A Tribute for the Negro:

Being a Vindication of the Moral,

Intellectual, and Religious

Capabilities

of the Coloured Portion of Mankind;

with Particular Reference to the African Race:

Electronic Edition.

Armistead, Wilson, 1819?-1868

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Kevin O'Kelly and Chris Hill

Images scanned by

Chris Hill

Text encoded by

Bethany Ronnberg and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 1.5MB

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999

Call number 326 A728t (Wilson Annex, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

The publisher's

advertisements following p. 564 have been scanned as images.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and

Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

LC Subject Headings:

- LC Subject Headings:

- Black race.

- Slavery -- History.

- Blacks -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Biography.

- 2000-06-06,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-08-31,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-08-26,

Bethany Ronnberg

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-07-19

Chris Hill and Kevin O'Kelly

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

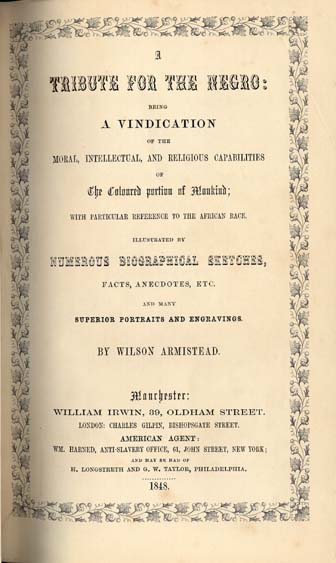

A

TRIBUTE FOR THE NEGRO:

BEING

A VINDICATION

OF THE

MORAL, INTELLECTUAL, AND RELIGIOUS CAPABILITIES

OF

The Coloured portion of Mankind;

WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE

AFRICAN RACE.

ILLUSTRATED BY

NUMEROUS BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES,

FACTS, ANECDOTES, ETC.

AND MANY

SUPERIOR PORTRAITS AND ENGRAVINGS.

BY

WILSON ARMISTEAD.

Manchester:

WILLIAM IRWIN, 39, OLDHAM STREET

LONDON:

CHARLES GILPIN, BISHOPSGATE STREET.

AMERICAN AGENT:

WM. HARNED, ANTI-SLAVERY OFFICE,

61, JOHN STREET, NEW YORK;

AND MAY BE HAD OF

H. LONGSTRETH AND G. W. TAYLOR,

PHILADELPHIA.

1848.

Page verso

MANCHESTER:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM IRWIN,

39, OLDHAM STREET.

Page vi

TO

JAMES W. C. PENNINGTON, FREDERICK DOUGLASS,

ALEXANDER CRUMMELL,

AND

MANY OTHER NOBLE EXAMPLES OF ELEVATED HUMANITY

IN THE NEGRO;

WHOM FULLER BEAUTIFULLY DESIGNATES

"THE IMAGE OF GOD CUT IN EBONY:"

THIS VOLUME,

DEMONSTRATING, FROM FACTS AND TESTIMONIES,

THAT THE

WHITE AND DARK COLOURED RACES OF MAN

ARE ALIKE THE CHILDREN OF ONE HEAVENLY FATHER,

AND

IN ALL RESPECTS EQUALLY ENDOWED BY HIM;

IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED.

Page vii

PREFACE.

In reviewing the history of mankind, we may observe, that very soon after the creation of our first parents in innocence and happiness, sin and misery entered into the world. The evils of life commenced in the earliest ages, and subsequent history and experience testify, that in all their variety of form and character they have continued to exist in every successive generation to the present time.

To combat these evils, by endeavouring to effect their removal or correction, is the most pleasing and useful occupation in which we can engage ourselves. Providence has wisely instituted, in every age and in every country, a counteracting energy to diminish the crimes and miseries of mankind, which the influences of Christianity have increased, by unfolding to it the widest possible domain. "At her command, wherever she has been fully acknowledged, many of the evils of life have already fled. The prisoner of war is no longer led into the amphitheatre to become a gladiator, and to imbrue his hands in the blood of his fellow-captive, for the sport of a thoughtless multitude. The stern priest, cruel through fanaticism and custom, no longer leads his fellow-creature to the altar, to sacrifice him to fictitious gods. The venerable martyr, courageous through faith and the sanctity of his life, is no longer hurried to the flames. The haggard witch, poring over her incantations by moonlight, no longer scatters her superstitious poison amongst her miserable neighbors, nor suffers for her crime."

Page viii

So long as any of the evils of life shall remain, accompanied, as they must inevitably be, with misery and guilt, the Christian will find himself impelled by an impulse of duty to oppose them; and his energies will be roused into active resistance, in proportion to the magnitude of the evil to be overcome.

The most extensive and extraordinary system of crime the world ever witnessed, which has now been in operation for several centuries, and which continues to exist in unabated activity, is NEGRO SLAVERY. This hateful system, involving a most incalculable amount of evil, and entailing a measure of misery on the one hand, and guilt on the other, beyond the powers of language to describe, entitles its victims to the strongest claims on our sympathy.

"If, among the various races of mankind," says the pious Richard Watson, "one is to be found which has been treated with greater harshness by the rest--one whose history is drawn with a deeper pencilling of injury and wretchedness--that race, wherever found, is entitled to the largest share of compassion; especially of those, who, in a period of past darkness and crime, have had so great a share in inflicting this injustice. This, then, is the Negro race--the most unfortunate of the family of man. From age to age the existence of injuries may be traced upon the sunburnt continent; and Africa is still the common plunder of every invader who has hardihood enough to obdurate his heart against humanity, to drag his lengthened lines of enchained captives through the deserts, or to suffocate them in the holds of vessels destined to carry them away into interminable captivity. Africa is annually robbed "of FOUR HUNDRED THOUSAND" of her children. Multiply this number by the ages through which this injury has been protracted, and the amount appals and rends

Page ix

the heart. What an accumulation of misery and wrong! Which of the sands of her deserts has not been steeped in tears, wrung out by the pang of separation from kindred and country? And in what part of the world have not her children been wasted by labours, and degraded by oppressions?"

The hapless victims of this revolting system are men of the same origin as ourselves--of similar form and delineation of feature, though with a darker skin--men endowed with minds equal in dignity, equal in capacity, and equal in duration of existence--men of the same social dispositions and affections, and destined to occupy the same rank in the great family of Man.

The supporters and advocates of Negro Slavery, however, in order to justify their oppressive conduct, profess, either in ignorance or affected philosophy, to doubt the African's claim to humanity, alleging their incapacity, from inherent defects in their mental constitution, to enjoy the blessings of freedom, or to exercise those rights which are equally bestowed by a beneficent Creator upon all his rational creatures.

White men, civilized savages, armed with the power which an improved society gives them, invade a distant country, and destroy or make captive its inhabitants; and then, pointing to their colour, find their justification in denying them to be men. A petty philosophy follows in the train, and confirms the assumption by a specious theory which would exclude the Negro from all title to humanity. Thus would they strike millions out of the family of God, the covenant of grace, and that brotherhood which the Scriptures extend to the whole race of Adam.

The calumniators of the Negro race--those who have robbed them of their lands, and still worse, of themselves--

Page x

delight to descant upon the inferiority of their victims, withholding the fact, that they have been for ages exposed to influences calculated to develope neither the moral nor the intellectual faculties, but to destroy them. It may, perhaps, be fairly questioned, whether any other people could have endured the privations or the sufferings to which they have been subjected, without becoming still more degraded in the scale of humanity; for nothing has been left undone, to cripple their intellects, to darken their minds, to debase their moral nature, and to obliterate all traces of their relationship to mankind; yet, how wonderfully have they sustained the mighty load of oppression under which they have been groaning for centuries!

Prejudice and misinformation have, for a long series of years, been fostered with unremitting assiduity by those interested in upholding the Slave system--a party, whose corrupt influence has enabled them to gain possession of the public ear, and to abuse public credulity to an extent not generally appreciated. In an age so distinguished for benevolence, we call only thus account for the indifference manifested towards this unfortunate race, and from the fact that they are supposed to be in reality destined only for a servile condition, entitled neither to liberty nor the legitimate pursuit of happiness.

Has the Almighty, then, poured the tide of life through the Negro's breast, animated it with a portion of his own Spirit, and at the same time cursed him, that he is to be struck off the list of rational beings, and placed on a level with the brute? Is his flesh marble, and are his sinews iron, or his immortal spirit condemned, that he is doomed to incessant toil, and to be subjugated to a degradation, bodily and mental, such as none of the other of the children of Adam have ever endured? Away for ever with an idea so

Page xi

absurd! The subjugation of a large portion of mankind to the domination and arbitrary will of another, is as unnatural as it is contrary to the principles of justice, and repugnant to the precepts and to the spirit of Christianity; and in the advancing circumstances of the world, nothing can be more certain, than that Slavery must terminate. It is a blot which can never remain amidst the glories of Messiah's reign.

My present purpose is not to enter into a recital of the horrors of the Slave system in any of its revolting details. The secrets of the dreadful traffic are veiled in those coffin-like spaces in the interior of Slave ships, in which the wretched victims are packed as logs of wood, their limbs loaded with manacles and chains, to be succeeded by the scourgings of the cruel driver! But I will forbear; the mind shudders at the idea of a serious discussion of deeds so hateful, which no prospect of private gain, no consideration of public advantage, no plea of expediency, can ever justify.

The purport of the present volume, in contradistinction to the idea of the Negro being designed only for a servile condition, is to demonstrate that the Sable inhabitants of Africa are capable of occupying a position in society very superior to that which has been generally assigned to them, and which they now mostly occupy;--that they are possessed of intelligent and reflecting minds, and however barren these may have been rendered by hard usage, and have become indeed as "fountains sealed," that they are still neither unwatered by the rivers of intellect, nor the pure and gentle streams of natural affection. By a relation of facts, principally of a biographical nature, many of them now published for the first time, I hope to counteract that deeply-rooted prejudice, the growth of centuries, which

Page xii

attaches itself to this despised race--facts which render a practical negative to the imputation of inevitable inferiority; demonstrating, on the other hand, that, when participating in equal advantages, they are not inferior in natural capacity, or deficient of those intellectual and amiable qualities which adorn and dignify human nature.

How far the attempt is successful must be left to the reader's decision, Whether it result in convincing the sceptical, or in confirming those already persuaded of the truth of the position maintained, may it engender a more lively feeling of brotherly sympathy towards this afflicted people, by demonstrating them to be capable of every generous and noble feeling, as well as of the higher attainments of the human understanding. Once convinced of this, we cannot contemplate with indifference their bodily and mental sufferings, but rather desire that every barrier may be removed which impedes their attaining to that station in society which an all-wise and beneficent Creator designed for them.

Should the facts recorded be deemed of too insulated a nature to elucidate any general theory (most countries having produced some individuals of unusual powers, both of body and of mind), I may observe, that they are only a fractional part of what might have been adduced. I have still in reserve a mass of additional facts, teeming with evidence the most unequivocal, that the Almighty has not left the Negro destitute of those talents and capabilities which he has bestowed upon all his intelligent creatures, which, however modified by circumstances in various cases, leave no section of the human family a right to boast that it inherits, by birth, a superiority which might not, in the course of events, be manifested and claimed with equal justice by those whom they most despise.

Page xiii

I should be wanting in gratitude, were I to omit to acknowledge the kindness of many friends who have aided me during the progress of the work. Amongst these, I may particularly mention Thomas Thompson, of Liverpool; Thomas Scales,* and Thomas Harvey, of Leeds; Jacob Post, of London; Edward Bickersteth,* Rector of Watton; Joseph Sturge, of Birmingham; James Backhouse, of York; Thomas Winterbottom, M.D., North Shields; Captain Wauchope, of the Royal Navy; with many others. To Robert Hurnard, of Colchester, I am indebted for a Narrative and several M.S. letters of Solomon Bayley, of which I regret being able to avail myself only to a limited extent. Nor should I omit a tribute of thanks to my friend Bernard Barton, for his appropriate Introductory Poem, which adds to the interest of the volume.

I may also acknowledge having frequently availed myself of the researches of Dr. Lawrence, and the more recent ones of Dr. J. C. Prichard, whose work on the History of Man is the ablest extant in any language.

I have also derived much information from the work of

the Abbé Grégoire, entitled "De

la Littérature des

*

The reader will observe, throughout the present volume, except in the

first plate, engraved under other auspices, an omission of the title of

"Reverend," usually applied to Ministers of the Gospel. It is far from

my wish to appear uncourteous; but whilst esteeming the virtuous and

the good of every class, I feel a decided objection to the use of this title,

on the ground of its being one assigned to the Almighty himself, whose

name is Holy and Reverend. (Psalm cxi. 9.) It is to be regretted that

Christian ministers, servants of Him who "made himself of no reputation,"

should feel satisfied with this appellation being used, both in public and

private addresses, from their fellow-mortals. Neither the prophets of old,

nor the apostles, nor any of the immediate followers of Christ, however

eminent, required such an adulatory title, the tendency of which is, to

exalt the fallen creature rather than to honour the Divine Creator.

Page xiv

Nègres, ou Recherches sur leur Facultés Intellectuelles, leur Qualités Morales, et leur Littérature," &c. I am indebted to Thomas Thompson, of Liverpool, for this scarce volume, who kindly presented me with a copy of it, which is rendered additionally valuable from its being one presented by the Abbé in his own hand-writing to the late William Phillips, of London. To Gerrit Smith of Peterboro', U. S., I am also indebted for an English translation of the same, by D. B. Warden, Secretary of the American Legation at Paris. This admirable work includes a mass of information, the accuracy of which may be thoroughly relied upon, being the production of a man of great erudition and rare virtues, well known in the learned societies of his day. He was formerly Bishop of Blois, a member of the Conservative Senate, of the National Institute, the Royal Society of Gottingen, &c.

It was partially announced that a list of Subscribers would be appended to the present volume, but as this would have occupied nearly thirty pages, it was thought preferable to extend the Biographical portion of the work, which now exceeds by about one hundred pages the number originally intended. The only object in publishing such a list, would have been to afford a demonstration of the feeling and interest existing on behalf of the oppressed race. Suffice it to say, that it embraces nearly a thousand of the most conspicuous characters in the walks of benevolence and philanthropy, both in Great Britain and America, including the Sovereign of the most enlightened country of the world.

The proceeds arising from the sale of the "TRIBUTE for the NEGRO" will be appropriated for the benefit of the Negro race. On this ground, as well as in consideration of the primary design of publication, the friends of

Page xv

humanity will be interested in promoting its circulation. By so doing, they will advance the cause of freedom, by establishing the claims of depressed, degraded, suffering, and almost helpless millions.

It may be observed, that in making the Biographical selection for this work, the author has been governed by no sectarian prejudice. With due regard to the primary object in view, he has embraced, in support of the proposition maintained, all classes, irrespective of their particular religious tenets. The Episcopalian, the Presbyterian, the Quaker, and the Moravian, are all alike included, not even excepting the half-civilized barbarian, on whom the light has but dimly shone. Whatever our own particular views may be, charity compels us to believe that the virtuous and the good are acceptable to the Universal Parent. A good life is the soundest orthodoxy, and the most benevolent man is the best Christian. Diversity of opinion is not a bar to the favour of Heaven, and it ought not to operate to the prejudice of our neighbor. We ought rather to bear and forbear with each other, remembering that the Sacred Mount of Divine Mercy is open alike to every humble traveller--"God is no respecter of persons; but in every nation, he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is accepted with him." 'Tis these that constitute the "countless myriads" that shall be gathered from "all nations, kindreds, and tongues," to ascribe, throughout the boundless ages of eternity, hallelujahs and songs of incessant praise before the throne of the King Supreme.

Having now completed my undertaking, after soliciting the Divine blessing upon it, I bequeath it as a legacy to the injured and oppressed. Though the design of the publication will, I trust, be deemed a sufficient apology for its appearance, I am prepared for a diversity of sentiment

Page xvi

being expressed as to its propriety or necessity. I should count myself unworthy the name of a man or a Christian, if the calumnies of the bad, or even the disapprobation of the well-disposed, had deterred me from the performance of that which a feeling of duty prompted me to undertake. I court no man's applause, neither do I fear any man's frown. Conscious of many imperfections, I feel thankful in having completed this humble "Tribute" in aid of the cause of Freedom, Justice, and Humanity; and it will be a satisfaction to reflect, that a portion of my time has been employed on behalf of the most oppressed portion of our race, at least with a design to promote their welfare.

W. A.

Leeds, 10th Month, 1848

Page xvii

CONTENTS.

- AN INQUIRY INTO THE CLAIMS OF THE NEGRO RACE TO HUMANITY, AND A VINDICATION OF THEIR ORIGINAL EQUALITY WITH THE OTHER PORTIONS OF MANKIND: WITH A FEW OBSERVATIONS ON THE INALIENABLE RIGHTS OF MAN; THE SIN OF SLAVERY, &c., &c.

- CHAPTER I.--PAGE 3.

Sin of Slavery--Delusion respecting the moral and intellectual capacity of the Negro--An important question--To despise a fellow-being on account of any external peculiarity, a sin--Christianity the manifestation of universal love--Inquiry into the causes of the diversity characterising various nations and people--Analogous in animals-- Connection between the physiological, moral, and intellectual characters in Man--The diversities trifling in comparison with those attributes in which they agree--Nothing to warrant us in referring to any particular race an insurmountable deficiency in faculties-- Scripture testimony to unity of origin in the human race. - CHAPTER II.--PAGE 17.

The idea that moral and intellectual inferiority are inseparable from a coloured skin, a fallacious one--Refuted by facts--Apparent inferiority of the Negro accounted for--Extent and pernicious consequences of Slavery and the Slave Trade--Prevent the civilization of the Negro--The same effects observable on any people under similar treatment--Instanced in European Slaves--loose his shackles, and the Negro will soon refute the calumnies raised against him. - CHAPTER III.--PAGE 26.

False Theory of Rousseau and Lord Kaimes--Injurious to the best interests of humanity, and contrary to Scripture--Injuries done to the Negro on the ground of inferiority--Shocking effects resulting from this idea--Civilized nations before the Christian era--Romans, and their ancestors--Our own--Anecdote related by Dr. Philip--

Page xviiiRemarks of Cicero respecting them--Christian guilt towards Aborigines-- Dr. Johnson on European conquest--Slavery justified by representing the Negro a distinct species--And even a brute--Arguments of Long--Strange book published at Charleston--Chambers' reply--Inferiority ascribed to other races--The Esquimaux--The whole refuted by Dr. Lawrence.

- CHAPTER IV.--PAGE 43.

Deduction of an affinity between the Negro and the brute creation, a mere subterfuge--European physiognomy often similar to the Negro's --Blumenbach's Negro craniæ--Imperceptible gradations of one race into another--Further analogies in animals--Effects of the civilizing process in improving the form of the head and features-- Exemplifications--Illustrated in the case of Kaspar Hauser--Testimony of Dr. Philip--Dr. Knox on Negro craniæ--His important conclusion--Dr. Tiedeman's experiments--Conclusive observations of Blumenbach--And others--The civilization of many African nations superior to that of European Aborigines--No deviations in the races of Man sufficient to constitute distinct species--Departures from the general rule accounted for--Equal variations observable in our own country--Remarkably exemplified in Ireland. - CHAPTER V.--PAGE 56.

Complexion the most obvious external distinction in Man--Analogous in animals--Chief cause of diversity of Colour--Peculiarities of Structure and Complexion become hereditary--Illustrations--In the House of Austria--The Gipsies--Jews--Persons of the same blood--Amongst the great and noble--The Colour of Man not always corresponding with Climate explained--Persistency of Colour not so great as supposed--Instances of Negroes becoming light-coloured --Of Whites who have become black--True Whites born among the Black races--If Colour is a mark of inferiority in Man, it attaches a stigma to a great portion of the inhabitants of the world--The Hindoos--Their learning two thousand years ago--Natives of Terra del Fuego much lighter than the Negro, but inferior in the scale of intelligence--Colour of the Negro a merciful provision--Dr. Copland's remarks on this subject--The inquiry into Unity of Species admirably summed up by Buffon. - CHAPTER VI.--PAGE 72.

Not in external Characteristics alone that Man is pre-eminently distinguished--Uniform traits in human nature--Superior Psychical endowments--Reason and intellect--Universal belief in a Supreme

Page xixBeing--And ideas of his attributes, &c.--Prevalence of similar inherent ideas amongst the various Negro tribes--They possess the same internal principles as the rest of mankind--A portion of that Spirit which is implanted in the heart of "every man "--Further coincidence when converted to Christianity--Early attempt to convert the Slaves of the Caribbee Islands--Its singular success; as also in other Islands--Subsequently in Africa and the West Indies --After restoring to the Negro his rightful liberties, it is our duty to promote the cultivation of his moral and religious faculties--Final blending of all the various tribes in harmony.

- CHAPTER VII.--PAGE 81.

Deep-rooted prejudice to eradicate respecting Colour in Man--Less in Europe than in the New World--Evinced in the case of Douglass-- National expression of sympathy for him from the British public-- The "DOUGLASS TESTIMONIAL"--British Christians respect the Divine image alike in ebony and ivory--Effects of prejudice in South Africa--Americans deeply implicated in this feeling--Have an interest in keeping it up--Strongest in the Free States--Several instances of its nature and extent--Circumstance exhibiting a striking contrast in favour of the Sable race--Further effects of prejudice-- Public opinion on this subject very strong in the United States. - CHAPTER VIII.--PAGE 92.

Result of the idea of inferiority in the Negro race a prolongation of their oppression--Unequal rights and privileges--Their tendency-- Human beings possess certain inalienable rights--All men created equal--Acknowledgment of this great doctrine in the American Declaration of Independence--Slavery a stain on the glory of America-- A lie to the Declaration of the Federal Constitution--Columbia may yet redeem her character--No new laws required--Only that all should be placed on an equality--No exemption of the Negro from law, but should enjoy its protection--Observations on equitable laws --Justice always the truest policy--America called to a great and noble deed--Address to Columbia. - CHAPTER IX.--PAGE 99.

Pernicious influence of Slavery--Those brought up in the midst of it unconscious of its evils--Deceptiveness of the "SLAVERY OPTIC GLASS"--The products and gains of oppression tainted--Nothing can sanction violence and injustice--To prosper by crime, a great calamity--Melancholy situation of those implicated in Slavery-- Plea of the necessity of coercion--Negroes represented as most

Page xxdegenerate and ungovernable--This accounted for--Demoralizing effects of Slavery--When its asperities have been mitigated, various latent virtues and good qualities have been brought into exercise.

- CHAPTER X.--PAGE 105.

To form a just estimate of the Negro character, we must observe him under more favourable circumstances than those of Slavery--Statements of Travellers who have visited Africa, describing the natives as virtuous, intelligent, &c.--Their ingenuity--Clarkson's interview with the Emperor of Russia--His surprise at their proficiency-- Wadstrom's testimony before the House of Commons--Many other testimonies--Dr. Channing says, "we are holding in bondage one of the best races of the human family." - CHAPTER XI.--PAGE 120.

The African race examined in an Intellectual point of view--Their origin and noble ancestry--Ethiopians and Egyptians considered--Negroes have arrived at considerable intellectual attainments, and have distinguished themselves variously--Exemplified in Amo--State of learning at Timbuctoo in the sixteenth century--Many other instances of their intellectual attainments--Further testimony of Blumenbach to their capacity for scientific cultivation--Corroborative evidences--Demonstration of Negro capabilities in living witnesses-- The highest offices of State in Brazil filled by Blacks-- Coloured Roman Catholic Clergy--Lawyers--Physicians--Dr. Wright's testimony to the capabilities and intellect of the Negro. - CHAPTER XII.--PAGE 144.

The foregoing facts afford unquestionable evidence of the capabilities of the Negro--Their desire for improvement--Obstacles to this--Invidious distinctions--Effects of Slavery--The improvidence, indolence, &c., ascribed to the Negro, considered--Testimony of Dr. Lloyd-- Similar charges brought against the ancient Britons--Russians a century ago--Admitting every thing in favour of distinct races, all are capable of great improvement--Events in St. Domingo--Improvement in Negroes brought to Europe--Comparisons--Effects of Education, &c.--Fact related by Dr. Horn--White races liable to relapse into barbarism--Instances of retrogression in Whites--The Greeks and Romans--Case of Charlotte Stanley--Civilization a vague and indefinite term--Remarkable instance of retrogression in America-- Progression in the Negro defended on the same ground--Time required-- Accelerated in proportion as impediments are removed.

Page xxi - CHAPTER XIII.--PAGE 162.

Refutation of the plea of coercion being necessary for the Negro--Palliated by representing him as deficient in the finer feelings --This also refuted --Testimony of Captain Rainsford--Remarks of Dr. Philip--The Negro represented to be under a Divine anathema--Observations of Richard Watson on this subject--Refuted on Christian grounds-- All tribes stretching out their hands unto God--Results of missionary labours--Facts concerning the progress of the Negro in virtue and religion--Instances illustrative of the highest religious susceptibilities--Testimony of a Wesleyan Missionary--Such evidences very conclusive--Beautiful remarks by Richard Watson. - CHAPTER XIV.--PAGE 173.

Slavery considered--A violation of the rights of Man--Remarks of Milton--Condemned by Pope Leo X. --Remarks of Bishop Warburton--How can Christians continue to be its upholders?--Guilt of Britons and Americans--Expiation of our sin by a noble sacrifice--We can never repay the debt we owe to Africa--White Man instilling into those he calls "savages" a despicable opinion of human nature-- We practice what we should exclaim against--No tangible plea for Slavery--Criminal to remain silent spectators of its crimes--We cannot plead ignorance--Seven millions of human beings now in Slavery--Four hundred thousand annually torn from Africa-- Slavery a monstrous crime--A robbery perpetrated on the very sanctuary of man's rational nature--A sin against God--America's foul blot--Slaves represented as happy--Remarks on this. - CHAPTER XV.--PAGE 181.

Sources of the calumnious charges against the Negro--Their character only partially represented--Applicable remarks of Plutarch--Perverted accounts of travellers to be guarded against--Opportunities of actual observation limited--Importance of authentic facts--They prove that all mankind are equally endowed, irrespective of Colour or of clime--Compassion for a sufferer heightened by youth, beauty, and rank--As in Mary, Queen of Scots--No incompatibility between Negro organization and intellectual powers--To demonstrate this the design of the work--The author, in selecting instances for this purpose, has been more thoroughly impressed with its truth--Negroes only require freedom, education, and good government, to equal any people--Expression of sympathy for the oppressed race of Africa.

Part First.

Page xxii

- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF AFRICANS, OR THEIR DESCENDANTS; WITH TESTIMONIES OF TRAVELLERS, MISSIONARIES, &c. RESPECTING THEM.

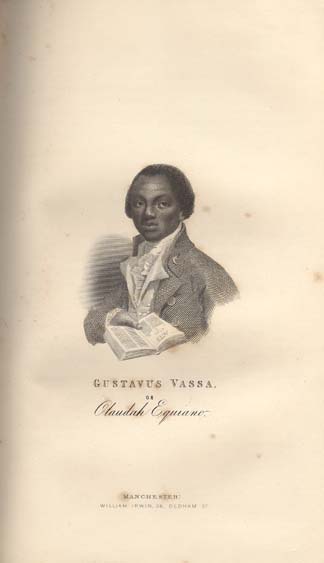

- OLAUDAH EQUIANO, or GUSTAVUS VASSA . . . . . His Narrative . .

. . .

19

Dedicates his Narrative to the British Parliament--Stolen from Africa--Sent to Virginia, and sold into Slavery--Purchases his freedom--Remains in his master's service--Voyage to Montserrat, Georgia, &c.--Obtains his discharge--Sails for London--Accompanies an expedition to explore a North-West passage --Religious impressions--Incidents connected therewith--Voyage to Cadiz--Further Religious impressions--Perilous situation in a second voyage to Cadiz --Providential deliverance--Accompanies Dr. Irving to Jamaica--Sails for Europe again--Grievously imposed upon--Arrives in England--Enters into the service of Governor McNamara--Proposal for him to go out as a Missionary to Africa--Memorial to the Bishop of London--The Bishop declines to ordain him--Sails for New York--Returns to London--Sails for Philadelphia--With other Africans, presents an address of thanks to the Quakers in London--Appointed a Government Commissary in an expedition to Sierra Leone--Incidents connected therewith--Memorial to the Lords' Commissioners of the Treasury-- Presents a Petition to the Queen--Concluding remarks to his Narrative. - JOB BEN SOLLIMAN; an African Prince . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 239

- SADIKI; a Learned Slave . . . . . Madden's West Indies . . . . . 241

Redeemed by Dr. Madden--Writes a history of his life in Arabic. - TESTIMONY OF CAPTAIN PILKINGTON . . . . . Particular Providence . . . . . 249

Intelligent Free Blacks at Sierra Leone--The Timini, Sooso, and Mandingo Nations--The Kroomen. - PLACIDO . . . . . The Heraldo," &c. . . . . . 252

A Slave of great natural genius--Seized for Conspiracy--His great fortitude--Composes a beautiful Poem--Recites it when proceeding to execution. - THE HAPPY NEGRO . . . . . Andrew Searle's Life . . . . . 256

His remarkable religious experience. - RICHARD COOPER . . . . . Society of Friends . . . . . 259

- TESTIMONY RESPECTING THE BUSHMEN . . . . . Philip's Researches

. . . . . 261

With several interesting examples. - ANTHONY WILLIAM AMO; a Learned Negro . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 265

Studies at Halle--Skilled in several Languages--Publishes Dissertations, &c., in Latin--Made a Doctor of the University of Wittemburg--And Counsellor of State by the Court of Berlin. - TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE . . . . . Biog. Universelle, &c.. . . . . 267

Born a Slave in St. Domingo--Of thorough Negro descent--His good qualities

Page xxiiiobtain kind treatment--Accidental acquirement of knowledge--Insurrection of the Negroes of St. Domingo--Toussaint refuses, for some time, to take part in it--Finally joins the revolt--Noble conduct in first securing the safety of his master and family--After various struggles, becomes Commander in Chief of the French forces--Prosperity of the Island under his command--Anecdote characteristic of his integrity--Assumes the title of President--Forms a new Constitution--The excellencies of his character unfolded--His remarkable activity--Description of him by one of his enemies--Captain Rainsford's remarks respecting him--Incident exemplifying his integrity--Attains the highest of his prosperity--Buonaparte's alarm--Sends an expedition to St. Domingo-- Slaughter of Blacks--Affecting incidents--Toussaint arrested by treachery--Taken captive to France--Imprisoned and destroyed by severe treatment-- Undoubtedly a remarkable man.

- SUBSEQUENT HISTORY OF ST. DOMINGO . . . . . Facts of History . . . . . 299

Dessalines, Christophe, and Petion, successive Negro Governors--Social condition of. - NOTICE OF A SON OF TOUSSAINT . . . . . Irish Friend . . . . . 306

- GEOFFREY L'ISLET . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 307

A Mulatto Officer of Artillery--Correspondent of the French Academy of Sciences--Executes Maps and Plans, and keeps a Meteorological Journal--Versed in Botany, Natural Philosophy, Zoology, and Astronomy. - KAFIR GENEROSITY . . . . . Pringle's African Sketches . . . . . 308

- T. E. J. CAPITEIN . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 309

A Negro born in Africa--Brought to Europe, and educated in Holland--Studied languages, &c., at the Hague--Took his degrees, and returned as a Christian Minister to Africa--Writes an Elegy in Latin--Publishes Dissertations, &c. - CHRISTIAN KINDNESS IN AN AFRICAN . . . . . Moffatt . . . . . 312

- OTHELLO . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 313

Writes an eloquent Essay against the Slavery of his race. - JAMES DERHAM . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 315

Originally a Slave--Becomes one of the most distinguished physicians at New Orleans - ANECDOTE OF TWO NEGROES IN FRANCE . . . . . Mott's Sketches . . . . . 315

- KINDNESS OF A COLOURED FEMALE . . . . . History of Hayti . . . . . 317

- THOMAS JENKINS; an African Prince . . . . . Chambers's Miscellany . . . . . 317

Sent to England by Captain Swanston to educate--The Captain dying, the Negro is thrown on the world--Eager pursuit of knowledge--Instructs himself in Latin and Greek--His religious impressions--Offers himself as a school-master--Examined and accepted--Difficulties from prejudice against colour--Final success--Spends a winter at college--Goes as a Missionary to the Mauritius, and attains eminence as a teacher. - NOTICE OF AN INTELLIGENT NEGRO . . . . . Captain Wauchope, R.

N. . . . . . 323

- NEGRO CHARACTER AND ABILITY . . . . . Captain Wauchope, R. N. . . . . . 324

- HOSPITABLE NEGRO WOMAN . . . . . Park's Travels . . . . . 327

Her kindness to the weary traveller--Song composed by Negroes extempore--Beautifully versified--Remarks by Dr. Madden. - ATTOBAH CUGOANO . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 329

Born in Africa and stolen for a Slave--Liberated by Lord Hoth--An Italian author praises this Negro--His piety, modesty, integrity, and talents--Publishes Reflections on the Slave Trade.

Page xxiv - WILLIAM HAMILTON . . . . . Sturge & Harvey's W. Indies. . . . . . 331

Formerly a Slave in Jamaica--Suffers for attending a place of worship--Learns to read and write by stealth--Keeps a journal--Purchases his freedom for £209. - PHILLIS WHEATLEY . . . . . Her Works . . . . . 332

A Negress stolen from Africa and sent to Boston--Bought by a lady to attend her in old age--Exhibited extraordinary intelligence--Soon learned to read and write--Became an object of astonishment--Her literary acquirements--studied Latin--Wrote and published thirty-nine poems--Several specimens of her poetical talent--Is liberated--Visit to England--Moved in first circles of society--A proof of what education can effect in the Negro. - JOHN KIZELL . . . . . Anecdotes of Africans . . . . . 348

A Negro--Taken as a Slave to Charlestown--Sent to Sierra Leone, and employed in negociations with native Chiefs. - BENJAMIN BANNEKER . . . . . Abbé Grégoire et Passiom . . . . . 350

Of pure African descent--Makes astronomical calculations--And publishes almanacs at Philadelphia--His letter to the President of the United States--The President's answer. - FAITH OF A POOR BLIND NEGRO . . . . . Mott's Biog. Sketches . . . . . 356

- A PIOUS AND ENLIGHTENED KAFIR . . . . . Philip's Researches . . . . . 356

- INTELLIGENT AND ELOQUENT KAFIR CAPTIVE FEMALE . . . . . Pringle's Researches . . . . . 357

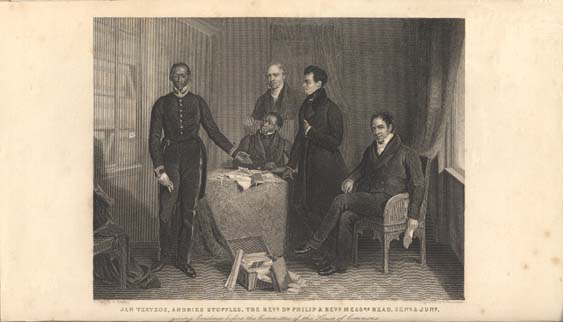

- JAN TZATZOE; a Christian Kafir Chief . . . . . Christian Keepsake . . . . . 359

His parentage--Is received into the Missionary School at Bethelsdorp--Strong religious impressions--Travels with the Missionary Williams--Acts as interpreter to Lord Somerset--Renders valuable aid in establishing the Mission at Wesleyville--Restrains his tribe from war--Deprived of his hereditary lands, and driven into the wilderness--With Andries Stoffles, a Hottentot, visits Great Britain to procure compensation, and to solicit assistance in promoting the moral and spiritual improvement of his countrymen--Notorious facts--Examined before a select Committee of the House of Commons--Extracts from the printed evidence--Very explicit and conclusive--Address of Stoffles at Exeter Hall--Testimony of E. Baines, M. P., on the occasion--Restitution awarded him--Returns to Africa--Visited by James Backhouse--High testimony respecting him--Lines by T. Pringle. - ANDRIES STOFFLES; a Christian Hottentot . . . . . Missionary Magazine, 1838. . . . . . 374

His early life and conversion--Testifies of the Grace of God to his countrymen--His impressive manner--Imprisoned for preaching--Preaches to his fellow-prisoners--His valuable assistance to Missionaries--Formation of the settlement of Kat River--Embarks for England--His eloquent and animated addresses--His health declines and he returns to Africa--His happy death--His personal appearance. - EXTRACT OF A LETTER FROM JOHN CANDLER . . . . . Irish Friend . . . . . 380

- GRATEFUL SLAVES . . . . . Madden's West Indies . . . . . 381

- SIMEON WILHELM . . . . . Bickersteth's Memoir . . . . . 382

Born in Africa--Received into the Missionary School at Bashia--His teachable, gentle, and affectionate disposition--Accompanies E. Bickersteth to England--His education under the Vicar of Pakefield--His health suffers--High testimony respecting him--Makes considerable progress in learning Arabic--Begins Latin--Powerful influence of Divine Grace exemplified in him--His decease. - LOUIS DESROULEAUX . . . . . Raynal's European Set. . . . . . 387

Page xxvA confidential Slave--Purchases his freedom--Remarkable gratitude to his former master.

- PRINCE GAGANGHA ACQUA . . . . . Communicated . . . . . 388

A son of an African King--After some singular incidents he arrives in England--Meets with kind friends in London--His admiration and astonishment in viewing the metropolis--Highly appreciates European knowledge--His account of the mode of procuring Slaves--Gradations by which intelligence occupied his former ignorance and superstition--Visit to the British Museum--Progress of his religious acquirements--Introduced to Lord John Russell and T. F. Buxton--The latter presents him with a writing case--The inscription upon it--His sense of the evils of Slavery--Scientific men much admired the organic structure of his head--Returns to Africa--Subsequent gratifying particulars respecting him. - BENOIT THE BLACK . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 397

Eminent for an assemblage of virtues. - BENJAMIN COCHRANE . . . . . Madden's West Indies . . . . . 397

A skilful Negro Doctor in Jamaica--Learned Mandingo Negroes--A Koran written from memory by one of them. - ROSETTA . . . . . Anti-Slavery Reporter . . . . . 399

A remarkable Narrative, evincing that the Negro character is not devoid of humanity or magnanimity when fairly tested. - DISINTERESTED TESTIMONY TO NEGRO

ABILITY AND FAITHFULNESS . . . . . Robert Jowitt . . . . . 404

- ALEXANDRE PETION . . . . . Bedchamber's Biog. Dic. &c. . . . . . 405

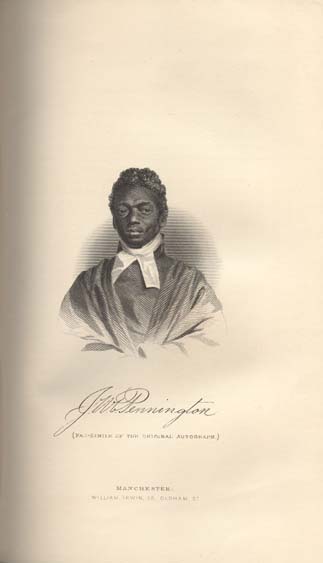

A dark Mulatto--President of Hayti--Educated in the Military School of Paris--A skilful engineer--A man of fine talents--Unfortunate in his government--Candler's testimony respecting him--Interesting and pleasing anecdote. - JAMES W. C. PENNINGTON . . . . . Communicated . . . . . 406

Minister of a Presbyterian Church in New York--A fugitive from Slavery--His birth and parentage--Escapes from Slavery--Sheltered at the house of a Quaker in Pennsylvania--Who gives him some instruction--Teaches a school near Flushing--Religious impressions--Desires to become a minister--Studies at the Theological Seminary at New Haven--Preaches eight years at Hartford-- Elected to a seat in various Conventions--Deputed to attend at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London; also the World's Peace Convention--Takes part in them--Preaches in many chapels in England--Supplies the pulpits of some of the most popular ministers--Favourably received on his return to America--Presides over an assembly of Whites--Examines candidates in Church History, Theology, &c.--His publications--Refutes calumny before a large audience of Whites. - IGNATIUS SANCHO . . . . . His Life and Letters . . . . . 410

Born on board a Slave-ship--Taken to England and presented to three ladies--The Duke of Montague admires and takes an interest in him--On the death of the Duke the Duchess admits him into her household--Marries and commences business--Gains the public esteem--Applies himself to study--His reputation as a wit and humourist--Two volumes of his letters published-- Exhibit considerable epistolary talent, rapid and just conception, and universal philanthropy--Extracts from several of them--Interested in the unfortunate Dr. Dodd--Writes on his behalf--Addresses Sterne--Sterne's reply--Concluding observations. - EVA BARTELS . . . . . Shaw's South Africa . . . . . 425

A Mulatto woman of South Africa--Her conversion--An example of piety--Zealous in inviting and bringing others to grace.

Page xxvi - JOHN MOSELY . . . . . Hartford Courant . . . . . 426

Well known for industry, prudence, and integrity--Devotes his property to charitable objects. - NANCY PITCHFORD . . . . . Hartford Courant . . . . . 427

- LOTT CAREY . . . . . Mott:--Chambers . . . . . 427

Born a Slave in Virginia--Excessively profane--Becomes awakened--Learns to read and write--His business abilities--Often rewarded with presents--Saves 850 dollars, and purchases his freedom and that of two of his children--Afterwards of his family--Purchases land in Richmond--Devotes his leisure to reading--Interest in African Missions--Goes out to Sierra Leone--Substance of his farewell sermon--Death of his second wife--Wide field of usefulness--His great abilities place him in a station of influence--Description of him by an American writer--Relieves the sufferings of the early emigrants--Makes liberal sacrifices of property and time--Acts as physician--Made health Officer and General Inspector--His melancholy death from an explosion--Proof that Blacks are not destitute of moral worth and innate genius. - TESTIMONY OF JOSEPH STURGE . . . . . Communicated . . . . . 431

Respecting the Intellectual Powers of the Negro--Comparison between Black or Coloured and White children. - CORNELIUS . . . . . Holme's Moravian Missions . . . . . 433

A Negro assistant Missionary in St. Thomas--His conversion and progress in religion--Christian address to his children on his death bed. - MORAVIAN MISSIONS . . . . . Oldendorp . . . . . 436

Amongst the Negroes of the West Indies--Opposition to the conversion of the Negroes--Visit of Count Zinzendorf--He returns to Europe--His appeal to the Danish Government--Negroes addresses to the King and Queen of Denmark--The Count takes one of the Negroes to visit the German Churches--Particulars respecting David, Abraham, and others of the Black assistant Missionaries--Susanna Jaos--Peter and Abraham--Their evangelical discourses--Abraham's melancholy death--His steadfastness. - INTELLIGENT AFRICANS . . . . . Evidence Before Select Com. . . . . . 441

- A NEGRO SLAVE AND POET . . . . .His Life by Dr. Madden . . . . . 442

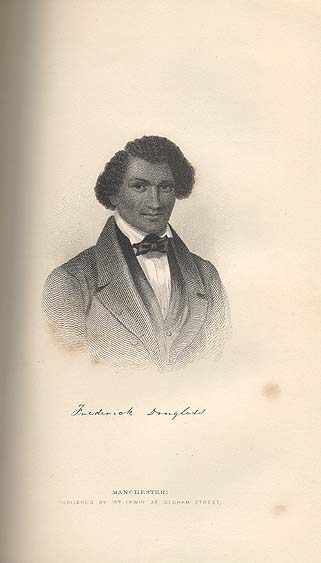

Composes verses at the age of twelve--Cruel treatment--Made a mere automaton--Learns to draw--Melancholy events--His sufferings--Trust in God--Treated with greater kindness--Pursuit of knowledge under difficulties--Effects his escape from Slavery--Specimens of his Poems translated from the Spanish--To Calumny--Religion--The Firefly--The Dream, &c. - FREDERICK DOUGLASS . . . . . His Narrative . . . . . 454

Born a Slave--Effects his escape--Writes his Narrative--Remark on it--His feelings at the chance of being one day free--His intellectual capabilities--An eloquent public speaker. - NEGRO CHARACTER AND ABILITY . . . . . Dr. Winterbottom . . . . . 457

Dr. Winterbottom's opportunities of observing Negro character in Africa--Their benevolence and hospitality--Mental powers--Some extremely intelligent. - SUANA; a Kafir Chief . . . . . Philip's Researches . . . . . [458]

An enlightened Christian--His happy death--Was a poet--Specimen of his abilities--Translation. - JASMIN THOUMAZEAU . . . . . Mott's Biographical Sketches . . . . . 460

Born in Africa--Sold as a Slave to St. Domingo--Obtains his freedom--Establishes a Hospital for Negroes--Medals decreed to him. - PAUL CUFFE . . . . . Memoir by W. A. . . . . . [460]

An intelligent, enterprising, and benevolent Negro--His father stolen from

Page xxviiAfrica--Sold into Slavery--Purchases his freedom and a farm of 100 acres--Paul pursues knowledge under difficulties--His natural talents--Petition the Legislature on behalf of the Free Negro population--They receive equal privileges in consequence--Increases his property--Owns vessels, houses, and land--Anecdote illustrative of prejudice--His good conduct removes it--Establishes a public school at his own expense--Joins the Society of Friends--Becomes a preacher amongst them--Teaches Navigation--His integrity--Mourns over the condition of his African brethren--Visits Sierra Leone--Suggests improvements in the colony--Institutes a Society for promoting the interests of its members and the colonists--Epistle issued by it--He visits England at the invitation of the African Institution--Good conduct of the Coloured crew at Liverpool--African Institution acquiesce in Paul's plans--Authorize him to carry Free Negroes from America to Sierra Leone to instruct the Colonists--Visits Sierra Leone again--Thence to America--His joyful welcome there--Could not rest at ease whilst thinking of the sufferings and degradation of his fellow-creatures-- Prepares for another voyage to Sierra Leone--Presented by the American war--Improves and matures his plans--sails with 38 Africans to Sierra Leone--Proof of his zeal for the welfare of his race--Expends from his private fundsb 4000 dollars for the benefit of the Colony--Grant of land from the Governor--Paul's address to the Negroes--His final departure for America--An affecting scene--Seized with a complaint which proves fatal in 1817--Sketch of his character by Peter Williams--His remarkably happy close--Testimony of an American paper--Concluding remarks.

- EXTRACT OF A LETTER FROM MARYLAND . . . . .The Friend . . . . .

476

Respecting two liberated slaves--Remarkable proofs of their gratitude. - ASHTON WARNER . . . . . His Narrative . . . . . 477

A Slave in St. Vincent's--His freedom purchased by Daphne Crosbie, a benevolent Negress--he is re-enslaved--Asserts his independence--Makes his escape--Arrives in England, and writes his Narrative--Though uneducated, very intelligent--Destitution and the climate prove fatal--Dies in London--His remarks on slavery--Testimony respecting him. - ALEXANDER CRUMMELL . . . . . Communicated . . . . . 479

Of pure African parentage--One of the only four episcopal Coloured clergymen in the United States--Remarkable example of what the African can become by cultivation--Extracts from his Eulogy on the Life and Character of Clarkson--Abounds in pathos and rich touches of eloquence--Visits England--Addresses meeting of Anti-Slavery Society--Preaches in St. George's Church, Everton-- Particulars of this occasion--Sketch of his sermon--A living proof of the capability of the African. - ANECDOTE ILLUSTRATIVE OF FAITHFULNESS . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 490

- MAROSSI; THE BECHUANA BOY . . . . . Pringle's African Sketches . . . . . 491

An orphan boy, ten years of age, stolen by banditti--Falls under Pringle's protection--His affecting story immortalized by Pringle, in a beautiful and touching poem--Accompanies Pringle to England--An interesting and remarkable youth--His religious feelings--His death. - EXTRAORDINARY FIDELITY OF A NEGRO BOY. . . . . .Irish Friend . . . . . 496

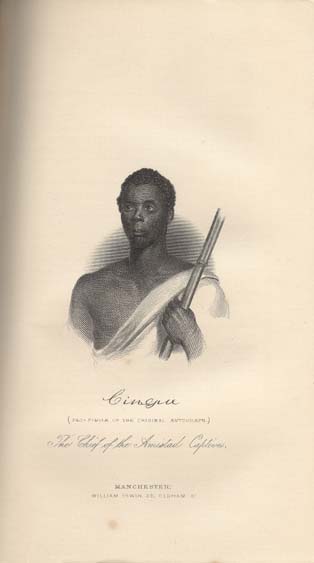

- THE AMISTAD CAPTIVES . . . . . Sturge's United States, &c.. . . . .497

Africans from the Mendi country--Overcame the crew of the Slaver--The vessel brought into Newhaven--They are lodged in jail--Interest excited in their behalf--Their cruel treatment--Finally become liberated--Their progress in

Page xxviiilearning--Their excursion through the States--Impression made--Fund raised to convey them home with Missionaries--Cinque--A remarkable man--Sturge's account of these Africans--Their superior intellect--Belief in a Supreme Being--Embark for Sierra Leone.

- TESTIMONY OF DR. THOMPSON . . . . . Parliament. Report . . . . . 502

- LLEWELLYN CUPIDO MICHELLS . . . . . James Backhouse . . . . . 503

A descendant of a Hottentot chief--Received into a Missionary School--His amiable disposition--Early religious impressions--Brought to England to educate--Enters the family of James Backhouse--His health declines rapidly--Influence of divine grace exemplified in him--His happy close. - THE GRATEFUL NEGRO . . . . . Mott's Biog. Sketches . . . . . 505

- THE FAITHFUL NEGRESS . . . . . Idem . . . . . 506

- FRANCIS WILLIAMS . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 507

Born of African parents in Jamaica--Duke of Montague struck with his talents--Sent to England to educate--Publishes a poem--Returns to Jamaica--Teaches a School--Composes poems in Latin--A specimen of one addressed to the Governor of Jamaica--Translated into French by Abbé Gregoire--into English by Long, and versified--Just observations of the Dean of Middleham. - HENRY H. GARNETT . . . . . Communicated . . . . . 510

Born in Maryland--Descended from an African chief--Escapes with his family from Slavery--Hunted by men stealers--Becomes a cabin boy on board a schooner--Enters the African Free School at New York--Admitted into Canal Street Collegiate School--Studies Latin--Enters Canaan Academy--Events there--His marriage--Religious impressions--Turns his attention to the gospel ministry--Gains reputation at the Oneida Institute as a courteous and accomplished man, an able and eloquent debater, and a good writer--Appears as a public speaker--Graduates at Whitestoun, and receives his diploma--Ordained a minister at Troy--Obtains a hearing before the legislatures of New York and Connecticut--His remarkable speeches--Publishes a Discourse on the Past and Present Condition, and Destiny of the Coloured Race--Connected with a newspaper--He is a pure Black. - SOLOMON BAYLEY . . . . . Narrative and Letters . . . . . 513

Robert Hurnard interested in obtaining and publishing his Narrative--Prevails upon him to write it--Account of his early life--Born a Slave--Various trials and difficulties--His deep religious impressions--His growth in the truth beautifully narrated--A few of his letters--His call to the ministry--Visits Liberia--Returns to America again--Just observation of Clarkson after reading the Narrative of this pious Negro. - HANNIBAL, OR ANNIBAL . . . . . Abbé Grégoire . . . . . 523

A well-educated Negro--Becomes a lieutenant general and director of artillery in Russia--His talented son--commenced the establishment of a fort and fortress at Cherson. - FACTS FROM LIBERIA . . . . . Colonization Herald . . . . . 523

Remarkable exhibition of Negro capability in Liberia, a colony of free negroes --Their sound judgment and Christian character--Christian government--a purely moral community--Public school--Religion and morality progressing-- Exclusion of ardent spirits--Improvement--The Governor J. J. Roberts, a Slave in Virginia a few years ago--His superior character and ability--Extract from his Inaugural address--Hilary Teague, a Coloured senator--The son of a Virginian Slave--Extracts from an eloquent speech made by him, embracing a most beautiful exposition of the history, trials, exertions and

Page xxixaspiration of the Negro colonists--The abettors of Slavery challenged to exhibit half the talent and ability evinced in the addresses of these Coloured legislators.

- JOANNES JAAGER . . . . . Shaw's Memorials . . . . . 534

A South African--His conversion--Very desirous of instruction--His progress in knowledge--Zeal--Travels with Missionary Threlfall--Courage in danger-- A martyr to the Truth--Lines on the occasion, by Montgomery. - TESTIMONIES OF HANNAH KILHAM . . . . . Her Life . . . . . 526

- A NOBLE SLAVE EMANCIPATED . . . . . Gazette Officielle . . . . . 538

- EUSTACE . . . . . Chambers' Journal . . . . . [539]

A remarkably benevolent and intelligent Negro, born in St. Domingo--Definition of the characteristics of his life by a Phrenologist--Saves his master's life and many hundreds besides--Rescues the former from danger--They sail together to America--Succours unfortunate sufferers at Baltimore--His liberation--Subsequent devotedness--Saves his master's life again--Death of the latter--Eustace's remarkable benevolence--Accompanies General Rochambeau to England and France--Kindness to a poor widow--French academy grant him a prize--Worthy of a noble monument. - WILLIAM WELLS BROWN . . . . . His Narrative . . . . . 541

Escapes from Slavery--Harrowing scenes portrayed in his Narrative--Befriended by a Quaker--Assists his fugitive brethren in Canada--His abilities evinced in an article written by him on the Slave Trade. - A MASS OF FACTS demonstrative of Negro capability remain in

the Author's hands--a few claim a passing notice--ZHINGA, a

Negro Queen--BE SENIERA, King of Kooranko--ASSANA

YEERA, a Negro King--JEJANA, a South African Widow--

LUCY CARDWELL--JOSEPH RACHEL--JOHN WILLIAMS--JACOB LINKS--PETER LINKS--ZILPHA MONJOY--ALICE a female Slave--GEORGE HARDY--QUASHI--MOSES, a Negro of Virginia

--ZANGARA--CHARLES KNIGHT--JOSEPH MAY--MAQUAMA--JACOB HODGE--THE NEGRO SERVANT--BELINDA LUCAS--AFRIKANER--JUPITER HAMMON--ANGELO SOLIMANN . . . . . from 545

- LIVING WITNESSES, demonstrative of Negro capability . . . . . 550

- JOSEPH THORNE . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 550

Born a Slave--Remained one till twenty years of age--Now a lay preacher in the Episcopal Church--His accomplished wife and family. - THOMAS HARRIS . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 551

Thome and Kimball's account of a visit to his family--Interesting conversation--Lively discussions--Their equality with Whites--Facts respecting T. Harris--Born a Slave--His business talents--Eminently distinguished by manly graces and accomplishments. - S. A. PRESCOD . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 553

A young Coloured gentleman--Educated in England--Editor of a Newspaper--Debarred from filling various offices--Excluded from the Society of Whites--Dr. Lloyd's observation respecting him. - MR. JORDAN . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 554

Improvement of Coloured people in Jamaica--Are Aldermen--Justices ofPeace, &c.--Mr, Jordan is a member of the Assembly--Owns the largest book store in Jamaica, and an extensive printing office, issuing a paper twice a week--Other papers issued by Coloured people--Many Coloured printers.

Page xxx - RICHARD HILL . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 555

A Coloured gentleman of very superior abilities--Secretary of the special magistrate department of Jamaica--Member of the Assembly--High testimony respecting him--Travels two years in Hayti--His published letters written in a flowing and luxuriant style--Secretary to the Governor and main-spring of the Government during administration of Lord Sligo and Sir Lionel Smith--A naturalist--Has recently published a valuable ornithological work. - LONDON BOURNE . . . . . Thome and Kimball . . . . . 557

Interesting account of a visit to his family--Genuine Negroes--Their intelligence--Mr. Bourne a Slave till 23 years old--His freedom purchased by his father for 500 dollars--And his mother and four brothers for 2500 dollars--Has become a wealthy merchant--Highly respected for his integrity and business talents--Many other Coloured persons and families of equal merit as those named--Some are popular instructors, and one ranks high as a teacher of languages. - CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS . . . . . 560

Part Second.

Page xxxi

List of Portraits and Engravings.

- The Africans, Tzatzoe and Stoffles, giving evidence before a Committee of the British Parliament (for further description see page 365) . . . . . Facing Title.

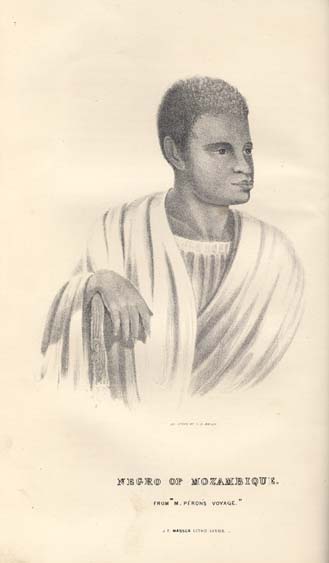

- A Negro of Mozambique (from M. Peron's Voyages) . . . . . 43

- Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa . . . . . 192

- Toussaint L'Ouverture, the Black Chief of St. Domingo . . . . . 278

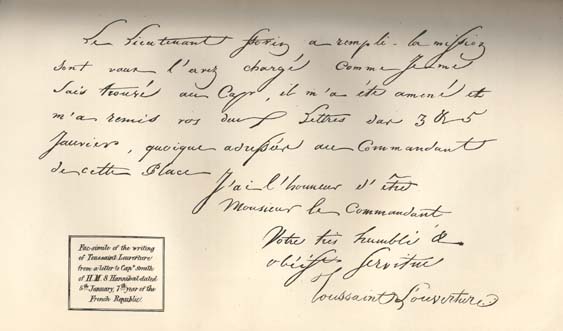

- Fac simile of Toussaint's Hand Writing . . . . . 286

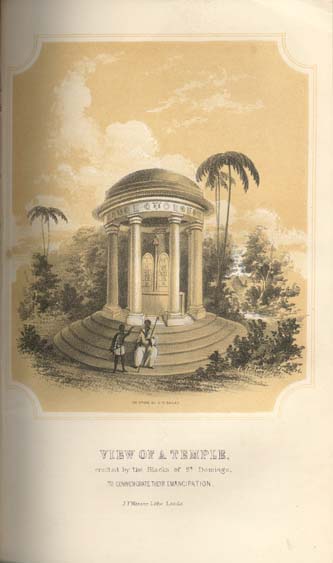

- Temple erected by the Blacks of St. Domingo to commemorate their Emancipation . . . . . 304

- Jan Tzatzoe, a Christian Chief of South Africa . . . . . 359

- James W. C. Pennington, born a Slave; a highly esteemed Gospel Minister . . . . . 408

- Frederick Douglass, a fugitive Slave . . . . . 456

- Cinque, the Chief of the "Amistad Captives" . . . . . 500

- THE MOROCCO COPIES ALSO CONTAIN, IN ADDITION TO THE ABOVE, THE FOLLOWING ENGRAVINGS ON STEEL:

- Gang of Slaves journeying to be sold in a Southern Market . . . . . 542

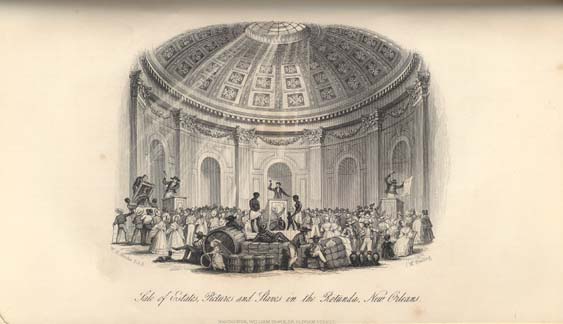

- Sale of Estates, Pictures, and Slaves, in the Rotunda, New Orleans . . . . . 544

Page xxxiii

INTRODUCTORY POEM:

BY

BERNARD BARTON.

A TRIBUTE for the Negro Race!

With all whose minds and hearts

Have known the power of Gospel Grace,

The love which it imparts.

Who know and feel that God is Love!

And that His high behest,

Given from His throne in Heaven above

Says--"Succour the oppress'd!"

A TRIBUTE for our Brother Man!

Our Sister Woman too!

With all whose feeling hearts can own

What unto each is due:

Who cherish holy sympathy

With human flesh and blood,

And feel the inseparable tie

Of that vast Brotherhood!

Page xxxiv

That the same God hath fashion'd all,

Moulded in human frame;

And bade them on His mercy call,

Pleading--A Father's Name!

That the same Saviour died for each,

So each to Him might live!

That the same Spirit sent to teach,

To ALL can Wisdom give.

A TRIBUTE to the mental power

Of Blacks, as well as Whites;

For Nature, in her ample dower,

Owns all her Children's rights:

And scorns, by casual tint of skin,

Those sacred rights to adjust,

Which, to the immortal Soul within,

Her God hath given in trust!

A TRIBUTE to fair Freedom's spells,

The boon of God on high;

For--ever--where His Spirit dwells,

There must be Liberty!

That Spirit breaks each galling yoke--

Fetters of cruel thrall,

The brand's impress, the scourge's stroke,

It loathes, laments them all.

Page xxxv

Lastly,--A TRIBUTE unto HIM,

OUR FATHER! throned in Heaven!

For all who yet, in life or limb,

Succumb to Slavery's leaven.

That He for such His arm may bare,

Their Liberator be;

And in His Will and Power declare

"The Negro shall be free!"

That as His mighty, outstretch'd hand

Led Israel forth of yore,

So He to Afric's injured land

Would Freedom--Peace restore.

That Gospel Love, and Gospel Grace,

May there His Power proclaim;

Make glad each solitary place,

And glorify His Name!

Page 2

A Tribute for the Negro.

PART I.

An Inquiry into the claims of the Negro

Race to humanity, and a Vindication of

their original equality with the other

portions of Mankind; with a few

observations on the inalineable rights of

Man, the sin of Slavery, &c., &c.

Page 3

CHAPTER I.

AN INQUIRY INTO THE CLAIMS OF THE NEGRO RACE TO HUMANITY, &c.

Sin of Slavery increasingly acknowledged--Delusion respecting the moral and intellectual capacity of the Negro--An important question--To despise a fellow-being on account of any external peculiarity, a sin-- Christianity the manifestation of universal love--Inquiry into the causes of the diversity characterising various nations and people--Analogous in animals--Remarks of Buffon and Lawrence on this subject--Connection between the physiological, moral, and intellectual characters in Man--The diversities trifling in comparison with those attributes in which they agree--Nothing to warrant us in referring to any particular race an insurmountable deficiency in moral and intellectual faculties-- Scripture testimony to unity of origin in the human race.

In the present enlightened age, talent and piety have combined their energies, in endeavouring to promote the welfare and emancipation of the degraded and enslaved African. The grievous sin of man making merchandise of his fellow-creatures, and holding them in perpetual slavery, has long been a subject of eloquent declamation, and has for some time been denounced by the unanimous voice of the British public. England has given to the nations a noble example, in abolishing, at a great sacrifice, a system of injustice and cruelty, in which she had long taken a guilty part.

" 'Twas Britain's mightiest sons that struck the blow!"

"And monarchs trembled at the o'erpowering sound,

And nations heard, and senates shook around,

And widely struck, by the victorious spell,

From Negro limbs, the enslaving shackles fell!"

Page 4

Yet notwithstanding the evils of Slavery are becoming increasingly felt and acknowledged, it is evident that there still exists, in the minds of many who deprecate the whole system as unjust, a strong delusion with regard to the moral and intellectual capacities of the Coloured portion of mankind, and as regards their proper station in the scale of intelligent existence.

It is an important question, whether the Negro is constitutionally, and therefore irremediably, inferior to the White man, in the powers of the mind. Much of the future welfare of the human race depends on the answer which experience and facts will furnish to this question; for it concerns not only the vast population of Africa, but many millions of the Negro race who are located elsewhere, as well as the Whites who are becoming mixed with the Black race in countries where Slavery exists, or where it has existed till within a very recent period. Many persons have ventured upon peremptory decisions on both sides of the question; but the majority appear to be still unsatisfied as to the real capabilities of the Negro race. Their present actual inferiority in many respects, comparing them as a whole with the lighter coloured portion of mankind, is too evident to be disputed; but it must be borne in mind that they are not in a condition for a fair comparison to be drawn between the two. Their present degraded state, whether we consider them in a mental or moral point of view, may be easily accounted for by the circumstances amidst which Negroes have lived, both in their own countries, and when they have been transplanted into a foreign land. But if instances can be adduced of individuals of the African race exhibiting marks of genius, which would be considered eminent in civilized European society, we have proofs that there is no incompatibility between Negro organization and high intellectual power.

It has been well observed by a late writer, that it is important to elucidate this question, if possible, on several

Page 5

accounts; and that if it be proved to be correct, the Negro qualified to occupy a different situation in society to that which has been declared to belong to him, by the almost unanimous acclaim of civilized nations. If the capabilities and aptitudes of the Negro are such as some writers argue, he is only fitted, by his natural constitution and endowments, for a servile state; and the zealous friends of his tribe, Wilberforce and Clarkson, Allen and Gurney, with many others, who were thought to have obtained an exalted station among the great benefactors of the human race, must be regarded as having been simply well-meaning enthusiasts, who, under an imagined principle of philanthropy, argued with too much success for the emancipation of domestic animals, of creatures destined by nature to remain in that condition, and to serve the lords of the creation in common with his oxen, his horses, and his dogs. If science has led to this conclusion, as the true and just inference from facts, the sooner it is admitted the better: the opinion which is opposed to it must be unreasonable and injurious.

But the purport of the present volume is to prove from facts which speak loudly, that the Negro is indubitably, and fully, entitled to equal claims with the rest of mankind; --a task by no means difficult, no more so indeed, to the impartial judge, than to demonstrate the self-evident truths

"That smoke ascends, that snow is white."

The claims of the Negro are, however, called in question by

so many, and their rights as men denied by those who point

at the colour which God has given them, with the finger of

scorn, that some counteracting influence seemed desirable.

To despise a fellow-being, or attach a degree of inferiority to him, merely on account of his complexion, or any other external peculiarity which may have been conferred upon him, is to arraign the wisdom of the Allwise Creator, and, consequently, an offence in the Divine sight. "He

Page 6

who cannot recognise a brother," says Dr. Channing, "a man possessing all the rights of humanity, under a skin darker than his own, wants the vision of a Christian." It proves him a stranger to justice and love, in those universal forms by which our benign religion is characterised. Christianity is the manifestation and inculcation of universal love; its great teaching is, that we should recognise and respect human nature in all its forms, in the poorest, most ignorant, most fallen. We must look beneath "the flesh," to "the spirit;" for it is the spiritual principle in Man that entitles him to our brotherly regard. To be just to this is the great injunction of our religion: to overlook this, on account of condition or colour, is to violate the great Christian law. The greatest of all distinctions in Man, the only enduring ones, are moral goodness, virtue, and religion. A being capable of these, is invested by God with solemn claims on his fellow-creatures, and to despise millions of such beings, to stamp them with inevitable inferiority, and to exclude them from our sympathy, because of outward disadvantages, proves, that in whatever we may surpass them, we are not their superiors in Christian virtue.

But when erroneous opinions become thoroughly imbibed, it is difficult speedily, or, perhaps, in some instances, ever, entirely to eradicate them from the mind, however unfounded they may be. Although it is a common, and very just observation, that two individuals are hardly to be met with, possessing precisely the same features, yet there is generally a certain distinctive cast of countenance common to the particular races of men, and often to the inhabitants of particular countries. The differences existing in various regions of the globe, both in the bodily formation of Man and in the development of the faculties of his mind, are so striking that they cannot have escaped the notice of the most superficial observer.

There is scarcely any question relating to the history of organized beings, calculated to excite greater interest,

Page 7

than inquiries into the nature of those varieties in complexion, form, and habits, which distinguish from each other the several races of men. Our curiosity on this subject ceases to be awakened when we have become accustomed to satisfy ourselves respecting it with some hypothesis, whether adequate or insufficient to explain the phenomenon; but, if a person previously unaware of the existence of such diversities, could suddenly be made a spectator of the various appearances which the tribes of men display in different regions of the earth, it cannot be doubted that he would experience emotions of wonder and surprise. To enter into a full consideration of this interesting subject is not within the province of this work. It will, however, be necessary to make a few observations upon it, so far as to demonstrate that the whole family of Man is identically of the same species. Those who desire to enter more largely into this study, may refer to Prichard's "Researches into the Physical History of Mankind," or to Dr. Lawrence's well known "Lectures," in which the able authors have maintained, with the greatest extent of research, and fully proved, a unity of species in all the human races.

Notwithstanding the great diversity which is found to exist the extent of mental acquirements, as well as of the physiological peculiarities, and physical qualities, characterizing, the inhabitants of various portions of the world, there can be little doubt that this diversity is more attributable to external or adventitious causes, to the circumstances in which they live, to their particular habits, their progress in the culture of arts and sciences, and their advancement in civilization and refinement, and to a variety of physical and moral agencies and local circumstances, rather than to any singularity or variation in their original natural organization and endowment. To the operation of all these causes, may be added, the surprising effects of education when almost universally applied, which are sufficiently obvious wherever its influence extends.

Page 8

That climate should also exert a powerful influence on Man may be very reasonably supposed; it has an analogous influence on the other tribes of animated beings. The animal kingdom presents us with numerous striking instances of diversity in the texture and colour of their coverings, occurring, undoubtedly, in the same species. Sheep are particularly marked by the great difference of their fleece, in different latitudes. In Africa, and very warm countries, a coarse rough hair is substituted in the place of its wool, which, in other situations, is soft and delicate. The dog loses its coat entirely in Africa, and has a smooth soft skin. The wool of the sheep is thicker and longer in the winter and in hilly northern situations, than in the summer and on warm plains. Climate, coupled with food, appear to be the great modifying agents, in the production of these and many other varieties in the animal world; but no attempt has been made to assign a separate origin in their case. The white colour, in the northern regions, of many animals, which possess other colours in more temperate latitudes, as the bear, the fox, the hare, beasts of burden, the falcon, crow, jackdaw, chaffinch, &c., seems to arise entirely from climate. This opinion is strengthened by the analogy of those animals which change their colour, in the same country, in the winter season, to white or grey, as the ermine and weasel, hare, squirrel, reindeer, white game, snow bunting, &c. The common bear is differently coloured in different regions.

With regard to the physiological distinctions of Man, there is no point of difference between the several races, which has not been found to arise, in at least an equal degree, among other animals as mere varieties, from the usual causes of degeneration, &c. What differences are there in the figure and proportion of parts in the various breeds of horses; in the Arabian, the Barb, and the German! How striking the contrast between the long-legged cattle of the Cape of Good Hope and the short-legged

Page 9

of England! The same difference is observed in swine. The cattle have no horns in some breeds of England and Ireland; in Sicily, on the contrary, they have very large ones. A breed of sheep, with an extraordinary number of horns, as three, four, or five, occurs in some northern countries--as, for instance, in Ireland--and is accounted a mere variety. The Cretan breed of the same animals has long, large, and twisted horns. We may also point out the broad-tailed sheep of the Cape, in which the tail grows so large that it is placed on a board, supported by wheels, for the convenience of the animal. "Let us compare," says Buffon, "our pitiful sheep with the mouflon, from which they derived their origin. The mouflon is a large animal; he is fleet as a stag, armed with horns and thick hoofs, covered with coarse hair, and dreads neither the inclemency of the sky nor the voracity of the wolf. He not only escapes from his enemies by the swiftness of his course, scaling with truly wonderful leaps, the most frightful precipices; but he resists them by the strength of his body and the solidity of the arms with which his head and feet are fortified. How different from our sheep, which subsist with difficulty in flocks, who are unable to defend themselves by their numbers, who cannot endure the cold of our winters without shelter, and who would all perish if man withdrew his protection! So completely are the frame and capabilities of this animal degraded by his association with us, that it is no longer able to subsist in a wild state, if turned loose, as the goat, pig, and cattle are. In the warm climates of Asia and Africa, the mouflon, who is the common parent of all the races of this species, appears to be less degenerated than in any other region. Though reduced to a domesticated state, he has preserved his stature and his hair; but the size of his horns is diminished. Of all the domesticated sheep, those of Senegal and India are the largest, and their nature has suffered least degradation. The sheep of Barbary, Egypt, Arabia, Persia, Tartary, &c.,

Page 10

have undergone greater changes. In relation to Man, they are improved in some articles, and vitiated in others; but with regard to nature, improvement and degeneration are the same thing; for they both imply an alteration of original constitution. Their coarse hair is changed into fine wool; their tail, loaded with a mass of fat, and sometimes reaching the weight of forty pounds, has acquired a magnitude so incommodious, that the animals trail it with pain. While swollen with superfluous matter, and adorned with a beautiful fleece, their strength, agility, magnitude, and arms are diminished. These long-tailed sheep are half the size only of the mouflon. They can neither fly from danger, nor resist the enemy. To preserve and multiply the species they require the constant care and support of Man. The degeneration of the original species is still greater in our climates. Of all the qualities of the mouflon, our ewes and rams have retained nothing but a small portion of vivacity, which yields to the crook of the shepherd. Timidity, weakness, resignation, and stupidity, are the only melancholy remains of their degraded nature."*

The pig-kind afford an instructive example, because