Before the War, and After the Union.

An Autobiography:

Electronic Edition.

Aleckson, Sam (Samuel Williams), 1852-c.1945

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Tom Horan and Bethany Ronnberg

Images scanned by

Chris Hill

Text encoded by

Chris Hill and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 200K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

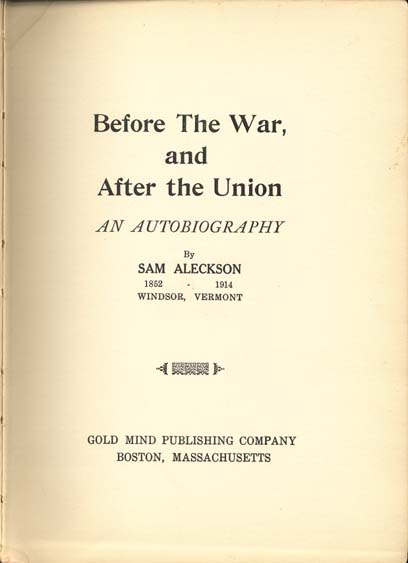

(title page) Before the War, and After the Union; An Autobiography

(cover) Before the War, and After the Union

Sam Aleckson (Samuel Williams)

171 p., ill.

Boston, Massachusetts

Gold Mind Publishing Company

[1929]

Call number E185.97 .A36 1929 (Cornell University Library)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Slaves' writings, American -- South Carolina.

- Plantation life -- South Carolina -- History -- 19th century.

- South Carolina -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865.

- Reconstruction (U.S. history, 1865-1877) -- South Carolina.

- Slavery -- South Carolina -- Charleston -- History -- 19th century.

- African Americans -- South Carolina -- Charleston -- Biography.

- Aleckson, Sam, b. 1852.

- Slaves -- South Carolina -- Charleston -- Biography.

Revision History:

- 2000-12-12,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-03-29,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-03-23,

Chris Hill

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-03-17,

Bethany Ronnberg and Tom Horan

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

Before The War,

and

After the Union

An Autobiography

By

SAM ALECKSON (Samuel Williams)

1852--1914

WINDSOR, VERMONT

GOLD MIND PUBLISHING COMPANY

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

Page verso

Copyrighted 1929

SAMUEL WILLIAMS

Printed in U. S. A.

GOLD MIND PRINTERS

Boston, Mass.

Page 7

"I will a plain unvarnished tale deliver."

Shakespeare.

Page 8

BEFORE THE WAR

- 1 Genealogy . . . . . 17

- 2 Childhood . . . . . 22

- 3 The Fickle Maiden . . . . . 35

- 4 The Lover . . . . . 61

- 5 The Hunting Season at Pinetop . . . . . 66

- 6 The Beginning of the End . . . . . 76

- 7 In Town Again . . . . . 86

- 8 A Turkey Stew . . . . . 94

- 9 Tom Bale . . . . . 98

- 10 Silla--The Maid . . . . . 108

- 11 The Appraisement . . . . . 113

- 12 The Big Fire . . . . . 117

- 13 Mr. Ward's Return to Pinetop . . . . . 119

- 14 Roast Possum . . . . . 128

- 15 After De Union . . . . . 138

- 16 In the Land of the Puritans . . . . . 147

- 17 The Town of Springlake . . . . . 155

- 18 Wrong Impressions . . . . . 165

CONTENTS

Page 11

Dedicated

to

My Children

and

Grand Children

Whose

Kindness and Affection

Serve in Great Measure

to Make My Declining Years

Peaceful and Contented.

Page 14

PREFACE

"When I began this unpretentious narrative, I was almost sightless. I had just recovered from a severe attack of illness, during which for a time I became totally blind, and after I was better my eyes seemed hopelessly affected. This I endeavored to conceal as I had to earn my bread, but so frequently did I pass my most intimate friends on the street without the slightest show of recognition that I was forced to admit I was almost blind. I was then urged to consult an eminent physician of the town who gave special attention to ailments of the eye, and after a complete examination, he informed me that my eyes were in such condition that glasses would do me no good, and with a show of sincere sympathy said, "I am sorry for you, but within six months you will be totally blind."

"Approaching blindness is always appalling, especially to one who is dependent on his labor for a living. 'What shall I do when my sight is gone?' This question forced itself upon me night and day. I was then past middle life, and the prospects of a blind and helpless old age stood out before me. My life had not been wholly uneventful; I had been of

Page 15

an observant turn of mind from my youth. What if I could set down the events that had come under my observation in some connected form? Might I not thereby be able to earn something toward my support when I could no longer see!

"I was compelled to give up some of my work on account of failing sight, but I was still employed by day. I began to write at night often tinder poor light, being scarcely able to see the words as I traced them. Thus my MS. was finished. Untoward conditions prevented publication and it has lain hidden away all these years. The motive that first prompted me to undertake the task no longer exists, my sight has been providentially restored, and at the age of seventy-two I find myself in good health and able to earn my living. There are other considerations, however, which actuate me, even at this late day, to present to the reader this crude story.

"It is a remarkable fact that very many of the immediate descendants of those who passed through the trying ordeal of American slavery know nothing of the hardships through which their fathers came. Some reason for this may be found in the fact that

Page 16

those fathers hated to harrow the minds of their children by the recital of their cruel experiences of those dark days. There is, however, a deeper reason. It is found in the religious nature of the Negro and the readiness with which he fell under the influence of Christianity, and the zeal with which he strove to follow the teaching and example of the lowly Nazarene.

"If the Negro had emerged from slavery in a sullen and vindictive frame of mind, he would unquestionably have shared the fate of the American Indian, and we would not now be witnessing the marvelous progress he is making, nor his surprising increase in numbers.

"While it is sweet to forgive and forget, there are somethings that should never be forgotten. If this humble narrative will serve to cause the youth of my people to take a glance backward, the object of the writer will have been attained. As Frederick Douglass has said, "How can we tell the distance we have come except we note the point from which we started?"

Page 17

CHAPTER I

GENEALOGY

"Breathes there a man with soul so dead"

I WAS born in Charleston, South Carolina in the year, 1852. The place of my birth and the conditions under which I was born are matters over which, of course, I had no control. If I had, I should have altered the conditions, but I should not have changed the place; for it is a grand old city, and I have always felt proud of my citizenship. My father and my grandfather were born there, and there they died--my grandfather at the age of seventy-two, my father at seventy-six. My great grandfather came, or rather was brought, from Africa. It is said he bore the distinguishing marks of royalty on his person and was a fine looking man--fine looking for a Negro I believe is the

Page 18

usual qualification--at least that is what an old lady once told my own father who had inherited the good looks of his grandsire.

I do not know the name my great grandfather bore in Africa, but when he arrived in this country he was given the name, Clement, and when he found he needed a surname-- something he was not accustomed to in his native land--he borrowed that of the man who bought him. It is a very good name, and as we have held the same for more than a hundred and fifty years, without change or alteration, I think, therefore, we are legally entitled to it. His descendants up to the close of the Civil War, seemed with rare good fortune under the Providence of God, to have escaped many of the more cruel hardships incident to American slavery.

I may be permitted to add that on the arrival of my progenitor in this country he was not allowed to enter into negotiation with the Indians, and thereby acquire a large tract of land. Instead, an axe was placed in his hands and he therefore became in some sort, a pioneer of American civilization.

Page 19

My father and my mother were both under the "yoke", but were held by different families. They made their home with my father's people who were, of all slave holders, the very best; and it was here that I spent the first years of my life.

My mother went to her work early each morning, and came home after the day's work was done. My brother, older than I, accompanied her, but I being too young to be of practical service, was left to the care of my grandmother--and what a dear old christian she was! At this time her advanced age and past faithful service, rendered her required duties light, so that she had ample time to care for me. Her patient endeavor to impress upon my youthful mind the simple principles of a christian life shall never be forgotten, and I trust her efforts have not been altogether in vain. She was born in the hands of the family where she passed her entire life; and it would be a revelation to many of the present day to know to what extent her counsel and advice was sought and heeded by the household--white and black.

Our household was large; beside the owners, three

Page 20

maiden ladies (sisters) there were a dozen servants, some like my father, worked out and paid wages, but all:

"Claimed kindred here

And had their claims allowed."

for, there never was a better ordered establishment, nor were

there ever better examples of christian womanhood than that

of the three ladies who presided over it; and it is especially

worthy of note that all the servants who were old enough,

could read, and some of them had mastered the three "R's",

having been taught by these ladies or their predecessors.

Before the beginning of the Civil War these kind ladies

liberated all their slaves, and it is no reflection on the Negro

that many of the liberated ones refused to leave them. There

were many considerations that prompted them to decline

their proffered freedom; in some cases husband and wife

were not fellow-servants, and one was unwilling to leave the

other. All those who accepted their liberty were sent to

Liberia. I know of one who returned after the, war to visit

relatives and friends. He had been

Page 21

quite successful in his new home, and he gave good account of those who had left Charleston with him. Some had died, others were doing well. He found one of the good ladies still living and had the great pleasure of relating his story to her. When, after a brief stay in the city, he took his departure, he carried with him many tokens of remembrance from their kind benefactress for himself and those at home.

Page 22

CHAPTER II

CHILDHOOD

"How dear to my heart are the scenes of my

childhood

When fond recollections present them to view."

Though fifty years of time and more than a thousand miles of space separate me from the home of my birth and early childhood, the old home seems more plain before me now than places I visited but yesterday. It was a grand old house, built of grey brick. There were three spacious piazzas running along the west and south sides of the house. The wide yard was paved with brick. To the west of the paved yard was a large garden in which rarest flowers bloomed; but dearer than all to our youthful hearts were the "Four-o'clocks", that grew there in great profusion and various colors. We made festoons of them, hung them over our heads while we

Page 23

"played house" and made mud pies beneath. We wove garlands and twined them about the neck of dear old "Watch." He was our great Newfoundland. Was there ever such a faithful dog as he? Noble animal, rough and tumble with the boys, gentle with the girls, but kind to all. The bulldog and the pug have taken his place now, but surely there never was a safer or kinder friend to children than he. Our "Watch" had never read "The Rights of the Child," but he put his foot, or rather his paw (no small one), down on any of us being punished in his presence. Whenever our parents deemed it encumbent on them to give forcible and painful evidence that they were not amendable to the charge of "sparing the rod and spoiling the child," it was necessary to lock Watch up in the woodshed, and if in their haste this precaution was neglected he would rush in, seize the slipper or strap (they used both in those days), between his teeth and hang on like grim death. After we had escaped to the yard he would run out, lick our faces and seem to say, "I told you I would not allow it. Come, let us have a romp."

There were fruit trees in our garden; peaches,

Page 24

apricots, pomegranate and figs. We loved the figs most, of which there were several varieties. Our especial pride was the large black fig tree. There were six of us, three girls and three boys. Four of us were white and two were Negroes. Did we quarrel and fight? No indeed! Our little misunderstandings were settled long before we came to blows. There was more of the spirit as well as the letter of the little lines:

"Let dogs delight

To bark and bite,"

than seems generally the case now. Would there

was more of that spirit abroad in the land today

then would we hear less of Negro problems,

deportations, and the like.

Every morning in season would find us at our favorite fig tree. The, boys would climb into its branches while the girls stood below with extended aprons to catch the fruit as we dropped them. Some times there came a voice from above in complaining tones--"Now Jennie! I see you eating." "Oh," would be the reply, "That one was all mashed up." "All right, now don't eat till we come down."

Page 25

Then when we descended we took large green fig-leaves, placed them in a basket, laid the most perfect fruit thereon, and one of us would run to the house with it. . . . "Don't eat till I come back." "We won't." . . . When the messenger returned we went to our favorite nook in the garden and after dispatching about a dozen figs apiece we rushed to our breakfast with appetites as unappeased as if we had fasted for a week--And then to school, "But not the Negroes" you say? Yes indeed! The Negroes too.

The four white children that formed a part of this little band did not live at our house. They were niece and nephew of our good ladies and lived a short distance from us. They came regularly every morning and afternoon, except Sunday, to "play in our yard." They attended a private school, while Jennie and myself, the two Negroes, were taught at home by their aunts for two or three hours each day. One of these kind ladies, usually Miss S----, strove with our obtuseness. We had only one book each, but it was a great book. I thought so then and I think so now. From it, like all great men, we first

Page 26

learned our A B C's, then came A-b-âb B-a, ba and so on to such hard words as ac-com-mo-da-tion, com-pen-sa-tion and the like. From this wonderful book we learned to read, write, and cipher, too. We also got an idea of grammar, of weights and measures, etc. We had slates, for those useful articles had not yet gone out of fashion.

There were pictures in our book illustrating fables that taught good moral lessons, such as that of the man who prayed to Hercules to take his wagon out of the mire; of the two men who stole a piece of meat; of the lazy maids and of the kindhearted man who took a half frozen serpent into his house. This book was called, "Thomas Dilworth's," and many a slave was severely punished for being found with a copy of it in his hands. When one had succeeded in mastering the contents of this book (which they frequently did), he was considered a prodigy of learning by his fellows. I do not know whether Mr. Dilworth has ever had a monument erected to his memory, but if ever a man deserved one it is he.

This was a Christian household. The Sabbath

Page 27

was strictly observed. Duties were reduced to the barest necessities, and all attended church. There was no cooking. Cold meats, tea and bread served to satisfy our hunger on the Lord's Day. The ladies were Congregationalists and attended the "Circular Church." The servants were left to their own choice in religious matters and were divided in their religious opinions. My grandmother was a Methodist and attended "Old Cumberland." It required something very serious to prevent the dear old lady going to prayer meeting on Sunday mornings. These meetings were held at an early hour, but I always went with her. Each one entered the sacred place in solemn silence. When the moment arrived some leader would raise one of those grand old hymns such as--

"Early my God without delay

I haste to seek thy face."

for, they sorely felt the need of Him who

Page 28

"Tempereth the wind to the shorn lamb!" Then at the close they sang--

"My friends I bid you all farewell

I leave you in God's care

And if I never more see you,

Go on, I'll meet you there."

It not only had reference to the final dissolution, but also

to the uncertain temporal condition under which they lived,

for, in many instances before the next prayer meeting they

were sold, to serve new masters in distant parts. Often

without having time to say good-bye to relatives or friends.

When meeting was over they filed out quietly. No buzz of voices was heard until they reached the sidewalk. Then, after a hearty handshake and a word of cheer and hope, they hastened to their duties; many to serve hard and impatient masters. 'Twere well for these that they had been fortified by those few moments of prayer and meditation.

The people showed commendable zeal in attending these meetings. In those early Sunday mornings men and women might have been seen standing within their gates. They appeared to be listening

Page 29

intently, as if to catch some sound (for they must not be found on the streets after "drum beat" at night or before that hour in the morning). At the first tap they hastened out to their respective places of worship, there to lift up their hearts and voices in prayer and supplication to God.

My mother's people too, were of the "St. Clair" type. On Sundays after Sabbath School I was permitted to visit my mother at their home. They were Mrs. Dane, a widow, and three grown children--a daughter and two sons. The daughter was married. The sons, Thomas and Edward were unmarried. I always looked forward to these visits with pleasure as I was sure to be regaled with lumps of sugar and pieces of money, by the old lady and the other members of the family. Besides, Mr. Edward (who was a lover of fine horses, and of whom I shall have something more to say later), would treat me to a horseback ride around the large lot.

There is nothing good to be said of American slavery. I know it is sometimes customary to speak of its bright and its dark sides. I am not prepared to admit that it had any bright sides, unless it was

Page 30

the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln . . . There was often a strong manifestation of sympathy, however. A sad incident which occurred in the Dane family when I was about eight years old may serve to illustrate this:--It was usual in those days for each member of a family to have his or her own personal attendant. Mr. Thomas Dane, a kind-hearted gentleman of studious habits and quiet demeanor, had as his servant, a woman called Beck. He did not take breakfast with the family. It was his custom to take his morning meal in his own apartment being waited on by her. Like all the good slaveholders the Danes did not ruthlessly sell their slaves. I do not know how it came about that two of Aunt Beck's children had been sold. She had one remaining child at this time. He was a bright fellow of about sixteen years of age. He was well-liked by all on account of his cheerful disposition. I cannot tell the cause of it, but the boy George was sold away from his mother as had been his brother and sister. This was a heavy blow to her. One morning, shortly after the sale of George, Mr. Dane came down to

Page 31

breakfast. Noticing the dejected appearance of his servant, and no doubt, discerning the cause he ventured some pleasant remark, but Aunt Beck's heart was heavy. At last, no longer able to suppress her great grief she began to weep. "My last chile gone now, Mas' Thomas," she said.

"I know it Beck," he answered, placing his hand to his head, "But, my God! I could not help it."

He rose from the table and paced the floor. The woman became alarmed at the agitation of her master, and forgetting her sorrow for the moment, said, "I know you couldn't help it Mas' Thomas. Sit down and eat your breakfast."

But, no breakfast for him that morning. Presently he went up to his room. Soon he returned having arranged his toilet with more than usual care. He stepped out into the yard, entered an outer building--in a moment a pistol shot was heard! They rushed to the step, but his life blood was ebbing away. He never spoke again. The grief of the woman was more than he could stand.

I visited the place a few years ago. There were different people there. They knew naught of that

Page 32

sad tragedy, nor did they know that Petigrue, Rutledge, Horry, Pringle and Lowndes were once regular visitors here. The old house and its surroundings are very much as they were fifty years ago. The chimes of St. Michael can still be distinctly heard and the hands on the dial may still be seen from the house.

It is quite different at the place where I was born. There is not a vestige of the old house to be seen, for a great fire since that time, swept over this district and destroyed it and nearly every nearby dwelling house. In my childhood we had as near neighbors Pinckney, Legare, and Prescott. There is nothing about the locality now to show that here was once the abode of aristocracy and wealth, for, in no instance have the old families rebuilt their homes here. Very near our house stood a large and quaint old dwelling built before the Revolution. The front door was reached by high flights of steps. I always stood in awe of that house; partly because of the high wall that surrounded it, and partly because once a member of the tribe of "Weary Willies," chanced to pass that way, He sat down on those

Page 33

steps to eat a loaf of bread that had been given him. Whether from hunger or from some other cause, (I never knew), he died there with the bread in his hand. As a result, "Go die on Blank's steps" became a phrase of the day. The wall that surrounded that old place was high--higher than any wall appears to me now. It was ornamented on top with glass bottles--broken bottles. The man who broke them seemed to have had murder in his heart. He did not follow any particular line in breaking them, nor did he seem to strive at color effect. There were white, black and brown bottles all broken in a way that was calculated to inflict mortal injury on any who attempted to climb into the inclosure.

But the old house and its high wall too have disappeared. Cotton yards and ware-houses now occupy the site of many an old mansion. Houses have been built on some of the lots, but they are far less pretentious than their predecessors, and are occupied by different people. For--

"Other men our fields will till

And other men our places fill

A hundred years to come."

Page 34

There were many walls like the one I alluded to in the quaint old city, but they have nearly all disappeared. All the midnight prowler has to do now is to step lightly over artistically trimmed hedges and meander through beautifully laid out walks to the rear of the premises to where the feathery tribe reposes in ornamental structures. But if the glass bottles and high walls are no more, the dim flickering street-lamps' have also been replaced by the brilliant electric light, thus enabling the watchful owner to place his "Mustard seed" the more accurately where they would do the most good. Therefore, . . . The "Knight of the feather" may well sigh for the good old "lamp oil" times.

Page 35

CHAPTER III

THE FICKLE MAIDEN

"We will ring the chorus

From Atlanta to the sea."

MY mother and her children fell to the lot of Edward Dane, brother of Thomas. This young gentleman was of a gay disposition; fond of horses and the sports of the day. Like his brother he was kind and generous. He taught me to ride, and when I could sit my horse well "bare-back" he had a saddle made for me at the then famous "McKinzie's" saddlery, sign of the "White Horse at the corner of Church and Chalmers street. (Gentlemen had their saddles made to order in those days). I would often accompany him "up the road" on horseback to the Clubhouse, there to exhibit my youthful feats of horsemanship, for the divertissement of Mr. Dane and his friends. My horse, Agile and myself were the best of friends. He never hesitated at a hurdle

Page 36

and we never had a mishap. Possibly Mr. Dane had "views", concerning me for he owned several fast horses, but before I was old enough to be of practical service, "Sherman came marching through Georgia."

Here I shall have to admit that I was a "Sherman Cutloose" (this was a term applied in derision by Some of the Negroes who were free before the war,-- To those who were freed by the war). I am Persuaded however that all the Negroes in the slave belt, And some of the white men too, were "Cutloose" by General Sherman. But let bygones be bygones. "We are brothers all, at least we would be if it were not for the demagogues and the Apostles of hate.

Mr. Edward Dane was an ardent supporter of the "Code." He was an authority on such matters and could arrange a meeting with all the nice attention to details that characterized gentlemen of the "Old School" in South Carolina. His deliberation in such Matters would have been a keen disappointment to "Mr. Winkle" as there was never was any danger of the police or anyone else interfering when he had matters in hand. The police, however, never interfered

Page 37

with gentlemen of the "old school" in the "Palmetto" state. The following story is told of a well-known gentleman of a past generation:--He was a man of splendid physique and dignified carriage. One morning he entered the Old Charleston Market with a lit cigar between his lips. Soon he was accosted by a policeman, a new recruit from the Emerald Isle. "It be aginst the law to be afther schmokin in the Market, Sor," he said. "The law," said Mr.----. "I am the law. When you see me you see the law. The law was made for poor white men and Negroes." And he strode on leaving that son of Erin a wiser, if not a better man.

The Danes were society people. In their well-appointed home they kept many servants, Mrs. Dane and her daughter Mrs. Turner were both kind ladies. The old lady had a way of personally looking into matters about the establishment that secured for her a pet name from the servants. Whenever she started on her tour of inspection word would be passed along, "de old Jay comin'. This would send every one to their post of duty. Of course the servants were ignorant of the fact that

Page 38

Mrs. Dane knew anything about the re-christening she had secured at their hands. Judge of their surprise therefore, then that lady presented herself before them and announced, "Yes, here comes the 'Old Jay!'"

They were all assembled in the kitchen for a little chat, and their attitudes and the expressions of bewilderment on their faces would have delighted the heart of an artist. The cook was just about to emphasize a remark he had made by bringing a large spoon which he held above his head down on the dresser, when the sudden appearance of the lady and her words, seemed to arrest the descent. There he stood in open-mouthed amazement. Mrs. Dane surveyed the scene for a moment, then quietly withdrew, a smile of amusement on her face. This incident was long remembered by those present, but any reference to it in his presence was promptly frowned down by the Cook, who felt keenly the ludicrousness of the figure he cut with the uplifted spoon. It was a much as their dinner was worth for any one of them even to raise a spoon above their heads.

Page 39

Uncle Renty, the cook, particularly disliked these periodical intrusions in his domain. The altogether unnecessary clatter and clashing of pans and kettles whenever the lady made her appearance was only his method of expressing his resentment. This, Mrs. Dane well understood, and never prolonged her stay in the kitchen, for the old man's ability as an artist in his profession was recognized and appreciated. It was said that when the elder Mr. Dane was alive, he frequently began and ended his dinner with one of Uncle Renty's soups. They were simply marvelous, especially his turtle, calf's head and okra soups. How he made them no one knew, nor would they have been any wiser if he had been questioned on the subject. He had several dishes of his own invention to which he had given original names. The other servants had great respect for him; the old, because of his skill, and the young, because of his readiness with the rolling pin. He had obtained the name of "Old Scarlet" from his follow-servants. But those who ventured to call him so always took pains to get out of reach. This is how he got the name:--

Page 40

In those days personal application for work were frequently made from door to door by the "newly arrived." One day an Irish woman applied to Mrs. Dane. She did not need her particularly, but thought she might give the woman work for a day or two as assistant to Uncle Renty, for they were to have a large dinner party:--"Wait a moment," she said. The lady knew the old man well enough to know that diplomacy was required. Going to the kitchen she complimented him on the neat appearance of things. "You are all in readiness for the dinner I see."

"Yes ma'am." (Now the old man had already been apprised of the purport of her visit. He was fully prepared. He was by no means color blind, but was not well posted in the nomenclature of colors.)

"And do you know daddy Renty," continued Mrs. Dane, "I have thought that you might need some additional help in the kitchen for a day or so."

"Everything was all right las time, ain't ee ma'am?"

Page 41

"Oh yes, certainly. Everything was just splendid," she replied, "But a white woman has applied to me for work and I thought--."

"Mis Charlotte," interrupted Renty, "I don't car if she white as scarlet, ma'am, I doan want um in my kitchen." Argument was useless and so a job had to be found for Bridget in the laundry.

But all of this was before the untimely death of Mr. Thomas Dane, to which I referred in the preceding chapter. That sad event seemed to have been the beginning of trouble for the Dane family. Indeed things were becoming serious for all. The probability of war between the states was manifested more and more daily. There was a growing feeling of unrest everywhere, and it was soon known that this calamity would not be averted.

The very commencement of the war seemed to have brought disaster to the financial prosperity of many, and the Danes were among the earliest to feel its effects. Some of the servants were sent out to work and so it happened that my mother went as cook for a wealthy family in the city. They were very kind people. Mrs. Bale was a widow with two

Page 42

children. They were both married. Mrs. Ward, the daughter, and her husband lived with her mother. The son, Tom Bale had establishments of his own.

It was hard for me to leave our dear old home at the Misses Jayne's, my father's people, for there was my good old grandmother, the kind ladies, my playmates and faithful old Watch. But the distance was too far for my mother to walk back and forth, (there were no street cars in those days), so we had to make our home at Mrs. Bale's house. I found some consolation however, in our new home. Mrs. Ward had two boys, and they and I soon became good friends. Besides, there were horses there, and Uncle Ben, the coachman allowed me to Ride them to water. There were children living next door too, with whom I became acquainted, and this led to a romantic incident in my life years afterward. When "the Union had come in," I married one of the little girls who lived next door, although I had to go all the way to New York to find her.

Our stay at Mrs. Bale's was very pleasant, circumstances being considered. It was here, however

Page 43

that I witnessed the first instance of cruelty or harshness of an owner to his slave that ever came under my personal observation. Of this I shall have more to say. I missed my weekly visits to the Danes too, for besides the pennies, lumps of sugar and horseback rides, I had many friends there also. Then there was Cora, the daughter of one of the servants, I am still inclined to believe that she was the most beautiful girl I have ever seen. She was endowed with an olive complexion, large black dreamy eyes, raven hair, pearly white teeth and a bewitching smile. Her voice was one of the most unusual voices I have ever heard. Cora used to kiss me and call me her little sweetheart, (for though you would not believe it now, then I was a bright-looking little two-headed chap, and got many a kiss from the "big girls" in the neighborhood, because they said I was so cute.) But that was years and years ago. Cora promised to "Wait for me." Of course I believed her. She was eighteen and I was about nine years old, yet I thought that somewhere in the race of life I would overtake her and she would be mine. It never occurred to me that when I had

Page 44

reached eighteen she would be twenty-seven, and the disparity in our ages would be the same. Years afterward I met her. She was married and had several children, while I was just entering into young manhood. How fickle some girls are, eh?

There was a large garden with fig trees and flowers in it at Mrs. Bale's house, but the figs were not as sweet nor were the flowers half as beautiful as those at my old home. There were two dogs not near so clever as our Watch, and the children--well, they had never lived at a home like our old place on Guignard Street. In fact, there never was another home like that, but "Grief sits light on youthful hearts." All my regrets were greatly modified by the prospects of a visit to the country. Such a trip always seems alluring to a city boy. Indeed the country seems to hold out allurements to everyone except those who live there. Mr. Ward owned a plantation to which the family went every winter, and when it became known to me that we were soon to go there, I was all impatience. I plied Uncle Ben with a thousand questions as to how far away it was, what kind of a place, what was to be seen,

Page 45

were there any snakes, did they bite, was there any wild horse running about in the woods, did he think I might catch one? Etc., etc. Now Uncle Ben was a philosopher. He was not given over much to talking. No one but myself would have dared to ask him so many questions. He had taken a fancy to me. Everyone said it was a wonder. He had no children of his own, besides he was inclined to be somewhat of a misanthropist. I would sometime have to wait indefinitely for an answer to a very simple question. However, by the exercise of patience and discretion I finally got all the information I desired, or thought I did, which amounted to the same thing.

Uncle Ben was epigrammatic as well as philosophical. one night after a very trying day he went to prayer meeting. He was feeling rather blue, and did not intend to take an active part in the exercises. Of course the conductor of the meeting knew nothing of the old man's frame of mind. "Will brudder Ben jine us in prayer?" he asked, but there was no response. "I mean brudder Ben Bale," he said, fearing there might be some misunderstanding. Being thus importuned the old man knelt down and delivered himself as follows:-- "A ha'd bone to caw. A

Page 46

bitter pill to swoller." Bress de Lawd. Amen.

But Christmas was approaching, and Santa Claus was gleefully expected for the good old man was a real personage in those days--not a myth. Oh, but you say it was wrong to deceive the children, as it had a bad effect on them? I don't know, but it seems to me that the children who believed in Santa Claus in those days would at least compare favorably in their love of truth with those of the present day who know, "It is only father and mother." At all events the country was forgotten for a while. It was sometime after holidays that we left for the plantation. There was not a gayer boy than myself when we boarded the train. (This was in the year 1860).

When we arrived at the station there were three teams awaiting us; one for the family, one for the servants, and another for the baggage. Uncle Ben was there, having brought the horses up by road a few days before. I rode on the baggage wagon. As there were only the driver and myself on it I thought I could ply the former for information without being requested to "Hold my tongue," an operation

Page 47

that I had always found difficult. My companion I found was I well grown boy whose name was Missouri. Why they gave him that name I do not know. Perhaps it was in honor of the "Missouri Compromise." He said his name was the same as that of a great country miles and miles away, that he was called "Zury" for short, that his principal work on the plantation was plowing, and that his mule, Jack, was the best plow animal on the place. He also informed me that there were a large number of children on the plantation whose work was to play, and to keep the rice birds out of the fields. I suppose he was thoroughly dry by the time we got To "Pine Top," but he was a good-natured follow. We became firm friends. I always rode his mule from the field to the barn. Zury is now living in Charleston, where he is a successful mechanic known as Mr. Ladson.

Anyone visiting the old time plantation must have been impressed by the boundless hospitality of the people. Everybody came to see us. They brought chickens, eggs, potatoes, pumpkins, plums and things numerous to mention. I soon

Page 48

found many play fellows. My especial chums were Joe and Hector, sons of the plantation driver. The boys were somewhat older than myself. They were skilled in woodcraft, and taught me bow to make bird traps and soon had me out hunting. One morning early, we started out, taking their dog, Spot along. When we reached the woods the dog ran ahead briskly, barking as he went. Shortly he began to bark furiously. "Spot, tree," said Joe, and we hastened on. When we got to the dog he was standing by a tall stump, still barking. "Got er rabbit," said Hector.

"Where?" I inquired.

"En de holler," he replied, and thrusting his arm into it he drew out the poor trembling creature by his hind legs.

"Set him down!" I cried.

"Oh no," said he, "Ee might git 'way."

This was just what I wanted, for I pitied the little animal, but the boys were hunters. They were not going to risk losing their game, so they killed the frightened thing without further ceremony, and put him in their bag. We got three rabbits that morning. I did not enjoy the sport, nor did I partake of the rabbit stew they had for dinner.

Page 49

I did enjoy the night hunts however, for coon and possum were our quarry. I went with some of the young men. While the harmless little rabbit will not even defend himself when attacked, the possum is shy and crafty and the coon will fight. One night the dogs tree'd a coon. Now the wily animal usually selects a tree from which he can reach another, but this coon did not have time to "pick and choose." There was no other tree within jumping distance, so he went out on a limb as far away from the body of the tree as possible. And there he sat. As it was a large tree, it was decided that instead of cutting it down, someone should go up and shake the game off of it. Sandy, one of the party, readily volunteered to do so. Reaching the limb on which the coon was "roosting," he went on it so as to give it a vigorous shaking. The limb broke and down came both man and coon. The coon was dispatched while some of the men went to the assistance of Sandy. We thought he was seriously injured. He was stunned for a moment, but as they raised him up he asked, "Did we git um, boys?" The fall of more than twenty feet was broken by the branches beneath him, and thus he soon was all right again.

These hunts were great, but they were nothing compared to the feasts that followed. These were

Page 50

never held on the same night as the hunt, but on the one following. I never took kindly to either the coon or the possum. The former is usually too fat, and the habits of the other do not appeal to me. But the stories told at these feasts! They would make the fortune of a writer if he could reproduce them. They simply cannot be reproduced, that is all. To get the real, genuine, simon pure article one must be on the ground. And perhaps you think that you have heard good, sound, hearty unadulterated laughter. Well, may be.

You may disfranchise the Negro, you may oppress him, you may deport him, but unless you destroy the disposition to laugh in his nature you can do him no permanent injury. All unconscious to himself, perhaps. It is not solely the meaningless expression of "vacant mind," nor is it simply a ray--It is the beaming light of hope--of faith. God has blessed him thus. He sees light where others see only the blackness of night[.]

Page 51

CHAPTER IV

THE LOVER

"The tide of true love never did run smooth."

PINE TOP, Mr. Ward's country seat, was a beautiful plantation about eighteen or twenty miles from Charleston. The house, an old colonial mansion, stood on elevated ground, well back from the main road, and commanded a fine view of the surrounding country. From the main road the house was reached through a wide avenue, lined on either side by giant live oaks, while immediately in front of the house was a large lawn circled by a wide driveway.

From the front door of the house the barns, stables, gin-house, corn mill and Negro quarters, presented the appearance of a thriving little village. The quarters were regularly laid out in streets, and the cabins were all whitewashed. I once read in a newspaper, a letter from a Northern

Page 52

man who visited the South immediately after the war. He took a rather unfavorable view of the prospects of the Negro, for he said, "There was a lamentable absence of flowers about their cabins." I suppose this "Oscar Wilde" thought the conditions under which the people lived were well calculated to foster love of the beautiful. The poor fellow could not have visited Pine Top however, and many other places I could name, or he would have been delighted to see the well-kept little flower beds near many of the cabins. And no doubt, he would have said they were just "too, too" for words. He might even have been tempted to enter some of those cabins by their neat and tidy appearances which could be seen through the open doors.

Mr. Ward was what was called a "good master." His people were well-fed, well-housed and not over-worked. There were certain inflexible rules however, governing his plantation of which he allowed not the slightest infraction, for he had his place for the Negro. Of course the Negro could not stand erect in it, but, the Negro had no right to stand

Page 53

erect. His place for the Negro was in subjection and servitude to the white man. That is, to Mr. Ward and his class, for while he maintained that the supremacy of all white men over the Negro was indisputable, and must be recognized, still there was a class of white men that he would have prevented from ever becoming slaveholders.

While I repudiate Mr. Ward's views I am bound to believe that there is something in blood. In those parts of the South where aristocratic influence is dominant, opposition to the advancement and progress of the Negro is less than where the contrary is true. Eliminating the Negro altogether, in some of the southern states the "bottom rail" has gotten on top with a vengeance, and where such is the case, it is very bad for the "enclosure."

One evening Mr. Ward sat in his library before a blazing wood fire. He was the picture of contentment; and why should he be otherwise? He had a beautiful wife, two fine boys, hundreds of acres of land and numerous slaves to work them. Furthermore, he had just dined on wild duck. Now I would not tax the credulity of the reader by an exact

Page 54

statement as to how long those ducks had been allowed to hang up after being shot before they were considered "ripe," but, they had reached a stage that would hardly have been appreciated by a man of less "refined" taste than his, for Mr. Ward was a lover of "high game." The aroma that arose from those "birds" during their preparation for the table would not have tempted the appetite of an ordinary man, even if he were very hungry.

Mrs. Ward had joined her husband for a little chat when Jake, the waiting boy, entered.--(Jake was the assistant and understudy of Uncle Sempie, the veteran butler. Uncle Sempie always retired after dinner, leaving Jake to attend to the later wants of his master). "Mingo, fum Mr. Hudson place wan ter see yo, sah," he said.

"All right, let him in," said Mr. Ward.

Presently Jake returned ushering in a very young Negro who appeared to be laboring under some embarrassment. As he entered he said, "Ebenin sah, ebenin ma'am."

"Good evening," replied the lady and gentleman.

Page 55

"Are you Mingo from Mr. Hudson?" asked Mr. Ward.

"Yees, sah."

"How are your master and mistress?"

"Dey berry well, sah."

"Well, Mingo, what can I do for you?"

The young fellow hesitated as if be did not know exactly how to proceed. Both the lady and gentleman looked at him attentively. He was becomingly attired, had a pleasant face, and was evidently a favored servant. At last he mustered enough courage to say, "I come sah ter ax yo p'mission ter cum see Dolly. Dolly is the darter ob Uncle Josh and Ant Peggy, sah," he added.

Mr. and Mrs. Ward strove hard to suppress their mirth as they saw the poor fellow was about to collapse. "Oh," said the lady smiling, "So you would a-courting go, eh?"

"Yees, ma'am," recovering himself a little.

Mr. Ward cleared his throat. "Well Mingo," he asked, "Have you got your master's consent?"

"Oh yees sah."

Page 56

"And you and Dolly understand each other?"

"Yees, sah."

"Are Josh and Peggy willing to have you for a son-in-law?"

"Oh yees, sah, I don ax dem."

"I suppose you behave yourself. I am very particular concerning this matter."

"I know dat, sah. Mas Jeem kin tell yo bout me, sah."

"Well, I guess it is all right. Of course I shall inquire about you. Have you got your ticket?"

Here Mingo produced the desired article. Mr. Ward read it, his brows contracting a little. "This is all right," he said, returning the paper, "Except that it does not way where you are to go. Now I never allow anyone on my place with such a ticket. The next time you visit Dolly you must have a different "ticket." Ask your master to give you one stating plainly that you are to visit my plantation. Do you understand?"

"Yes, sah."

"Well, Mingo, I wish you good luck!" said Mrs. Ward.

Page 57

"Tankee ma'am, tankee sah," and he bowed himself off.

The "ticket" referred to was simply a permit showing that the slave had his or her master's consent to be absent from home. In some instances their destination was mentioned; in others it merely stated that "A-- has my permission to be absent on such a date, or between given dates." Mr. Ward never refused his people "leave of absence," but in every case their destination was clearly set forth. It would not be safe for them to be found "off the coast."

Now I would not insinuate that Mingo was a fickle lover. It is just possible that he wished to visit some of the other girls in the neighborhood simply for the purpose of convincing himself by actual comparison of the superior charms of his own Dolly. His was a monthly "ticket," and under these circumstances we must excuse him for not wishing to have it changed. In fact he determined not to do so. He did not even acquaint Dolly with Mr. Ward's instruction. Possibly he feared that she might have

Page 58

agreed with that gentlemen--from different motives of course.

It was the custom of the owner of "Pine Top" during his

stay on the plantation to visit the "Quarters," ostensibly to

see how his people were getting on, and incidentally, to

note that things were as they should be on the place.

Mingo was aware of this so he thought that on his future

visits to his sweetheart all he had to do was "to lay low"

until Mr. Ward had made his rounds. In this he was

successful for a time but--

"The best laid plans of mice and men, gang aft

agley."

Besides, young love is ever impatient.

One night he took his stand in his usual place of concealment. It had been raining and the weather was decidedly cold. He had waited long after the usual time for the gentleman's visits. "Spec de old feller ain't comin out tonight," he said to himself.

Mingo did not know Mr. Ward. The people on Pine Top expected their master at any hour, and were not surprised to have him present himself at their doors when he thought they were not looking

Page 59

for him. He would sometimes even partake of roast possum or coon. Unaware of these habits Mingo hastened to meet the warm welcome that awaited him at Dolly's cabin. He was destined to receive a warmer welcome than the one he anticipated.

Uncle Josh and Aunt Peggy sat by the fire. Perhaps they were asleep. Dolly and Mingo were sitting at a small table as far away from the old folks as they possibly could get. "I bin ober to Cedar Hill las nite," he began, "An I see'd the new gal dey got. I tink she is----."

"I see'd her," interrupted Dolly, "An I tink she's just horred."

And Mingo deeming discretion the better part of valor said, "I tink so too."

Just then there was a loud rap on the door and Mr. Ward entered! Sometimes the very means we use to conceal our fears serve but to make them plain. The moment Mingo sighted Mr. Ward he became alarmed, but he must appear collected.

"Ebenin sah. Cole nite, sah. How is Missus and de chillun?"

Immediately Mr. Ward knew "the lay of the

Page 60

land." "Oh they are all well. How are all at Laurel Grove?" he asked smoothly.

"Berry well, sah, all berry well."

Mr. Ward turned to speak to the old people, taking good care to place himself between Mingo and the door. When he started to leave the house he seemed to remember something. "Oh, by the way Mingo, did you have your ticket changed?"

"Mas Jeems, he bin gon ter town, sah, an Miss Liza say wait til he cum back."

"Ah, then you had it changed when he came back, did you?" Mr. Ward spoke very deliberately.

"When he git back I so busy I forgot, but I hab um fix sho fore I cum er gen, sah."

It was a cool night, but there were signs of perspiration on Mingo's face as he spoke. "I am afraid to trust your memory, Mingo," he said. Then he stepped to the door placing the silver mounted cow's horn which he always carried about the plantation, to his lips, blowing a loud blast.

Page 61

THE DRIVER

Uncle Joe, as he was called by the Negroes, and, Daddy Joe as he was called by the white folks, was Mr. Ward's driver. He was a plantation Negro, the son of a plantation Negro, but he would not have answered to any of the descriptions usually given to the "plantation Negro." He did not have a receding forehead, a protruding jaw, nor bandy legs. In fact, he bore a striking resemblance to a well formed man. He had a thoughtful expression, and although he was rarely seen to smile, he had a pleasant countenance. He was not harsh with those over whom he had been placed. "Boy, doan lemme put me han on yo," was sufficient to bring the most refractory into line, and this was nor a mere figure of speech, for when his hand did drop on the shoulder of some erring culprit it came down with a force; the effects of which was felt for a long time after, for he was a man of unusual strength.

But Uncle Joe could laugh, and when he was Engaged in relating some particularly ludicrous Adventure of Brer Rabbit and Brer Wolf, to his two boys Joe and Hector, at night when the day's work was

Page 62

done, his sonorous voice could be heard throughout the Quarters.

This night the old man had removed the tension from the boys' minds by completing a Jack O' Lantern story begun on the night before. The story was as follows:

"Wonce der was er man. He lib on won plantation en his wife an chillun dey lib on er noder, seben mile off. Von nite de man tink he go see dem, so he ketch a fat 'possum. He put de possum en some oder tings een er bag en start. Wen he git good way on de road he see er brite light. (Dem Jack O' Lantern always lookin out fur trabblers). De lite blin de man an he los de road. Fus ting he kno he fine heself een a swamp. Den de Jack O' Lantern laf en say, "Now I hab dar bag." De lite gon out quick en de man cudent see he han befo he face."

Here the old man pleaded weariness and sent the boys to bed, promising to finish the story the next night, for though Uncle Joe had never written a continued story he understood the art of creating a demand for the next number. All the following day the boys talked about the probable fate of the luckless

Page 63

traveler. "I bet," said Joe, "Dat Jack Lantin tak de man bag, den kill um."

"He doan hab to kill um he self. All he hab ter do es to tak way he bag en lebe um een de dak, en sum ob dem bad wile varmint wat be een de swomp eat um up," answered Hector.

But to their great relief their father had skillfully extricated the poor fellow from his perilous position, bag and all, with no greater misfortune than the loss of his hat which was brushed off by the low hanging branches. His shoes came off in the soft mud of the place. These he did not stop to hunt for as he was glad to get out alive. The boys, thus satisfied went willingly to bed, while Uncle Joe settled himself for a quick no by the fire. Aunt Binah, his wife, busied herself cleaning up supper dishes. As she went about her work she hummed an old Plantation hymn; the humming grew louder as she Continued, and soon she began to sing--"I run From Pharo, lem me go."

This seemed to arouse her husband, for he Commenced to beat time with his foot. When she

Page 64

reached the chorus he joined in and their strong voices blended harmoniously.

"De hebben bells er ringin, I kno de road

De hebben bells er ringin, I kno de road

De hebben bells er ringin, I kno de road,

King Jesus sittin by de watah side."

"Hush," said Aunt Binah, "Tink I yer de hon." They both listened attentively. Yes, there was another blast. "Wonder wha dat debble wan wid me now," said Uncle Joe. He slipped on his shoes, got his hat and coat, (meanwhile his wife had lighted his lantern), and hurried out. As he stepped outside a third blast assailed his ears; this to direct him, as Mr. Ward had seen the light.

"Um soun like he ober to Josh house. Wonder wha da him now?" he said to himself, hastening along.

"Ah Joe," said Mr. Ward as the driver reached Josh's cabin, "Mingo has forgotten my orders. Take him over to the barn and give him twenty lashes."

"Cum on boy," said Uncle Joe, not unkindly, yet in a tone that indicated there was to be no hanging

Page 65

back. Under these circumstances Mingo must be

excused for not having lingered to say "Good

night." In fact, "his heart was too full for

utterance." And so the line of march was taken up

in silence, Uncle Joe leading with his lantern, Mingo

next, Mr. Ward bringing up the rear. When the

humiliating performance was over, the party broke

up. Mr. Ward returned to the house whistling

softly:--

"From Greenland's icy mountains."

Uncle Joe, wending his way back to his cabin, sang

in a low voice, "There's rest for the weary."

Poor Mingo neither sang nor whistled. As he painfully took the shortest cut for the main road he consoled himself with the thought that--"Faint heart never won fair lady." He did not put it just in that way. What he really did say to himself was "Well, sum time Man hab ter go tru heap to git wife."

Did he win his Dolly finally? We shall see.

Page 66

CHAPTER V

THE HUNTING SEASON AT PINE TOP

"The Old Flag never touched the ground."

The Color Sergeant At Ballery Wagener

GAY hunting parties composed of friends from the city and ladies and gentlemen from the surrounding plantations often assembled at Pine Top. Many amusing tales were told there of the "Stag Fright" and blunders of amateur sportsmen on their first deer hunt. There was a Mr. Brabham, a carpenter, who being placed at a "stand" for the first time, and told not to let the deer pass him, waited in breathless anxiety. Soon a magnificent buck came bounding towards him almost within arms' reach. Throwing

Page 67

up his arms wildly, his gun held aloft, he exclaimed, "I wish I had my hatchet!" while the terrified animal sped on to be brought down by a more collected hunter on the next stand.

This year however, the festivities were cut short for Mr. Ward was often called to the city as indeed were many of the other gentlemen who were accustomed to join the gay throng at Pine Top. It was soon known that they were attending Mass Meetings and Conventions. Sometimes Mr. Ward would be absent several days. There were strange whisperings among the Negroes. "Dat ting comin," they said mysteriously to each other, "Pray my brudder, pray my sister." I listened with wonderment, but was taught to say nothing.

Uncle August was Mrs. Ward's right hand man. He was equally at home in the fields or in the house, and could always be depended on in an emergency. He was full of humor, a born mimic, and could set those about him in gales of laughter, without seeming to try. Mrs. Ward frequently conversed with him when he was engaged in some task under her directions about the house, or grounds. One day while he was moving some pieces of furniture from

Page 68

one room to another the lady said, "Daddy August, do you know there is going to be war?"

"War! ma'am, Wey, ma'am," Anyone who saw and heard the old man would have been ready to affirm most positively that this was the very first intimation he had had of the impending conflict.

His mistress certainly thought so.

"Why here," she replied.

"On dis plantation, ma'am?"

"Oh no, I don't mean that exactly, but you see, the Yankees are determined to take our Negroes from us, and we are equally determined that they shall never, never do so. Why Daddy August, don't we treat you all well?"

"Ob cose yo does, ma'am. Wha dey bodder deyself bout we fer?"

"That's just it; they are simply jealous to see us getting along so well, and they want to take our Negroes and put them at all kinds of hard work, like horses and mules. They are sending emissaries among our Negroes, to make them dissatisfied.

"Wha dem is, Miss Em'ly?" (Of course he had not the slightest idea what an emissary was!)

"Oh they are men who will try to sneak around

Page 69

and talk to the Negroes."

"Wha dey gwine say?"

"Well, they will tell the Negroes that they are their best friends, and so on, just for the purpose of deceiving them you know."

For a second there was a twinkle in Uncle August's eyes which Mrs. Ward did not observe. "Mis Em'ly," he asked with a startled expression on his face, "Wha dem embissary look lak."

"Oh they will be in disguise, you know, but they try to look like our own people. Why?"

"Well yo kno, toder day wen I bin gon over ter Mr. Hudsin, ma'am? When I coming back an git mos to de big gate, I see er strange man comin' up de road. Time as I see un I tink dem "Kidnabber" cause you kno dey car off Mr. Hudsin Tom."

"Now Daddy August," interrupted Mrs. Ward, "I don't believe any kidnapper carried off that boy. I think he just ran away."

"Wha he hab ter run away fer, Mis Em'ly? I sho Mr. Hudsin es er good man!"

The aforementioned Tom was at this very moment on the way to freedom by means of the "Underground

Page 70

Railroad," and this Uncle August knew very well.

Enyhow I fraid dem kidnapper so I mak hase git inside de gate. Wen he git ter de gate he call ter me "Cum yer. I wanter tell yo somting."

I say, "Cum een, sah."

He say, "No, yo cum yer."

I say, "I see Mas Henry cummin an I ain't ga time. (You kno Mas' Henry gon ter town dat day). Time as I say dat he hurry way."

"I see yo ergan," he say. Den I say ter maself I know dat da "kidnabber."

"Did you see him again?" asked Mrs. Ward quietly but she did not succeed in hiding her alarm from the old man. He knew what effect his story (and it was a great big one), would have.

"No, ma'am!" he answered, "An I doan wanter see um gan noder."

Mrs. Ward determined to acquaint her husband with what she had heard, as soon as possible. Therefore, when Mr. Ward returned from the city that evening, she informed him privately of what August had told her. He was even more disturbed than she

Page 71

was. "And," she added, "Daddy August is frightened half to death."

They both concluded that the stranger was a Yankee spy. "It will not be good for him if I find him prowling about here," said Mr. Ward, "I shall question August further about it."

He found an opportunity that evening, without appearing to attach any importance to the incident, to question the old man closely. However, August had nothing to add to what he had told Mrs. Ward. He considered it was already a sufficient "whopper."

But Mr. Ward was uneasy. He told Uncle Joe to have two horses saddled, and they rode over to Mr. Hudson's. He did not acquaint the driver of the object of the visit, but that was not necessary as August and Joe had already had a hearty laugh over the hoax. From Mr. Hudson's they went to Mr. Benton's. To each of these gentlemen Mr. Ward related what he had heard. Neither of them had seen or heard of any stranger in the neighborhood. They both promised to look out, and if such was found it would not be their fault if he did not

Page 72

give good account of himself. But the mysterious man was never found of course.

Some days after the incident just related Mrs. Ward was superintending some work which Uncle August was doing in the garden; setting out plants And the like, for it was now early spring. A team Drove up to the house and the men proceeded to Unload a tall pole. "Wha dey gwine do out dey, Mis Em'ly?" asked the old man innocently.

"Why they are going to set up a flagpole. You see we are to have a government of our own so we must have a flag of our own; the Confederate flag. It is going to be a very pretty one, too."

"No priteer dan de old flags upstars."

"Oh yes, a great deal prettier," but the lady was thinking of the old flag her father and grandfather had fought under."

The old man glanced at her. "Well," he said, "It hab ter be berry puty ter beat de old flag." There was more in his words than he meant his mistress to understand.

"Daddy August," said Mrs. Ward, as though not

Page 73

wishing to speak any more about flags, "We will put that right here," (alluding to a plant the old man held in his hands).

August did as directed, but he was not quite through yet. Presently he said, "Mis Em'ly, wha yo gwine do wid de old flag? Yo pa an yo granpa use ter tink er heap ob dat one."

"Burn it up!" replied Mrs. Ward in rather a vehement tone.

Uncle August knew he had said enough.

It was now about the middle of April 1861. Important matters seemed to require Mr. Ward's attention in the city, and much of his time was spent there. One evening Mrs. Ward told Uncle Ben he must meet Mr. Ward at the station the following day with a pair of horses. He usually used a single horse and a dog cart for this purpose. "Sumting up," said the old coachman to himself.

Mr. Ward had not been home for near two weeks. The Negroes on the plantation knew war was approaching, for though they could not read the newspapers, it is remarkable how well posted they were

Page 74

in regard to the trend of events. They knew also that their master's long absence was to be accounted for in the coming conflict. His return therefore, was anxiously awaited by them; as they hoped to gain some information as to how matters actually stood.

The next morning Uncle Ben had his team in tip top shape, and rigged up with his regulation coachman's outfit, including his shiny silk hat. He carried Jake along to open the gates. "I kno wha he want," he had said, "But wait little bit." And he drove away.

As they left the station Mr. Ward said, "Save your horses Ben," but when they swung into the plantation avenue he told the coachman to "let them go."

Uncle Ben pulled up his lines, drew the whip lightly across his horses and said, "Git out."

Tom and Jerry responded and they came up the "home stretch" in fine style. The whole family stood on the front porch waving their handkerchiefs. Mr. Ward waved his in return. As Uncle

Page 75

Ben drew up at the stepping stone, Mr. Ward sprang out, ran up the steps, embraced his wife and children, and kissed his mother-in-law, (a thing which I believe men seldom do). "We have taken the fort," he said, as they entered the house.

Page 76

CHAPTER VI

THE BEGINNING OF THE END

THAT night conflicting emotions governed those who lived on "Pine Top" plantation. In the big house there was gladness and rejoicing, while at the Quarters there was groaning and lamentation. The Negro believed that as long as Major Anderson held Fort Sumter their prospects were at least hopeful; but when Sumter fell, they felt that their hopes were all in vain. Though the future looked dark, there were two on the place who never gave up; Uncle Ben and Aunt Lucy. You are acquainted

Page 77

with the old man already. Aunt Lucy was the plantation nurse. Years of hard and faithful toil in the fields had gained for her respite from active labor. It was her sole duty now to take care of the young children of the women who had to go into the rice and cotton fields, and those mothers were glad indeed to have such a kind christian woman as she was to look after their little ones while they were at work. The old woman, though well on in years, was still hale and hearty. "Min, wha I tell yo. De Master gwine bring we out," were her words of encouragement to those who were ready to despair. Uncle Ben's words were, "Dem buckra kin laf now, but, wait tel bime by.'

Between the "big house" and the Quarters there was a spring from which the people got their drinking water. Every afternoon a long line of children might have been seen with "piggins" on their heads, taking in the supply for the night. On the evening of Mr. Ward's return, the children did not appear. In their stead, and at a later hour, their parents came. It was noticeable too, that they lingered at the spring, being concealed from view by the trees that grew about it. The reason of all this was that

Page 78

arrangement had been made with Jake that as soon as possible after dinner, he was to run down and tell them any news he might gather during that meal. Jake, as a possible gatherer of news! Why that was absurd! He was spry enough about the house and dining-room, but otherwise he was as dense as a block of stone. At least, that was what his master would have said of him. This density on the part of the Negro was, in fact, a weapon of defense--the only one he had. Do you think Captain Small could have run the Planter out of Charleston harbor if it was thought he had sense enough to do so? No, indeed! He never would have had the chance.

I said Jake was to run down. That was a mistake. He was much too wise for that. After dinner was over he sauntered down the back steps as soon as he could. Upon reaching the ground, he thrust his hands into his pockets, and walked slowly toward the spring, whistling, "Way Down Upon the Swanee River," as though he didn't have an idea in his head. "He comin' now," said Aunt Lucy, "Well mi son, wha he say," as the boy drew near.

"Well, ma'am, dy tak de fote. We done now" was heard on all sides.

Page 79

"Wait, chilun, hope pray," was the old woman's encouraging words as she proceeded to question the boy further. "Wha dey do wid Majer Ande'son?"

"Dey le him go."

"Wha dey say bout him?"

"O he say do Majer es er brave man. He mak er speech befo he cum out. He say, (and Jake drew himself up to imitate the Major) "Genlemen, if I had food fer my men, an ambunachun I be dam if I wed le yo cum on dose gates!"

"Amen, bress de Lawd!" cried the old woman.

"O Ant Lucy!" said Manda, the housemaid, abashed at the old woman's endorsement of the somewhat impious remarks of the gallant Major.

"Hole yo tong yo braze piece. Go on Jake mi son."

But the boy had little more to tell and so the people went sadly back to their cabins. Aunt Lucy's parting words were, "Hope chilun, pray chilun."

The next day Mr. Ward gave Uncle Sempie orders to prepare for a large dinner party that would be given by him in a few days. This was to be another addition to the long list of similar functions that had taken place at Pine Top under the supervision

Page 80

of the old butler. Among them there was one to which the old man often referred with special pride. It was the great dinner given by Mrs. Ward's grandfather, (for Pine Top had been the home of the Bale's for generations), in honor of the Hon. John C. Calhoun.

When the day for Mr. Ward's great dinner came, the guests began to arrive early; some on horseback, others in carriages, the coachmen vying with each other in the style in which they came up the avenue, and pulled up at the stepping stone. There were distinguished ladies and gentlemen. There were horses that had records, and some of the coachmen had records, too. York, Mr. Boyleston's coachman was one of these. His horses always showed the best of care and his stables were models of neatness and appointment. He had three well grown stable boys under him who were kept at rubbing and polishing constantly. The boys slept at the stable while York occupied a neat little cabin on a hill a short distance away. Seen early in the mornings coming down to look after his stock, with a cigar in his mouth, he might easily have been taken for Mr.

Page 81

Boyleston himself. As he neared the stable he would say, "Ahem!" and each boy popped his head out and would say, "Sah." Upon entering he went through a minute inspection, and it was for their best interest if everything was found in perfect order. York had the record of having once knocked his master down.

The circumstances which led to this daring performance were these: Mr. Boyleston took great pride in his horses. His stock was always of the finest strain, and it may be added that he appreciated his coachman's ability as a whip and manager. His special pride was a span of dark gray trotters of undoubted pedigree. For these he had bought an expensive pair of blankets. "Now, York," he had said, "These blankets have cost me a great deal of money. Be very careful with them. Never allow the horses to wear them at night."

York took as much pride in those beautiful coverings for his horses as did his master. He never permitted the boys to touch them, but each morning after the finishing touches to the animals, he adjusted them with his own hands. One morning he

Page 82

led the horses out on to the floor of the barn, hitched them, and threw the blankets lightly over them, while he took another horse outside to water. Unfortunately he had tied the animals too closely together. They began biting at each other as horses are wont to do. One of them got his teeth into the blanket of the other, pulled it down on the floor, and together they trampled it under hoofs. The boys were at work at a distant part of the place therefore could not see what was going on. When York returned he was dismayed at the sight. The once beautiful blanket now stained and torn, lay under the feet of the horses! He picked it up, but there was nothing he could do to repair the damage. He placed it on the horse as best be could. To add to his confusion be saw Mr. Boyleston coming down to the stables for his usual morning inspection. The coachman walked to the further end of the barn, pretending to be engaged at some work, while his heart beat almost loud enough to be heard.

"York," called out Mr. Boyleston as soon as he entered and his eyes fell on the damaged blanket, "Did I not tell you never to let the horses wear

Page 83

their blankets at night?"

"I dident, sah, de----."

"You are a----liar, sir----."

Out flew York's right arm before he knew it, and down went his master. He walked out into the lot, folded his arms, and stood facing the door. Mr. Boyleston got up. As he came to the door York said, "Shoot me down, sah." His master drew his revolver. "Fire, sah, I'se ready," and York stood unflinchingly.

Mr. Boyleston put up his pistol. "Come here to me, York," he said.

"No, sah."

"May I come to you?"

"Yees, sah! I wudent ham a hair on yo head."

"York," said Mr. Boyleston walking out to his coachman, "How came that blanket to be in such a condition?"

York gave his master a straight account of the whole occurrence. "Here is my hand; I was wrong," was Mr. Boyleston's magnanimous answer, "Do not mention this to anyone."

Page 84

There were not many masters like this one.

Mr. Ward's dinner was a grand affair, and no one rejoiced at its success more than old Uncle Sempie. After dinner the party went out on the lawn where a stand had been erected. Amid cheers the new flag was raised and many gentlemen made speeches which all seemed to be aimed at the "White House." I did not know where that was, but Uncle Ben said it was where "dem buckra wud nebah git." Later I learned that the White House was at Washington, and sure enough they never got there.

Mr. Ward now deemed it necessary to have the plantation carefully guarded at night. For this purpose he chose two young Negroes, brothers, Titus and Pompey. The confidence the southern white had in the Negro, and the fidelity of the latter to the trust reposed in them speak volumes. Here was this master perfectly satisfied to place the safety of himself and family in the hands of these men, on whom, at that moment, he was seeking to rivet the chains of slavery forever. The men were to relieve each other, and at stated intervals, if things were all right, they were to come under Mr. Ward's window

Page 85

and sing out, "All is well!" If things were otherwise, they were to pull a knob which would ring a bell in their master's room.

Titus was noted for his prodigious strength, and an equally enormous appetite. He created great amusement one night during his watch by standing under the window and shouting, "All is well and I'se hungry!" Mr. Ward took the hint and thereafter the men were each provided with a large "hoe cake," lined with fat bacon every night before going on duty.

The time drew near for our return to the city. We must not remain on the plantation after the tenth of May, for those not acclimated are liable to contract malarial fever. Soon we bid farewell to the old place and to the many kind friends we had met there. The kind-hearted people loaded us with simple gifts. My stay in the country had been most pleasant.

Page 86

CHAPTER VII

IN TOWN AGAIN

"Mischief, thou art afoot."

ON arriving in Charleston we found great excitement there. Men were going about the streets wearing blue cockades on the lapels of their coats. These were the "minute men," and the refrain was frequently heard,

"Blue cockade and rusty gun

We'll make those Yankees run like fun."

Soldiers on parade often passed by our house,

Page 87

and we ran to see them. One day a troop of horses went by. The ladies waved their handkerchiefs and the officers saluted. I heard they were on their way to the "Front." I wanted very much to know where that was, therefore, when Uncle Ben and I went to the stable I asked, "Uncle Ben, where's the 'Front?' "

The old man made me no immediate reply. In fact, he never did. Knowing he heard me I waited patiently. Presently he looked up:--"De front, boy, es de place weh dem young buckra gwine ketch de debble," he said, and resumed his work.