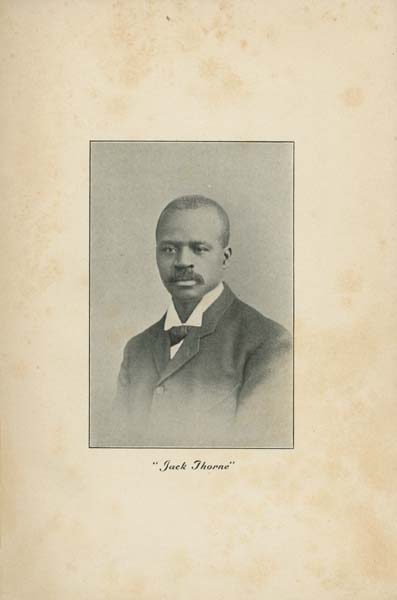

"Eagle Clippings" by Jack Thorne, Newspaper Correspondent and Story Teller, A Collection of His Writings to Various Newspapers:

Electronic Edition.

Thorne, Jack, b. 1863.

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Elizabeth S. Wright

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Marisa Ramírez and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2004

ca. 245K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2004.

Source Description:

(title page) " Eagle Clippings " by Jack Thorne, Newspaper Correspondent and Story Teller, A Collection of His Writings to Various Newspapers

(cover) Eagle Clippings by "Jack Thorne", Newspaper Correspondent and Story Teller.

Jack Thorne

1-116 p., ill.

[Brooklyn, N.Y.]

[D. B. Fulton]

[c1907]

Call number VC070.45 F97e (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Italian

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- North Carolina.

- African Americans -- Social conditions.

- Dixon, Thomas, 1864-1946.

- Fulton, Lavinia Robinson, 1837?-1904.

- Lowry, Henry Berry.

- Pullman porters -- Anecdotes.

- Reconstruction (U.S. history, 1865-1877)

- Southern States -- Race relations.

Revision History:

- 2005-01-11,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2004-08-03,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2004-05-27,

Marisa Ramírez

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2004-03-04,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

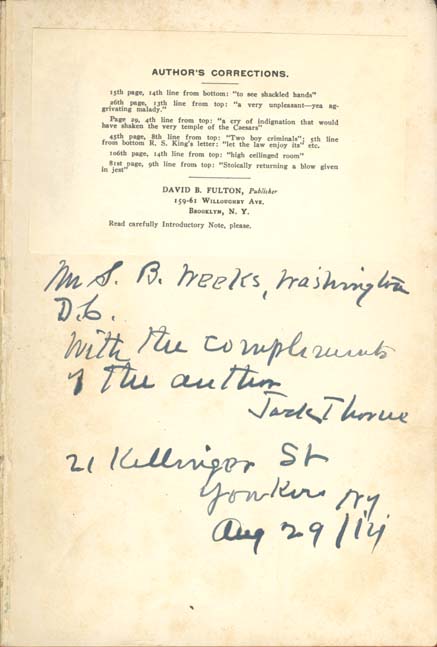

[Author's Inscription to Mr. S. B. Weeks]

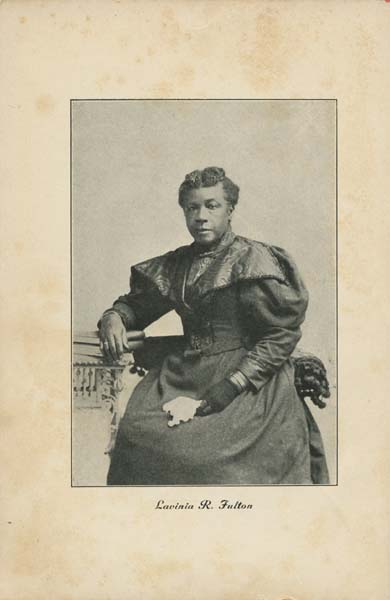

Lavinia R. Fulton

"Jack Thorne"

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Image Verso]

Page i

AUTHOR'S CORRECTIONS.

15th page, 14th line from bottom: "to see shackled hands"

26th page, 13th line from top: "a very unpleasant--yea aggrivating malady."

Page 29, 4th line from top: "a cry of indignation that would have shaken the very temple of the Caesars"

45th page, 8th line from top: "Two boy criminals": 5th line from bottom R. S. King's letter: "let the law enjoy its" etc.

106th page, 14th line from top: "high ceilinged room"

81st page, 9th line from top: "Stoically returning a blow given in jest"

DAVID B. FULTON, Publisher

159-61 WILLOUGHBY AVE.

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

Read carefully Introductory Note, please.

[Handwritten in this Edition:]

Mr. S. B. Weeks, Washington D.C.

With the compliments of the author

Jack Thorne

21 Killinger St

Yonkers N.Y.

Aug 29 /14

"EAGLE CLIPPINGS"

BY

JACK THORNE

NEWSPAPER CORRESPONDENT AND

STORY TELLER

A COLLECTION OF HIS WRITINGS TO

VARIOUS NEWSPAPERS

Page verso

GRATEFULLY DEDICATED TO THE SONS OF NORTH CAROLINA, OF BOROUGH OF BROOKLYN, CITY OF NEW YORK

Copyrighted by D. B. Fulton

All rights reserved

Page 3

Introductory Note

It was said to me one day, by a once highly esteemed friend of mine, during a hot controversy over a disputed bill for printing, that I was an eccentric on the Race question. This taunt from the lips of one of my own people, a man who had my confidence, who seemed heartily in sympathy with me, advising me in the construction of at least a few of my many contributions to daily and weekly papers, somewhat chilled my ardor in the work of defense--for after all, in all of my writings on the Race question, I have simply been on the defensive, answering traducers and endeavoring to ward off the blows aimed at my people by the enemy.

When constructing Hanover, many of my friends who listened to the readings, were apprehensive and fearful for my safety, in spite of the fact that I was so far removed from the scene of the awful tragedy which the story relates. Other readers of Hanover and other contributions have said with no feigned anxiety, "Your pen is a very venomous weapon. You are doubtless right; I admire your grit, but you might make it a trifle milder," etc. These apprehensions were not without warrant. I fully believe that the attempt on the part of the officials of the institution in which I was employed for four years, to injure my reputation, and send me from their employ, branded as a felon, was the result of my defense of my people in the columns of the "Eagle"; that the "Eagle's" final refusal to further consider my contributions, are the result of influences

Page 4

brought to bear from the same source. Yet in the following pages I will prove to the reader that every article from my pen upon the Race question was called forth by the anamidversions hurled from the other side.

Although the entire contents of this little book are not clippings from the columns of the "Brooklyn Daily Eagle," I have thought it best to give it the title "Eagle Clippings," because I hold the "Eagle" in high esteem for its broad democracy and bravery in the treatment of its correspondents.

"The Eagle," a Democratic organ, professes no friendship for the Negro race, yet it has generally allowed the writer to wage battles through its columns by giving abundant space for articles that were considered by the friendly Republican editors too sweeping for publication. On account of the "Eagle's" often disparaging editorials on the Race question, many of my friends have purchased a copy of the paper only when informed that an article of mine was forthcoming.

To such friends is this little volume especially presented, that they may enjoy some of the many contributions on subjects nearest their hearts and mine.

I plead for the acceptance of this little volume, not alone because of my bold defense of my people I became the object of the spleen of those who possessed the power to rob me of the means of support, but because its contents are the outpourings of a heart full of love for a maligned race and jealous of their wrongs. While, no doubt, other contributors have been enabled to demand something for their time and talents, the author of "Eagle Clippings" has been glad to, so far, be so indulged in the prosecution of his loved work as to have it accepted gratis by the great "Brooklyn Daily Eagle" and other periodicals. This should kindle a sympathetic flame in the hearts of my friends, for I believe I have many, to compensate me for the labors in behalf of the race.

JACK THORNE.

Page 5

THE DEATH OF LAVINA ROBINSON FULTON.

(From The Standard Union.)

Lavinia Robinson Fulton, mother of D. B. Fulton, better known as "Jack Thorne," and one of the strongest writers of the race, died at her late residence, 465 Baltic Street, last Monday evening, from paralysis. The funeral services will be held to-morrow at 2 P. M. at the Concord Baptist Church of Christ.

Lavinia Robinson was born in Robeson County, North Carolina, about sixty-seven years ago. She was the eldest of fourteen children of Hamlet and Amy Robinson. Sent away from her parents at a very early age, she grew up as many slave children, without the affection, love and counsel of a mother. Through the indulgence of her master she learned when very young to read the Bible and was converted when about thirteen years of age. She entered the Baptist Church of which her master was deacon, and was baptized by the Rev. James McDonald, a famous Scotch divine, known as the "silver-tongued orator of the Cumberland," the Talmage of the early 40's. Although like all slave women, environed by circumstances in no way conducive to upright living, Lavinia Robinson Fulton lived a pure, upright and consistent life, always seeking the companionship of those whose lives accorded with her own. Married to Benjamin Fulton at the age of fourteen, she bore him ten children, five of whom now live, four in Brooklyn. One is with the father in North Carolina. To her children she was never demonstrative, but sought to prepare them for the real earnest battle of life. She settled in Wilmington in 1867, and saw in the American Missionary Association, then at work among the freedmen there, the much desired opportunity to improve herself and educate her children, and immediately put herself in touch with these people. In 1875 she became one of the founders

Page 6

of the First Congregational Church, of Wilmington, N. C. Every opportunity for moral, religious and intellectual advancement her children have enjoyed has come to them through the self-sacrificing devotion and the sterling Christian character of this mother. Her nearly ten years' residence in Brooklyn have been years of unceasing toil, yet she never let pass an opportunity to speak a word for her Master whom she has faithfully and unwaveringly followed, going out when the opportunity presented itself to participate in the Salvation Army services to which she had become very much attached. Her children never grew too old to be her constant care and anxiety and the burden of her prayers.

BROOKLYN, N. Y., July 16, 1904.

Mr. Benjamin Fulton,

Middle Sound, North Carolina.

Dear Brother Ben:--

The enclosed clipping is the press announcement of the death of mother which occurred on the 4th instant. She was ill but a very short period. Up to about three months ago, she was apparently in the best of health; in fact, her health was generally better here than in the South. But being constantly on the go, she contracted quite a good deal of cold. Sister Hattie tried to persuade her more than a year ago to take a rest, but she would not until compelled to give up. She died as she lived, a devoted mother, an earnest Christian. When the end came she was at sister's, and we all were with her but you. She had, since the riots at Wilmington, expressed an unwillingness to be buried there, so we buried her here, and the funeral was attended by many old Wilmington friends. No nobler mother ever lived; no truer Christian ever died. She desired much to see you; will you make it your aim to meet her on the other side? May we hear from you soon? I would have written you sooner, but I have just gotten your address from Mrs. Powell. Hoping that you all are very well, I am,

Yours affectionately,

DAVID.

502 Fulton Street.

Page 7

A DOCK LABORER

Experiences of One Man Who Came to the Metropolis in

the Late Eighties, Looking for Honest Employment.

(From The Brooklyn Citizen.)

From the time of my arrival in New York in '87, and entering the employ of the Pullman Palace Car Co. in '88, up to Dec., 1905, I had been able to give a pretty accurate account of my time--nine years in the Palace car service, four years in a large music house in New York City, two years at odd jobs, and at the close of the year 1905 I had about wound up four years in the employ of the Central Branch of The Young Men's Christian Association of Brooklyn, feeling that a change of atmosphere would perhaps conduce toward the strengthening of my faith in the efficacy of Christian religion which contact with "Scribes" had somewhat weakened. The uninitiated, perusing the columns of the great New York dailies with their innumerable "Help Wanted" advertisements, would readily conclude that the seeking of employment in the great Metropolis need be no irksome task to any one. But the major portion of these want ads[.] are mere will-o'-the-wisps, put there apparently to tantalize and to throw into the abyss of despair honest seekers after the tangible. Such announcements as "Wanted--Cooks, waiters, chambermaids, coachmen, butlers, hall-boys, bellmen, laundresses," etc., etc., are invariably the fabrications of unscrupulous employment agents, who spread their nets to catch the unwary, whose money they greedily pocket and hurry them off to fill positions which, to their knowledge, are already filled through

Page 8

other agencies. Experience had taught me that in seeking work in New York, both of these mediums were to be eschewed. My first position, which cost me just half of my fortune, was a place way out in Fordham, where I was engaged to drive a horse and milk the cow. I knew little about horses and nothing about cows. In less than a week I had broken the shaft of the man's buggy, was dismissed, and with my belongings was on my way back to the shrewd son of Abraham, who had followed me to the door on the day of my departure from his office, rubbing his clammy hands and whining: "Eef th' blace dus nod suit you, vhy cum back an' I gif you a nudder." But when he saw me approaching the office a second time he met me at the door and, holding up his hands in feigned horror, swore by the beard of the prophet that he had fulfilled his contract and would do no more. If he did not see greenness in my face, he took the chance at bluffing me out of three dollars, and succeeded. This well-remembered experience turned me into other channels in search of work this time. Accepting the agency of a Health and Accident Insurance Company, at the end of a month of canvassing I had on my book the names of a host of sympathetic friends who, although well provided for in that line, were, on account of their great love for me, ready to invest in more insurance. One very dear friend to whom I thought I had convincingly set forth the advantages and inducements my company offered, and why a woman of her environments and temperament would profit by taking out a policy therein, and who had, in turn, eloquently acquiesced and expressed her desire and determination to subscribe, had at the conclusion of two weeks, the time appointed for the issuing of the policy, prepared such an eloquent speech in support of a demurrer, that, after listening in amazement to it, I threw aside my insurance outfit in disgust, purchased hook and overalls and sought employment among the dock laborers.

It was in 1892 that the Ward Steamship Company of New York terminated a series of strikes among its dock laborers and stevedores, entailing great financial loss, by substituting Negro labor for Irish and Italian. The Irishman is the very embodiment of discontent, the instigator of

Page 9

nearly all the troubles in the labor field, the inaugurator of political upheavals and race clashings. Ever ready to strike for higher wages and shorter hours, the Irishman would burn his own dwelling from over his head if he thought that thereby he might do injury to an unyielding employer. The Ward Steamship Company, financially embarassed by frequent revolutions in its labor department, and at the mercy of labor unions had yielded step by step until the longshoreman's pay had advanced from thirty to forty-five cents an hour. But the demand for fifty cents was the straw that broke the camel's back. The Italians who, with difficulty supplanted the Irish and went into the holds of the ships to work for twenty-five cents per hour, were not sufficiently bulky nor experienced to insure independence of the lusty son of Erin, and the Negro, who, previous to this time, had only been allowed to step in here and there along the water front, was called in to take charge of the work of loading and discharging the great ships of the Ward Steamship Company. The Negro workman, pushing out over the North and West, is confronted by more serious and exasperating obstacles than any other human creature. Securing work in big corporations only as a strike-breaker, he, in many instances, has only been retained until the white man chose to return to work. But the Ward Steamship Company had called to its rescue, men schooled in Yankee duplicity, who did not "turn to" until this very important matter was settled. But the scale of wages made by the Italian strike-breaker was not advanced in favor of the efficient black stevedore. And the twelve years of unprecedented prosperity, during which the company has had to double its carrying capacity by adding in its fleet several large and more commodious ships, an advance in wages from twenty-five cents an hour so far has never been offered these benefactors, who freed the company from the meshes of labor unions, brought order out of chaos and started them on the road to prosperity. It must not be conceded that because of its rough character, the work of the stevedore is a calling that does not require intelligence, cool-headedness and skill; for without coolness and thorough knowledge on the part of those appointed to direct it,

Page 10

the work of loading and unloading these great ships would be attended by far greater loss of life and limb than is now recorded. It was a cold morning in the month of February when I joined the anxious crowd of laborers at Pier 15, East River, Brooklyn side, waiting to be "shaped." To be shaped is to secure at the timekeeper's window a brass check with a number engraved upon it, which is written in his book opposite your name, and passing the foreman who engages you, you call out this number, which is jotted down in his book. On quitting work each man calls out his number to the timekeeper, and returning, reports both to timekeeper and foreman. "Push in," said a sympathetic fellow, noticing my embarrassment, "your chance may be as good as the oldest; no man has a cinch here."

"Stand in line and take your turn," said another man, as he noticed me endeavoring to push my truck past the fellow in front of me. "The Irishman tries to make a job last as long as possible, while the Negro sings and runs himself out of work." My first day's work consisted of unloading fruit and pig lead; and as I climbed the hill homeward at the conclusion of the day my limbs almost refused to support me. The following day, still sore and stiff from the previous day's toil, I reported again at Pier 15, and by sheer ambition trudged through another day of the hardest toil of my life. In discharging ships, foremen may employ as many as twenty men in their gangs, but they dwindle to sixteen when loading. Failing to get a "shape" on the third day, I wended my way back home to return in the evening to try my luck with the night gangs. To my mind, it requires more than ordinary courage on the part of a new and inexperienced hand to join a company of men going into a ship's hold to store freight, aided only by the light of lanterns. The gang in which I worked began in the ship's hold to be shifted to the docks, and from thence off shore to hoist freight from one of the many lighters which flanked the great vessel. The angry, black waters, lashed into fury by the fierce cold winds, seemed anxiously waiting to swallow into its depths the timid wretch who, stumbling blindly over the many pitfalls, chanced to miss his footing. This, together with the oaths of the experienced

Page 11

and unsympathetic workmen, the ear-piercing calls of the gangwayman, the deafening roar of machinery so exasperated and confused me that I was tempted to climb back upon the dock and scamper off for home. But as the night grew old and the owl-like hoot of craft in the great harbor lessened, the lights in the distant towers went out one by one and the great bridge, no longer disturbed by moving cars and the tread of restless feet, stood there calm and tranquil in the glimmering shadows, I became more reconciled to my surroundings and the task became less irksome. Current stories of crime, of midnight assassinations, of suicides, give New York harbor at dead of night a weird and fantastic aspect. Yet in spite of all this it is a fascinating sight. I soon discovered that one man's chances were not, if green, as good as another old and experienced hand, and justly so. The mastery of stevedore work is as difficult a task as the mastery of algebra, it seems to me. It was perfectly natural for the foremen to cull out the men whom they knew could do creditable work. My first employer was Capt. John Simonds (colored), who was doubtless moved more by my willingness than my value as a workman, and though I got in now and then with Powell, with Rainey and with Butler, it seemed less difficult to shape with Simonds. For quite a month or more I beat about the decks, following the gangs from pier to pier and from sugar house to sugar house with varying luck. One evening at Erie Basin, I joined the gang of a foreman whom they called "Buster Brown." "Buster Brown" was a wild, swearing Negro of the Guinea type, with protruding forehead, staring eyes and heavy lips that could utter oaths and filthy epithets that would put a pirate to blush. Brown was the type of Negro indespensable to the overseer of the slave plantation, who wished to wring out the very last drop of blood from his chattels; who often as "drivers" strung up and lashed their own mothers. It is a type of native used by the British now plundering South Africa, to get the most out of the workers in the mines. This fellow kept the air lurid with oaths and vulgarity, buldozing the men, threatening them with his fist and with his gun, and in turn cringing like a cur when addressed by the white supervisor. I

Page 12

looked at this Negro both in pity and disgust and wondered what kind of a home it was over which he presided. Although the night was cold and men were constantly dropping out to warm up at a near-by saloon. I stuck to my post lest the impetuosity of this foreman tempt me to lay his thick head upon the dock and thereby lose a night's work. Fortunately, "Baster Brown" is not the prevailing type of stevedore; I found a sufficient number of sober, industrious and goodly disposed men engaged in work there to make it quite a pleasant place to be. There are many incidents during my employ there on the docks that I recall with pleasure, for I believe the Negro works with a lighter heart, and infuses more music and fun into labor than any other human being. Most of these men are from Virginia and the Carolinas, where music and laughter drive away the irksomeness of toil. No group of men was without its jester, who was often a Godsend to the discouraged and melancholy. I recall with a great deal of mirth the side-splitting jokes gotten off by "Squire Rigger" on "Sheep" and "Sheep's" witty retorts and sarcastic flings at "Rabbit," or Philip Hooper's droll, yet mirth-provoking tales of his adventures. Phil had traveled extensively and worked at nearly every imaginable calling in the labor world, and his retentive memory was never taxed for some interesting, instructive and yet amusing story.

Page 13

THE GREAT WHITE WAY.

To Mr. Jno. E. Robinson, Ed. of The "Mirror."

To some of us who had lived South where most city streets are wide sandy deserts, the first invasion of Broadway, New York, was not without a feeling of disappointment; for this lovely old thoroughfare which, beginning at Battery Park, winds like a river northward through Manhattan Island is anything but "broad." Often as I stood upon the curbstone of this overcrowded street, have I imagined that I could hear its painful cry of protest as it groaned under the weight of traffic, and wishing that the clumsy vehicles of commerce might be driven into some other avenue, so that the stranger, proud of its fame might with less annoyance and apprehension feast his eyes upon the historic landmarks that border it on either side. When I first beheld Broadway, Jake Sharp's bribery had deprived it somewhat of its attractiveness; for the horse-car had just invaded it, adding to the congestion and consequent discomfort of pedestrians, and changing it from the aristocratic highway of hansom cabs of former times.

In spite of the protest of the citizens of the great metropolis, "cabby," with his smart livery, his soft, suave and polite "want-a-cab?" was to be forever hushed by the ear-piercing jingle of the car bells and the coarse yells of the driver. But this change did not rob the old thoroughfare of its interest and power to fascinate and charm, for the people soon forgot this "wanton disregard for our wishes" and became reconciled to the new order of things. And how the old street has grown in beauty and grandeur within the last twenty years! Now it's "The Great White Way" of modern structures of marble and granite. Have you ever walked the streets of New York without a home? A stroll along Broadway drives away melancholy and

Page 14

makes the homeless and despised forgetful of his misery; for there is an inexplicable feeling of warmth in the glow of its myriads of electric lights, and the winter snow that falls on Broadway seems to hit the cheeks with apologetic tenderness.

The homeless outcast from beneath the chilly glare of the lights of Fifth Avenue, where he is jostled aside by the footmen and run down by the luxuriant coaches of haughty millionaires is often saved from a suicide's grave by the warmth and cheer dispensed by the lights of Broadway. Broadway, where sympathies are blended and everybody is kin; where the recluse crawls out of his shell; where the miser loosens his purse strings and for the time being is a jolly good fellow. Broadway is the lane of comedy, comedy that flows in such immense volume that tragedy the most revolting, can only cause a momentary ebb. It is said by some people that in handsomely gowned and pretty colored American girls, Chicago outclasses New York. But I wonder if any of these alleged authorities ever stood for an hour or more on upper Broadway at the junction of Sixth Avenue and Thirty-third Street, or lined up with the "chappies" in front of St. Mark's at the close of an afternoon Sunday lyceum service to watch the parade of beauty. I am entitled to a vote on this question. I have strolled the fashionable thoroughfares of nearly all the large American cities. But for wealth of beauty, and of raiment, for the bountifulness of pleasure and revelry of mirth and good cheer, give me dear old Broadway, fraught with sweet, bitter memories.

Page 15

DR. JACOBS AND HIS CHOIR

To the Editor of "The Standard Union":

In the days of slavery few plantations in the South were without their Negro spiritual advisers, men devout, chosen from among their fellow bondsmen, who were permitted to go freely from plantation to plantation to pray and exhort among their brethren. In many communities in North Carolina master and slave worshipped in the same church, the whites monopolizing the mornings and evenings of the First Day, while in the afternoons the Negro from the same pulpit preached to his own people. Very often during these services the master sat in the audience an attentive and reverent worshiper; for there was a pathos in the mournful music of the slave, an emotion that permeated his preaching and his prayers that strangely fascinated the dominant race in those days. It must have been a strange and wonderful sight to the white man to witness the fervency with which the slave worshiped the God who had so permitted it that he owned not himself; to see shackel hands raised in exaltation, and tears of joy unspeakable streaming down cheeks furrowed and scarred by hardship. The intense enjoyment of these brief intervals of freedom to worship God on the part of his chattels doubtless had the effect of easing the conscience of the oppressor and justified the institution. The master thoroughly enjoyed the worship of the slave, especially his singing. He often lingered about the church door to catch the last strains of the plaintive melody that gushed from bleeding hearts. The song of the captive mourning for his lover, ruthlessly sold away to some distant land, was prompted by far different emotions than the shouts from "corn shuckings," but the effect was the same upon the ear of the calloused oppressor whose descendants

Page 16

now regard the slave regime as a benefaction. This fixed time for the worship of the slave in North Carolina did not debar him from a place in galleries when his master worshiped. The eloquence that floated out from the lips of the cultured and refined ministry and the music of trained voices in the choir loft were listened to with great profit by the captive, destined some day not only to own himself but his church and his pew, for at the close of the war the number of negroes in the South who knew more than the mere rudiments of music was surprising. And as there was a strong desire on the part of the race to diseard plantation melodies, reminders of cruel bondage, and learn classical music, he who could teach vocal music had an inviting field in which to work. The town of New Berne, N. C., for many years after the war was noted for the great love for music among its colored people, the major portion of the Sunday service in every church and schoolhouse being devoted to the teaching of vocal music. And now there are but few colored people hailing from that section of the old North State that cannot both read and sing music.

But as in most colored churches, collections are lifted to the accompaniment of vocal music to the overtaxing of choirs, the plantation song has not entirely lost its popularity, and the composer of rude religious ballads is still to be reckoned among the indispensible adjuncts in the spreading of the Gospel. In some districts among the African Methodist people the minister who can sing well, as well as preach well, has a more satisfactory financial report to present at the annual conference than he who has but the one talent. The most popular and successful composer of sacred ballads I recall was one, the Rev. Mr. Hunter, of the Zion Methodist connection, whose "Go Down, Moses," "Oh, Daniel," etc., electrified the worshipers of old "Christian Chapel," in Wilmington, North Carolina, so many years ago. When Dr. Hunter came to town and stood in the pulpit of the old chapel, the choir was for the time being forgotten by the audience in their eagerness to catch the melody and follow in the strain of new song sure to issue from the mouth of this great singer. But in our more modern pulpits, especially in the North, taste for the classic and refined in

Page 17

music is on the ascendancy. And we can safely consider Dr. F. M. Jacobs, of the Zion Methodist Church, in Bridge Street, as among the foremost exponents of this gratifying regime. Although Dr. Jacobs is not without a love for the old slave melodies, which he can sing with the zest of the most ardent Methodist, he is more in love with the classic and refined, and is as much at home in the rendition of ["]Inflammatus," by Rossini, as the simplest Negro melody.

Paul Fulton, the new choirmaster of the Zion Memorial Church choir, born in Cumberland County, N. C., and educated in the public schools of Wilmington, received his musical training under Mrs. Janet Gay Dodge, one of the most proficient, thorough and painstaking teachers of the art that ever went South from New England. For a number of years Mr. Fulton trained and was at the head of one of the best organizations of male voices in the State of North Carolina. But since he has lived North he has taken up but little time with the music world. The disinclination of Negro churches to pay singers gives to choristers an abundant amount of care and worry in the training of volunteers who are mostly amateurs. This state of things has worked to the detriment of choristers who are often over taxed and worn out leading choruses, prompted in many instances by the ambition to be the stars. Mr. Fulton's method is to train each individual singer to be self dependent, and thereby have a choir that will not be compelled to lean upon its chorister. Those who shall visit Zion Memorial Church during the coming season will have the pleasure of enjoying some novel and entertaining musical programmes.

Page 18

THE ADDRESS OF JOHN TEMPLE GRAVES

Of Atlanta, Georgia, as Published in the Brooklyn Daily

Eagle.

CHICAGO, September 3d.

The University of Chicago held its forty-eighth convention and the principal speaker from abroad was John Temple Graves, of Atlanta. He spoke on "The Problem of the Races," and his long address will probably cause a furor throughout the country. Mr. Graves made a great reputation for oratory at Chautauqua at the lynching conference, but his address to-day was of a different nature. He gave a complete exposition of the race problem as the South sees it; its causes, effect, and his theory of its solution. Mr. Graves' main points were that the only solution possible is the complete separation of the races; that the Negroes ought to have free transportation to the Philippines; that the Islands should be turned over to them for their own absolute control as a state; that no whites should vote there and no negroes should vote here; that the South could get along without them, because the last census shows the Negroes have not had a majority share in the raising of crops recently.

Mr. Graves said in part: "Fortunate am I, and happy in that I bring the convictions of this hour to a platform so free and to an atmosphere so impartial. Questions of abstract policy--problems of humanity--bearing a hint of section or a complication of party are not for the ears of faction or for the passing of politics. Upon the fierce and heated bosom of established prejudice the cold stream of reason falls too frequently to steam and hissing, and men who have convictions that are rather definite than popular

Page 19

may thank God for the calmer air of universities and for the clear and unbiased minds of students seeking truth."

Then Mr. Graves went on to state his problem--the conditions in the last forty years that brought the race matter to the fore. The freeing of the slaves and making them the equal of their former masters made two opposite, unequal, and antagonistic races stand side by side. He said the equation was this: "There they are--master and slave--civilized and half-civilized, strong and weak, conquoring and servile, twentieth century and twelfth century--thirteen hundred years apart--set by a strange and incomprehensible edict of statesmanship or of passion set by the Constitution and the law, the weakest race on earth and the strongest race on earth, side by side, on equal terms to bear an equal part in the conduct and responsibility of the greatest government the world ever saw. It was an experiment without a precedent in history and without a promise in the annals of man. The experiment has had thirty-eight years of trial, backed by the power of the Federal Government and by the sympathy of the world. It has failed. From the beginning to the hour that holds us, it has failed.

"In a land of light and liberty, in an age of enlightenment and law, the women of the South are prisoners to danger and to fear. While your women may walk from suburb to suburb and from township to township without an escort and without alarm, there is not a woman of the South--wife or daughter--who would be permitted, or who would dare, to walk at twilight unguarded through the residence streets of a populous town or to ride the outside highways at midday."

A REPLY TO THE HON, JOHN TEMPLE GRAVES

[CHICAGO SPEECH]

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

I was quite a small boy when, in 1874, three men entered the school of which I was a pupil and announced the death of Charles Sumner, a name which but few of us had ever heard. "Charles Sumner is dead!" was the first sentence uttered by the first speaker, who went on to tell us how

Page 20

deeply the Nation was affected by the death of this good man. "Who was Charles Sumner, and what of him?" was the query that went from pupil to pupil, for the stranger in his eulogy did not satisfactorily enlighten us on that point. The fact that we had not heard of him then makes his name dearer to me now as I recall that eventful incident, for Charles Sumner shall be numbered with the elect and precious who shall inquire of the King in that day: "Lord, when saw we thee a hungered and fed thee? or thirsty and gave thee drink? When saw we thee a stranger and took thee in? or naked and clothed thee?" And the King shall answer and say unto them, " 'Verily, verily, I say unto you, in as much as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.' " This man had given his best days, given his best energies contending for the rights of a race too ignorant and obscure to even realize that such efforts were being put forth in their behalf, or that such a man as Charles Sumner existed. It is upon such characters that a strong nation rests, for it takes such to build a strong nation and uphold it; men who did right because it was right; men who were willing to do and dare for the oppressed from whom there could come no earthly reward. Such characters grow in magnitude as the years recede, and men come to understand the truths they championed. Many of those who listened to the speech delivered by John Temple Graves at the Chicago University a few days ago, have doubtless visited Lincoln Park in that city, to gaze upon the rugged features of that great leader of men whose bronze statue stands there looking sadly down upon the throngs that pass it. Their minds must move back to his early career in Illinois, and his many combats with Stephen A. Douglass, Douglass the invincible, who could lie like truth, to whom Lincoln was no match as an orator. Yet the name of Lincoln, who believed in right-eousness and simple truth, will live in the hearts of the American people when that of Douglass is forgotten. Such men as Lincoln never boasted of a "white man's country;" but the burden of their prayers was that "nation of the people, for the people and by the people might not perish from the land." When the nations of the old world think

Page 21

of the greatness and grand achievements of this Republic, such characters as Lincoln, Phillips, Sumner, Whittier, Beecher, Garrison stand out as the bulwarks upon which it rests, and not of those who have contributed the least, and yet are doing the most boasting. What did the people of Chicago assemble for to hear, a rational being, a man clothed in his right mind? Or was it not rather to listen to a man who had lain down in Georgia and dreamed a dream, and before fully awakened from the stupor of a long sleep, stalked forth to relate it? Suppose there was a possibility of carrying Mr. Graves' colonizing scheme into execution, how long would it be before there would be a John Temple Graves in the Philippines, whining for the separation of races and saying, "This is a white man's country." The white man is there now, grabbing land, speculating, stirring up race hatred and mongrelizing an already mongrel people. Is not Governor Taft unpopular over there because he desired to give the Filipino a say-so in the government of his own country? Where is there a domain from the dense interior of darkest Africa to the Land of the Midnight Sun that Mr. Graves' race is not found, subjugating, killing and tyranizing? The Negro cannot walk on the sidewalks in the Transvaal. That's a white man's country, too. That "all conquoring race" Mr. Graves boasts of is everywhere, seeking to turn the world into a trust and kick all the other races off of it. "Civilizing and Christianizing," you say? It is no satisfaction to me to behold in the jungles of Patigonia the Christian(?) white man's cottage where the hut of the savage once stood when I reflect upon the fact that to put that cottage there it cost the lives of perhaps a thousand human beings, fashioned by the hand of God to live on this earth and enjoy unmolested a persuit of happiness. What manner of people are those to whom the sweetest music is the groans and wails of the suffering, and to whose feet the softest cushion is the neck of the down-trodden? Where shall rest be found? The view of the distinguished gentleman from Georgia is that it's to be found neither in Heaven nor Hell for any race but the white race. His conception of such things is so narrow and contracted that his people must have the right of way because

Page 22

cause God did not call the worlds into existence without consulting them, neither can God run the universe without them. In Paradise the white man is to occupy all the front seats by the Jasper Sea, and the darker races must stand behind and fan him. And if he should be so unfortunate as to go to Hell he will seek a nigger or a Chinaman to hold between him and the fire. It's passing strange that Mr. Graves allowed the Almighty to create all these weaker races for his people to look after and keep in their places. It would have saved the white man from the commission of many a black sin had God created the whole world solely for him to bustle in.

"In a land of light and liberty the women of the South are prisoners to fear," etc. Now this assertion, when read, will be more startling to the women of Atlanta than to Mr. Graves' Chicago audience. The white woman may walk from "suburb to suburb" with far more safety in Atlanta than in Chicago. To say that the Southern white woman is unsafe because of the presence of the Negro is a damaging misstatement. The Southern lady of wealth is continually surrounded by her trusted colored servants, male and female, and her environments have always been such as to render her as fearless of the Negro as a pet cat. Until they were past the age of twenty, the only escort to teas and to parties and such like the daughters of one of the leading merchants of my native town had was their Negro butler. No one turned to gaze after the wife of another prominent citizen of that town who thought nothing of going through the streets leaning upon the arm of her Negro butler. Mr. Graves, in order to strengthen his colonization theory, would malign the women of his race

Brooklyn, Sept. 19th, 1903.

Page 23

MEMORIAL DAY IN THE SOUTH

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

As Decoration Day draws nigh, recollections of the struggle of 1861, which so tried the two sections of our country, become more vivid, and the many years that have passed since then seem less distant. The veteran in his faded coat of blue, his rugged visage and empty sleeve; the militiaman in brilliant uniform; citizens in holiday attire, booming cannon and martial music, give to that particular day a significance which apparently no other day possesses. While in the North we celebrate in gala attire and bands and drum corps blare out patriotic airs, in the South the observance is in striking contrast; all is funereal, solemn and sedate. With arms reversed, the veteran, with slow and measured tread follows behind muffled drums and bands play dirges, while choirs sing most solemn and touching music. While the 30th of May is universally observed for the decoration of the graves of Union dead, the Daughters of the Confederacy and other such organizations in the South, although such a day is observed in every Southern State, do not move in concert. In the far Southern States, where spring puts on her richest attire in early April, Confederate graves are decorated in that month, while in States further North, a day in May is observed. In North Carolina it is the 10th of May; in Virginia, it's the 30th. This is an observance of the most intense interest to lovers of the "Lost Cause." An air of profound sadness and thoughtfulness pervades the very atmosphere, and the gray veteran again salutes the "Stars and Bars" which hang in profusion about the speakers' stand and wave above the Confederate dead. Father Ryan's famous poem, "The Conquored Banner," is recited with a pathos that is touching. Old wounds bleed a-fresh as impassioned orators tell of the causes that led up to the struggle; the justness of the Southern side and the bravery of the Southern soldier. Pickett's gallant charge at Gettysburg is rehearsed with fervor; what might have been gained to the South on that gory field had Lee

Page 24

listened to the advice of Longstreet is also regretfully told, together with the story of the foolhardiness of Sidney Johnston at Shiloh, which lost the West to the Confederacy. But on the 30th of May, when Union soldiers' graves are decorated, a different program is rendered. There, over those grass-covered mounds, other orators -- nowadays mostly colored men -- tell of the victories of the "Silent Man" at Donaldson, at Shiloh, at Vicksburg, at Chattanooga, at Petersburg and Richmond, and of of Sherman's famous March to the Sea. The decoration of these graves is, and has ever been, done almost solely by Afro-American women. And when we consider the fact that nearly all of the men who fell in that awful struggle sleep South of Mason's and Dixon's line, we can appreciate the importance of the part the Afro-American woman plays in this work of love. At Richmond, Culpepper, Wilmington, Salisbury, Sailsbury, S. C., Nashville, Chattanooga, Memphis and other places beneath acres upon acres of grass-covered mounds.

"Asleep are the ranks of the dead"--Union dead. The Government provides only for the placing of a small American flag on that day upon each headstone, no more. But it is the loving hand of black woman and child that places the rose, the jasmine, the lilac and forget-me-not there, with wreathes of cedar and of pine: so that wafted upon the breeze which comes upward from that hallowed ground is the breath of sweet flowers. What shall be done for this obscure Schunamite who, for so many years, has faithfully performed this work of love? "Shall we mention her to the King? or shall we ship her to the Philippines?["] The Grand Army veteran will doubtless say "No," when he looks backward and thinks of Andersonville, Libbey, Florence and Danville, and of the fate that might have been his had it not been for the devotion of some colored woman or boy who hid him in kitchen loft or barn or hay stack, from the heartless rebel, and under cover of darkness, piloted him safely into Union lines.

"Oh Lord of hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget, lest we forget."

To the Afro-American woman of the South on that day

Page 25

will come vivid recollections of the inexplicable gloom that pervaded the land everywhere when John Brown went to the scaffold, or the excitement attending the bombardment of Fort Sumpter, the hastening northward of the soldier in gray, of the constant scudding off of husband, brother or father to break through rebel lines to fight on "the Lord's side." She will hear again the sad wail of the massacred at Fort Pillow, see those black forms dashing toward the parapets of Fort Wagner and hear again the thunderings of the awful crater at Petersburg. With this must come the consoling thought that she has done what she could. For among those sleeping heroes her husband, her brother, her father is lying, having given up their lives that "a nation of the people, for the people, and by the people, might not perish from the land."

HANNAH ELIAS

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

It is very unfortunate that such a valuable citizen as Andrew H. Green should be the target for a crazed Negro's revolver, while the real sinner escaped to bring him into nauseating prominence at this late date. How soothing it would have been to Mr. Green's friends, whose confidence in his integrity, no doubt, was somewhat shaken by the manner of his taking off, had this man stood over his coffin and told what he tells now. While I am not in sympathy with Mrs. Elias' manner of living, I believe that others will agree with me that for farsightedness, sagacity and business tact, Hannah Elias is a twentieth century wonder. Nine-tenths of those who are pounding her would, no doubt, like to be as fortunate. Many attractive women are living in luxury at the expense of such old sinners as Platt. His bid for sympathy on the ground that he did not know that the woman was a Negress, is rendered ridiculous by

Page 26

his own statement concerning the visit of his friends from the West who, after being shown the white joints of the Tenderloin, were not satisfied until they had "done the coon joints." A certain class of men are not satisfied in visiting any town North, South, East or West, unless they have paid their respects to the "coon joints." In such a resort, Mr. Platt met Mrs. Elias. He confesses that to his sorrow he lost sight of her, and found her again through an advertisement of massage treatment for rheumatism, by which treatment he was cured. Those of the medical profession will bear me out in the assertion that physicians who command the largest fees are specialists. Mr. Platt, who had rheumatism--a very unpleasant, yet aggrivating malady--had doubtless before meeting Mrs. Elias, spent large sums of money to effect a cure and failed. Mrs. Elias cured him! Such a tormenting disease cured! Should it be wondered at that a rich old man whose life had been thus prolonged, paid handsomely for it, and that he returned frequently for treatment lest the malady return? Is not such a man an ingrate who would seek to beat a poor woman out of the paltry sum of $685,000, which she had earned by performing such a miraculous cure? Was the old gentleman in his right mind when he paid these large fees and gave such handsome presents? Yes. Yes. Then, has he been robbed? No! Mr. Platt is as much against social equality as Mr. Thomas Nelson Page, and is doubtless as opposed to his daughter sitting in close proximity to a Negro woman in a public conveyance. But I don't think he agrees with the Honorable John Temple Graves, that the races should be separated. Suppose we prove that this woman got her wealth dishonestly; is this an excuse for a howling mob about her door? There are men living in that community worth individually from eighty to a hundred millions, and men possessing such wealth have dishonestly gotten other people's money. Is there anybody up there seeking to serve papers on them? Are there howling mobs standing night and day about their premises? For Christian shame! Now Mrs. Elias, who is a wealthy taxpayer, is entitled to police protection, and should have it.

Brooklyn, June 7th, 1904.

Page 27

WORK OF MISSIONARIES

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

I have had the pleasure of reading three installments of Br. Hamlin Abbott's contributions to the Outlook on the Negro problem. Mr. Abbott is, indeed, a logical, instructive and entertaining writer, original in many respects in his way of putting things, and I believe he is earnestly trying to devise some means of settling a perplexing question. But he who reads between the lines may see that Mr. Abbott does not possess sufficient virtue to lift him out of the beaten path and contemplate his fellow citizen from human view point, rather than as a problem that a white man must settle. The disposition to kick the under dog is as old as the human race. I often think of Charles Dickens' story of that wretched boy, Oliver Twist, chased by a wild mob through the streets of London, headed by the real thief, to be "stopped at last," struck down by a coward and dragged off to prison with no one near to pity or protest. I see a lone woman, pursued by a thousand men for over a hundred miles through the swamps and marshes of Mississippi, that they might have the pleasure of seeing her suffer the most shocking death. While in New York, men, women and children to the number of ten thousand seek to tear, as it were, to pieces another, because she had committed the crime of living in luxury. This is the problem, woefully perplexing. I trust that Mr. Abbott may see the wisdom of dropping the threadbare Negro question and give to his readers a few contributions on the more intensely interesting subject, the poor white, the indented slave, the ticket of leave man, over whom the tide of progress has rolled for centuries without making but little impression; the creature that allowed the Negro to break off his shackles and outstrip him in the moral and intellectual and financial race, and actuated by envy, keeps the South in turmoil. Mr. Abbott will find this an almost exhaustless subject. In the dismal fastness of the Gulf States, in the mountainous regions of western North Carolina, east Tennessee, the Virginias and Kentucky can be found material for the turning out of immense volumes of matter as thrilling and

Page 28

interesting as the adventures of "Dare Devil Dick." For there, daily, dramas in real life are enacted that need no stage settings to add to their effectiveness upon the stranger and the unitiated. There, ambushed assassinations are of daily occurrence and vengeance is the law of the land. I would advise Mr. Abbott to visit these sections and write something really interesting. But I would say here that he who would assay to chronicle the doings of these people from the premises is likely to be called from labor to refreshment at any moment. What a ripe field for missionary work? But the missionary will find the work of converting this people more difficult than changing the wildest Patagonian, because they are all Bible-reading heathen--people who can repeat chapter after chapter, who know by heart the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes and attend religious services regularly. Yet out of this great Book, so full of beautiful precepts, they have extracted this one creed--"An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth." There the preacher and the deacon are as quick on the trigger as the meanest moonshiner; there a quarrel over a horse swap or a pig has resulted in feuds that have never ceased until an entire generation has been wiped out. Mr. Abbott is letting pass an opportunity that an angel might covet.

Brooklyn, June 25th, 1904.

SOME COMPARISONS

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

When Rome was mistress of the world, and her barbarian captives were butchered to make holidays, in the vast ampitheatres where these brutal exhibitions took place, women composed a large percentage of the audiences that assembled there to gloat over the sight of human blood. Women were often butchered there, and little babes oft with prayers upon their lips ruthlessly torn to pieces. But we can safely say that in these feasts of blood, women were not executioners, although they were unmoved by the cruel

Page 29

taking off of their own sex. We can therefore rest assured that what took place in a small town in the State of Mississippi a few days ago would have made pagan Rome look aghast and called forth a cry of indignation that would shaken the very temple of the Caesars. In that Mississippi community, before an assemblage of ten thousand people, a child of tender age was made to tie a rope about a man's neck and lead him to his self-appointed executioners, who terrorized the State by their wanton disregard for law and order. The killing of that wretch in this manner was, perhaps, the only way to pacify that perturbed community, but the memory of that awful scene must ever haunt that child, at least until its little heart and conscience have become calloused. There is no question but that these people were wrought up to the highest pitch over the awfulness of the alleged crime; so was King David of Israel over the story told by the prophet Nathan of the rich man who had cruelly taken the poor man's lamb and dressed it for his own guests. "And David's anger was greatly kindled against the man: and he said unto Nathan as the Lord liveth the man that has done this thing shall surely die. And he shall restore the lamb fourfold because he did this thing and because he had no pity. And Nathan said unto David, Thou art the man!" For the King had killed Uriah the Hitite and had taken his wife. Who are these men shouting for virtue and purity? No Negro woman of the South, no Negro child of tender age has as yet been enabled to successfully indict a man of the dominant race who seeks by law and custom to hedge in one woman and destroy another. Why can't these champions consider the various definitions of the term "assault"? The Negro possesses the same propensities of any other creature of the human race, and in the South his environments are such that he cannot with impunity defend his own wife, mother or sweetheart from insult and violence. Now imagine this crowd, intimidated being, running amuck, terrozing communities and making women and children unsafe. These two extremely different traits of character do not exist in a man situated as the Southern Negro. A man is likely to take such liberties where there is most familiarity; where social

Page 30

laws are not so rigidly adhered to, and the man who violates the person of a woman in a community where mere suspicion is death, where to be within close proximity to where a crime of any sort is committed or attempted is death, is irresponsible; and in humane Northern communities would be a subject for expert physicians.

NOT GOOD SOCIETY

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

The recently published interview published in a Manhattan newspaper between an Atlanta correspondent and three returning Negroes to that city from a mob-infested section of Illinois, may not be an unlikely story. It should not be said that the Negro must return South for the very treatment he leaves it to obtain elsewhere. Yet oddily enough, this has been asserted by three men who had tried the North and West. The Southern people should not, however, feel elated over such intelligence, for in return for oceans of stolen sweat, the South should accord the black man better treatment than he even might expect in the North and West. There is no place where a people expect to enjoy every right of citizenship more than in the home they have helped to build and maintain. The South is in the main responsible for the indignities heaped upon the dusky citizen elsewhere, for in return for 250 years of unrequited toil, he has been sent forth with a bad name to be shunned and persecuted by the too credulous Northerner, whose prejudice is kept alive by the far-fetched press reports that precede him. When the Negro has learned the value of a good name, he will then be enabled to appreciate to what extent the Southerner has damned him. "Who steals my purse steals trash." The Negro who regards people who continually malign him as best friends is ignorant of the value of a good name. Negroes differ as materially as do other peoples. We have (as well as the fawning sycophant, satisfied with any form of existence) the Fred Douglas, the Nat Turner, the William Still, to whom freedom with a

Page 31

crust is preferable to wealth in slavery. Such men are today pushing out over the sections of country where most freedom can be obtained, and where the most justice and equity abounds in courts of law, there is most freedom. The arm raised in its own defense is nerved in proportion to the confidence of the individual in the justness and impartiality with which he and his antagonist are to be dealt with in a court of law, Those returning fugitives to Atlanta found this contrast in the North. But if they came North looking for and expecting "social equality" they deserved to be disappointed for their good. That class of whites with which the Negro comes socially in contact in the North and West does him not one particle of good morally, socially, interlectually nor spiritually. The black mother need not boast that her children play with white ones, and that she is the only colored resident in a community. The offspring of the beer besotted parents with whom negro children are thrown in Northern communities no more advance and elevate than the company of wolves, and the mother who thinks that association with such gamins is an advance in the social scale is ignorant and wanting in race pride. The white child whose association would uplift, is as far removed from this class of whites as is the Negro himself. The colored man who comes North feeling that the opportunity to touch glasses at bar-room counters with this class of white men, and to intermarry with women of like calibre, to the disparagement of his own, is a step higher in the social scale, misses the bull's eye by a wide margin.

Brooklyn, August 8th, 1903.

Page 32

COMMENTS ON A REVIEW OF THE "CLANSMAN"

BY THE EAGLE

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

Fictionists and writers of weird tales of carpet-bag rule in the South are determined that the American people shall not forget that regime and the part the Negro played in it. The blunder(?) made by giving the colored man the ballot is to be the Nation's undying worm and unquenched fire. The Eagle's review of Thomas Dixon's new novel, "The Clansman," shows that it is a stronger appeal to race hate and rancor than "The Leopard's Spots," by the same author. What of the Negro and the reconstruction period? Why should much ado be made over his part in that regime? Honest students of history know perfectly well that under the then existing circumstances there was no other course to pursue than to give the Negro the franchise; it was his certificate of manhood, his only safeguard against immediate re-enslavement. Every student of history knows also that the reconstruction period was the natural and inevitable result of war like the War of the Rebellion. Why not go further back and rake those over whose bickerings brought the war on? The Filipino is not charged with rebellion against this country, yet there is a reconstruction period going on in the Philippine Islands. Some day a Filipino Thomas Dixon, Thomas Nelson Page or John Temple Graves will write a story of that period frought with weird and fantastic tales of murder, intimidation, usurpation, tryanny, subjugation, land-grabbing, stealing and mongrelizing. But I guess the book will not be as fascinating to American readers as "The Clansman." Although Mr. Dixon's story begins at Washington, the principal scene of action is South Carolina, and the writer could not have chosen a more fitting scene for a drama of this kind. South Carolina is responsible for the reconstruction period, for that State led off in the rebellion which necessitated such a regime. On the day that the Federal garrison evacuated

Page 33

Fort Sumpter, a little man in a speech to the people of Charleston, said, "This little State has humbled the entire Nation to-day," and pointing to the flag which floated over his head, he continued, "and this little flag now flaunting the breeze over us will in three months' time float over the Capitol at Washington!" Vain boast! If that man could have foreseen what took place during the four years following this incident, he would doubtless have been willing to crawl to Washington to apologize to an insulted Nation. In less than three years half starved and wornout rebel soldiers were cursing South Carolina for having started the disastrous and foolhardy fight. But we Northern sympathisers are inclined to say the South was actuated by the honest convictions that it was right. Why not concede the same to the reconstructionist? Was he not nearer right than the man-stealer?

Brooklyn, January 30th, 1905.

MR. THOMAS DIXON, JR., THE ALIENIST

[The Voice of the Negro, Atlanta, Ga.]

The most interesting and fascinating report of murder trials nowadays is that of the alienist who is generally the prosecuting attorney's most valuable adjunct when circumstantial evidence is the main channel by which conviction is hoped to be secured. While the average newspaper reporter follows closely the proceedings of a trial, notes the evidence of the witnesses, the quarrels of lawyers in their efforts to convict or acquit, the alienist sits by and attempts to open up to the world's gaze the soul of the accused. Every lineament of the features comes under the scrutinizing gaze of the alienist; the eyes, the forehead, the mouth, the chin, the ears, the hands--all of these members are closely studied by this wonderful reader of character and generally arrayed on the side of conviction. For the alienist will show that these carefully studied lineaments evidence weakness--the murder mania, that the crime for which the prisoner stands charged was inevitable. But what a saving it would be to the State and to society if such

Page 34

devils could be singled out and incarcerated before they do incalculable harm. Suppose the expert could discover the weakness of a building, warn his fellows of their danger and thereby prevent the awful calamities that so often take place in our large cities. Such service is done now and then, but successfully determining a person's character by studying the features is not an achievement to be relied upon. Yet, in the great commercial world, the habit of singling out men for certain callings by appearance only has driven many an honest fellow to despair. Thousands of honest men and women are daily turned from places where employment is offered because they cannot pass under the scrutinizing gaze of some expert who presumes to guage their fitness by their personal appearance. There are many honest men with but one suit of clothes which will in time become shabby, look shiny in spite of care; there are sober men and honest men with nothing with which to appear as though they were honest "sober and reliable," who, "turned down," go back to their suffering families with no look of hope, or to end their misery by suicide. Who can successfully read character by either of the above-mentioned mediums? No one! Yet Mr. Thomas Dixon, Jr., has undertaken to do that very thing in an article written in defense of the "Clansman," published in the September number of the Metropolitan, in reply to the following criticism of his latest work in a Boston paper: "He reaches the acme of his sectional passions when he exalts the Ku Kluz Klan into an association of Southern patriots, when he must know, or else be strangely ignorant of American history, that its members were as arrant ruffians, desperadoes and scoundrels as ever went unhanged." This is the verdict of the world that has already passed into history. But Mr. Dixon attempts to set aside this verdict by publishing the pictures of some of the prominent leaders of the Ku Klux Klan and asks the world to forget their awful misdeeds and accept them as paragons of excellence because of the comeliness of their features. In Mr. Dixon's gallery of photographs appears the likeness of Gen. John B. Gordon, of Georgia, General Forrest of Tennessee, Rev. W. W. Landum of Atlanta, Ga.; Hon. John W. Morton of Tennessee.

Page 35

The gentleman has included the likeness of his own father, the Rev. Thomas Dixon, Sr., and unwittingly brands him as a red-handed murderer, a kind of Dr. Jeykel and Mr. Hyde, who could by day preach the Gospel of a loving and forgiving Christ, and at night creep forth in ghastly regalia to assist devils in the work of murder and rapine.

In comparing the likeness of his father with that of Thaddeus Stephens, Mr. Dixon says, "A study of the portrait of Thaddeus Stephens, the man who created the Union League and sent it on its mission of revenge and confiscation, and the face of my father may settle the question as which of two was the desperado in this stirring drama." To further strengthen his defense of the Ku Klux Klan and its dastardly work, the reverend gentleman, in contrast to the handsome likenesses of some of its members, has published the picture of a colored man, "The lowest type of negro, maddened by these wild doctrines, began to grip the throat of the white girl with his black claws. The bestial looking creature whose portrait accompanies this article is a photograph of this type from life. It appeared in the first editon of my novel, 'The Leopard's Spots,' but the publishers were compelled to cut it out of all subsequent editions, because Northern readers could not endure to look upon the face of such a thing, even in a picture." And yet we come across or meet just such looking men in our every day life in Northern cities; they are the trusted butlers, coachmen and men of all work in nearly every aristocratic Southern home. Northern women who went South just after the war went about unmolested, and such women are still going about unmolested among such "things." In the month of July, while in the city of Philadelpha, I attended services one Sunday morning at the Wesley Methodist Church and listened to an eloquent sermon by an eminent Christian minister with just such a looking face as appears in Mr. Dixon's article. Doubtless no sweeter soul lived than reposed beneath that ebony skin, and no provocation however strong could induce this homely disciple, made in the image of his Maker, to stoop to perform the knavish work which Mr. Dixon boasts his father performed.

Page 36

TAKES ISSUE WITH THOMAS NELSON PAGE

AND THE REV. MR. DIXON

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

Now that Mr. Thomas Nelson Page has written the last installment of his very interesting study of the Race problem, the question uppermost in my mind, as I ponder over the closing article before me, is, would Mr. Page lift a finger to remove one of the defects in the race he has so glaringly enumerated? Would not Thomas Nelson Page resist with all the strength of his manhood any attempt on the part of friend or foe to open the closet of the Southern home that the skeleton which hides there might stalk forth in all of its ugliness? Yes! a thousand times Yes! An attempt at such a thing on the part of an editor in Memphis, Tenn., some years ago, resulted in the demolishing of his entire plant. Another such attempt at Wilmington, N. C., in 1898, resulted in the wild hunt for a fugitive in seven States. Looking at the situation from this viewpoint, Mr. Page occupies the positon of a giant in armor striking at a pigmy. If such an attack upon a neighbor and benefactor is Mr. Page's version of Southern chivalry and manhood, let us build a monument to Judas Iscariot and compose anthems of praise to Benedict Arnold. Emerging slightly from the beaten path, Mr. Page divides the Negro race into three classes, i. e., the respectable, the middling respectable and the very bad. He could have done much in the way of assisting that respectable element by using his pen in an assault upon the law just passed in the State of Virginia, which places such a woman as Mrs. Booker T. Washington on a level with the lowest of bad women. The gentleman reluctantly admits that the Negro has been an indespensible adjunct--a potent factor in building and maintaining this republic, and yet he would deprive him from breathing the air he has helped to free and purify. To put a little more than 3,500,000 blacks in this country it cost Africa 40,000,000 human lives by butchery, starvation and drowning. A trail of blood followed the slave ships from Africa's shores to the American coast. Should not the penalty for such a horror be a more perplexing problem? As

Page 37

is not the case with the white race, Mr. Page asserts that education does not improve the Negro's morals. He is a very low being. But listen to an attack from the mouth of the Rev. Mr. Dixon from quite another and unexpected source, in a sermon delivered in a certain Brooklyn theatre, Sunday, May 8th. He said: "There are villages in New England to-day without a religious service from January until December, except an occasional funeral service, where the Sabbath is no more regarded than by Judge Gaynor here, and where marriage is scarcely more regarded than by the people in the heart of Africa. The people have drifted, not into infidelity, but into licentiousness and sin upon sin, and they are learned and cultured," etc. These are white people, and the same may exist in Mr. Page's neighborhood, but he hasn't the courage to say it, neither has Rev. Dixon, who is a Southerner. Not many years ago in a Virginia city, a Negro man and a white woman agreed to marry, and in order to avoid trouble, went to Washington, married there and returned. But these two honest people were arrested, tried and sentenced each to five years in prison, and the judge in sentencing them gave them a long and severe lecture on ethics. And yet that very judge maintained a Negro woman with six mulatto children within two blocks of his home. Most learned judge! Most excellent exponent of ethics! He was a white man! This Negro woman was the leper to be shunned. It's a great thing to be a white man; it sugars over the grossest sins and vineers the roughest exteriors. No wonder ignorant, renegade Negroes are clamoring for face bleach.

Page 38

JACK THORNE UTTERS A BLAST FOR MANLINESS

To the Editor of "The Brooklyn Eagle":

When a few evenings ago I listened to an address by a member of the Afro-American Business League, before the Literary Society of the Carlton Avenue Branch of the Y. M. C. A., on his recent visit South, I remarked at its conclusion that comments on the material advancement of the Southern Negro in consequence of the general denial of the franchise, should not be indulged in by our leaders as a reason why he should eschew politics. But what I said was not favorably received by the audience, who was misled by the fierce retort of the speaker, who held that politics was a bane to the progress of the Southern man of color. I hold, however, that if the ballot is not good for the Negro, it is not good for the white man. If it is not good for the ignorant, it is not good for the learned. If it is not good for the poor it is not good for the rich. But I refrained from prolonging the argument. A few days since a published interview had with this gentleman by a Brooklyn paper's representative, relative to his Southern trip, has been handed me by an indignant citizen, with a request that I answer it. Our friend says that he stopped at many points (going South) long enough to acquire information on the condition of the Negro and the relations between the two races. He looked and listened in vain, he said, for encouragement. "But passing through the South this way, one is confronted with the worst phase of the problem(?) because the stations and depots are the centers of the slothful, vicious and ignorant class of Negroes." The gentleman saw more in Atlanta to be ashamed of than proud of, "for the worst of the race is in the majority and more in evidence, and the race is judged in the South by its worst side. So long as the self-respecting Negroes are in the minority, the slothful, vicious Negroes will be mill-stones about their necks." Too bad! Too bad, indeed! The Southern Negro is noted for his humble manners, generosity

Page 39

and hospitality, looking for the best in the storehouse to put before the stranger, and I am a witness to the fact that for preparing nice, juicy, tender, fried chicken, all done up in batter, the Southern Negro is peculiar. Now who is that so base and ungrateful as to rise from a table where such delicious victuals are served and "backbite" the neighbor who prepares it? We are, indeed, sorry that this gentleman could not return to the North with something more original and interesting to talk about. The white man, when he returns from the South, usually returns Southern hospitality by publicly saying something to please them, and nothing is more pleasing to the average Southerner than expressed sympathy for him in his very unpleasant environments (all his own making) and a tirade against the Negro. The late Miss Frances Willard, on her return from a lengthy stay in the South, publicly thanked her Southern hosts by saying in a magazine article, "I pity the Southern people. The Negroes are swarming like locusts in Egypt, and the white man dare not leave the threshold of his own door," etc. A more malicious falsehood was never uttered against a defenceless people. The white man can leave the threshold of his door, and does leave it to cross that of the black man to scatter shame and ignominy, which he can do with impunity. Now why didn't the gentleman follow this example and kick the other fellow? When a few years ago ex-Gov. Northen of Georgia invaded Boston armed with a typewritten defence of the burning of Sam Hose, the Congregational Club of that city paid two dollars a ticket to hear an African Methodist bishop refute the charges made by the Georgian against his people and defend them. The members of that club and their friends listened in disgust to a crawling Negro who joined Northen in his tirade of abuse. "Thou too Brutus?" That very bishop is supported in luxury by those low(?), vicious(?) Negroes, whom he was not man enough to defend, and they should repay him by cutting off his meal check.

Now our friend could have given us more interesting talk had he scoured around Atlanta and made a study of the low whites of that section, for God has not created a

Page 40