Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry from 1864 to 1914.

Twenty-seven Years in the Pastorate; Sixteen Years' Active Service as Chaplain

in the U. S. Army; Seven Years Professor in Wilberforce University;

Two Trips to Europe; A Trip in Mexico:

Electronic Edition.

Steward, T. G. (Theophilus Gould), 1843-1924

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Andrew Leiter

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Andrew Leiter, and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2001

ca. 760K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry from 1864 to 1914. Twenty-seven Years in the Pastorate; Sixteen Years' Active Service as Chaplain in the U. S. Army; Seven Years Professor in Wilberforce University; Two Trips to Europe; A Trip in Mexico.

(cover) Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry

Theophilus Gould Steward

521 p., ill.

Phila., Pa.

Printed by A. M. E. Book Concern

[1921?]

Call number BX8449.S74 A3 (Davis Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

- French

- Italian

- Spanish

- German

LC Subject Headings:

- African American clergy -- United States -- Biography.

- African American Methodists -- Biography.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- Clergy -- Biography.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- History.

- Chaplains, Military -- United States -- Biography.

- Europe -- Description and travel.

- Steward, T. G. (Theophilus Gould), 1843-1924.

- United States. Army -- Chaplains -- Biography.

Revision History:

- 2001-08-28,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-03-22,

Jill Kuhn Sexton, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-03-02,

Andrew Leiter

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-01-20,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcription.

Chaplain T. G. Steward

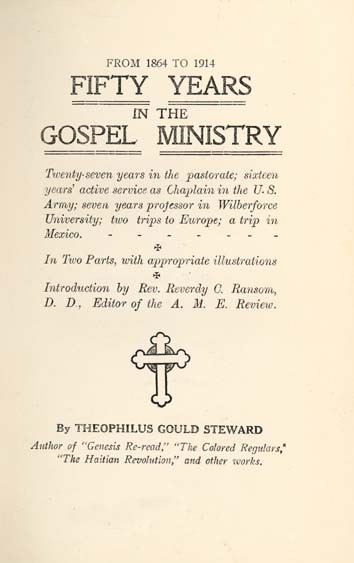

FROM 1864 TO 1914

FIFTY YEARS

IN THE

GOSPEL MINISTRY

Twenty-seven years in the pastorate; sixteen

years' active service as Chaplain in the U.S.

Army; seven years professor in Wilberforce

University; two trips to Europe; a trip in

Mexico.

In Two Parts, with appropriate illustrations.

Introduction by Rev. Reverdy C. Ransom, D. D., Editor of the A. M. E. Review.

By

THEOPHILUS GOULD STEWARD

Author of "Genesis Re-read," "The Colored Regulars,"

"The Haitian Revolution," and other works.

Page verso

PRINTED BY

A. M. E. Book Concern

631 Pine Street

Phila., Pa.

Page iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PART I.

- CHAPTER I.

- GENERAL CONFERENCE OF 1864: Bishops Quinn, Payne and Nazrey. Captain Robert Smalls; Chaplain H. M. Turner; Rev. James Lynch. Bishops Campbell and Wayman elected Annual Conference in Salem, N. J. Bishop Wayman preaches; Rev. W. H. W. Winder faints in the pulpit. Rev. A. L. Stanford preaches; My first appointment; First visit to New York; Sail to Charleston, S. C.; Organization of South Carolina Conference; Ordination--appointment. Companions; Revs. James A. Handy; J. H. A. Johnson, etc. Organization of church in Beaufort; First Sermon.

- CHAPTER ll.

- SECOND TRIP SOUTH: Captain Walls; Miss Jennie Lynch; Experience with discharged soldier--Georgetown; Rev. A. T. Carr; Summerville, Mrs. Parker; Col. Thos. K. Beecher--Courtship and marriage. Experiences in Marion, S. C. A fight between an ex-slaveholder and a freedman; New England Provost Marshal--Organize a church; Criminal in jail calls me; Haunted house; Illiteracy; Second Conference in Savannah; Native preachers; Rev. W. J. Gaines; Andrew Brown. Revs. H. M. Turner and R. H. Cain. Extract from sermon and address at Marion, S. C., 1866.

- CHAPTER III.

- WORK IN CHARLESTON, S. C.:

Journey to Macon, Ga. Conference in that city. Return to Charleston--Trip by sea to Savannah. Robert

Page ivSmalls--Fourth of July in Macon, Ga.--Trip to Lumpkin, Ga.--Work there--Conference again in Macon--Appointment to the church in Macon.

- WORK IN CHARLESTON, S. C.:

Journey to Macon, Ga. Conference in that city. Return to Charleston--Trip by sea to Savannah. Robert

- CHAPTER IV.

- GENERAL CONFERENCE OF 1868: Delegates from the South--Revs. J. M. Brown, J. A. Shorter and T. M. D. Ward elected bishops. The union question of 1864. Beginning my work in Macon--Fine spirit in the church--a surprise--W. B. Campbell attempts revolt--New church built--Selling cotton; Freedman's Bank--Opening new church--W. J. Gaines succeeds me; Mrs. M. E. F. Smith--transfer North.

- CHAPTER V.

- MEETING OF THE PHILADELPHIA CONFERENCE: Trial of Rev. J. H. Turpin--Author's connection with it--First election of delegates to General Conference--Important measures introduced in General Conference of 1872. Appointment to Wilmington, Del. Condition of education in Delaware. Mission to Haiti--Return to Delaware--Assignment to Brooklyn--Criticism of Professor Huxley's lectures. Transferred to Philadelphia. Note: Brother Murray and Fleet Street Church.

- CHAPTER VI.

- WORK AT ZION MISSION CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA:

Rev. John H. Inskip and Mrs. Inskip; The Protestant Episcopal Divinity School--Experiences there--Duplicated by Rev. L. J. Coppin. Delegate to Gen. Conference of 1888; Case of Rev. R. H. Cain, Resolution against separate schools in Philadelphia. Second pastorate in Wilmington,

Page vDel. Dedication--Bishop Brown's "Episcopacy." The "mixed" school question. Appointed to Union Church, Philadelphia.

- WORK AT ZION MISSION CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA:

Rev. John H. Inskip and Mrs. Inskip; The Protestant Episcopal Divinity School--Experiences there--Duplicated by Rev. L. J. Coppin. Delegate to Gen. Conference of 1888; Case of Rev. R. H. Cain, Resolution against separate schools in Philadelphia. Second pastorate in Wilmington,

- CHAPTER VII.

- THE NEW UNION CHURCH, PHILADELPHIA: Annual report of Trustees--Conference of 1884--Case of John E. Davis--General Conference of 1884--Bishop Brown's "Dogmas"--Sermon on out-come of Cleveland--Blaine campaign. Remarkable conversion of young lady: "Oh it is grand to be trusting." Resolutions--Transfer to Metropolitan Church, Washington, D. C.

- CHAPTER VIII.

- DECDICATION OF METROPOLITAN CHURCH Pressing debt--Large building, Small membership. Spiritual people--Representative congregation--Excellent choir--Community work. Frederick Douglas' Confession of Faith. General Conference of 1888--Much discussion--Combinations; Bishop Turner and organic law. J. M. Henderson and the Ritual--Colored schools in Baltimore--Isaac Myers--A white man and his colored daughter in court-

- CHAPTER IX.

- APPOINTMENT AS CHAPLAIN IN THE ARMY:

Recommended by Honorable B. K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, and John Wanamaker--With Regiment in Montana--Reception--Col. George L. Andrews, Mrs. Andrews--Refused admission to a hotel dining room--protest--Commanding officer's attitude--settled--Regiment ordered to mobilize for Spanish-American War--Recruiting--Montauk

Page viPoint--Denver--Special order to write History of Colored Regulars--Ordered to the Phillipines.

- APPOINTMENT AS CHAPLAIN IN THE ARMY:

Recommended by Honorable B. K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, and John Wanamaker--With Regiment in Montana--Reception--Col. George L. Andrews, Mrs. Andrews--Refused admission to a hotel dining room--protest--Commanding officer's attitude--settled--Regiment ordered to mobilize for Spanish-American War--Recruiting--Montauk

- CHAPTER X.

- VOYAGE TO THE PHILIPPINES: Met with a fall--Services on board--Report to the Regiment at Bamban--Stay in Manila--My first social dinner with Filippinos--Close 1899 with a "Personal." School work in Zambales province--Devout catholics--Letter to Archbishop Chapelle--Filippinos. Paterno, Mabini; Poblete; Aguinaldo. Color on the transports--Color line world-wide; thoughts written in 1900.

- CHAPTER XI.

- COMING HOME: "Hail Columbia, Happy Land"--Stay in Fort Niobrara--Good reception by the people--No good hunting or fishing--Transfer to Texas--Brownsville; Did the soldiers shoot up the town? Retired--Settled in Wilberforce--Employed in the college; Continued to write--Published "Gouldtown" in Collaboration with my brother--Published "The Haitian Revolution." Summing up.

- CHAPTER I.

- PART II.

- CHAPTER I.

- EARLY DREAMS AND THEIR FULFILMENT: Crossing the Atlantic--Landing in Glasgow--A hard bed--The University--Art Gallery, etc.

- CHAPTER II.

- EDINBOROUGH: A religious family--The University--The land question--Palaces--Castle--Churches--Elevated civilization.

Page vii - CHAPTER III.

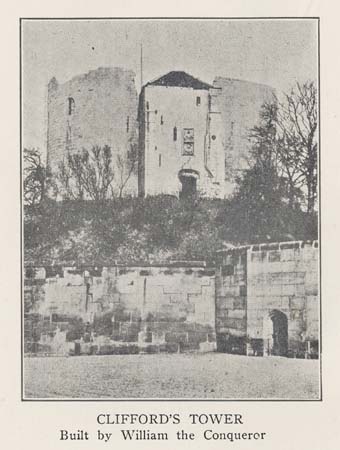

- YORK: Its history--Minster--St. Mary's Abbey--Roman remains. Sir Theodore Martin--A great life.

- CHAPTER IV.

- LONDON: History--Westminster--London Bridge--Hyde Park--Plenty of seats--Only a penny--Colored and white people walk streets together--Dinners--Military--How easy to visit parliament; Foundling Home.

- CHAPTER V.

- PARIS: To Dover, the English Channel--Genuine Corkscrew motion--Calais--To Paris--Gaiety and song--Versailles; Squares--The French woman--M. Pol and his birds--Law for married people.

- CHAPTER VI.

- SOUTHERN FRANCE: St. Etienne--Our Consul Mr. Hunt, and his wife--Auto trip up the Rhone--Sketch of the country.

- CHAPTER VII.

- TO ITALY AND HOME.

- CHAPTER I.

Page viii

ILLUSTRATIONS

- PART I.

- Frontispiece Author

- Early Portrait of same 22

- Author and Bride 64

- Steward A. M. E. Church 136

- M. E. F. Smith 139

- Margaret Sterling 160

- Bishop Campbell 192

- J. A. Simms 228

- Bishop Gaines 242

- Isaac Myers 265

- Colonel Andrews and Mrs. Andrews 269

- Chaplain Steward 273

- Elizabeth Gadsden Steward 281

- Doctor Steward 302

- PART II.

Page errata

The author regrets that despite his utmost care some errors have crept into this book. The important ones are corrected in the accompanying errata. Minor ones, which do not alter the sense the reader is asked to excuse.

ERRATA

Page

68 13th line from top, read filth for "fifth.

157 14th line from bottom read sociological for "theological."

175 16th line from top omit the word "no."

188 14th line from top read thought for "ought."

322 3rd line from the bottom, read Venido for Unido.

501 11th line from the bottom read prisons for "persons."

Page ix

FOREWORD

It is now 1921, and the story told in this book came to an end in fact seven years ago; and now standing upon the seventy-eighth terrace of the highland I have been ascending, I turn to look back and down upon the winding pathway by which I have come. The first flat terrace, so near sea level, seems not far away, and leaping over in vision the rising plateaus, the scenes of my youth, with the bright companions of those hours arise before me. The boys with whom I played ball, hunted, gathered nuts, skated and fished; the girls with their laughing faces whom we bashfully met at the various home parties, when the red apples were ripe; the quiet cheery grandmothers with their frilled caps; the busy mothers and daughters who baked the pies and fried the dough-nuts. Oh, but we were hungry boys then! And eating was a large part of our enjoyment. That was the morning of the day; the spring-tide of the year. I thank God for my youth. The country school; the Sunday school and the church made our triangle, and the circle that inscribed these included our home, family and community life.

Then next I see the terrace of decision. It is marked about the fifteenth, and stands out with

Page x

its plain sign-board. The dream of the sea with its romance and song; the book, "Jack Halliard," and stories told by sea faring men had set up in my mind a fairy picture. My first step in this direction left a disgusting damp upon my fervor. We were engaged in clearing a swamp; it was August; the days were hot and long; the work irksome; and I complained to my father. Fortunately he was a wise man and in a few days came in, making the announcement, "Theoph, I've got a job for you." "What is it?" "To go on the steamer Express." I should sail; I should see the city which I had never seen; I was happy. I went on board; a white apron was tied around me and I was shown how to stand and wait. The waiter's position then was not what it is now. About six days ended my apprenticeship; I came home, went back into the swamp to work; father never said anything to me nor I to him over the matter. I think he was immensely pleased with the outcome. I never got a cent for my time on the boat, and I do not think I earned any beyond the food I ate. The next year I shipped on a sailing craft, which I liked to a passion; but the John Brown raid had created such excitement that I was obliged to leave my vessel in Annapolis, Maryland, and take passage north on a vessel that had been cleared from a point in the south. I made many efforts to secure protection as a sailor but failed.

Page xi

Then there came into our community Rev. Joseph H. Smith, a man who knew how to interest boys: who was full of life, but an earnest, whole-souled gospel preacher. He had a rich voice, and knew how to use it; preached always with his eyes apparently shut, but never got lost in his sermons. Under his preaching, as he portrayed the love of God, I was deeply convicted; I was also reading "Baxter's Saints' Rest." The clear light of pardon and acceptance came to me on a bright moonlight night as I was coming home from the meeting, walking with my oldest sister. I knew then, and I know now, that God owned me as His child. Praise His name!

It was probably the next day, certainly soon thereafter, before I had got adjusted to my new life, that a fellow perhaps not knowing of my conversion, rushed into me for something of the bygones, and I found myself engaged in a fight. I had not learned the "other cheek" lesson. When I came to myself I was chagrined, sorry, and in spiritual darkness. I thought I had forfeited my right and should give up at once. My mother saved me from a breakdown here. She was wise and good and while impressing upon me the wrongfulness of my act, gave me encouragement to go to God for forgiveness, and hold on to my profession. I was saved. An unwise counsellor might have driven me away.

Page xii

Not long after this came the distinct and clear call to the gospel ministry. I hesitated; but it finally came to be to me a question of personal salvation. I must preach or become a cast-away. In informed my class-leader, Mr. Abijah Gould, who asked me if I had fully counted the cost, and did I remember that, to use his own words, "the finger of scorn would be pointed at me." I assured him I had made up my mind fully, and was ready to accept whatever might follow. License came, and in 1864 I was ushered into the ministry to begin the story I have just finished. Great have been the mercies of the Lord to me. From the plateau to which I have arrived, I can not only look backward and downward, but I can look forward and upward. What do I see in that upper region toward which I mount? In the sweet and inspiring language of the older and deeper hymnologists I can read:

"I see a world of spirits bright,

Who taste the glories there,

They all are robed in spotless white,

And conquering crowns they wear."

And among them are some whose lives on earth were closely woven in with mine; and their white robes are beckoning me from the heavenly sphere. Only a little while, dear ones, and I too will fly from the mount below to the bending heights above.

Page xiii

INTRODUCTION

Dr. T. G. Steward has been a voluminous producer of potential literature. His works include pamphlets, and substantial books on theology and history. The book presented here is probably his last and crowning work. It is biographical, covering a most interesting period in the history of the country and the church--the fifty years from 1864 to 1914.

The reader will find here, revolving about the writer's own career which is portrayed, intimate glimpses of the religious, social and political history of the times. The fifty years' service of our author have not been bounded by the pulpit, the rostrum and library. As a chaplain in the the United States Army he has seen service in tent, in barracks and in the field. Haiti to the south of us, and the Philippines on the border of the Orient are far flung outposts in which our author has served with distinction and honor.

Dr. Steward will long be a marked figure among us. Since his retirement from the Army, he is one of the few men among us having the leisure together with the culture and ability to lead a literary life. An appreciation of Dr. Steward, written several years ago by that careful observer and

Page xiv

judicious chronicler, Mr. John Wesley Cromwell, lately honored by Howard University with the degree of Doctor of Laws in recognition of his valuable history and literary labors, will show better than any words of mine how our author was regarded at close range when he was at the zenith of activities in church life. Dr. Cromwell says:

"The career of Rev. Theophilus G. Steward, D.D., as an evangelical preacher closed by his appointment as Chaplain to the 25th U. S. Regiment stationed at Fort Missoula, Montana. Dr. Steward certainly has no superior as a pulpit orator in the A. M. E. Church. Of him the words of Rev. J. C. Embry to me, that he can say what he wants to say better than any other preacher in the A. M. E. Church, will certainly be indorsed by all who have listened to his administrations of the Word during his pastorate of the Metropolitan A. M. E. Church, Washington, D. C. Never seemed a pastor better adapted to the great needs of a people than he. Cultured, genial, pious, eloquent, he continued to attract to the church people who never believed it was possible they could see anything good, anything elevating, in the Methodist Church.

"By his personal example he won many a soul to an open profession in the belief of a risen Saviour. When the relations of the church and himself were severed in 1888, there were many sad hearts. An experience of three years has shown

Page xv

that he is the best man yet developed for the place. Without going any further into much that has no legitimate place here and now, suffice it, that 1891 found Dr. Steward in charge of a church at Baltimore with his family here where they were located for the increased educational opportunities afforded. Then it was that he was induced to make a formal application for a U. S. Chaplaincy. In this he had the support of Hon. B. K. Bruce and Hon. John R. Lynch, with that of P. M. G. John Wanamaker, who had known him in Philadelphia.

"Ten years have elapsed. Dr. T. G. Steward is once more here. He is now on leave from his regiment stationed in the Philippine Islands now in possession of the United States as an outcome of the war with Spain. Since he was appointed Chaplain he has been a widower and is now remarried. This time the occasion of his visit to Washington is an engagement to lecture on the Philippines in the Metropolitan A. M. E. Church, Sunday, September 8, 1901, he preached from his pulpit by invitation of the pastor, Rev. D. G. Hill, and the courtesy of former Chaplain (War of the Rebellion) Wm. H. Hunter, the presiding elder, whose service it was. The congregation was an unusually large one. Douglas was not there, neither was Bruce nor Langston, these having all gone to the silent land. One half a generation has passed since he was appointed there as pastor in

Page xvi

1886, yet there were many brought to the church during his pastorate and who worshipped there regularly, to welcome him and his message.

"It was a service of great spiritual uplift; to those who heard Dr. Steward for the first time it was a revelation of his great oratorical and spiritual power. Prof. Layton gave a solo and after the service hundreds pressed forward to greet their former pastor by the hand. Monday night the Chaplain was entertained by a dinner at Murray's Cafe. Twenty sat down to one of the finest dinners in his honor. Such men as Judge Terrell, R. S. Smith, L. M. Hershaw and Eugene Brooks were among them. It was the first time that Chaplain Steward had been thus honored and he appreciated the occasion accordingly. It was nearly twelve when the party separated with so many pleasant remembrances and with so much instruction and enlightenment on conditions in the Philippines.

"At the lecture on the subsequent night nearly three hundred persons were present. As chairman of the committee of arrangements I presided and introduced the lecturer, Bishop Jas. T. Holly being in the audience made the invocation."

Biography is the richest form of history. It presents an intimate picture of the life and times which it treats. Frederick Dogulass and the late Booker T. Washington have each given us biographies

Page xvii

which are of consuming interest, and will ever remain among the most treasured productions of the period of American history which they represent. But here is something different. Here we have an American of African descent who is not struggling "Up from Slavery," but a Christian scholar who met the freedmen on the very threshold of their emancipation, and who since with singleness of devotion has been guiding them and their descendants in the paths of knowledge, character and virtue.

For many years the African Methodist Episcopal Church has had an official historian. But here is something spontaneous and unique. Dr. Steward's painstaking thoroughness, together with his learning and experience, sufficiently guarantee the value and reliability of the contents of this book. We count it an honor to have the pleasure of commending and speeding on its way this book which is in itself a rich treasure garnered from fifty years of the faithful life of Theophilus Gould Steward.

REVERDY C. RANSOM,

Editor A. M. E. Review.

Page 19

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL CONFERENCE OF 1864: Bishop Quinn, Payne and Nezrey. Captain Robert Small; Chaplain H. M. Turner; Rev. James Lynch. Bishops Campbell and Wawman elected; Annual Conference in Salem, N. J. Bishop Wayman preaches; Rev. W. H. W. Winder faints in pulpit; Rev. A. L. Stanford preaches; My first appointment; First visit to New York; Sail to Charleston, S. C.; Organization of South Carolina Conference, Revs. James A. Handy; J.H.A. Johnson, etc. Orgaization of church in Beaufort; First sermon.

In May, 1864, civil war was still raging in our land, although the Confederacy was then approaching its collapse, emancipation had taken place and the ex-slaves were crowding into the Union army. It was at this eventful time that the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church met in Philadelphia, assembling in old Bethel Church, on the ground where Allen preached, and where the denomination had its birth. The body was composed of all the traveling elders of the connection of six years standing and over, and of certain local preachers who were admitted in the sense of lay delegates. Rev. Alexander W. Wayman was chief secretary, and the sessions were presided over by Bishops Payne, Nazrey and Quinn alternately. It was a very earnest, orderly and in every way, respectable body of men.

The chief speakers on the floor were Revs.

Page 20

Charles Burch, W. A. Dove, W. R. Revels, Enos MacIntosh, Elisha Weaver, J. M. Brown, and others, principally from the West. Rev. M. M. Clark, and an Indian minister by the name of Sunrise were conspicuous figures, as were also Rev. James Lynch and Chaplain H. M. Turner. Captain Robert Smalls of "Planter" fame visited this conference. (See note.)

Perhaps the most impressive session, aside from that of the ordination service, was that held with respect to the memory of Dr. J. J. Gould Bias who had died not long before. Bishop Payne on that occasion delivered an elaborate and very carefully prepared address in which he emphasized especially Dr. Bias' important work in the cause of popular education and temperance.

As this was the first conference of ministers that I had ever witnessed, and as I then was in the course of preparation to enter the regular ministry, or according to the phrase then in use, was preparing to "join the itinerancy," it was but natural that I should receive lasting impressions of both the subjects discussed and the speakers who took part in the discussion. I can, therefore, remember the speeches made both by Elisha Weaver and J. M. Brown on the subject of divorce and re-marriage; and also much of the discussion relating to the union of the two African Methodist Churches. I attended the convention held by the

Page 21

representatives of these two bodies and was not favorably impressed at the time. I felt that there was mutual distrust and that each side was seeking to test the other. Rev. R. H. Cain appeared to be the leading mind among our men.

After the adjournment of this conference, the Philadelphia Annual Conference met in Salem, N. J. Bishops Wayman and Campbell who had been ordained in the General Conference of Philadelphia met this conference, although Bishop Nazrey appeared to be in actual charge. At the close of the conference Bishop Nazrey took formal leave and departed to his work in Canada. Bishop Wayman preached a very impressive sermon from the text, "They shall hunger no more" (Rev. 7:16-17). This was the first time I had heard him and I was charmed with his rich voice, his beautiful imagery, and his calm and effective delivery. Rev. A. L. Stanford preached a powerful sermon on "Angelic Agency," taking for his text, "The angel of the Lord encampeth round about them that fear him and delivereth them" (Psa. 34:7). I was sitting near a white minister while Stanford was preaching, and as we were well back in the congregation, I noticed that this minister was pretending not to be giving any attention to the sermon, but was using his pen-knife on his finger nails. A degree of contempt for the pitiable fellow arose in my heart, which I made haste to stifle, that I

Page 22

might enjoy the speaker's masterly discourse. Here also Rev. W. H. W. Winder attempted to preach after having gone through the ordeal of examination for elder's orders, and fainted in the pulpit. Bishop Campbell came to the rescue at once and held the attention of the congregation tion.

It was at this conference, on June 4, 1864, that I was admitted to the traveling connection on probation. The committee examining me were: on Doctrine, Rev. Peter Gardner; on Discipline, Rev. W. D. W. Schureman; on English and general information, Rev. A. L. Stanford. Each of these ministers was an expert on the subject he took in hand, and the examination was genuine. The beginning of my ministry is coincident with the date of this conference.

On joining the conference I expressed a desire to go South, but it was not thought best at that time, and I was appointed to a little church in South Camden, called Macedonia. Many years afterward I met a man who had been a class leader in middle age at the time of my pastorate there, and remarked to him that I had at one time been his pastor. He could not recollect me at all. After much explanation he finally called up my ministry by remarking, "O, I do remember; conference sent us a boy one year; are you that boy?"

On entering Conference, June 1864

Page 23

It was not unpleasant for me to acknowledge the fact.

At my first quarterly meeting here, my pulpit was supplied by Rev. Elisha Weaver, Bishop Campbell and Rev. W. D. W. Schureman and the ferry boats leaving South Street, Philadelphia, were filled to their capacity with colored people coming over to my meeting. The church was packed and all the open spaces around the church, so eager were the people to hear these great preachers. During the day Mrs. Stidum, a member of our church living in a building near by, received word that her husband, a soldier, had been killed in battle, and her cries of sorrow were heard mingling with the joyous shouts of the people made glad by the gospel.

Rev. W. D. W. Schureman preached at night as no other man could preach, from the text, "And a man shall be as a hiding place from the wind and a covert from the tempest; as rivers of water in a dry place as the shadow of a great rock in a weary land" (Isa. 32:2). He was a man of fine appearance, well proportioned, graceful and impressive in manner, with a clear flexible and penetrating voice, and wonderfully skilled in elocution. But underneath all was his fine spiritual nature, rich imagination and capacity for sympathy with men, which God used in this servant to the pulling down of the strongholds of the devil. As a preacher,

Page 24

and in the administration of discipline as church governor, he was eminently successful. In his private and domestic life he was not happy, and as a pastor he was not satisfactory, yet because of his great powers as a preacher all the churches desired him. On this occasion his accustomed eloquence carried the people beyond themselves, and my quarterly meeting was a high day, indeed. Thus the older preachers helped the "boys" in that day. I remember also the kindly help of the Rev. J. B. Reeves, the ablest of the Presbyterian preachers, who came over from Philadelphila and preached for me from the text, "Oh, that I had wings as a dove," etc.

Rev. William Moore, who had special oversight of my work, and who was a forceful and earnest preacher, stern for the right and stern against the wrong, but tender and loving toward men who were willing to hear the word of God, like a true father in Israel, guided and defended me during my ministerial infancy. In my revival efforts he was mighty; his words were as nails fastened by the Master of assemblies, as he rehearsed the sins of men from the text, "Against thee, thee only have I sinned," or "How shall we escape if we neglect so great salvation?" These great preachers of a past generation! May their sons in the Gospel rise up and call them blessed!

Page 25

*I served in this church with more or less success until the first of May, 1865, not completing a full conference year.

*When I began my work in Camden in 1864, I laid out the following daily program: From 7 to 9 A. M., Ancient History; from 9 to 10, Thelogy; from 10 to 11, Homiletics; from 11 to 12, Fletcher's Appeal, etc.; from 3 to 4, Composition; from 4 to 5, Reading. This was a very unwise schedule and it was as impossible as unwise. No one but a "boy" unschooled could have conceived a day of seven hours or more spent in books.

On April 30, 1865, in the evening, I received a note from Bishop Payne to meet him in New York, prepared to embark for Charleston, S. C.; and by 8 o'clock next morning I was on the train, on my way to that city. I arrived there about noon on the first day of May; and the first day of May at that period was the greatest day of the year in New York City. It was "moving day"--the day of general change of domicile. This was the occasion of my first visit to that city, and I was bewildered with what I saw. The streets were crowded with furniture cars, and other vehicles; it was raining violently; anger, greed, and distress were everywhere visible; in a language which

*On August 7, 1921, I visited Macedonia Church, the Rev. R. B. Smith being pastor at that time, and there met Mrs. Mary Laws, a hale, happy looking elderly lady, who informed me that she joined the church under me in 1864, being at that time twelve years of age. Her name at that time was Mary Painter. She had been a member 57 years.

Page 26

sounded decidedly foreign to me, I could distinguish amid the harsh yelling, oaths and cursing in strains more vehement than I had ever heard before.

With an Irish hackman for pilot and driver, I succeeded in finding the Bishop and lodgings. I remained in New York until May 9th, during which time I visited Greenwood Cemetery, Barnum's Museum, and every other place of public interest that I could reach. In the meantime Rev. James A. Handy and Rev. James H. A. Johnson from the Baltimore Conference had joined our company. Of the latter I can say that I heard him preach for the first time while we were here in New York. It was in Bethel Church on Sullivan Street, and while he was reading his sermon, a sudden current of air swept over the pulpit and carried away some of the loose pages of his manuscript, leaving him in a hiatus, until a kind brother picked up his scattered leaves and replaced them before him, thus relieving his embarrassment.

On May 9th, about 10 A. M., after much negotiation, Bishop Payne, Brothers Handy, Johnson and myself were permitted to go on board the fine government transport "Arago," bound for Hilton Head, S. C., then the headquarters of the department of the South. By twelve we were steaming out of the harbor. The wind was west; it was raining gently; and the sea was comparatively

Page 27

smooth; but as we were all, except Bishop Payne, most thorough landsmen, we soon began to feel the effect of the ship's motion. *For myself, all I can say is, I was sick, very sick, extremely sick, sick from head to foot, all over sick, completely down and out, willing to become anything or nothing. It was not pain; but, Oh, such nausea, a sickness unknown on land, a sickness that no one inexperienced can understand; it was sea-sickness.

*Not being used to any such experience, it is now admitted that I was right down scared and considerably agitated. I started out sick, and was sick from Tuesday to Thursday; but was encouraged by a knowledge of the fact that we were on a mission for the Lord. I was not able to eat more than two meals in three days; and as twelve dollars had to be paid for three days in advance, those two meals cost me six dollars a piece, and have been tasting like green backs ever since--Quarto-Centennial address of J. H. A. Johnson, delivered in Charleston, May 16, 1890.

I have had it many times since, but never like that first time. Old Neptune demanded his initiation fee, and he got it--dinner, dumplings and desert. This initiatory ordeal lasted about thirty-six hours, after which we were let off as seamen on probation. We passed Hatteras and our mercury climbed to 76, and on the 12th, three days from New York, an awning had to be spread to protect us from the sun.

The Honorable Benjamin Brewster was a passenger on this trip, and the conversation carried on by him and Bishop Payne to which the rest of our company were merely listeners, was a great source of enjoyment and profit. We arrived at Hilton

Page 28

Head, about sixty miles from our destination, and were within the military department of the South, commanded at that time by Major-General Q. A. Gilmore.

We remained at Hilton Head until about 10 o'clock that night, observing while there the numerous government buildings and hotels, and especially the little Freedmen's village named in honor of the astronomer-general, Mitchel, who early gave his life in the cause of the Union. Mitchellville then contained about 1500 inhabitants, and three churches, in which public schools were taught by "Yankee Teachers." Numerous officers appeared to be strutting around in new uniforms; ladies were riding along the beach on horse-back or in ambulances: Hilton Head, though formerly a rebel stronghold, was experiencing on every hand the tread of the "Yankee" foot.

At ten o'clock P. M. we took the little steamer "W. W. Coit" for Charleston; the moon was shining brightly, the wind was slight, yet the sea was quite rough; but we slept. At five o'clock in the morning we were on deck to view the harbor scenery. Fortunately I made the acquaintance of a gentleman on board, Moore by name, a native of Charleston, familiar with all the features of the harbor. By him I was shown Sullivan's Island, Fort Sumter, and every other place of interest within sight, until the "Battery" came into view.

Page 29

This so captivated my guide that he forgot all else. The "Battery," or front park of Charleston, is the pride of every resident of that city, and well deserves to be, presenting as it does to the visitor coming by sea a scene of rare picturesqueness and harmony.

We arrived in Charleston at about 7 A. M., landing at what was then called Accommodation Wharf; and were conducted to the house of Mrs. Williams, a Methodist lady living at that time in Laurel Street. Later Mrs. Williams became the wife of Rev. Richard Vanderhost, a very eloquent preacher in our denomination, who afterward became one of the first two Bishops of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. On our way to this residence we passed through Broad, Meeting and King Streets; and there saw the havoc of war. Houses on every hand had been perforated by huge shot and shell from Gilmore's fleet; great fires had swept through the city leaving a vast army of sullen-looking, solitary chimneys; business was generally suspended; grass was growing in the streets; the greater part of the population had fled; and only the beating of drums, the clattering of military horsemen, and the continual promenading of the "boys in blue," many of whom were black boys, relieved the general monotony that prevailed. War, war, what a scourge is war! Man arises to be his own whip-master, and terrible

Page 30

are the blows he inflicts upon himself. Let us hope that the fearful castigations he gives himself from time to time may ultimately result in his enlightenment and correction.

It was Saturday when we landed, and having arrived at our lodgings, returned thanks to our Kind Preserver, and breakfasted, we organized informally to make preparation for the ensuing Sabbath, and then devoted the day generally to quietness and rest.

Sunday morning I preached in what was called *"Old Bethel,"

*The church contained nothing remarkable, except its pulpit. This was very high, cramped, and over it was suspended a kind of sounding board appearing like a huge bell without a clapper, reminding one constantly of a deadfall intended to entrap the preacher. Underneath this apparent man-trap, with a lively sense of insecurity I attempted to preach.--My Diary.

a little frame church situated on Calhoun Street near Pitt Street. Incidentally I noticed that all the women of middle or advanced age wore beautiful turbans instead of bonnets; and that the young ladies universally sported broad-rimmed hats. I noted also, the generally soft expression upon all female faces. Very little gaudiness was visible except in the matter of jewelry, which many wore to excess. The feather fan was in the hand of almost every woman. Following me, Rev. C. L. Bradwell of Savannah delivered a brief exhortation, giving evidence of a good mind and of fine feelings. In the afternoon

Page 31

I preached in St. James Church, corner of Spring and Comings Streets. At four o'clock Bishop Payne preached to an enormous congregation in Zion Presbyterian Church.

On Monday morning, May 15, 1865, the first conference held by our church within the territory of the South Atlantic and Gulf States began its sessions in the Zion Presbyterian Church in Charleston, S. C., Bishop Payne presiding. The great building was crowded with spectators, and there was much more in the way of explanations, preaching, singing and prayer, than of business. The sessions continued from the 15th to the 22nd, a full week. During the session, Major Martin R. Delaney delivered a very important lecture on the "Unity of the Races," bringing into view the teachings of anthropology up to that date, and sustaining his own position with abundant forceful argument. Brother J. H. A. Johnson and myself were ordained deacons and elders during this conference, so great was the emergency. We were ordained in Trinity Methodist Church, the property of the M. E. Church, South. At that time all of the churches were in the hands of the military authorities. Our conference at its close numbered twelve members, classified as follows: elders, six: Deacons, four; Licentiates, two; the old apostolic number. The elders actually present were: James A. Handy, James H. A. Johnson, James Lynch

Page 32

and myself; but R. H. Cain and A. L. Stanford arrived soon after the adjournment of the conference and took up the work assigned them, the former at Charleston, the latter at Savannah.

In this conference, which met in Charleston May 16, 1865, beside the men who came from the North, and whose names have been given in the preceeding pages, there were present from the cities of Charleston and Savannah the following brethren: Charles L. Bradwell, William Bently, James Hill, Gloucester Taylor, Robert M. Taylor, Richard Vanderhost and John Graham. These were all leaders or exhorters, or, in case of one at least, local preachers; and were of much experience, character and talent, having been recognized as such by the ministry of the church to which they belonged. Charles L. Bradwell, however, was the only one among them who was prepared at that time to leave all and enter upon the work of the ministry, although he was then a prosperous mechanic with a business of his own.

I have a very distinct recollection of *John Graham,

*He was a Christian spiritual giant of many cubits, leading a mighty host of Christian followers in and out of this grand old city by the sea. In physique he was well proportioned; in moral courage and Christian fortitude, he was a fac-simile of St. Paul; in natural ability and far sightedness into future developments as the result of well laid plans, he had few equals and certainly no superiors; in acquired literary attainments he ranked generally with the men of his day. This grand old man and Christian hero, at the time he entered the ministry of the A. M. E. Church, had passed his meridian of life in the flesh by twenty-two years, yet his spiritual life was just at its zenith, hence of all the galaxy of men who began this glorious church work in those days, the brightest among them was John Graham.--Address of J. E. Hayne, Quarto-Centennial. Charleston, May, 1890.

who was the class leader of the lady whom I married while in Charleston. He was

Page 33

then about sixty years of age; a very sincere, earnest, intelligent and devout Christian man. He had served many years as class leader in Bethel Church, and as such was a very honored leader of the Sunday morning prayer meetings. Rev. Charles L. Bradwell was received on probation, as were also Gloucester Taylor, Robert M. Taylor and Cornelius Murphy; but these latter three did not take work. William Bently and James Hill were ordained deacons and were left to work in a local capacity in and around Savannah, to meet the appalling need of the thousands of freedmen who were in that vicinity, devoid of the services of a Christian ministry.

This whole section, with its hundreds of thousands of men, women and children just broken forth from slavery, was, so far as these were concerned, lying under an almost absolute physical and moral interdict. There was no one to baptize their children, to perform marriage, or to bury the dead. A ministry had to be created at once--and created out of the material at hand. The courage of the leaders of our church is to be commended in that, in the face of the great crying need, so

Page 34

apparent to all, they dared to lay hands on men, not fearing the criticism of those who openly proclaimed in Charleston in 1865 that the A. M. E. Church had "neither the men nor the money" to carry on work in the South. These critics forgot that God could call the men; and that the A. M. E. Church had the authority to commission them when thus called. To the six ordained men brought on the ground from the North, the church added by ordination in 1865 five more, including the Rev. William Gaines who was ordained by Bishop Payne by authority of the conference, at Hilton Head after conference had adjourned.

Later there came into the field from the North, Rev. George. W. Brodie and Rev. Charles H. Pearce from Canada, and Rev. George A. Rue. Rev. George A. Rue was assigned to Newberne, N. C., and Rev. George W. Brodie to Raleigh, N. C. North Carolina was thus pretty well manned: Handy at Wilmington, Brodie at Raleigh, Rue at Newberne, all experienced, able and efficient ministers. Pearce had been assigned to Tallahassee, Fla., where he found such worthy assistants as William G. Stewart, the one-armed preacher; and T. M. Long, the ex-soldier, a strong organizer and a man of extraordinary sagacity and sound judgment.

But to return to the personal narrative. On Thursday, May 28, 1865, in company with Bishop

Page 35

Payne, Brothers Lynch, Handy and Johnson, I secured passage on the little steamer "Loyalist" for Hilton Head. The weather was threatening, but the captain decided to take the outside passage although it is possible for steamers of the size of our vessel to make the trip from Charleston to Hilton Head and even to Savannah without risking the perils of the sea. The British Colonel Maitland made use of these inland waters in conveying his troops from Beaufort to Savannah in 1779, guided by some Negro fishermen, and thus prevented the French and American forces from capturing that city. Before embarking I had eaten a quantity of South Carolina peanuts, as of course, there was nothing in the way of food to be had on the boat; indeed accommodations on the boat were as bad as they could be. We left Charleston at four o'clock in the afternoon, the wind was from the southeast and blowing strongly. Later it increased in violence, accompanied with thunder and lightning. It was my first experience with a storm at sea, and the awful grandeur of the scene affected me greatly. Our little boat was tossed by the waves as a thing without significance. When off Stono Inlet an effort was made to change our course so as to enter the inlet, and the boat which had been until then kept head to the sea, was swung around sufficiently for the sea to strike her on the side of the bow; the rolling was fearful;

Page 36

all loose stuff was thrown overboard by the violent pitching of the vessel; passengers became alarmed and the cry started, "She is going down." I awoke Bishop Payne who was until then asleep, and told him of the horrors of the situation. I said to him, "Bishop, it is reported the vessel is going down." He lifted his head and said, "Nothing but the power of the Almighty can save us," and calmly lay down again, his action corresponding exactly to the prodigious sublimity of the occasion and filling me with admiration and wonder. Our vessel, leaking badly, coal running low, was compelled to keep head to the storm until about 11 A. M., when it pleased the Almighty to cause the wind to shift, accompanied by a heavy downpour of rain, which served to beat down the sea, and by three o'clock we were entering the roadstead at Hilton Head. Anxiety for our safety had become so great that another boat had been despatched from the Head to search for us. I said I had eaten a quantity of peanuts before embarking, but during the storm these had all come up de profundis and gone to feed the fishes.

Here at Hilton Head the pious and accomplished *James H. A. Johnson

*Rev. J. H. A. Johnson, than whom a man more devoted to truth never lived, recounts the experiences of that night as follows: "When they got to the pier they found nothing but a little nisignificant propeller called The Loyalist, that was not suitable for either river or sea. And then the wind was blowing a perfect gale, but aboard this frail craft we had to go; and so Bishop Payne, Lynch, Handy, Steward and I passed down the gangway on to the contracted deck. There we awaited the signal for the casting loose of hawsers; after some delay it was given and we moved out toward the Atlantic. The trip we were to make required only seven or eight hours, but as we progressed and night came on the glooming gale turned into a raging storm. The wind howled. With the down pouring rain and billows rolling high, it was a fearful storm. In that frail craft, groaning and creaking, careening, and trembling, beaten about by that angry sea, surging sea, we were from evening until morning and until every heart had given up in despair. I said to Bishop Payne while he was lying upon some freight, "Bishop, do you think there is any danger?" He calmly replied, "Nothing but God can save us." We all then silently prayed and waited for results. We should have been to the landing about 11 o'clock on Thursdays night, but Friday morning, May 26th, dawned and found us still being tossed about in that raging storm; and we continued to be until the morning was pretty well spent. Finally an abate ment came and we were able to make headway towards land. As we were doing so a steamer hove in sight and we found it to be one that had left Hilton Head to see what had become of us. Without her assistance The Loyalist made port at 3 o'clock on Friday afternoon. When we landed we felt as though we had escaped from the jaws of death, and that God himself had saved us." The reader will note the apparent discrepencies in these accounts as to calling Bishop Payne. We were together, Johnson and I, and each so excited as not to note what the other did. I reported the rumor that the boat was going down, I am sure; and Brother Johnson is just as sure that he asked as to danger; and the reply of the Bishop came to us both.

was to begin his labors. He

Page 37

was a man of most engaging manners, artistic tastes, and scrupulous correctness in language, dress and deportment. As a writer he was very painstaking and explicit, leaving nothing for the reader to be in doubt of as to the meaning intended. As a speaker he was very deliberate and emphatic. As a preacher, soundly orthodox and evangelical. A psychometrist who had never seen him, and had no other knowledge of him save what he obtained through occult means gave, in my presence, the following reading: "He is a person of decided character. He formed his opinions quite early in life and it is hard for him to adopt new views. One would take him to be a little too positive to hear him talk; and yet he is willing to weight the arguments of those who hold opposite views and to weigh the subject. He does not, however, give up his own notions until he has the most indubitable proof to the contrary. When he

Page 38

does change his views, he will be equally as positive in his new position. He acts from principle in every move he makes. His phrenological character is conscientiousness, firmness, hope; the intellectual faculties are well developed. His reverence is more for principles than for persons. I should think him qualified for a minister of the gospel. His intellectual attainments qualify him to fill any position requiring brain work, mercantile or educational. He would be well qualified to fill the editorial chair--well qualified. He is very self-balanced, has perfect control over himself. I should take him to be about five feet eight inches in height; light complexion; a great deal of expression in his eyes. His countenance is quite expressive, especially when interested in conversation; not very heavy nor very light-built--about

Page 39

medium; his weight might be 145 pounds, perhaps a little more; he takes hold of any work as if he meant to accomplish something. There is a great deal of energy in him. His tastes are intellectual." I have quoted this reading in full not only as a matter of curiosity (as the man who gave it was aged and blind), but also because it gives a most accurate description of the man whom I count among the best of men I have met, and who was to me a friend in whom my soul confidently trusted--a cultivated Christian gentleman.

From Hilton Head I proceeded to Beaufort, about 16 miles distant from the "Head" (as we soon learned to call the headquarter post), situated on Beaufort River, landing there Saturday, May 27, 1865. Here, inexperienced, unaccustomed to the climate, and entirely unprepared to cope with the topsy-turvey conditions I met, I began my work. *

* It was thought that the American Missionary Association would assume a part of the support of the missionaries whom Bishop Payne took with him from New York. The following letter received by me acknowledging receipt of my report, confirms this view; but for myself, I can say that I never received any support from that association. New York, July 25, 1865.

Rev. T. G. Steward, Beaufort, S. C.

Dear Brother:

Yours is received. We thank you for promptly filling and returning our circular. You are right in the part we assume in your support. We shall remember you with great interest as we see you toiling for the spiritual good of those whom we hope will gladly receive the Word of life at your hands, and be made rich with imperishable riches. A glorious mission is yours. May God grant you grace to fill it, so as to honor the Master.

We hope you will remain in health of body and mind. We shall ever be glad to hear from you.

Yours very truly,

GEO. WHIPPLE,

Cor. Sec. A. M. A.

I began at the beginning; by securing board temporarily with a Mrs. Bram who kept a kind of officers' mess where were boarding Major Augusta,

Page 40

chief surgeon of one of the colored regiments, and who was in fact the first colored man to put on officers' uniform in the Union Army during the civil war and from whose shoulders ruffians tore the straps in Baltimore; Captain O. S. B. Wall, and a number of colored civilians. I did not remain in this public house long, but soon after found board with a lady named Cruz from Palatka, Fla. She and her daughter kept a very pleasant home and here I and Major Martin R. Delaney boarded. I visited the sick and buried the dead, and finally got together and organized a church. A brother had been preaching there before, under the supervision of our missionary, Rev. James Lynch, but the church had not been organized. Hence I did not begin my formal work as pastor of a mission church until June 18, 1865.

It is probable that I had heard of Bishop Wayman's popular sermon on the text, "I seek my brethren," which he had preached in so many places directly after the war, although I had never heard

Page 41

the sermon nor seen any notes of it in print. But recognizing that the Bible is a free book for all preachers, and that no man can take out a patent right on any particular passage of God's book, I determined to employ the same text. Accordingly my first sermon in Beaufort was from the text, "I seek my brethren." I have preserved these notes and now present them to the reader with the explanation, that I did not then, and do not now, preach from manuscript; nor do I memorize my discourses. Thus it is not at all probable that I used the exact words as written. My custom has been during my half century of preaching, to work out all of my ideas, writing them out in the order in which I intend to present them, and trust to the occasion for the language. In my earlier days in writing my sermons, the following passage from one of my brother's poems often gave me stimulus:

"A ship at anchor in the distance shows

By the wan gleam of starlight, and the crew,

Pull a small boat towards the breaking shore,

Where none but madmen dare to risk their lives;

But at the heldm, a swearing steersman sits,

Who knows the path--has traversed it before."

I have always felt that the preacher should know the path over which he pilots his thoughts, and

Page 42

know it because he has traversed it before

Inaugural Sermon, Beaufort, S. C., June 18, 1865

Text--"I seek my brethren" (Gen. 37:10.

Jacob, the patriarch, sometimes called Israel, had twelve sons. Next to the youngest was Joseph, who was very much beloved by his father and others; and several dreams that he had showed that God loved him also, and that He had raised him up for a special purpose. One night Joseph dreamed that he and his brothers were all binding wheat in the fields, and it came to pass when he had bound a sheaf and stood it up, that the sheaves that his brothers had bound all fell down before his sheaf. He told this dream in the presence of his brothers and his father and mother. His brothers became jealous of him and hated him.

A few days thereafter the older boys took the flocks of sheep and cattle several miles away from home to pasture and staid by them to watch them night and day for several days. Now after they had been gone some time, a fortnight perhaps, the father wanted to know how they were getting along--if they were well, if the flocks were all right; so he called Joseph who was a little lad of a boy, saying, "Joseph!"

The lad answered, "Here am I."

"I will send you to see how are thy brethren.

Page 43

Go, I pray thee, see whether it be well with thy brethren and well with the flocks and bring me word again."

So the little fellow started out and went to the place where he had heard his brothers were keeping their flocks; but when he got there, he could not find either his brothers or the flocks. He, as any other sensible boy would do, commenced wandering in search of them. While thus doing a man met him and asked him what he was looking for; and he answered in the words of our text, "I seek my brethren."

As this is the first time I have ever had the privilege to meet you, I have thought I could not better tell you my business than to quote this language of Joseph and claim it as my own--I seek my brethren. I come from New Jersey to South Carolina in search of, or hunting for, my brethren. First let me give you the object sought, or tell you who are my brethren.

1. Those whom Joseph sought as his brethren were all the sons of one father, but of different mothers. For instance, there were Reuben, Simeon, Levi and Judah born unto Jacob by his first wife, Leah; then there were Dan and Naphtali, sons of Rachel's maid, Bilpah; and Gad and Asher born of Leah's maid, Zilpah; but these Joseph calls brethren because all of one father. With this same feeling have we come here to

Page 44

preach the Gospel--to find our brethren. And in one sense we look upon all men as our brethren; for, though they may be born of different mothers, that is, may belong to different races and nations, yet they are of one Father who is the source of all life; and who of one blood has made all nations to dwell upon the face of the earth; and like Jacob acknowledges them all his sons. We, therefore, like Joseph, acknowledge them all as brethren. All mankind is the object of our search.

2. But more expressly have we come to seek those who are our brethren by virtue of race; not because we care anything for races or nations, but because they have been and are yet in a great measure our brethren in affliction. And that very affliction has served to bind us together by the two-fold cord--sympathy, for the oppressed, and love of man. Our fathers have passed through the fiery furnace of slavery and escaped to the North, where a nominal or partial freedom reigns; they have taught us in infancy to remember those in bonds as being bound with them; and from our churches, our firesides and our closets have gone up the petition: "Oh Lord, remember those that are bound down under hard task masters, our brethren in affliction! Break every yoke, snap in sunder every chain, and let the oppressed go free!"

God has heard; Glory to His name! Answered the prayers of His people, and so to speak, has

Page 45

come down to deliver them. The yoke is cast off, the chains are broken and we come in search of our brethren, the Freedmen.

3. We come to seek those who are our brethren by adoption--those who have drunk the wormwood and the gall of conviction of sin, and who have at last heard the welcome words of Jesus saying unto them, "Thy sins beforgiven thee. Arise, shine for thy light has come and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee." Those who have passed from death unto life and know that their Redeemer lives; who can appeal to high heaven to witness their acceptance with God; who can say, "My witness is in heaven; my record is on high." All who can say "Abba--Father--the Holy Ghost," bearing witness with their conscience that they are the adopted and heaven-born sons of the Most High. We are seeking them.

4. Lastly, we seek those that love our church government best. I mean Methodists. Not that we would be supposed to have the least taint of prejudice to any evangelical denomination or church--God forbid! But as there are Baptist, Presbyterian, and other missionaries here on the ground to look after those who are accustomed to their respective modes of worship and church government, we feel our mission with regard to Christians, to be directed to those who are or have been Methodists. We come as brother Methodists

Page 46

to seek our brother Methodists.

II. How do we seek them.

1. I think from reading this story of Joseph seeking his brethren and also from experience in country manners and customs that Joseph, when he did not find his brethren where he expected to, looked anxiously for some track or traces of the flock that he might learn the direction they had taken; and this "seeking" in all probability gave rise to the question, "Whom seekest thou?" We look first for the track of man, for his house, his fields, his churches, that we may find our brethren. We desire to find men of whatever class they may be; if they are of European, African or Asiatic mothers, we do not care; they are our Father's children.

2. We look for the traces of that afflicted people, the people who were as the Apostle says, "Killed all the day long;" we look for the cotton fields which they cultivated; the rice swamps they watered and watched; the little huts wherein they dwelt; the blood-hounds that chased them; the swamps in which they, terrified and exhausted, took refuge. We find all these; but still we seek our brethren. At last the welcome sight is obtained. From every direction I see them coming. Thank God! The nation, scattered and peeled, is coming stretching out its hands unto God. They are our brethren!--hair, skin and eyes say so.

Page 47

3. But how do we seek these our brethren in Christ? We look for the marks; we see great church edifices and are told they are often built almost entirely by the African or colored children, or sons of God by adoption. We see their mark as among the multitude we listen to their songs of praise and their fervent prayers to Almighty God, and we know they are here somewhere. Yes; Brethren of that Spiritual Family, we feel you are here, some in this congregation, who know Christ after the spirit and who have tasted the good word of life and the powers of the world to come. Another method: The Gospel of peace and reconciliation is opened, Aye! The fountain for the support of Christians, whose waters like those of Marah, are bitter to any except the brethren in the Lord--I mean the sacrament of the Lord's supper. I see them come to the feast with joy and humble thanksgiving, and I believe I have found my brethren in Christ. And as brethren may we journey together to the land of promise where none are sick or oppressed, where drivers, hounds, whips and thumbscrews are no more known, forever.

4. As to the method of seeking those of our faith, viz., Methodists, from among others we only intend to declare this an A. M. E. Church, and receive all who make application to join with a desire to flee the wrath to come.

Page 48

III. Wherefore do I seek my Brethren?

1. It was the design of Joseph in seeking his brethren to learn if it was well with them and with their flocks that he might, when he should return to his father, cheer his spirit with news from his sons who were first in his heart and first in his command to Joseph; and also with news from his flocks. But somewhat more comprehensive is our design. Not only do we wish to learn the spiritual and temporal condition of all men we chance to meet, but we desire to do them good; to preach to them Jesus crucified, dead and buried Saviour, and a risen, living Redeemer.

2. To tell to our brethren in affliction that deliverance has come through the wisdom and works of the Most High Yes, my brethren, I have sought you to rejoice with you in your newly gained freedom; to shout with those that shout; to unite heart and voice with you in singing to the Lord who hath triumphed gloriously in overthrowing that horse and his white rider that used with whip in hand ride so lordly over these cotton plantations. I have come to say with you, "The Lord is a man of war, and the Lord God is His name. His right arm doeth marvelous works. Let the redeemed of the Lord bless His holy name." For this have I come, and may God give us a spirit of union, harmony and brotherly love.

3. I seek my brethren in Christ to hear if it is

Page 49

well or ill with them, that I may present their case to Our Father who dwells in the high and holy places, and also to assist them as much as God shall place it in my power so to do in working out their souls' salvation by fearing and serving the Lord with a willing mind and a perfect heart. But, above all, to tell of Jesus who lives on high forever to make intercession for all that come to God by Him. And my Christian brother, there is none able to pluck you out of His hand. If you ever fall it must be by your own will. The devil is not able with all his angelic strength and skill to pluck you from the hand of God. Unless you first consent and say, "I will go." He cannot make us lie, steal, drink rum or swear gainst our will while God is our refuge and strength.

4. I seek Methodists to organize them into churches or societies in accordance with the Methodist Discipline, and under the banner of the African Methodist Episcopal Church of the United States for the sole purpose that they may do more good in the world than possibly could be done by the same number if not properly united together. I come to form you into classes, to give you leaders to reprove or exhort you as the case may require; to instruct you in all the doctrines and rules of government of our church, that God may be glorified in and by us. I come to administer the sacraments

Page 50

of the church to you that you may eat angelic, aye, heavenly food, the precious body and blood of Jesus Christ the Son of God--not really, temporally, but spiritually, by faith.

Lastly, to all peaceably, yet earnestly do I seek you to tell of Jesus who was born in Bethlehem of Judea, lived a life of misery and discomfort, taken by wicked hands, crucified on Calvary's top to purchase for all men, redemption from the consequences of sin; deliverance from the power thereof; a right to the joys of heaven, and actual indwelling peace with God while living in this world. Will you receive me as such a person? Or, will you, like Joseph's brethren, sell me to the Ishmaelites? *

*At this time I was altogether unacquainted with the people, and sought the plainest speech I knew. Not knowing anything of their habits or their thoughts, my effort was to make myself understood.

Will you stand by me as brethren, or will you flee from me and say, "We desire no knowledge of your ways." I am at your mercy. You can support me or you can starve me. But I trust you, I believe you will not leave nor forsake me while I shall be able to present to you an upright character.

May the God that was with Joseph, be with us in every good effort. And to Him be all honor and praise forever. Amen.

Page 51

ROBERT SMALLS

January 12, 1898--Committed to the Committee of the Whole House and ordered to be printed.

Mr. Otjen, from the Committee on War Claims, submitted the following report (to accompany H. R. 1333).

The Committee on War Claims, to whom was referred the bill (H. R. 1333) for the relief of Robert Smalls, submit the following report:

The facts out of which this bill for relief arises will be found stated in a report from the Committee on War Claims of the Fifty-fourth Congress, a copy of which is hereto attached and made a part of this report.

Your committee recommend the passage of the bill.

(House Report No. 3595, 49th Congress, 2nd Session)

The Committee on War claims, to whom was referred the bill (H. R. 1866) authorizing a reappraisement of the steam transport boat Planter, captured by Robert Smalls, and for a distribution of proceeds thereof, submit the following report:

The facts out of which this claim for relief arises will be found stated in House report of the Committee on War Claims, No. 3595, second session Forty-ninth Congress, on file with the papers in the case.

The examination of the claim by your committee leads them substantially to the same conclusions as those reached by the committee of the Forty-ninth Congress. It is therefore deemed unnecessary to recapitulate the facts set forth in that report, a copy of which is hereto attached for information.

Your committee recommend the passage of the bill.

Page 52

(House Report No. 688, 54th Congress, 1st Session)

The Committee on War Claims, to whom was referred the bill (H. R. 10323) for relief of the pilot and crew of the steamer Planter, beg leave to report as follows:

The facts on which this claim is based were investigated by the Committee on Naval Affairs of the Forty-seventh Congress, and were as follows, as embodied in the report of that committee (No. 1887, second session of Forty-seventh Congress):

This claim is rested upon the very valuable services rendered by Robert Smalls to the country during the late war. The record of these has been very carefully investigated, and portions of it are appended as exhibits to this report. They show a degree of courage, well directed by intelligence and patriotism, of which the nation may well be proud, but which for twenty years has been wholly unrecognized by it. The following is a succinct statement and outline of them:

On May 13, 1862, the Confederate steamboat Planter, the special dispatch boat of General Ripley, the Confederate post commander at Charleston, S. C., was taken by Robert Smalls under the following circumstances from the wharf at which she was lying, carried safely out of Charleston Harbor, and delivered to one of the vessels of the Federal fleet then blockading that port:

On the previous day, May 12, the Planter, which had for two weeks been engaged in removing guns from Coles Island to James Island, returned to Charleston. That night all the officers went ashore and slept in the city, leaving on board a crew of eight men, all colored. Among them was Robert Smalls, who was virtually the pilot of the boat, although he was only called a wheelman, because at that time no colored man could have, in fact, been made a pilot. For some time previous he had been watching for an opportunity to carry into execution a plan he

Page 53

had conceived to take the Planter to the Federal fleet. This, he saw, was about as good a chance as he would ever have to do so, and therefore he determined not to lose it? Consulting with the balance of the crew, Smalls found that they were willing to co-operate with him, although two of them afterwards concluded to remain behind. The design was hazardous in the extreme. The boat would have to pass beneath the guns of the forts in the harbor. Failure and detection would have been certain death. Fearful was the venture, but it was made. The daring resolution had been formed, and under command of Robert Smalls wood was taken aboard, steam was put on, and with her valuable cargo of guns and ammunition, intended for Fort Ripley, a new fortification just constructed in the harbor, about 2 o'clock in the morning the Planter silently moved off from her dock, steamed up to North Atlantic Wharf, where Smalls' wife and two children, together with four other women and one other child, and also three men, were waiting to embark. All these were taken on board, and then, at 3:25 A. M., May 13, the Planter started on her perilous adventure, carrying nine men, five women, and three children. Passing Fort Johnson, the Planter's steam whistle blew the usual salute and she proceeded down the bay. Approaching Fort Sumter, Smalls stood in the pilot house leaning out of the window, with his arms folded across his breast, after the manner of Captain Relay, the commander of the boat, and his head covered with the huge straw hat which Captain Relay commonly wore on such occasion.

The signal required to be given by all steamers passing out was blown as coolly as if General Ripley was on board, going out on a tour of inspection. Sumter answered by signal, "All right," and the Planter headed toward Morris Island, then occupied by Hatch's light artillery, and passed

Page 54

beyond the range of Sumter's guns before anybody suspected anything was wrong. When at last the Planter was obviously going toward the Federal fleet off the bar, Sumter signaled toward Morris Island to stop her. But it was too late. As the Planter approached the Federal fleet, a white flag was displayed, but this was not at first discovered, and the Federal steamers, supposing the Confederate rams were coming to attack them, stood out to deep water. But the ship Onward, Captain Nichols, which was not a steamer, remained, opened her ports, and was about to fire on the Planter, when she noticed the flag of truce. As soon as the vessels came within hailing distance of each other, the Planter's errand was explained. Captain Nichols then boarded her, and Smalls delivered the Planter to him. From the Planter Smalls was transferred to the Augusta, the flag ship off the bar, under the command of Captain Parrott, by whom the Planter, with Smalls and her crew, were sent to Port Royal to Rear-Admiral Du Pont, then in commond of the Southern squadron.

Captain Parrot's official letter to Flag Officer Du Pont and Admiral Du Pont's letter to the Secretary of the Navy are appended hereto.

Captain Smalls was soon afterwards ordered to Edisto to join the gunboat Crusader, Captain Rhind. He then proceeded in the Crusader, piloting her and followed by the Planter, to Simmon's Bluff, on Wadmalaw Sound, where a sharp battle was fought between these boats and a Confederate light battery and some infantry. The Confederates were driven out of their works, and the troops on the Planter landed and captured all the tents and provisions of the enemy. This occurred some time in June, 1862.

Captain Smalls continued to act as pilot on board the Planter and the Crusader, and as blockading pilot between Charleston and Beaufort. He made repeated trips up and

Page 55

along the rivers near the coast, pointing out and removing the torpedoes which he himself had assisted in sinking and putting in position. During these trips he was present in several fights at Adam's Run, on the Dawho River, where the Planter was hotly and severely fired upon; also at Rockville, John's Island, and other places. Afterwards he was ordered back to Port Royal, whence he piloted the fleet up Broad River to Pocotaligo, where a very severe battle ensued. Captain Smalls was the pilot on the monitor Keokuk, Captain Ryan, in the memorable attack on Fort Sumter, on the afternoon of the 7th of April, 1863. In this attack the Keokuk was struck ninety-six times, nineteen shots passing through her. She retired from the engagement only to sink on the next morning, near Light-House Inlet. Captain Smalls left her just before she went down, and was taken with the remainder of the crew on board of the Ironsides. The next day the fleet returned to Hilton Head.

When General Gillmore took command Smalls became pilot in the quartermaster's department in the expedition on Morris Island. He was then stationed as pilot of the Stono, where he remained until the United States troops took possession of the south end of Morris Island, when he was put in charge of Light-House Inlet as pilot.

Upon one occasion, in December, 1863, while the Planter then under Captain Nickerson, was sailing through Folly Island Creek the Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened a very hot fire upon her. Captain Nickerson became demoralized and left the pilot house and secured himself in the coal bunker. Smalls was on the deck, and finding out that the captain had deserted his post, entered the pilot house, took command of the boat, and carried her safely out of the reach of the guns. For this conduct he was promoted by order of General Gillmore, commanding the Department of the South, to the rank of captain,

Page 56

and was ordered to act as captain of the Planter, which was used as a supply boat along the coast until the end of the war. In September, 1866, he carried his boat to Baltimore, where she was put out of commission and sold.