Behind the Scenes of the 'Scenic': An Unnatural Road in a Staged Landscape

Hélène Ducros, edited by Neale Stokes

The Blue Ridge Parkway not only provides access to the natural landscape of western North Carolina; it can also be appreciated as a space in which the relationship between nature and culture is carefully structured, managed, and maintained. A short stretch of the Parkway known during construction as "Section 2Y" (Milepost 455.5-461.5) provides a setting to explore the human effort required to create and maintain what is popularly perceived as scenic and natural. From the very beginning, the planning and construction of the Parkway presented the challenge of controlling the physical environment. This challenge, however, did not end with the completion of construction. In fact, the road remains in constant need of management and maintenance — from repairs due to weather or geological events, to the signage which orders and interprets the landscape for visitors.

Waynesville Mountaineer article on the completion of section 2Y

Photograph by NCC,

Courtesy Waynesville Mountaineer

Section 2Y crosses two counties, Haywood and Jackson. During the section's construction years (1941-42) the Waynesville Mountaineer, Haywood County's largest newspaper, highlighted the formidable construction and engineering feats carried out during Parkway construction. Not only were a great number of men working on Section 2Y — as many as 105 men at one time — heavy equipment was also needed to shift earth and tunnel through solid rock. Wagon drills, Koerhing trucks, and air compressors, "some of the heaviest equipment to have been used on the Parkway," The Mountaineer noted, were brought to the area.

The Colorado-based Lowdermilk Brothers were contracted to grade the road and drill three tunnels (Lickstone, Bunches Bald, and Big Witch -- a total of 1055 feet of tunnel). While the construction of section 2Y's 5.95 miles through mountainous terrain was challenging, the tunnels proved especially difficult. The Mountaineer noted that during one tunnel's construction, "loose dirt and rock caused several breaks in the wall;" the tunneling was later described to be "as dangerous work as has been done in this area."

At the completion of their work on section 2Y, the Lowdermilk Brothers were commended by their insurance company for both their rapid work and their success in avoiding accident and injury. This effort to conquer the natural environment--at the risk of human lives, at great expense, and with such a show of machine force--is one aspect of the tension between nature and culture on the Parkway.

While the Lowdermilk Brothers overcame considerable natural obstacles in their work on Section 2Y, the struggle with nature did not end when they powered down their heavy equipment. During the 1950's, the section suffered from three major landslides and at least one tunnel failure. Geology, weather, and climate undoubtedly played a role in these disasters; but the considerable human intervention in the landscape set the stage.

The Parkway's route through this region was not the first choice of the road's planners. The Eastern Band of Cherokees refused to grant a right-of-way for the Parkway in lower but more productive land along what is now U.S. 19. As a result, it was decided in 1940 that the road follow a ridge-top route, where land was "scenically beautiful and agriculturally useless." [1] This routing decision increased the complexity of engineering and construction, which now required aggressive cuts to achieve a passable grade for the roadway. The Mountaineer reported that "the deepest cut on the road is 108 feet through solid rock," and that "other cuts are as deep as 93 feet through dirt." As mentioned above, the section also required over a thousand feet of tunnel. Such extensive alteration of the landscape increased its vulnerability to natural trigger events; the resulting failures demonstrated a need for continual repairs and modifications along the Parkway.

Parkway Land Use Map, section 2Y

PLUM 2Y-9, United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, 1963.

The "natural landscape" to which the road provides access turns out to be far from pristine. National Park Service Parkway Land Use Maps (PLUMs) reveal that much of what Parkway visitors see was carefully orchestrated. The PLUMs represent detailed and explicit plans for the scenery surrounding the Parkway. Evident in the maps is the high degree of human intervention required to craft the Parkway visitors' aesthetic experience. The maps show planners detailing the number, location, and species of trees surrounding the parkway. They quantify the number and acreage of open vistas, woods, shrub bays, and grass bays. Such planning shows the effort to enhance the natural landscape for the benefit of the park visitor, while not disrupting the perception of the landscape as authentically natural.

Drawing upon well developed ideas of landscape architecture and design, National Park landscapes have, since the beginning of the National Park Service in 1916, made conscious and thoughtful efforts to shape the experience and perceptions of visitors. National Park design in the period of the Parkway's construction was also marked by extensive use of "naturalistic" design principles that employed "rustic style" design features to conceal the extensive manipulation of nature that was required to create a park. In devising a carefully planned sequence of scenes for the traveler to view, Blue Ridge Parkway planners employed techniques of what Ethan Carr calls "wilderness by design." [2]

Parkway signage in storage at submaintenance area

Photograph by Stout,

Courtesy National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway

The amount of planning, selecting, and arranging that had to be done in connection with initial construction was extensive. Yet the designed landscape that was thereby produced is also a dynamic, living thing, and keeping up a consistent appearance has required consistent intervention. Behind the scenic overlooks, a whole apparatus of maintenance is in place.

This work includes maintenance of the Parkway road, but also encompasses the maintenance and continuous orchestration of the landscape itself. Submaintenance areas are fenced off and tucked out of sight. Also concealed are administrative offices, law enforcement stations, and staff residences. The parkway visitor rarely glimpses the complex mechanism by which the 'scenic' is constructed and preserved.

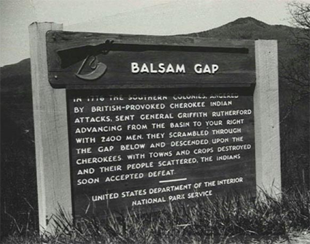

Reminiscent of a theater's scene shop, this photo of a sign in storage hints at a secondary meaning of the word 'scenic' — that which refers to the theatrical and the staged. Far from a pristine and virgin wilderness, the Parkway landscape is indeed a carefully staged interpretation of the relationship between people and nature. Signs along the Parkway obviously function to direct and provide information, but they also carry meaning in their form and design. The Balsam Gap sign below is of a style that appears often along the Parkway, with rough-hewn natural materials and a handmade appearance consistent with the early twentieth-century "rustic era" of park architecture and landscape design. [3]

Parkway's signs mediate between the Parkway's landscape and its visitors. They tell people where to go, how to behave, what to look at, and even how to interpret what they see.

1. US Department of the Interior, Kappler's Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties, Volume VI, 1979.

2. David Louter, Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington's National Parks (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 60-63.; Ethan Carr, Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service. (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

3. Carr, Ethan. Wilderness by Design : Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, c1998.

Related Reading

Allen, William Cicero, Centennial of Haywood County and its County Seat, Waynesville, NC, 1908

Carr, Ethan. Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

Louter, David. Windshield Wilderness: Cars, Roads, and Nature in Washington's National Parks, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Panorama of Progress: Jackson County Centennial, Sylva, NC, Jackson County Centennial Celebration Committee, 1951

Sax, Joseph, Mountains Without Handrails: Reflections on the National Parks, University of Michigan Press, 1980.

Urry, John, The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies, Sage Publications, 1980.

Whisnant, Anne, Mitchell, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History, UNC Press, 2006.

William, Max R., The History of Jackson County, Sylva, N.C. : Jackson County Historical Association, 1987