Richard Allen and Absalom Jones,

by the Rev. George F. Bragg,

In honor of the Centennial of the African Methodist Episcopal Church,

Which Occurs in the Year 1916:

Electronic Edition.

Bragg, George F. (George Freeman), 1863-1940

Text transcribed by Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by Elizabeth S. Wright

Text encoded by Apex Data Services, Inc. and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2003

ca. 65K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2003.

Source Description:

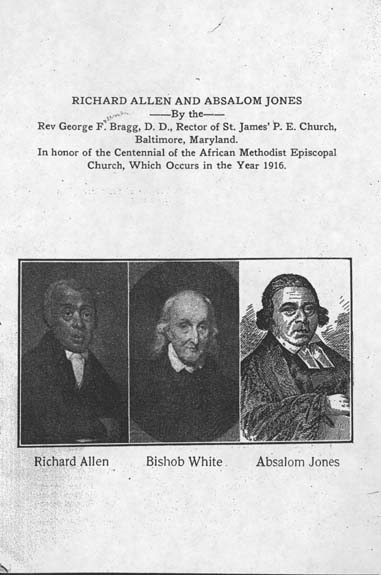

(title page) Richard Allen and Absalom Jones by the Rev. George F. Bragg, D. D., Rector of St. James' P. E. Church, Baltimore, Maryland. In honor of the Centennial of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Which Occurs in the Year 1916.

(cover) Richard Allen, and Absalom Jones

(caption title) Richard Allen and Absalom Jones

Bragg, George F. (George Freeman), 1863-1940

[18] p.

[Baltimore]

[Church Advocate Press]

[1915]

Call number 287.8 B73R (Perry Castañeda Library, University of Texas at Austin)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Jones, Absalom, 1746-1818.

- African Americans -- Religion.

- African American clergy -- Biography.

- United States -- Church history.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- Clergy -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Religious life.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- History.

- Allen, Richard, 1760-1831.

- Clergy -- United States -- Biography.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- Anniversaries, etc.

- St. Thomas' Church (Philadelphia, Pa.) -- History.

Revision History:

- 2004-06-15,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2003-10-07,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Title Page Image]

Richard Allen, Bishop White, Absalom Jones

RICHARD ALLEN AND ABSALOM JONES

--By the--

Rev George F. Bragg, D. D., Rector of St. James' P. E. Church,

Baltimore, Maryland.

In honor of the Centennial of the African Methodist Episcopal

Church, Which Occurs in the Year 1916.

Page 4

RICHARD ALLEN AND ABSALOM JONES.

In the city of Philadelphia, on the 12th of April, 1787, the "Free African Society" was organized. Absalom Jones and Richard Allen were the "overseers" of this new organization. The people of African descent who composed it had been, until recently, worshipers in St. George's Methodist Church. Some unpleasantness had taken place in connection with religious services, and being ejected from the church, they had met together for the purpose of organizing a society among themselves looking to their own general welfare.

The preamble to the articles of association, adopted by this little band of black people, reads as follows:

"Whereas, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, two men of the African race who, for their religious life and conversation have obtained a good report among men, these persons, from a love to the people of their complexion whom they beheld with sorrow, because of their irreligious and uncivilized state, often communed together on this painful and important subject in order to form some kind of religious society, but there being too few to be found under the like concern, and those who were, differed in their religious sentiments, with these circumstances they labored for some time, till it was proposed, after a serious communication of sentiments, that a society should be formed, without regard to religious tenets, provided, the persons lived an orderly and sober life, in order to support one another in sickness, and for the benefit of their widows and fatherless children."

One of the articles of this association provided, "that no drunkard or disorderly person be admitted as a member, and if any should prove disorderly after having been received, the said disorderly person shall be disjointed from us if there be not an amendment."

The society met regularly, from time to time, attending to its business. Its records of moral achievement are intensely interesting. But there seemed to be a drift in the society which was not altogether pleasing to Richard Allen. He seemed to have discontinued his attendance upon the meetings of the society, and in June, 1789, Allen was "accordingly disunited until he shall come to a sense of his conduct, and request to be admitted a member according to our discipline."

For some time there had been a steady tendency of the society towards the formation of an undenominational "church." Accordingly, on the 7th of July, 1791, the following minute was adopted:

"At a special meeting of the Free African Society, convened by direction of the standing committee, a plan of church government, and articles of faith and practice, suited to the establishment of a religious society being read, the Society concluded to unite therewith, and also with an address to the friends of liberty and religion in Philadelphia, and to appoint Absalom Jones to prepare said address."

"Nov. 3, 1792. At a meeting of the Elders and Deacons of the African Church, the members of the Free African Society being convened together, the question was asked the members, separately, whether they design

Page 5

to continue in the church, or whether they prefer to withdraw the money they placed in the Society."

About nine of the members present desired a return of what they had placed in the society. All who desired, were permitted to withdraw, having their money refunded.

The African Church, for it was no longer the "Free African Society," vigorously prosecuted the work of collecting funds, and the erection of the church. The church was finally completed, and formally opened for divine service on the 17th of July, 1794.

It was still the "African Church," with its "Elders and Deacons." On the 12th of August, the next month following, the authorities of the church met and formally gave over themselves to the Episcopal faith. From the document that day submitted, by the Trustees and Founders, the following is taken:

"* * * Whereas, for all the above purposes, it is needful that we enter into, and forthwith establish some orderly, Christian-like government and order of former usage in the Church of Christ; and, being desirous to avoid all appearance of evil, by self-conceitedness, or an intent to promote or establish any new human device among us.

Now be it known to all the world, and in all ages thereof, that we, the founders and trustees of said house, did on Tuesday, the 12th day of August, in the year of Our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and ninety four, RESOLVE AND DECREE,

"To resign and conform ourselves to the Protestant Episcopal Church of North America, and we dedicate ourselves to God, imploring his holy protection; and our house to the memory of St. Thomas, the Apostle, to be henceforward known and called by the name and title of St. Thomas African Episcopal Church of Philadelphia; to be governed by us, and our successors for ever, as follows. Given under our hands this twelfth day of August, 1794."

The Constitution adopted by the church at that time is, historically, most interesting. We give only the "preamble" and sections 1 and 6 of that instrument:

"Preamble--Whereas, we the Founders and Trustees of the African Church of Philadelphia, did by our unanimous consent, at a general meeting held for the purpose, on Tuesday the 12th day of August, 1794, decree, and consent, to commit all the ecclesiastical affairs of our church to the government of the Protestant Episcopal Church of North America, and to establish her creeds and articles of faith among us, as the governing system of our church for ever; and that the following rules shall be the binding constitution of our church forever.

"First--All of our ecclesiastical affairs are committed to the rule and authority of the Protestant Episcopal Church, to be by the Bishop and other officers of said Church and their successors, regulated as occasion may require: Provided always, that the general doctrines, and principles of worship of said church, shall continue as now professed in the same, and understood to be the rule or government of the same. And provided further, that we and our successors shall always retain within ourselves the power of choosing our minister, duly qualified to officiate according to the established rules and discipline of said Church.

"Sixth--We ordain and decree, that none among us, but men of color, who are Africans, or the descendants of the African race, can elect, or

Page 6

be elected into any office among us, save that of a minister or assistant minister; and that no minister shall have a vote at our elections."

The Council of Advice and Standing Committee of the Pennsylvania Diocese, met in the Bishop's house, on September 9, 1794, and accepted the action above noted of St. Thomas' Church, and adopted the following:

"Resolved and declared therefore that as soon as the Trustees or Deputies, of the said congregation, being duly authorized, shall sign the Act of Association of the said Church in this state, they shall be entitled to ALL the privileges of the other congregations of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Agreed, that Dr. Samuel Magaw and Dr. Robert Blackwell, be a committee to meet the Trustees or Deputies of the African Church, and see them ratify the Act of Association.

"On Sunday, October 12, 1794, our being received into the fellowship and communion of the Protestant Episcopal Church of Philadelphia, was most cordially and fully announced from the pulpit by the Rev. Robert Blackwell."

Thus far, all is well. Thus far, everything was lovely. The Constitution provided that only descendants of the African race could hold any office among them, save that of minister or assistant minister. If any explanation of this provision is necessary, it is briefly this. The experience of a few years past in connection with St. George's Church, had thoroughly impressed upon them the wisdom of such a provision. Exception was made to minister and assistant minister, for at that time it was "white" minister or no minister. At that time, there had never been an ordination of a colored man to the ministry. And this explains another provision which some times have been generally misunderstood. When it says, "no minister shall have a vote at our elections" it, necessarily, had reference exclusively to "white" ministers, as, evidently, there was not the least intention of the framers of that constitution, that such section, in years to come, should be used to bar any minister, who was a descendant of the African race from voting in such elections, or acting as the president of the vestry.

The action of the Episcopal Church, in Pennsylvania, up to this time, in connection with the African Church of St. Thomas' was exceedingly generous, and in advance of any similar white ecclessiatical organization with respect to the people of African descent. But, when we reach the next step we are brought face to face with the one thing, more than all others, responsible for the failure of the Church in more largely reaching, and influencing for good, the colored race.

In May, 1849 (the Rev. William Douglass being rector), the rector and vestry of St. Thomas' Church sent a petition to the Diocesan Convention requesting the repeal of the regulation which prevented that congregation from being represented in the diocesan convention. An extract from the request of the vestry of St. Thomas', reads, in part, as follows:

"Your petitioners further represent that they are fully convinced of the superior adaptedness of our Church to the wants of the people represented

Page 7

by them, and that its having failed to command a more universal acceptance among them, is owing, more than anything else, to the anomalous and undignified position we occupy, furnishing as it does, ground of no little discontent within, and of much deriding from without. We therefore pray your honorable body to repeal the eighth regulation which prohibits the aforesaid church from being represented in the convention."

The matter came up at the next convention. The committee appointed to consider it brought in two reports.

The late Rev. Henry E. Montgomery and Prof. G. Emlen Hare, in their "minority" report, sustaining the contention of St. Thomas' Church, most admirably state the situation, and we shall use their words in presenting it:

"It appears, therefore, most clearly, from these records, that, at this time, September, 1794, St. Thomas' Church was entitled to all the privileges of the other Protestant Episcopal congregations in the Diocese, among which was the right of sending Deputies to the State Convention. The Act of Association 'done in Christ Church,' in this city, the '24th day of May, 1785,' expressly providing that the clergy and congregations duly ratifying the said act, shall be called and known by the name of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Pennsylvania, and that each congregation may send to the Convention a Deputy or Deputies, and that all such clergymen as shall hereafter be settled as the ministers of the congregations ratifying this act, shall have the same privileges, and be subject to the same regulations as the clergy now subscribing the same.

"Thus stood the matter in September, 1794, when, as the undersigned believe St. Thomas' Church was in full fellowship with the Church, and entitled to all the privileges of the other congregations of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese.

"In the convention of the succeeding year (June 2nd, 1795), 'It was moved and seconded, that in the examination for Holy Orders of Absalom Jones, a black man, belonging to the African Church of St. Thomas, in this city, the knowledge of the Latin and Greek languages be dispensed with, agreeably to the Canon.

"Resolved, That the same be granted, provided it is not to be understood to entitle the African Church to send a clergyman or deputies to the Convention, or to interfere with the general government of the Episcopal Church, this condition being made in consideration of their peculiar circumstances at present.'

"* * * But what was the 'peculiar circumstances' to which the restriction, passed in 1795, refers? The words 'at present' ought, in charity, to be strictly limited. The Reverend Absalom Jones, the first minister of St. Thomas Church, though very deficient in literary qualifications for the ministry, was a 'man of good report and godly conversation.' He was held in great reverence and esteem by the colored people of our city. Zealous for the prosperity of the Church, and unwearied in doing good, he was especially beloved in conesquence of his devotion to the sick and dying at the time of the prevalence of that awful scourge, the yellow fever. Administering to the bodily as well as spiritual wants of many poor sufferers, and soothing the last moments of many departing souls among his people, he became greatly endeared to the colored race.

"Hence, when they formed a congregation, in order that they might worship God according to the doctrine and discipline of the Church of their choice, they fixed their hearts upon having their kind friend and helper for their minister. He who had already won his way to their hearts by labors and sacrifices of Christian love that no one can hear of without emotion, must be the shepherd of their souls in Christ Jesus. So that they could succeed in this their darling wish, they were content to submit to inconveniences and to loss; for him their friend and brother,

Page 8

bound so closely to their hearts by the sympathy of past afflictions, they were ready to be placed for the time being in a position of inferiority.

"They were fully sensible that he did not possess the literary qualifications requisite for the ministry, but they knew and loved his self-sacrificing spirit, and consistently religious life. When, therefore, the great difficulty in the way of his ordination was removed, by the dispensing vote of the convention, the condition on which, in this case, the dispensation depended was agreed to, the congregation of St. Thomas had succeeded in their great desire. In their feebleness, they surrendered to the far stronger power, the right which the Church had already given them, in order that their little flock might be watched and ministered to by a shepherd whom they loved.

"* * * The undersigned submit, that the Eighth Revised Regulation be rescinded on principle. No test of admission should be adopted here which is at variance with the precepts of our Redeemer, and with the practice of the Church in the Apostolic times--and the undersigned would ask whether the said regulation be not inconsistent with both? If it be urged that darkness of the skin is just cause for exclusion, let us look well at such passages as these from the blessed Gospel: 'One is your Master, even Christ; and all ye are brethren.' 'God hath made of one blood all nations of men, for to dwell on all the face of the earth.' And by His own blood, shed once for all men, hath Christ 'redeemed us to God out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation.' There is no color marked out by our Divine Master and Head for exclusion from even the smallest privilege or honor of the Christian Church. On the contrary, it is a part of the glory of the Church, 'that God is no respecter of persons,' but that all are equally the objects of his parental care and His redeeming love."

"The singularity of its long exclusion, and the stamp of inferiority which is thereby put upon it, are well calculated, as the congregation respectfully set forth in their petition 'to furnish ground of no little discontent within, and of constant deriding from without. Hence they are hindered from greater progress as a congregation, and a subject of vexation and reproach is constantly kept before them.

"It may well be asked if it be consistent with the declaration of the great Apostle to the Gentiles, 'if meat makes my brother to offend, I will eat no flesh while the world standeth, lest I make my brother to offend' thus to wound the feelings and to interfere with the peace and prosperity of a company of brethren. They cannot be expected to reconcile the inconsistency of their pastor being fit to preach the word of God, and to administer His Holy Sacraments, and yet incapable of having any part in the councils of the Church. Can we reasonably look for their advancement and improvement in knowledge and virtue, while we continue to give grounds for attacks upon their position, and thus help to lessen their self-respect. It seems, also, to the undersigned, well worthy of consideration, whether the repeal of the Eighth Revised Regulation would not tend to produce peace in our own Convention?

"It is believed that many of the members of this body are conscientiously opposed to it. It is an offense to them, and they would rejoice to see it rescinded. While it remains on the statute book, it will tend to provoke agitation and dispute, not only on account of its exclusive nature, but also from its remarkable singularity."

Even with this able pleading of its case, St. Thomas' did not win, at this time, but the parish never ceased to "knock," until finally, in 1862, it gained the victory.

Absalom Jones was ordained deacon on August 6, 1795. In 1804, Bishop White reported him as having been advanced to the Priesthood.

Page 9

A SKETCH OF THE REV. MR. JONES.

The Rev. William Douglass says: "The Rev. Absalom Jones, after having been actively and faithfully engaged in the service of the Church for the space of twenty-two years, was released from his anxious toils, and arduous labors, by the welcome messenger --Death--'gathered unto' his 'fathers in the communion of the Catholic Church; in the confidence of a certain faith; in favor with God, and in perfect charity with the world.' He was born a slave; his young ideas, therefore, were never taught how to shoot forth their rays of intellectual light and beauty. He had arrived at manhood before he was initiated into the first branches of a common school education. He became somewhat proficient in these, by dint of self-application, during intervals from his secular labors. By industry, frugality and economy, previous to his entering the ministry, he had accumulated some means which he invested in real estate. He was the owner of several neat dwellings, the value of which we have not ascertained. A day school was taught by him while he pursued a course of preparation for the ministry, and also for some time after he entered upon its duties and responsibilities. When he took charge of the Church he was in the forty-ninth year of his age."

Bishop White, in speaking to the Convention, 1818, of his death, said: "I do not record the event without a tender recollection of his eminent virtues, and of his pastoral fidelity."

Richard Allen.

Some times it is made to appear that the little "rumpus" in connection with St. George's Methodist Church, Philadelphia, wherein Absalom Jones, and other colored worshippers, were ejected from the building, was the immediate occasion of the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. As a matter of fact, the African Methodist Episcopal Church was not established until more than twenty-five years after the above mentioned incident. The outcome of the incident was the formation of the "Free African Society," and the "Free African Society," later, issued into the "African Church," with its "Elders and Deacons," and still later, the "African Church" changed itself into St. Thomas' African Episcopal Church, with the very man, Absalom Jones, who had been pulled from off his knees, in the white Methodist Church, as its first pastor. Discovering the general trend of sentiment in the Free African Society, towards the Episcopal faith, Richard Allen, who had been associated with Jones in the leadership of the Society, withdrew from the organization. Some time after the completion of the "African Church," Richard Allen inaugurated "Bethel" Church. This new enterprise of Richard Allen was united with the same white Methodist organization responsible for the "rumpus" issuing in the formation of the Free African Society. In such association continued Richard Allen and his followers, vexed, harrassed, and embarrassed, for more than a quarter of a century. Finally, in 1816, about sixteen persons of the African race, consisting of representatives from Philadelphia, Wilmington, Del, Baltimore, and one or two other smaller places, got together, in the city of Philadelphia, and organized the African Methodist Episcopal denomination, electing Richard Allen the first Bishop of the new organization. At this

Page 10

time St. Thomas's Church had been in successful operation for about twenty-five years. Its pastor had been ordained to the priesthood twelve years before. And, almost since the very beginning of the Church itself, a day school for African children had been conducted. In 1795 St. Thomas' Church reported more than four hundred and fifty members. Thus, it is a fact that the Episcopal Church welcomed the African race, received its church in full communion, with all the privileges of the other Protestant Episcopal Churches.

Despite all this, Richard Allen, starting twenty-five years later, in weakness, planted a racial connection which was destined, in numbers, and material growth, to completely overshadow, not only St. Thomas' Church, but also the colored membership of the Methodist Episcopal Church. It was not at all strange that the Church of Allen should have had such a wonderful and remarkable growth, in the face of the superior advantages afforded by St. Thomas' Church.

Richard Allen and Absalom Jones remained intimate and affectionate friends until separated by death. Allen could have occupied the place filled by Jones, but he deliberately chose to the contrary. He conscientiously believed that the Methodist system was best suited to the needs of the African race. In the first place, Methodism had addressed itself to the feelings and emotions of the people, and had thereby gotten to itself quite a following from the ordinary whites. If the lowly whites looked upon Methodism as peculiarly adapted to them, still more was it likely that the black people, the lowliest of the lowly, should so much the more look with special favor upon this same kind of religion.

The general ignorance prevailing among the great body of people of the African race was a natural bar to any very great numerical progress of St. Thomas' Church. Added to this, from within the Episcopal Church, was a handicap equally as oppressive. It was the spirit of "caste," while willing to give local self-government to the people of the African race, still objected to receiving them as men and brethren, in the councils of the Church.

The wonder is, not that St. Thomas' Church failed to more largely impress the African people, with respect to increase in numerical strength, but that it maintained leadership during all those dark years of the past, and yielded an indirect influence in racial affairs, for good, in the community, entirely out of proportion to its numerical strength.

As for Richard Allen, the time will come, when all Christian men, whether white or black, who love the Lord Jesus, will recognize in him one of the greatest philanthropists of his times. He bore with his white Methodist friends until patience ceased to be a virtue; and, then, like Abraham, he started out not knowing whither. When Absalom Jones died, the A. M. E.

Page 11

Church was not quite two years old. At the Conference held in the year of 1818, the very year of Jones' death, an inventory was taken. The whole connection numbered only about seven thousand communicants, and about six thousand of these were in the three cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston (S. C.). Allen was a man of some means himself, and he gave not only himself, but his means towards the upbuilding of the organization of which he was the head. So illiterate were the preachers, not to speak of the laity, that that very year, Allen's 14-year-old son acted as secretary of the Conference. In the light of its origin, and all of the attending circumstances, when one looks around today and notes what it is, and what it has achieved on behalf of a poor and suffering race, he would be less than human if he failed to see in it all the spiritual and moral pre-eminence of Richard Allen.

The year 1816 witnessed the organization of the American Colonization Society. The troubles of the "free colored people" were already great and oppressive. The fact of this new organization was calculated to increase and render more painful their anxieties. They were truly as sheep without a Shepherd. The object of this newly-formed society was to remove them from the United States. Poor, ignorant, and without the facilities of communication with one another, and scattered over the North, the birth of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, that very same year, with Richard Allen as its Bishop, seemed almost, as it were, the direct intervention of Heaven on their behalf. The African Church of Allen was in reality a sort of racial clearing house. It had to do not only with "religion," but with everything which had to do with the people of African descent. That was its real mission. The extremity of the need brought it to birth. The few other African churches, at that time in America connected with white religious bodies, were just as race loving, and were working just as earnestly for the common end as Allen and his followers. But, in the very nature of affairs, the organization which was exclusively racial, could, at that time, perform and accomplish what was absolutely impossible to any other. When Hezekiah Grice, of Baltimore, conceived the idea of holding the "first" convention in the States of "free colored persons" in 1830, he instinctively turned to Bishop Allen with his idea, and Peter Williams, and others, in New York, likewise communicated to Bishop Allen their approval of the "idea." Thus, on September 15, 1830, the first convention of its kind which ever assembled in this country, was held in the city of Philadelphia, and Richard Allen was unanimously elected to preside over the same. Richard Allen richly deserves a place by the side of such illustrious characters as John Wesley, Wilberforce and Clarkson. He was pre-eminently a philanthropist. Not simply a lover of black men, but of white men as well. If his

Page 12

character illustrates any one thing, it thoroughly illustrates his love for humanity. Born a slave in the city of Philadelphia, February 14, 1760, he was soon carried to Delaware, where he worked in the field. It was in Delaware that he became acquainted with Absalom Jones, several years his senior. Through the preaching of the "Methodists" he was "converted." And conversion, as illustrated by his subsequent career, meant a new life. He testified and witnessed for the Master among the slaves. His testimony before his "master" was so great and prevailing, that he finally got his freedom. Religious as he was, he would never neglect or hurry over his work in order to go to "meeting." He demonstrated by his interest in his "master's" affairs, and persuading the other slaves, to such conduct, that he was really born of God. He had scarcely moved to Philadelphia to live before he found himself, and Absalom Jones, deeply absorbed in trying to improve the general condition of his people. And, during all this period, he was both industrious and economical. It is worthy of special note that Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, the acknowledged leaders of the race, in those times, were not only of great moral elevation, but were men of means. And it is not at all surprising that God should call such men to leadership of their brethren. They were examples in themselves of the possibilities of the race. When Richard Allen died, he was said to have left an estate valued at between thirty and forty thousand dollars. This he acquired with his own hands. The Church never gave him, but he gave the Church. He gave it his character, his energy, and every faculty he possessed. But he did not stop there. He used his own money to promote the interest and extend the borders of the Church largely of his own creation. It is said that $80 represent all the salary he received from the Church. In fact, upon one occasion when the Philadelphia church was sold he bought it in at an outlay of $10,000.

In his will he bequeathed to the Church arrearages on salary due him.

While greatly esteeming the white Episcopalians, of Philadelphia, who had evinced their kindly interest in the African Church, and race, and while in love and charity with his colored brethren of the Episcopal Church, nevertheless, he was a "Methodist," and could be nothing else. The genuineness of this conviction is thoroughly attested by what he suffered and endured at the hands of his white Methodist brethren. He thought that he could secure peace, and still remain in connection with the Methodist Episcopal Church, by having a separate building. So he established himself on the corner of Lombard and Sixth Sts., in his little "Bethel." Here he labored, and suffered, enduring all kinds of hardships at the hands of his white Methodist brethren. For well-nigh a quarter of a

Page 13

century, with law-suits, vexations, and humiliations of nearly every charactetr, he tried, if it were possible, to get along in communion with his white brethren. At last the stern necessity came, and because there was no other remedy, together with Daniel Coker and Stephen Hill, of Baltimore, and Richard Williams, Henry Harden, Clayton Durham, Jacob Tapscio, James Champion, Peter Spencer, Jacob March, William Anderson, Edward Jackson, Reuben Cuff, Edward Williams, Nicholas Gilliard and Thomas Webster, they got together in a "room," in the City of Philadelphia, in the memorable month of April, 1816, and "Resolved, That the people of Philadelphia, Baltimore and all other places who should unite with them, shall become one body under the name and style of the African Methodist Episcopal Church."

And, thus, in the name of God, they set out not knowing whither they went. It would seem almost like inspiration that those unlearned men of the African race, scarcely out of the house of bondage, should, in that eventful hour, aspire so nobly and heroically, that the people of the African race who should unite with them "should become one body." But, thus it was. Whatever the African Methodist Church is today, and whatever it shall be, its progress, much or little, can only rightly be estimated from the depths from which it issued, with the guiding hand of a black fellow sufferers, raised up out of the dust, and from among the most lowly of his brethren.

Episcopalians and Methodists, of the African race, have a joint and inseparable interest both in Absalom Jones and Richard Allen. It was the same stock which produced them both. Upon the same mission did they both go forth. One, from within, to bear witness to the "Fatherland of God and the Brotherhood of all Men;" and the other, from without, by leading out the internal resources of the same African race, to add fresh and original evidence to the truth of God's Fatherhood, and the Brotherhood of Mankind. In all the united labors of these two men, whether in the yellow fever scourge, or the work of moral reform, or patriotic endeavor, their silent testimony as they moved up and down among their brethren in black, was, "Let us love one another, for he that loveth is born of God." And if this spirit animates and rules the hearts of the present followers of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, we know not how, but yet we believe that in the distant future, the resolve "shall become one body," shall be fulfilled in a larger and dearer sense, that so, the millions of black men now in heathen darkness shall receive the Lamp of Salvation, as a result of the Unity for which the Savior prayed, and which the Church of Allen, at its very birth, seemed to see in the great distance.

Presently, our hearts shall thrill with the getting together of the African race, in response to the command from Heaven.

Page 14

"Rise crowned with light, imperial Salem rise,

Exalt thy towering head and lift thine eyes,

See heaven its sparkling portals wide display,

And break upon thee in a flood of day.

"See a long race thy spacious courts adorn,

See future sons, and daughters, yet unborn,

In crowding ranks on every side arise,

Demanding life, impatient for the skies."

An Estimate a Half Century Ago.

"The African Methodist Episcopal Church is one of the denominations of the United States. It has its own organization, its own bishops, its conferences, its organ or magazine, and these entirely interse--absolutely disconnected with all the white denominations of America. This religious body is spread out in hamlet, village, town and city, all through the Eastern, Northern, Western and partly the Southern States. But the point I desire to direct your attention to is the fact that they have built and now own some 300 church edifices, mostly brick; and in the large cities such as New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, they are large, imposing, capacious, and will seat some two or three thousand people. The free black people of the United States built these churches; the funds were gathered from their small and large congregations; and in some cases they have been known to collect, that is, in Philadelphia and Baltimore, at one collection, over $1,000. The aggregate value of their property cannot be less than $5,000,000.--

The Late Rev. Dr. Alexander Crummell, in 1860.

The Late Bishop Paret, and the A. M. E. Church.

The following was published in the May, 1897, issue of the "Spirit of Missions," the official Missionary magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church:

"Some two years ago *the General Conference of the body known as the African Methodist Episcopal Church was holding its triennial session in the city of Baltimore.

* It was not the General Conference in session, but the annual meeting of their House of Bishops.--Editor.

Although I wanted much to learn what their organization and their work were, important duties of my own made it impossible for me to be present at their sessions: but I sent a note to their presiding officer, Bishop Turner, asking an opportunity to become acquainted, and he named a time when their Bishops would call upon me. They came to my house, seven in number, and we had a very pleasant and profitable interview of some two hours' duration.

"I was soon convinced that these were strong men--men fitted to be leaders, and really leading strongly and wisely. Some, I am sure, were thoroughly educated, whether all were I cannot say; but if not, natural qualities and experience had been well used. Their Presiding Bishop, Turner, began the conversation by telling me, that he learned his first Latin and Greek, and his love for the Church, which he had never lost, in the very room where we were sitting, from the lips of Bishop Whittingham, and the whole conversation proved clearly on the part of almost all the seven, a kindly and loving appreciation of our own national branch of the Church, and a readiness for kindly relations with it.

"I cannot give details, because I counted much of what was said on both sides confidential. They talked freely and fully on all points, begging me to ask questions, and when any special point was raised, Bishop Turner immediately referred it to the one whom he thought specially fitted to answer. The extent of their work, their organization, their financial methods, their ordinations, the training and education

Page 15

of their candidates, the powers and duties of their Bishops, their methods of worship, the morality and spiritual character of their people, their educational institutions--all these were explained.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church is a powerful body. It numbers more communicants in the United States than our own National Church, and has many more who have received its ordinations; and it has its missions in Africa, and at other points beyond the national limits. Its organization is strong, wise (humanly speaking), and efficient. The Bishops being few in number (but eleven or twleve, I think, when their number is full), have each a district as large as six or seven of our dioceses, which they are able to administer by the effective help of the presiding elders, and their oversight seems very thorough and strong. As they tell it, they have many preachers and exhorters, unordained and with imperfect qualifications, lay preachers; but they claim to hold a high standard of preparation for their priesthood, and to keep men relentlessly in their diaconate until they are fully qualified. They set forth a Liturgy, nearly following Wesley's Prayer Book, and they are pushing its use in congregations as they find the people fitted for it. Their educational system is remarkable. They keep up not only schools and high schools; but each Episcopal district is expected to have its college or university, and some of them, like the Wilberforce College, in Ohio, are well equipped and effective; and to sustain these, besides one dollar a year which they request from each member for the general expenses of the Church, they require from each, as a duty, one dollar for their educational work. Of course, they do not receive it from all of their six or seven hundred thousand; but they gave me to understand that at least half of them do contribute. And this leads to that wonderful fact that this great organization of Colored People is entirely self-supporting, receiving no money help at all from the whites.

"In comparing their great work and results among the Colored People with ours, so puny, humanly speaking, in comparison, I asked whether they could see any reason for the difference, and their answer was that we were pauperizing those to whom we ministered, while they were building up their Christian self-respect. They asserted that there was no need that we should keep up such continual missionary support, that it was wise and well to use missionary money freely on opening new fields and fresh enterprises, but that every new congregation should be, from the beginning, pushed rapidly into self-support and helping others. They ridiculed the idea that the Negroes, even the poorest, could not give. They had proved the contrary thoroughly.

"I am sure that in this they have touched one of our great defects; but it is easier to see it than to find and apply the remedy. As a result of the interview, I am wishing and praying, more and more, that in some way by God's good providence a path might be opened for closer understanding and kindly co-operation between that strong Christian body and ourselves. Can it ever be?"

WILLIAM PARET,

Bishop of Maryland.

Page 16

An Estimate By a Prominent Baptist Divine.

"As a separate and distinct organization, the African Methodist Episcopal Church is far and away ahead of any other denomination of Negro Christians. It has the largest number of Bishops and other general officers; it has an excellent printing plant with departments in Philadelphia and in Nashville; it publishes its own Sunday School literature, and conducts three church newspapers and one quarterly religious magazine of a high order. Of all the branches of Methodists, it has the largest number of communicants, and of the great men and leaders of the race this church has its full share, if not more than its full share. Every year, by reason of its system, the African Methodist Episcopal Church raises more money for education and missions, for current expenses and for general purposes, than any other similar organization. As a medium for race expression, as a church which has furnished the world with a shining example of the capabilities and possibilities of the race, the African Methodist Church stands in the very fore-front.

"The denomination with which I have the honor to be connected, the Baptist denomination, when we speak of mere numbers, leads all others--in fact there are more Negro Baptists in this country than there are members of all other denominations above named put together, including those that are intimately allied with the white denominations whose names they bear. Yes; we lead in numbers, but I think, and I sometimes say, that we do not lead in anything else."--

Rev. Dr. C. T. Walker, (1914), Augusta, Ga.

"THE AFRICAN CHURCH."

(From The Life of Bishop Allen, Written By Himself.)

"We viewed the forlorn state of our colored brethern, and saw that they were destitute of a place of worship. They were considered as a nuisance.

"A number of us usually sat on seats placed around the wall, and on Sabbath morning we went to church, and the sexton stood at the door and told us to go in the gallery. He told us to go and we would see where to sit. We expected to take the seats over the ones we formerly occupied below, not knowing any better. We took those seats. Meeting had begun, and they were nearly done singing, and just as we got to the seats the Elder said: "Let us Pray." We had not been long upon our knees before I heard considerable scuffling and loud talking. I raised my head up and saw one of the trustees, H-- M--, having hold of the Rev. Absalom Jones, pulling him off his knees, and saying: "You must get up; you must not kneel here." Mr. Jones replied: "Wait until prayer is over." Mr. H-- M-- said: "No, you must get up now, or I will call for aid and force you away." Mr. Jones replied: "Wait until prayer is over, and I will get up and trouble you no more." With that he beckoned to one of the other trustees, Mr. L-- S--, to come to his assistance. He came and went to William White to pull him up. By this time prayer was over, and we all went out of the Church in a body, and they were no more plagued by us in the church. This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, insomuch that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct. But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigor to get a house erected to worship God in. Seeing our forlorn and wretched condition, many of the hearts of our citizens were moved to urge us onward; notwithstanding, we had subscribed largely towards furnishing St. George's Church, in building the gallery and laying new floors; and just as the house was made comfortable, we were turned out from enjoying the comforts of worshipping therein. We then hired a storeroom and held worship by ourselves. Here we were pursued with threats of being disowned and read publicly out of

Page 16a

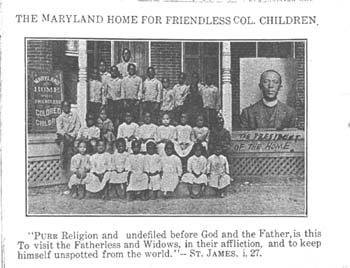

[Inserted card between pages 16 and 17]

THE MARYLAND HOME FOR FRIENDLESS COL. CHILDREN.

"PURE Religion and undefiled before God and the Father, is this To visit the Fatherless and Widows, in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world." -- ST. JAMES, i, 27.

Page 16b

SPECIAL NOTICE.

St. James' First African Church, Baltimore, was, in 1824, initiated by William Levington, the second black man ordained by Bishop White in St. Thomas' Church, Philadelphia. The Maryland Home for Friendless Colored Children, fifteen years ago, was founded by the present rector of St. James' Church, Baltimore. The "first" legacy received by this institution was bequeathed by one of the first pupils of St. James' African Free School (taught by Mr. Levington) who was the late widow of the late African Methodist Bishop Wayman. The proceeds from the sale of this booklet will be given to this orphanage for fatherless and friendless Colored Children. Quantities of the same, of twenty or more copies, may be had of the Author at five cents each.

Page 17

the meeting, if we did contrive to worship in the place we had hired; but we believed the Lord would be our friend. We got subscription papers out to raise money to build the house of the Lord. By this time we had waited on Dr. Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston, and told them of our distressing situation. We considered it a blessing that the Lord had put it into our hearts to wait upon these gentlemen. They pitied our situation and subscribed largely towards the church, and were very friendly towards us, and advised us how to go on. We appointed Mr. Ralston our treasurer. Dr. Rush did much for us in public by his influence. I hope the names of Dr. Benjamin Rush and Mr. Ralston will never be forgotten among us. They were the two first gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed and aided us in building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in. Here was the beginning and rise of the First African Church in America. But the elder of the Methodist church still pursued us. Mr. I-- M-- called upon us and told us if we did not erase our names from the subscription paper, and give up the paper, we would be publicly turned out of meeting. We asked him if we had violated any rules of discipline by so doing. He replied, "I have the charge given me by the Conference, and unless you submit, I will read you publicly out of meeting.' We told him we were willing to abide by the discipline of the Methodist Church, 'And if you will show us where we have violated any law of discipline of the Methodist Church, we will submit, and if there is no rule violated in the discipline, we will proceed on.' He replied, 'We will read you all out.' We told him if he turned us out contrary to the discipline we should seek further redress. We told him we were dragged off our knees in St. George's Church, and treated worse than heathens, and we were determined to seek out for ourselves, the Lord being our helper. He told us that we were not Methodists, and left us. Finding we would go on in raising money to build the church, he called upon us again, and wished to see us altogether. We met him. He told us that he wished us well, and that he was a friend to us and used many arguments to convince us that we were wrong in building a church. We told him that we had no place of worship, and we did not mean to go to St. George's Church any more, as we were treated so scandalously in the presence of all the congregation present, 'and if you deny us your name, you cannot seal up the Scriptures from us and deny us a name in heaven. We believe that heaven is free for all who worship in spirit and in truth.' And he said, 'So you are determined to go on.' We told him, 'Yes, God being our helper.' He replied, 'We will disown you all from the Methodist Connection.'

"We believe that if we put our trust in the Lord he would stand by us. This was a trial that I never had to pass through before. I was confident that the great Head of the Church would support us. My dear Lord was with us. We went out with our subscription paper and met with great success. We had no reason to complain of the liberality of the citizens. The first day the Rev. Absalom Jones and myself went out we collected three hundred and sixty dollars. This was the greatest day's collection that we met with. We appointed a committee to look out for a lot--the Rev. Absalom Jones, William Gray, William Licher and myself. We pitched upon a lot at the corner of Lombard and Sixth Streets. They authorized me to go and agree for it. I did accordingly. The lot belonged to Mr. Frank Wilcox. We entered into articles of agreement for the lot. Afterwards, the committee found a lot on Fifth Street, in a more commodious part of the city, which we bought; and the first lot they threw upon my hands, and wished me to give it up. I told them they had authorized me to agree for the lot, and they were all satisfied with the agreement I had made, and I thought it was hard that they should throw it upon my hands. I told them I would sooner keep it myself than to

Page 18

forfeit the agreement I had made. And so I did. We bore much persecution from many of the Methodist Connection, but we have reason to be thankful to Almighty God, who was our deliverer. The day was appointed to go and dig the cellar. I arose early in the morning and addressed the throne of grace, praying that the Lord would bless our endeavors.

"Having by this time, two or three teams of my own--as I was the first proposer of the African Church--I put the first spade in the ground to dig a cellar for the same. This was the first African Church or meeting-house that was erected in the United States of America. We intended it for the African preaching house or church; but finding that the Elder stationed in the city was such an opposer to our proceedings of erecting a place of worship, though the principal part of the directors of this church belonged to the Methodist Connection, and that he would neither preach for us nor have anything to do with us, we held an election to know what religious denomination we should unite with. At the election it was determined. There were two in favor of the Methodist, the Rev. Absalom Jones and myself, and a large majority in favor of the Church of England. The majority carried. Notwithstanding we had been violently persecuted by the Elder, we were in favor of being attached to the Methodist Connection, for I was confident there was no religious sect or denomination that could suit the capacity of the colored people as well as the Methodist, for the plain and simple Gospel suits best for any people, for the unlearned can understand, and the learned are sure to understand; and the reason that the Methodist is so successful in the awakening and conversion of the colored people is the plain doctrine, and having a good discipline. But in many cases the preachers would act to please their own fancy, without discipline, till some of them became tyrants, and more especially to the colored people. They would turn them out of society, giving them no trial, for the smallest offenses, perhaps only hearsay. They would frequently, in meeting the class, impeach some of the members of whom they had heard an ill report, and turn them out, saying, 'I have heard thus and thus of you, and you are no more a member of society,' without witnesses on either side. This had been frequently done, notwithstanding in the first rise and progress in Delaware State, and elsewhere, the colored people were their greatest support, for there were but few of us free. The slaves would toil in their little patches many a night until midnight to raise their little truck to sell to get something to support them, more than their white masters gave them, and we used often to divide our little support among the white preachers of the Gospel."

"Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that His justice cannot sleep forever; that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events; that it may become probable by supernatural interference. The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.--Thomas Jefferson.

Price 10 Cents a Copy.

CHURCH ADVOCATE PRESS,

BALTIMORE, MD.,

1915.

Return to Menu Page for Richard Allen and Absalom Jones... by George F. Bragg

Return to North American Slave Narratives Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page