonial army. A part of an article in one paper, headed "Caution to the Negro," read thus: "Can it, then, be supposed that the Negroes will be better used by the English, who have always encouraged and upheld this slavery, than by their present masters, who pity their condition; who wish in general to make it as easy and comfortable as possible, and who would, were it in their power, or were they permitted, not only prevent any more Negroes from losing their freedom, but restore it to such as have already unhappily lost it. * * * They will send the Negroes to the West Indies where every year they sell many thousands of their miserable brethren. Be not tempted, ye Negroes, to ruin yourselves by this proclamation." The colonies finally allowed the enlistment of Negroes, their masters being paid for them out of the public treasury. Those slaves

Page 54

who had already joined the British were offered pardon if they would escape and return, and a severe punishment was to be inflicted on those who left the colony if they were caught.

To Offset the Plans of Lord Dunmore, the Americans proposed to organize a Negro army to be commanded by the brave Col. Laurens; and on this subject the following letter was addressed to John Jay, President of Congress, by the renowned Alexander Hamilton. This letter also shows in what esteem the Negro slave of America was held by men of note:

"HEADQUARTERS, March 14, 1779.

"To John Jay.

"DEAR SIR: Col. Laurens, who will have the honor of delivering you this letter, is on his way to South Carolina on a project which I think, in the present situation of affairs there, is a very good one, and deserves every kind of support and encouragement. This is to raise two, or three, or four battalions of Negroes, with the assistance of the government of that State, by contributions from the owners in proportion to the number they possess. If you think proper to enter upon the subject with him, he will give you a detail of his plan. He wishes to have it recommended by Congress

Page 55

and the State, and, as an inducement, they should engage to take those battalions into Continental pay.

"It appears to me that an expedient of this kind, in the present state of Southern affairs, is the most rational that can be adopted and promises very important advantages. Indeed, I hardly see how a sufficient force can be collected in that quarter without it, and the enemy's operations are growing infinitely more serious and formidable. I have not the least doubt that the Negroes will make very excellent soldiers with proper management; and I will venture to pronounce that they cannot be put in better hands than those of Mr. Laurens. He has all the zeal, intelligence, enterprise, and every other qualification necessary to succeed in such an undertaking. It is a maxim with some great military judges that, "with sensible officers, soldiers can hardly be too stupid"; and, on this principle, it is thought that the Russians would make the best troops in the world if they were under other officers than their own. I mention this, because I hear it frequently objected to, the scheme of embodying Negroes, that they are too stupid to make soldiers. This is so far from appearing, to me, a valid objection, that I think their want of cultivation (for their natural faculties are probably as good as ours),

Page 56

joined to that habit of subordination from a life of servitude, will make them sooner become soldiers than our white inhabitants. Let officers be men of sense and sentiment, and the nearer the soldiers approach to machines perhaps the better.

"I foresee that this project will have to combat much opposition from prejudice and self-interest. The contempt we have been taught to entertain for the blacks, makes us fancy many things that are founded neither in reason nor experience, and an unwillingness to part with property of so valuable a kind will furnish a thousand arguments to show the impracticability or pernicious tendency of a scheme which requires such a sacrifice. But it should be considered that if we do not make use of them in this way the enemy probably will; and that the best way to counteract the temptations they hold out will be to offer them ourselves. An essential part of the plan is to give them their freedom with their muskets. This will secure their fidelity, animate their courage, and, I believe, will have a good influence upon those who remain by opening the door to their emancipation. This circumstance, I confess, has no small weight in inducing me to wish the success of the project, for the dictates of humanity and true policy equally

Page 57

interest me in favor of this unfortunate class of men. With the truest respect and esteem, I am, sir, Your most obedient servant,

"ALEX. HAMILTON."

George Washington, James Madison, and the Continental Congress gave their consent to the plan of Col. Laurens, and recommended it to the Southern colonies. It was resolved by Congress to compensate the master for the slaves used by Col. Laurens at the rate of $1,000 apiece for each "able-bodied negro man of standard size, not exceeding thirty-five years of age, who shall be so enlisted and pass muster. That no pay be allowed to the said Negroes, but that they be clothed and subsisted at the expense of the United States; that every Negro who shall well and faithfully serve as a soldier to the end of the present war, and shall then return his arms, shall be emancipated and receive the sum of fifty dollars."

Congress commissioned Col. Laurens to carry out this plan. "He repaired to South Carolina and threw all his energies into his noble mission." The people of the States of Georgia and South Carolina refused to co-operate with him. It was difficult to get white troops to enlist. The Tories, who opposed the war against England,

Page 58

were very strong in several of the Southern colonies.

A Letter from General Washington will help us to understand the condition of affairs in South Carolina and Georgia. He wrote to Col. Laurens, as follows: "I must confess that I am not at all astonished at the failure of your plan. That spirit of freedom which, at the commencement of this contest, would have gladly sacrificed everything to the attainment of its object, has long since subsided, and every selfish passion has taken its place. It is not the public but private interest which influences the generality of mankind, nor can the Americans any longer boast an exception. Under these circumstances it would rather have been surprising if you had succeeded, nor will you, I fear, have better success in Georgia."

Col. Laurens was killed in battle, but he had not entirely abandoned his plan of enlisting the slaves. But in spite of the recommendations of Congress he could not succeed, for the States of South Carolina and Georgia coveted their slaves too much to allow this entering wedge to their ultimate freedom. Had his plan been carried out slavery would probably have been abolished as soon at the South as at the North. The Negroes who would have come out of the war of the Revolution, would have set themselves

Page 59

to work to relieve the condition of their brethren in shackles.

Connecticut Failed to endorse the enlistment of Negroes by its Legislature, but Mr. Williams in his history gives the roster of a company of Negroes in that State, numbering fifty-seven, with David Humphreys Captain. White officers refused to serve in the company. David Humphreys continued at the head of this force until the war closed.

Page 60

CHAPTER XII.

NEGRO HEROES OF THE REVOLUTION.

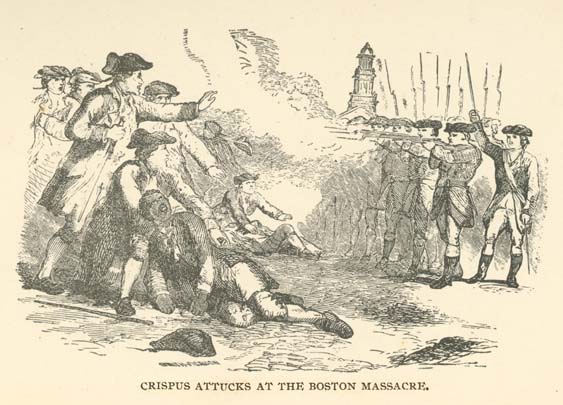

Among Those whose blood was first shed for the cause of American liberty was the runaway slave, Crispus Attucks. Having escaped from his master, William Brown, of Framingham, Massachusetts, at the age of twenty-seven, being then six feet two inches high, with "short, curled hair," he made his way to Boston. His master in 1750 offered a reward of ten pounds for him, but Crispus was not found. When next heard from he turns up in the streets of Boston.

THE LEADER WHO FELL IN THE FAMOUS BOSTON MASSACRE.

Attucks had no doubt been listening to the fiery eloquence of the patriots of those burning times. The words of the eloquent Otis had kindled his soul, and though a runaway slave, his patriotism was so deep that he it was who sacrificed his life first on the altar of American Liberty.

General Gage, the English commander, had taken possession of Boston. Under the British flag gaily

Page 61

CRISPUS ATTUCKS AT THE BOSTON MASSACRE.

Page 62

dressed soldiers marched the streets of Boston as through a conquered city; their every act was an insult to the inhabitants. Finally, on March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks, at the head of a crowd of citizens, resolved no longer to be insulted, and determining to resist any invasion of their rights as citizens, a fight soon ensued on the street. The troops were ordered to fire on the "mob," and Attucks fell, the first one, with three others, Caldwell, Gray, and Maverick, The town bell was rung, the alarm given and citizens from the country ran into Boston, where the greatest excitement prevailed.

The Burial of Attucks, the only unknown dead, was from Faneuil Hall. The funeral procession was enormous, and many of the best citizens of Boston readily followed this former slave and unknown hero to an honored grave. Many orators spoke in the highest terms of Crispus Attucks. A verse mentioning him reads thus:

"Long as in freedom's cause the wise contend,

Dear to your country shall your fame extend;

While to the world the lettered stone shall tell

Where Caldwell, Attucks, Gray and Maverick fell."

Page 63

PETER SALEM SHOOTS MAJOR PITCAIRN AT BUNKER HILL.

Bunker Hill was the scene of a brave deed by a Negro soldier. Major Pitcairn was commander of the British forces there. The battle was fierce; victory seemed sure to the English, when Pitcairn mounted an eminence, shouting triumphantly, "The day is ours!" At this moment the Americans stood as if dumfounded, when suddenly, with the leap of a tiger, there rushed forth Peter Salem, who fired directly at the officer's breast and killed him. Salem was said to have been a slave, of Framingham, Massachusetts. Gen. Warren, who was killed in this battle, greatly eulogized Crispus Attucks for his bravery in Boston, and had he not been stricken down so soon, Peter Salem would

Page 64

doubtless also have received high encomiums from his eloquent lips.

Five Thousand Negroes are said to have fought on the side of the colonies during the Revolution. Most of them were from the Northern colonies. There were, possibly, 50,000 Negroes enlisted on the side of Great Britain, and 30,000 of these were from Virginia.

SOME INDIVIDUALS OF REVOLUTIONARY TIMES.

Primus Hall was body servant of Col. Pickering in Massachusetts. Gen. Washington was quite intimate with the Colonel and paid him many visits. On one occasion Washington continued his visit till a late hour, and being assured by Primus that there were blankets enough to accommodate him, he resolved, to spend the night in the Colonel's quarters. Accordingly, two beds of staw were made down and Washington and Col. Pickering retired, leaving Primus engaged about the tent. Late in the night Gen. Washington awoke, and seeing Primus sitting on a box nodding, rose up in his bed and said: "Primus, what did you mean by saying that you had blankets enough? Have you given up your blanket and straw to me, that I may sleep comfortable while you are obliged to sit through the night?"

Page 65

"It's nothing," said Primus; "don't trouble yourself about me, General, but go to sleep again. No matter about me; I sleep very good." "But it is matter; it is matter," replied Washington, earnestly. "I cannot do it, Primus. If either is to sit up, I will. But I think there is no need of either sitting up. The blanket is wide enough for two. Come and lie down here with me." "O, no, General," said Primus; "let me sit here; I'll do very well on the box." Washington said, "I say come and lie down here! There is room for both, and I insist upon it;" and as he spoke he threw up the blanket and moved to one side of the straw. Primus hesitated, but Washington continuing to insist, Primus finally prepared himself and laid down by Washington, and on the same straw, and under the same blanket, where the General and the Negro servant slept till morning.

Washington is said to have been out walking one day in company with some distinguished gentlemen, and during the walk he met an old colored man who very politely tipped his hat and spoke to the General. Washington in turn took off his hat to the colored man, on seeing which one of the company in a jesting manner inquired of the General if he usually took off his hat to Negroes. Whereupon Washington replied: "Politeness is

Page 66

cheap, and I never allow any one to be more polite to me than I to him."

BRAVE COLORED ARTILLERYMAN.

Judge Story gives an account of a colored artilleryman who was in charge of a cannon with a white soldier at Bunker Hill. He had one arm so badly wounded he could not use it. He suggested to the white soldier that he change sides so as to use the other arm. He did this, and while thus laboring under pain and loss of blood a shot came which killed him.

Prince ------ appears in the attempt to capture General Prescott of the Royal army stationed at Newport, R. I. General Lee of the American forces was held as a prisoner by the British, and it

Page 67