Hampton and its Students. By Two of its Teachers, Mrs. M. F. Armstrong and Helen W. Ludlow.

With Fifty Cabin and Plantation Songs, Arranged by Thomas P. Fenner:

Electronic Edition.

Armstrong, M. F. (Mary Frances), d.1903,

Helen W. Ludlow (Helen Wilhelmina), d. 1924 and Thomas P. Fenner

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Andrew Leiter

Images scanned by

Andrew Leiter

Text encoded by

Sarah Reuning and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 450K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Hampton and its Students. By Two of its Teachers, Mrs. M. F. Armstrong and Helen W. Ludlow. With Fifty Cabin and Plantation Songs, Arranged by Thomas P. Fenner.

(cover) Hampton and its Students

(spine) Hampton and its Students. With the Slave Songs

Mrs. M. F. Armstrong, Helen W. Ludlow, and Thomas P. Fenner

255 p., ill.

New York

G. P. Putnam's Sons

1874

Call Number LC2851 .H32 A7 (Davis Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

When the verses of a song were broken over several pages in the original text, the verses were transcribed and inserted after the images of the music.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- Education (Higher) -- Virginia -- Hampton.

- African Americans -- Music.

- Education -- Virginia -- Hampton -- History.

- Folk music -- Southern States.

- Hampton (Va.) -- History.

- Hampton Institute -- History.

- Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (Va.) -- History.

- Slavery -- Southern States -- Songs and music.

- Spirituals (Songs) -- Southern States.

Revision History:

- 2001-08-31,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-06-20,

Jill Kuhn, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-06-15,

Sarah Reuning

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-05-23,

Andrew Leiter

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

Page 1

Young Women's Department, with Industrial and Dining Rooms.

[Virginia Hall stands just in rear of the above long wooden, building, which will eventually be removed.]

Teacher's Residence.

Hampton Creek.

Barn and Store-House.

Young Men's Department, with Assembly and Recitation Rooms.

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute.

[BEFORE THE ERECTION OF VIRGINIA HALL.]

Page 2

HAMPTON

AND ITS STUDENTS.

BY

TWO OF ITS TEACHERS,

MRS. M. F. ARMSTRONG

AND

HELEN W. LUDLOW.

WITH FIFTY CABIN AND PLANTATION SONGS,

ARRANGED BY

THOMAS P. FENNER,

IN CHARGE OF MUSICAL DEPARTMENT AT HAMPTON.

"I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher,

I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher,

I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher;

Den my little soul's gwine to shine, shine,

Oh! den my little soul's gwine to shine along."

"I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher,

I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher,

I'm gwine to climb up higher and higher;

Den my little soul's gwine to shine, shine,

Oh! den my little soul's gwine to shine along."

Old Slave Song.

NEW-YORK:

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS.

1874

Page 3

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

HELEN W. LUDLOW,

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Page 4

PREFACE.

THE desire to know more about Hampton and its students, on the part of the many friends of this Institution, has been one reason for publishing this little book. To them, and to the many other friends of the freedmen and of all the great interests of humanity who, we hope, will be made Hampton's friends by reading it, the authors wish to say that while the impressions it gives of the school and the life in and around it are in every sense their own, for which they are therefore alone responsible, the historical and statistical information contained in these pages is official, and may be relied upon as accurate.

For all of its illustrations, except the first and the last three, the book is indebted to the courtesy of Messrs. Harper Bros., who have kindly allowed the use of their wood-cuts.

M. F. A.

H. W. L.

Page 5

CONTENTS.

- THE SCHOOL AND ITS STORY . . . . . M. F. Armstrong. 7

- A TEACHER'S WITNESS . . . . . M. F. Armstrong. 36

- THE BUTLER SCHOOL . . . . . M. F. Armstrong. 67

- INTERIOR VIEWS OF THE SCHOOL AND THE CABIN. Helen W. Ludlow . . . . . 71

- What is the Privileged Color? . . . . . 75

- A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing . . . . . 78

- How Aunt Sally Hugged the Old Flag . . . . . 81

- The Woman Question Again . . . . . 85

- The Richness of English . . . . . 91

- The Sunny Side of Slavery . . . . . 95

- Father Parker's Story . . . . . 101

- "Want to feel right about it" . . . . . 105

- A Case of Incomplete Sanctification . . . . . 109

- Just where to put dem . . . . . 115

- Hunger and Thirst after Knowledge . . . . . 121

- THE HAMPTON STUDENTS IN THE NORTH--SINGING AND BUILDING. Helen W. Ludlow. . . . . 127

- VIRGINIA HALL . . . . . Helen W. Ludlow.151

APPENDIX:

- Appeal . . . . . 159

- The Southern Workman . . . . . 161

- Speech of the Hon. William H. Ruffner . . . . . 161

- Letters from Public School Officers and others . . . . . 163

- Financial History of the Institute . . . . . 165

- Extract from the Catalogue of 1873-74 . . . . . 167

- Report of Prof. R. D. Hitchcock and others . . . . . 170

- CABIN AND PLANTATION SONGS . . . . . Thomas P. Fenner. 171

Page 6

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute . . . . . Frontispiece.

- Virginia Hall . . . . . 8

- Walls of St. John's Church . . . . . 12

- Teachers' Home and Girls' Quarters . . . . . 26

- Chapel and Farm Manager's Home . . . . . 41

- Lion and John Solomon . . . . . 42

- Printing-Office . . . . . 43

- Girls' Industrial Room . . . . . 45

- Assembly-Room . . . . . 50

- Reading-Room . . . . . 54

- Winter Quarters . . . . . 60

- Ball Club . . . . . 64

- Butler School-House . . . . . 66

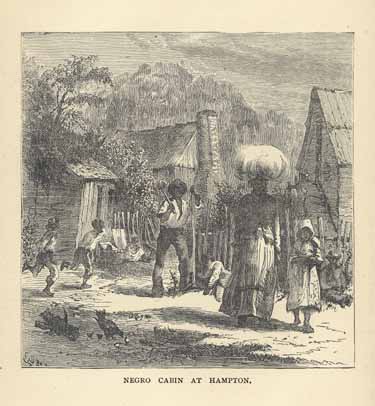

- Negro Cabin at Hampton . . . . . 72

- Virginia Hall--New Building . . . . . 152

- Virginia Hall--Second-floor Plan . . . . . 154

- Virginia Hall--Interior of Girls' Room . . . . . 156

Page 7

THE SCHOOL AND ITS STORY.

By M. F. A.

AMONG all the States of the Union, not one has a history more interesting than Virginia, for her annals are full of strangely poetic incident, from the world-famous idyl of Pocahontas to the tragic stories still fresh in our own memories; and from the fertile seaboard to the rich mountain valleys of her western border, there is scarcely a field or village that has not its tale to tell. More than one great name, "familiar in our mouths as household words," belongs in the catalogue of Virginia's children; and although to-day her greatness is a thing of the past and the future, yet that future promises such certainty as is more than guaranteed by her natural advantages and the brave and willing temper of her people.

In the history of this State, there arose, long years ago, an unnatural relation between two races, which furnished a problem, dealt with by statesmen, philanthropists, and fanatics, and finally solved by God himself, in his own time, and his own way; and it is with an outgrowth of that problem and its solution that this little book has to do.

The introduction of negroes into the country as slaves was made at a time when only a few minds, here and there, had any true conception of the rights of individuals, or could put a fair interpretation upon that higher law which makes us our brothers' keepers; and the virgin soil and relaxing climate of

Page 8

THE HAMPTON INSTITUTE--THE NEW BUILDING, VIRGINIA HALL.

the South made slavery so temptingly easy and profitable as to insure its continuance until a Power stronger than humanity interfered to bring it to an end. In no part of the United States can the history of negro slavery, from its origin to its extinction, be more clearly traced than in Virginia; and as that State was chosen as the scene of bitterest struggle, so it seems likely to attain the earliest and highest development, for within its borders are now being fairly tested the possibilities of, the African race, and the results to them and the whites of the new relations of freedom. It is not too much to say that throughout the history of slavery in Virginia, there runs a strain of poetic justice which is absolutely dramatic, robbing facts of their dryness and interweaving the prosaic details of life with the elements of tragedy. Nowhere has there been greater prosperity, nowhere has there been greater suffering, and many a page might be filled with the record of the changes which a century has wrought, of the old things that have passed away, and the new hopes that are blossoming for the future; and in writing this brief story of an experiment which is just nowPage 9

being tried upon Virginian soil, there will be an earnest attempt to offer such testimony of the capacity of a hitherto enslaved race, and of the intelligent and generous action of their whilom owners, as shall not be altogether valueless.

This experiment of negro education is too serious a matter to be treated otherwise than with the severest honesty; it is not to be wrought out in the white heat of fanaticism, or the glow of a superficial sentiment, but must rather be tested by patient, practical trial on the largest possible scale; and such trial can at present be made only under specially favorable circumstances. There must be a suitable climate, a need and an ability to pay for skilled labor, and a fairly unprejudiced and intelligent white population, while, of course, the willingness of the blacks themselves to assist in the work of their own enlightenment must, to a certain extent, be taken for granted. Such a combination of circumstances exists in a marked degree in Virginia, and in that State, past events seem, in a curious fashion, to have paved the way for the present endeavor. Not but that what may be found true of the blacks in Virginia will hold good in all parts of our Southern country, but merely that in all initial experiments of this nature, involving possibly the life of a whole race, justice demands that the weakness and ignorance of those whose fate hangs in the balance should, if possible, be compensated for by the offer of especial opportunities.

Therefore, when we ask our readers to go back with us at first into the past of a little Virginian town, we are only asking them to trace by and by for themselves a logical sequence of events whose results promise to-day a glorious success, and whose close relation to each other can scarcely be without interest to any who are taking thought as to the future of the

Page 10

African people on this continent. We have said that there is scarcely a village in Virginia that has not its tale to tell, and truly no romancer need desire richer material than lies ready to his hand in many of the older settlements which still bear the mark of their English origin, and hold in their mouldy parish-registers or upon the moss-grown stones in their neglected graveyards, the names of famous old English houses whose cadets, or even whose heads, came with rash enterprise to meet their death in the wilderness which they dreamed was to yield them instead a fabulous treasure.

Just at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, where one of its numerous tributary creeks opens into the broad harbor of Hampton Roads, stands a little village, scattered along the western shore of the creek, with its half-ruined houses and low, white cabins irregularly clustered upon the level green meadows down to the very water's edge. The back country through which the creek wanders for the few miles of its course, and the shore itself, are flat and monotonous, except for the brilliant coloring and golden, semi-tropical sunshine which for eight months in the year redeem the landscape from the latter charge. But the changeful beauty of the shore, even when at its climax in the fresh spring months, can bear no comparison with the eternal beauty of the sea, which, stretching far on either hand, offers by day and night, in calm and storm, new glories and beautiful, strange surprises of color and sound and motion. When the fury of an Atlantic storm drives vessel after vessel into the secure anchorage of the Roads, until a whole fleet is gathered under the guns of Old Point Comfort; or when, on some bright, breezy morning, scores of white-winged oyster-boats put out from every safe nook of the shore, dotting the sparkling blue of the bay like snowy birds; or, better

Page 11

still, when the fading crimson glow of sunset makes the shore shadowy and indistinct, and the little returning flotilla floats tranquilly homeward to the slow dip of oars and the weird, rich singing of the negro boatmen--then one gazes and listens, to confess at last that such scenes are hard to rival, and that this unfamiliar bit of Virginia coast need not fear the verdict of critics with whom still lingers the remembrance of Mediterranean skies or distant tropic seas.

By this broad, shining sea-path, there came, more than two hundred years ago, the daring little band of Englishmen who settled the town of Hampton, and made it their head-quarters in the colonization of the neighboring country. Their story is too well known to every child in America to need recapitulation here. Their hopes and their disappointments, their struggles and sufferings, their defeats, and final victory over the obstacles that opposed their determination to possess, in their Queen's name, the beautiful fertile land they had discovered-- all these are a part of the nation's history not easily to be forgotten. In Hampton itself still stands the quaint little church of St. John, built between 1660 and 1667, and the records of the court, which date as far back as 1635, prove that even before that time a church had been built; while the old, deserted graveyard has many a grave whose hollow holds the dust of English hearts broken or wearied out by unaccustomed hardship. Here and there may still be found vestiges of these earliest occupants of the soil; but from its first settlement, the town of Hampton has passed through such vicissitude as does not often fall to the lot of an obscure village; for the fortunes of war have been uniformly against it, and it has seen more wars than one. In 1812, the town was sacked and left desolate, its geographical position exposing it to especial dangers, while it was unable to

WALLS OF ST. JOHN'S CHURCH.

Page 12

defend itself, and was not of sufficient importance to receive efficient protection.

Years before this time, however, the curse which was the cause of the blighted prosperity, not of one town only, but of the whole South, had fallen, and when the first cargo of slaves was landed within a few miles of Hampton, it was as if men's eyes were thereafter blinded to the light of God's truth, for from that hapless day, each year but added to the incubus, until relief could only come through fire and sword. Viewed in the

Page 13

light of later events, this landing of the first slaves at Hampton ranks as one of the strange coincidences of fate; for here upon the spot where they tasted first the bitterness of slavery, they also first attained to the privileges of freemen, the famous order which made them "contraband of war," and thereby virtually gave them their freedom, having been issued by General Benjamin F. Butler, from the camp at Fortress Monroe, in May, 1861.

The year of 1861 opened with threats of trouble near at hand, and before the spring had fairly set in, our civil war began, the country in the neighborhood of Fortress Monroe becoming almost immediately the scene of bitter contest; for the importance of that post as a Centre of operations was second to none other on the Atlantic seaboard. The creek upon which Hampton stands was for a while the boundary-line between the two armies--the Union lines remaining intrenched upon its eastern shore during the early part of the war, while the combating forces swayed back and forth as fortune favored one or the other. The town and the long bridge across the creek were burned, and the few houses of the richer residents which escaped the general destruction were made the head-quarters of Union or Confederate officers, as might be, until the lawless hands of successive possessors had obliterated all traces of former luxury. Before the war, Hampton and Old Point Comfort were favorite watering-places with the better class of Virginians, and summer after summer had seen the rambling, airy houses filled with Southern aristocracy; so that the havoc of war wrought a quick and startling change from the gayety of one season to the terror of the next.

But as the months went by, a greater change than all drew near; and when in the early summer of 1861, troops of blacks

Page 14

came pouring in from the interior of the State and the northern counties of North-Carolina, then, indeed, the real meaning of the war and its inevitable end became apparent, and the question was no longer, "What is to be done with the slaves?" but instead, "What is to be done with the freedmen?"

Newbern, North-Carolina, and Hampton, Virginia, were the two cities of refuge to which they fled, their lives in their hands, as the Israelites of old fled from the avengers of blood. Fortress Monroe and its guns offered tangible protection, and the spirit of the officers in command promised a surer protection still; so that in little squads, in families, singly, or by whole plantations, the negroes flocked within the Northern lines, until the whole area of ground protected by the Union encampments was crowded with their little hurriedly-built cabins of rudely-split logs. A remnant of these still remains in a suburb of Hampton, numbering about five hundred inhabitants, and known by the significant name of Slabtown, and another called more euphoniously Sugar Hill--on some principle of lucus a non lucendo, it must be, as it is situated on a dead level, and certainly has no appearance of offering much literal or figurative sweetening to the lives of its inhabitants.

How these people lived was and still is a mystery, for the rations issued them from the army and hospital establishment were necessarily insufficient, and those at the North who would gladly have welcomed the new-comers with practical assistance were already overburdened with the paramount claims of army work. However, all through that long first summer of the war, we find occasional evidence that these new-born children of freedom were not altogether forgotten; and in October of the same year, we know that organized work was begun among them.

Page 15

This work was initiated by the officers of the American Missionary Association, who, in August, 1861, sent down as missionary to the freedmen, the Rev. C. L. Lockwood, his way having been opened for him by an official correspondence and interviews with the Assistant Secretary of War and Generals Butler and Wool, all of whom heartily approved of the enterprise and offered him cordial coöperation. He found the "contrabands" quartered in deserted houses, in cabins and tents, destitute and desolate, but in the main willing to help themselves as far as possible, and of at least average intelligence and honesty. There was, of course, little regular employment to offer them, and they subsisted upon government rations, increased by the little they could earn in one way and another. Mr. Lockwood's first work was the establishment of Sunday-schools and church societies, and his own words show the spirit in which the assistance he was able to give was offered and received. He says, in one of his first letters to the American Missionary Association, "I shall mingle largely with my religious instruction the inculcation of industrious habits, order, and good conduct in every respect. I tell them that they are a spectacle before God and man, and that if they would further the cause of liberty, it behooves them to be impressed with their own responsibility. I am happy to find that they realize this to a great extent already."

This was certainly encouraging, and he goes on to report that he finds little intemperance, and a hunger for books among those who can read, which is most gratifying. He appeals at once for primers, and for two or three female teachers to open week-day schools; and recommends that, in view of the imperativeness of the need, the subject should be brought before the public through the daily press and by means of public

Page 16

meetings. At the same time, he describes the opening of the first Sunday-school in the deserted mansion of ex-President Tyler, in Hampton, and, from his personal observation, declares that many of the colored people are kept away from the schools by want of clothing, a want which he looks to the North to supply. A little later in the year, he writes that, on November 17th, the first day-school was opened with twenty scholars and a colored teacher, Mrs. Peake, who, before the war, being free herself, had privately instructed many of her people who were still enslaved, although such work was not without its dangers.

From this time, schools were established as rapidly as suitable teachers could be found and proper books provided; but it must be noted that these teachers were working almost without compensation, their sole motive being a desire for the elevation of the race. As a proof of the quick awakening of the ex-slaves to a sense of the duties of freedom, Mr. Lockwood mentions that marriages were becoming very frequent, and that although the fugitives lived in constant fear of being remanded to slavery, they did not remit their efforts to obtain education and to raise themselves from the degradation of their past.

In December, 1861, at the annual meeting of the American Missionary Association, it was resolved that "the new field of missionary labor in Virginia should be faithfully cultivated, and that the colored brethren there were fully entitled to the advantages of compensated labor;" which latter clause was a much-needed acknowledgment, for in the same month we find it stated that government, in return for the rations supplied to the freedmen around Fortress Monroe, claimed the labor of all who were able to work, giving them a nominal payment, the

Page 17

greater part of which was retained by the quartermasters for the use of the women, children, and infirm. The honesty and wisdom with which this provision was apportioned depended, of course, upon the character of the quartermasters and their interest in the people; and there is do doubt that even when the administration was thoroughly just, the supply was entirely inadequate to the need. In accordance with the above resolution, the American Missionary Association increased the number of their colored employees, and, in January, 1862, sent down a second reënforcement of missionaries and teachers-- the reports of the progress of the negroes and their eagerness for knowledge continuing remarkably favorable, while the devotion of a few was worthy of a more public acknowledgment than it has ever received; as, for example, Mrs. Peake, who died in April, 1862, having literally laid down her life for her people, for whom she labored beyond her strength until death lifted her self-imposed burden.

During all these months, the attention of the Northern public had been gradually attracted toward the condition of the freedmen at various points throughout the South, and, on the 20th of February, 1862, a great meeting was held in the Cooper Institute, New-York, at which many prominent men were present, and a committee appointed who organized themselves as the "National Freedmen's Relief Association," and announced their desire "to work, with the coöperation of the Federal Government, for the relief and improvement of the freedmen of the colored race; to teach them civilization and Christianity; to imbue them with notions of order, industry, economy, and self-reliance; and to elevate them in the scale of humanity by inspiring them with self-respect." This meeting gave incontrovertible evidence of the rapidity with which sympathy

Page 18

for the freedmen had grown up in the North; but at the same time this sympathy was as yet, necessarily, of a very general character, and, indeed, it was not then possible to enter into details, for the great fact of the permanent emancipation of the slaves was not yet fully established, and innumerable difficulties beset those who undertook any systematized effort for their relief. Complaints had been made in regard to the treatment of those at Fortress Monroe, and General Wool had appointed a committee to examine into their condition, moral and physical, which commission, after a faithful discharge of their duty, reported on most points favorably--making, however, some suggestions as to future action, the principal of which was the recommendation that the government should appoint some responsible civil agent to the charge of the improvement of the freedmen. Captain C. B. Wilder, of Boston, was appointed superintendent of their affairs, and rendered efficient service in their behalf.

Mr. Lockwood still held his position as missionary to Hampton, and in July of this year wrote that the building of small tenements was going on rapidly, gardens were being cultivated, while a church and school-house were finished and occupied; and one of the officers of the American Missionary Association reported, on his return from a tour of inspection, that the general evidences of improvement were most satisfactory. Undoubtedly, the quick and generous reply of the North to the demand made upon their beneficence had much to do with the safe transition of the blacks from slavery to freedom; but it must be remembered that opinion in the North was still divided, and that more was due to the patient, determined spirit of the freedmen themselves than to any other cause, A noteworthy exhibition of this spirit occurred shortly after the decision of

Page 19

the officers of the "Freedmen's Bureau," that no more rations

were to be issued to the blacks about Fortress Monroe, at a

time when a large number of them had no visible means of

support except such as government furnished. The distribution

of rations ceased abruptly upon a certain day, October

1st, 1866,*

*See Appendix, Note i.

and the expectation of the officers stationed at

Hampton was that there would ensue general and probably

serious disturbance in the crowded quarters of the colored

people, who must necessarily feel the deprivation very acutely.

On the contrary, the report of these officers is, that the order

was carried out without producing the smallest expression of

dissatisfaction, and the usual tranquillity was maintained. The

two thousand freedmen who had been fed by government

for years, and were living in the depths of poverty answered

almost at once the sudden and severe draught upon their

resources, and proved themselves possessors of unsuspected

strength.

Ignorant as these people were, they knew that they were free, and in no way did they mean to trifle with their new-found blessing. They had a curiously quick appreciation of the fact that freedom meant little to them unless they knew how to use it, and they discerned for themselves that their primary need was education. After the President's proclamation, published in October, 1862, the demand for schools steadily increased, and as the opportunities for their safe establishment and support increased also, there began an amelioration of the condition of the freedmen, which promised to be permanent because based on a sure foundation. The physical destitution was so great that no charity, however broad, could

Page 20

do more, than afford superficial relief, and it soon became evident that, on every account, the best help for these people was that which soonest taught them to help themselves. Untrained as they were, even in respect to the simplest facts of life, their education had at the outset to be, of necessity, of the most elementary character, and such primary schools as could with comparative ease be supplied with both teachers and books amply sufficed, and for the first two or three years seemed to the blacks like the gates of heaven. As the number of fugitives near Hampton grew from month to month, and the prospect was that for many of them the settlement there would become a permanent home, these primary schools increased in number and capacity, one of them alone receiving within three months more than eight hundred scholars, while night-schools and Sunday-schools took in many who for various reasons could not attend during the usual day-school hours.

The Society of Friends at the North had, early in the war, shown great interest in the freedmen, had sent several teachers to Hampton and the vicinity, and was at this time occupying one of the deserted houses as an Orphan Asylum. These teachers worked in hearty coöperation with the teachers of the American Missionary Association, and the little band struggled bravely with the gigantic undertaking, for the work at this point, where there were not less than 1600 pupils, was growing so rapidly that failure here was especially to be dreaded.

But no teachers of another race could do for the freed people what was waiting to be done by men and women of their own blood. In 1866, the American Missionary Association determined upon the opening of a normal school, and in January, 1867, there appeared in the American Missionary Magazine an

Page 21

article by General S. C. Armstrong, earnestly and ably setting forth the need of normal schools for colored people, wherein they could be trained as teachers, and fitted to take up the work of civilizing their expectant brethren; and this article was followed later in the year by reports from various well-qualified employees of the American Missionary Association as to the feasibility of this scheme. They were unanimous in their approval, and strongly urged the necessity of immediate action, recommending the establishment of normal or training schools as soon as adequate funds could be procured.

As is evident from the foregoing sketch of the growth of the work at Hampton, every thing pointed to that place as of primary importance; for, here was collected one of the largest settlements of fugitives (the population being of greater relative density than at any other point on the Atlantic coast), here was a central and healthy situation, and here was protection and a close connection with the sympathies of the Northern public. Furthermore--and herein the thought of God seems too clear for us to dare to speak of it as "chance"--the chief official of the Freedmen's Bureau at Hampton was at this time General S. C. Armstrong, late Colonel of the Eighth Regiment U. S. Colored Troops and Brigadier-General by Brevet, whose interest in the blacks was earnest and practical, and whose peculiar preparation for the work before him has had so much to do with the results of that work, that it can not be passed over unnoticed.

General Armstrong is the son of the Rev. Richard Armstrong, D.D., who for nearly forty years was missionary to the Sandwich Islands. It may be interesting, in connection with his son's work in Virginia, to know that Dr. Armstrong received his doctorate from Washington College, Lexington,

Page 22

Va., with whose President, Rev. Dr. Junkin, he was an intimate friend at Carlisle College, Pa.

During sixteen years of his long life as missionary, Dr. Armstrong was Minister of Public Instruction of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and in that position largely influenced the policy of the government in respect to the school system of the Islands. He succeeded in establishing the higher schools upon a manual-labor basis, and these schools have been and still are remarkably satisfactory, both pecuniarily and in the character and efficiency of their graduates. Dr. Armstrong's life as a public man was one of incessant labor, and in the sphere of usefulness which he may be said to have created, his son was trained until his twenty-first year, when, after having served actively in the Department of Public Instruction at Honolulu for one year, he was sent into the stimulating atmosphere of a New-England college, to complete his education, at Williamstown, Mass. Graduating from Williams College in the summer of 1862, he at once entered the army as captain in a New-York regiment, shortly afterward received a commission in the U. S. Colored Troops, and as colonel of a colored regiment, gained an experience of the negro in a military capacity, which at the close of the war was supplemented by a term of service in the Freedmen's Bureau, where he became thoroughly familiar with the civil needs of the newly-made citizens.

Trained by this rare combination of events, General Armstrong, placed in a position of power at Hampton, seized at once the salient points of the situation, and found himself, from very force of habit, in quick sympathy with the people for whom he was called upon to act. Thenceforward, the key-note of the work of which we write was found in the fact that its chief brought from Hawaii to Virginia an idea, worked out by American

Page 23

brains in the heart of the Pacific, adequate to meet the demands of a race similar in its dawn of civilization to the people among whom this idea had first been successfully tested.

General Armstrong saw that the need of the freedmen, now that their escape from slavery had become a certainty, was a training which should as swiftly as possible redeem their past and fit them for the demands that a near future was to make upon them. They needed not only the teaching of books, but the far broader teaching of a free and yet disciplined life, and the surest way to convince them of their own capacity for the duties imposed upon them by freedom was to show them members of their own race trained to self-respect, industry, and real practical virtue. Teachers of their own race must be had, young men and women, who could go out among them, and, as the heads of primary schools, could control and lead the children, while, by the influence of their orderly, intelligent lives, they could at the same time substantially affect the moral and physical condition of the parents. Normal schools upon the broadest plan were the thing required; and as the American Missionary Association, who, by right of their earnest labor, were in possession of the field at Hampton, were favorably inclined to such an experiment, General Armstrong resolved, with their coöperation and at their request, to devote himself to the work of founding a manual-labor school for colored people, from which should go forth not only school-teachers, but farm teachers, home-teachers, teachers of practical Christianity, bearing with them to their work at least some faint reflection of the spirit of Christ himself. What could be more natural, more beautiful than the growth of such a school within the lines of Camp Hamilton, close to the spot sullied by the footsteps of the first slaves, on the very ground where the first

Page 24

freedmen's school was opened, and where, when the Monitor and the Merrimac met yonder in the blue water of the "Roads," a crowd of dusky figures was gathered in piteous, imploring prayer that victory might not be unto the foe, whose success meant the old terror, the awful darkness, of human bondage.

Here then should rise, God willing, the walls of such a building as America had never seen, a building whose corner-stone should be the freedom of Christianity, and from whose gates should go out, year after year, men and women fitted for righteous labor among a people whose past is a blot upon the national honor, staining the escutcheons of both North and South, and to whom North and South, alike owe a debt to be repaid only by wise and liberal care for many a day to come.

So, in the midst of suffering, in the midst of dangers and uncertainties, with no sure promise of support, the school began its life, and inaugurated its work in April, 1868, being incorporated by the General Assembly of Virginia, in June, 1870, as the "Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute," with the following Board of Trustees: President, George Whipple, New-York; Vice-Presidents, R. W. Hughes, Abingdon, Va.; Alexander Hyde, Lee, Mass.; Secretary, S. C. Armstrong, Hampton, Va.; Financial Secretary, Thomas K. Fessenden, Farmington, Ct.; Treasurer, J. F. B. Marshall, Boston, Mass.; O. O. Howard, Washington, D. C.; M. E. Strieby, Newark, N. J.; James A. Garfield, Hiram, Ohio; E. P. Smith, Washington, D. C.; John F. Lewis, Port Republic, Va.; B. G. Northrop, New-Haven, Ct.; Samuel Holmes, Montclair, N. J.; Anthony M. Kimber, Philadelphia, Pa.; Edgar Ketchum, New-York City; E. M. Cravath, Brooklyn, N. Y.; H. C. Percy, Norfolk, Va.; who now hold and control the entire property of the Institute, and to whose wisdom is due the adoption of the

Page 25

carefully elaborated system which experience has proved to be so successful.

Little by little, the building grew; money and helping hands

came from the North; a hundred acres of good farm-land gave

opportunity for that practical education in agriculture so sadly

needed throughout the South; and although the struggle was

unceasing, the spirit of those on whom the burden fell never

for a moment flagged, and the work went steadily on. One

by one, friends were made who pledged themselves that

"Hampton" should not fail; and the wisdom and experience of

more than one co-laborer were placed at General Armstrong's

disposal. With the hearty generosity characteristic of him,

General O. O. Howard, both as head of the Freedmen's Bureau

and as a private individual, gave good help again and again to

the school which was to do a work after his own heart, and

from the date of its opening to the present day, he has proved

an unfailing friend and benefactor.*

*See Appendix, Note 2.

As the plan of the

school became more generally understood, students flocked in,

not from Virginia alone, but from many States of the South,

and showed an appreciation of the opportunity offered them

greater than the most hopeful of the laborers among them had

dared to expect. The corps of teachers was necessarily enlarged,

and a "Home" furnished for them in one of the

houses purchased with the farm, while a long line of deserted

barracks and a second building, formerly used as a grist-mill,

were taken for girls' dormitories--these, with the necessary

barns and workshops, all standing in convenient neighborhood

to each other, close down upon the shore, completing the present

list of school-buildings.

Page 26

TEACHER'S HOME AND GIRL'S QUARTERS.

The history of the school from the time of its legal organization until today is the history of a brave struggle against opposing circumstances, which has been made thus far successful by the determined spirit of students and teachers, the steady liberality of Northern friends, and the generosity of Virginia. In recalling the list of those who have fed the growth of the school with full and cheerful bounty, it is almost impossible to avoid the mention of special names and instances, and yet in any such mention it is inevitable that much must be left unsaid and the story of many a gracious deed remain untold. There is perhaps no feature of the history of Hampton more striking and more valuable as a proof of the power of unity of purpose than the fact that the school is, as it claims to be, truly unsectarian, and that while founded by the American Missionary Association, and therefore strictly orthodox in its origin and evangelical in its teaching, it ranks among its supporters and warm friends, Quakers, Unitarians, societies and men of every shade of belief.

Page 27

The gift which gave Hampton its first impetus came in the spring of 1867, when the Hon. Josiah King, one of the executors of the "Avery Fund," of Pittsburg, Pa., visited Hampton, and decided to expend, through the Association, $10,000 of that legacy in assisting to purchase the "Wood Farm" or "Little Scotland," a tract of land on the east side of the creek, known during the war as Camp Hamilton, in which, at one time, as many as fifteen thousand sick and wounded Union soldiers have been cared for. This property consisted of 125 acres of excellent land, besides two outlying lots of small value, containing 40 acres, with some $12,000 worth of available buildings, and the total cost was $19,000, of which the American Missionary Association paid $9000, thus holding the property until the appointment of the Board of Trustees, whose names have already been given, to whom the property and control of the school were transferred in 1872.

As a natural result of military occupancy, the farm was at this time entirely out of condition, and both buildings and soil required an immediate and comparatively large outlay. The Freedmen's Bureau made an appropriation of about $2000 to aid with the buildings, and just as this was exhausted, and the position most critical, Mrs. Stephen Griggs, of New-York, made a timely gift of $6000, increasing it afterward to $10,000, which put the institution on a firm foundation. From time to time, General Howard, as chief of the Freedmen's Bureau, granted additional funds for building and other purposes, amounting to upward of $50,000, and contributions of from $50 to $500 dropped in from various sources, increasing as the school grew, and furnishing so sure a supply, that, although the treasury was at times absolutely empty, and the coming of the next dollar an entire uncertainty, yet, in obedience to some unknown

Page 28

law of supply and demand, the next dollar never failed to come and save the school from a bankruptcy which was more than once threatened. Thus, when the present Academic Hall had been completed, at a cost of $48,000, and $44,500 was all that the most strenuous efforts had been able to secure, a generous lady of Boston canceled the debt. And now again, when the recent panic in the money market had caused the income of resources for the building of Virginia Hall to cease entirely, two Boston friends guaranteed the funds for completing the walls and putting on the roof--a gift of about $10,000. Experiences like this can not fail to strengthen our faith that this is God's work, and will go on in the future as it has in the past.

In 1872, the school received its first aid from Virginia, which was bestowed on it in its character as an agricultural college, and acknowledged as follows by the Board of Trustees at a meeting held in Hampton, June 12th, 1872:

"Resolved 1. That the trustees of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute accept the trust reposed in them by the General Assembly of Virginia, in the act approved March 19th, 1872, entitled, 'An Act to appropriate the income arising from the proceeds of the land scrip accruing to Virginia under act of Congress of July 2d, 1862, and the acts amendatory thereof, on the terms and conditions therein set forth.'

"Resolved, 2. That, in view of this appropriation, the trustees hereby stipulate to establish at once a department in which thorough instruction shall be given, by carefully selected professors, in the following branches, namely, Practical Farming and Principles of Farming; Practical Mechanics and Principles of Mechanics; Chemistry, with special reference to Agriculture; Mechanical Drawing and Book-keeping; Military Tactics.

"Resolved, 3. That the trustees request leave of the curators

Page 29

to invest, at an earlyday, not more than one tenth of the principal of the land fund assigned to this institution in additional lands, to be used for farm purposes, and to expend not exceeding five hundred dollars ($500) during the present year in purchasing a chemical laboratory.

"Resolved, 4. That the Principal of this institution be authorized to receive one hundred students from the free colored schools of this State, free of charge, for instruction and use of public buildings, to be selected by him, in such manner as may, be agreed upon between himself and the Board of Education of the State of Virginia."

The appropriation was 100,000 acres of the public land scrip, sold in the market for $95,000, one tenth of which was expended for seventy acres of additional land, and the balance invested in State bonds bearing six per cent interest.

This noble gift is worthy of Virginia's advanced position in the work of development and progress before the South,*

*See Governor Walker's letter, Appendix, Note 5.

a

position to which her Superintendent of Public Instruction, Dr.

Win. H. Ruffner, points with just pride in his last deeply interesting

report to the General Assembly. She is not only at the

head of all the Southern States in the work of education, by her

numerous colleges and universities, by her splendid school systems

of Richmond and Petersburg, and her general and generous

provision for common schools throughout the State, but it is

proven by statistics that "where the white population alone is

concerned, Virginia has a larger proportion of her sons in superior

institutions probably than any State or country in the world."

"What stronger evidence," Dr. Ruffner justly asks, "could be

presented of the love of Virginia for the higher branches of

learning than the fact that it can not be quenched or even

Page 30

partially suppressed by the pinching poverty which now over-spreads the South?" It is evident that, as he told us last summer, at Hampton commencement, "our old State has entered honestly and uncomplainingly upon the work of educating her people, white and colored, with impartiality, and to the extent of her ability, and she intends to keep on with it."

The curators mentioned in the above resolutions are nine in number, five of whom are appointed by the Governor every fourth year, and it is provided that three of these five must be colored men. The State Board of Education, composed of the Governor, Attorney-General, and State Superintendent of Education, together with the President of the Virginia Agricultural Society, are curators ex-officio.

The full Board consists at present of Gilbert C. Walker,*

*By the last election of November, 1873; General James L. Kemper was elected Governor of Virginia, and becomes President, ex-officio, of the Board of Curators.

Governor of Virginia, President of the Board of Education;

James E. Taylor, Attorney General; William H. Ruffner, Superintendent

of Public Instruction; William H. F. Lee, President

Virginia Agricultural Society. (The above named are ex-officio members.)

Appointed for a term of four years: O. M. Dorman, of Norfolk, Va.; Thomas Tabb, of Hampton, Va.; William Thornton, of Hampton, Va.; James H. Holmes, of Richmond, Va.; Cæsar Perkins, of Buckingham C. H., Va.

This body of curators meet the trustees annually for the

transaction of business, the last annual meeting bringing together

a remarkable group of men of two races and opposing

sentiment, who united in complete amity for a work of which

they, one and all, appreciated the importance.+

+See Appendix, Note 8.

Page 31

This spirit of amity, of mutual respect, and good-will which has been constantly developing between the school and its Southern neighbors in the State and the town has been indeed one of the most gratifying and encouraging features in its history, and a most essential element in its success. Abundant evidence of the existence of such a spirit is found in the fact that from many of the best citizens of Hampton, the school has received friendly visits and frequent words of encouragement and good-will. One of her most eminent citizens is a member of the State Board of Curators of the Institute, and as its legal adviser, has rendered valuable and gratuitous service. To one of her leading clergymen, the school is indebted for interesting and instructive lectures, and for words of Christian sympathy and friendly counsel. One of her principal physicians has offered his services gratuitously to the school. More than one merchant of the town has made a liberal discount from his bill against it, and one, in doing so, adds these kind words:

"Please accept this as my humble mite toward the support of your admirable institution. Would that my means were such as to justify a more liberal discount."

All these instances of good-will, and others which could be named, have come from citizens whose fortunes were cast with the South, in the late civil contest, and it is a pleasure to receive such proofs of their appreciation of the real aim and scope of the work. The distrust and occasional disfavor with which the enterprise was first viewed by some of them have gradually given place to confidence and good-will as time has developed its workings and its influence, and there is now between the school and its neighbors generally a mutual feeling of pleasure in each other's prosperity.

Page 32

The growing prosperity of the town of Hampton, since its desolation by the war, is indeed a matter for rejoicing. Romantic as has been the tragic history of its past, it is by no means interesting merely as a ruin, but, on the contrary, is recovering itself with a rapidity that is striking and significant. The "contraband" tide which overwhelmed it in 1861, in ebbing, left a residue behind which makes its population (2500) still nearly three quarters negro, but the condition of the freedmen, then greatly demoralized, has constantly improved. Five years ago, the trustees of the Normal School appropriated a portion of its lands for the erection of model cottages, which were sold to the freedmen at paying prices.

The ambition to become land-owners, encouraged in this and in other ways, has so increased among them, that, as an intelligent white citizen of Hampton recently remarked, "not one of them is satisfied now till he owns a house and lot, and a cow. All the money he can get he saves up to buy them." A striking sign of the improvement in the relations of the freedman with his white neighbors is the fact that one of the principal proprietors of land in Hampton, one of its old residents, has recently been selling off his lots successively to white and colored bidders as they chanced to present themselves.

The army of slab huts which once overran the desolated streets has retreated to an outpost, which it still holds, but is gradually melting away before the advancing forces of civilization.

The town itself is steadily rising from its ashes. It has some fifty stores, a new and well-kept hotel, while the ancient walls of St. John's Church, which have withstood so many of the shocks of time, no longer stand in picturesque ruin, but gather within them every Sunday many of those who worshiped

Page 33

there before the war. The little village is in a generally thriving condition, and bids fair to reëstablish its long-held reputation as an attractive seaside resort, as many of the friends and guests of the Normal School have already found it a pleasant place of retreat from bitter northern storms, with its unsurpassed beauty of situation, and its climate, temperate in the main (though not entirely free from the terrors of the frost), the pleasures of midwinter boating on its land-locked waters, its Christmas roses, and its perennial oysters. It is the centre of historic ground, and is surrounded by places well worth visiting, whose names recall associations of thrilling interest: Yorktown, Newport News, Norfolk, Big Bethel, are all within a radius of twenty miles. Two miles down the creek, at the mouth of Hampton Roads, is Fortress Monroe, interesting both in its historic past and its present busy life as a military post and artillery school, under command of Major-General W. F. Barry. Nearer still is another friendly neighbor of the school, the Chesapeake Military Asylum, as it is popularly called, the Southern branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteers. The large, commanding edifice occupied before the war by one of the principal young ladies' seminaries of Virginia now shelters nearly four hundred invalid veterans, under the kind and able command of Captain Woodfin, U. S. Volunteers, and is a monument of the nation's gratitude, at all times worthy of inspection.

These are some of the attractions of Hampton, but among them the school itself surely ranks first, in view of what it has done and is doing to solve some of the grave problems left to the country by the decisions of the war, the problems of reconstruction for blacks and whites, of the readjustment of disturbed

Page 34

social equilibriums, of what to do with the negro, and what to do for the South.

The influence of a live, active power like this institution should certainly be felt in the circle immediately surrounding it, and may claim some place among the causes of Hampton's growth. Not only by adding somewhat to the business of the place, but by making itself and its objects respected, by giving honor to industry, and working out the visible results of skilled labor and practical education, by manifesting a spirit of helpful sympathy and honest intent to the community around it, it has established a position therein which is cordially acknowledged, and deserves such estimate by the thinking men of the South as was expressed on the last commencement-day by Rev. Dr. Ruffner:

"It would have been easy to establish a school here that would have been hateful to the intelligent people of the State, and been mischievous just in proportion to its success. But this school is worthy of all praise. Its aim has been honest and single. It is just what it seems to be--a purely educational institution, giving satisfaction to all and offense to none."

Such, up to this time, has been the history of the "Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute," and the noteworthy fact stands out, we trust, clearly enough that the school is a growth; no unfinished, one-sided, unstable creation of an individual whim, but a natural, healthy growth. It has not been forced upon the people; it is not a makeshift until something better can be had; it has not been endowed by any one person, to be at the mercy of a changing humor; but, on the contrary, it has met a people's imperative demand, and having met that demand honestly, it bears within itself the reason for its permanent continuance and increase, while the fact that its acres have been

Page 35

bought and its bricks laid with money from a thousand different sources has rooted its claims in a multitude of hearts, and made its future very hopeful.

The system adopted in the first instance by the officers and trustees has been, with some modifications, continued, and has certain peculiarities which entitle it to such a description as can best be given from the personal observation of one who, as a teacher, has obtained a familiar knowledge of its working and its results. The following pages are therefore devoted to an account of the actual condition of the school, giving, also, something of the experience of the troupe of colored singers known as the "Hampton Students," who were sent out in the winter of '72-3, in the hope that the appeal of their music and their faces might enable the Hampton treasury to meet the calls made upon it by the rapidly increasing student-roll. The endeavor has been, in presenting this brief history to the public, to create, if possible, an intelligent and lasting interest in the future of Hampton, and to show that, while its work was at the outset necessarily experimental, the school has already become theoretically and practically a success, needing only a reasonable increase of means in order to take its place as one of the most important institutions of the South.

Page 36

A TEACHER'S WITNESS.

BY M. F. A.

IT is evident that the only test of any system of education which can be of value is the test of practical application, and when the founders of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute were called upon to decide as to the general character of the school they were about to establish, they were keenly alive to the importance of making use of all possible means to insure the success of their unique undertaking, an undertaking which was at that time so far without precedent as to be to many minds simply chimerical.

First of all, therefore, they consulted the needs of those who were destined to become the pupils of the school, and then took careful account of the experience of various experimentalists, a course which resulted in the adoption of a "Manual Labor System," which, by right of the originality of certain of its features, may fairly be known as the "Hampton System." This system, as it stands, is remarkable; because, while it has drawn largely from different sources in our own and other countries, its application to a people scarcely emerged from, slavery made requisite certain peculiarities which are particularly worthy of notice as being a direct result of an unparalleled social revolution.

The slaves, whose emancipation made such a school as Hampton possible, found, as the inevitable effect of their enslavement, their chief misfortune in deficiency of character

Page 37

rather than in ignorance. They were improvident, without self-reliance, and immoral. On the other hand, they possessed the virtues of patience and cheerfulness, a hearty desire for improvement, especially in book knowledge, while in many cases there existed a religious fervor often amounting to a form of superstition, so vivid was, and still is, their belief in all conditions of the supernatural, from God to Satan. Four millions of these slaves were set free with absolutely no preparation for a state of which the novelty alone was sufficient to blind or dazzle their unused faculties, and with scarcely more than nominal restraint or assistance, were left to shift for themselves, in the midst of the ruins of the only social law of which they had any experience.

It can hardly be necessary to allude in other than the briefest terms to the condition of the Southern States directly after the war; and, indeed, there are only two facts which require just here to be dwelt upon--namely, first, that the slaveholders bereft of their slaves were almost as helpless as the slaves, so far as concerned the retrieval of their fortunes; for not only had six generations of slave-owning in a marked manner enfeebled the power of a majority of the dominant race, but the annihilation of property in men left the South in almost universal bankruptcy; second, that enforced labor being no longer to be had, the future of the South depended upon the speedy creation of a class of skilled and willing laborers, and that such laborers were to be found mainly in the vast army of unemployed freed men and women.

No one for whom the question had any interest could fail to see that the best hope of both whites and blacks lay in a wise training of both races for the work that was waiting for them, and the establishment in the South of schools that should afford

Page 38

such training. General Armstrong, stationed as an officer of the Freedmen's Bureau at Hampton, where the work had been already so well begun by the American Missionary Association, saw the importance of locating one of these schools at that point, central as it was to the great negro population of Virginia, North-Carolina, and Maryland, a population numbering more than a million. The seed sown years ago in far-off Pacific islands sprang now into quick fruitage, for a youth passed among a people similar in many respects to the Anglo-African, gave him a peculiar power to grasp the problem of the successful establishment of a normal school for freedmen. The intelligent and liberal support of the American Missionary Association and the Freedman's Bureau enabled him, when appointed Principal of the Hampton Institute, to adopt a manual-labor system, his opinion being that such a system, carefully prepared, would best meet the exigencies of the case. He had seen the successful working of such schools among the semi-civilized natives of the Sandwich Islands, and his own views were strengthened by the testimony of some of the oldest of the pioneer missionaries, one of whom, the Rev. Dwight, Baldwin, D.D., in writing to Hampton, gives briefly the result of their experiments among the Hawaiian people. He says, "The Lahainaluna school has been a great light in the midst of the Hawaiian Islands. For the whole forty years that it has been in operation, it has been a mighty power to aid us in enlightening and Christianizing the Hawaiian race. Without this seminary, how could we have furnished any thing like efficient teachers for a universal system of common schools, a system which has already made almost the entire people of these islands readers of the Bible? Then, also, of all the native preachers and pastors who have been enlisted in this good

Page 39

work, it has been very rare to find one particularly useful who has not been previously trained in this seminary. And throughout the islands, except just about the capital, where foreigners are employed, the execution of the laws depends entirely upon educated Hawaiians. It has always been a manual-labor school. This arose partly from necessity; but a second reason was that all our plans for elevating this people were laid from the beginning to give them not only learning, but also intelligent appreciation of their duties as men and citizens, and to prepare them in every way for a higher civilization. The plan pursued here in this respect is the same, I believe, essentially, as you have pursued at the Hampton Institute. It is the plan dictated by nature and reason, and if you pursue it thoroughly and wisely, it will make your Institute a speedy blessing to all the freedmen of the South."

From such witnesses as these, and from the carefully reported experience of schools in Germany, France, and Great Britain, all possible facts were obtained, and Hampton, in 1868, was inaugurated as a manual-labor school. To the completeness with which it has fulfilled its original design, many witnesses have borne testimony, and that one given by the Rev. George L. Chancy, of Boston, in January, 1870, is especially interesting from its impartiality:

"This school, open alike to men and women of every race, but only attended now by freedmen, sets the rule of education to the whole nation. The State which is kept standing on the threshold of our Union carries in her hands the ideal school. The Northern men and women who went South to teach have learned more than they have taught. Driven by the necessity of their impoverished pupils, they have learned to combine an education of the hand with the education of the

Page 40

mind. It is already written in the proof-sheets of the new history, that Massachusetts learned from Virginia how to keep school."

At the very outset, the trustees were wise enough to reject the theory that the manual labor performed by students must necessarily be made profitable, but based their efforts upon the fact that their system had for its primary object the education of the pupils. They devoted themselves to obtaining for the scholars such advantages as the nature of their past lives made specially desirable; and realizing distinctly that true manhood is the ultimate end of education, of experience, and of life, they grounded their work on the conviction that the best and most practical training is that of the faculties which should guide and direct all the others. They appreciated also the comparative uselessness of educating the men of any race when their mothers and sisters are left untrained, and resolved that the Hampton system should include both sexes under the most favorable possible circumstances.

The school opened in April, 1868, with twenty (20) scholars and two (2) academic teachers, while for the term beginning September, 1873, the catalogue shows us a roll of twelve (12) teachers in the academic department, six (6) teachers in the industrial departments, and two hundred and twenty-six (226) pupils. These figures in themselves represent success, and the reports of the various departments furnish still further proof that the division of labor and study has been satisfactory to teachers and scholars, while the pecuniary result is altogether better than was originally expected. At the opening of the present term, the system may be considered as matured, and the division of the school into academic and industrial departments, each with its separate corps of teachers, under the

Page 41

CHAPEL AND FARM MANAGER'S HOUSE.

control of one principal, has been found to afford the required advantages.The farm of one hundred and ninety (190) acres, which includes seventy-two (72) acres of the "Segar Farm," recently purchased with the avails of the Land Scrip Fund, is managed by an experienced farmer; and for the purpose of interfering as little as possible with recitations, the students are divided into five squads, which are successively assigned one day in each week for labor on the farm. All the boys also work a half or the whole of every Saturday, during the term. Each student has therefore, each week, from a day and a half to two days of labor on the farm, for which he is allowed from five to ten cents an hour, or from seventy-five cents to two dollars a week, according to his ability.

From two to four hired men are steadily employed to take care of teams, drive market-wagon, etc.; but the greater part of the farm-work is done by the young men of the school. Market-gardening is carried on extensively, hundreds of dollars' worth of asparagus, cabbages, white and sweet potatoes, peas,

Page 42

and peaches being annually sold at Fortress Monroe, or shipped to the markets of Baltimore, Philadelphia, New-York, and Boston. Between twenty and thirty gallons of milk are daily supplied to the boarding department of the school or sold in the neighborhood, at an average price of thirty cents per gallon.

LION AND JOHN SOLOMON.

The introduction of blooded stock, a French Canadian stallion, Ayrshire cattle, Chester, pigs, etc., is directly benefiting the farmers of the surrounding country, the appreciation of the value of these importations being shown by the fact that at the Virginia and North-Carolina State Agricultural Fair held in Norfolk, in the autumn of 1872, three first prizes were taken by normal-school stock.

The division of the one hundred and forty-six (146) acres under cultivation during the past year is as follows:

- Corn . . . . . 55 acres.

- Wheat . . . . . 35 acres.

- Barley . . . . . 4 acres.

- Corn-fodder . . . . . 6 acres.

- Peas . . . . . 4 acres.

Page 43 - Early potatoes . . . . . 7 acres.

- Sweet potatoes . . . . . 4 acres.

- Asparagus . . . . . 3 1/2 acres.

- Cabbages . . . . . 1 acre.

- Turnips, carrots, etc. . . . . . 3 acres.

- Snap beans . . . . . 2 acres.

- Oats sowed with clover . . . . . 8 acres.

- Garden vegetables . . . . . 2 1/2 acres.

- Broom-corn . . . . . 1/2 acre.

- Strawberries . . . . . 1/2 acre.

- Peach orchard (800 trees) . . . . . 6 acres.

- Pear orchard and nursery . . . . . 2 acres.

- Cherry and plum orchard . . . . . 2 acres.

- Apple orchard . . . . . 4 acres.

THE PRINTING-OFFICE.

The printing-office connected with the school was founded by the gift of one thousand dollars from Mrs. Augustus Hemenway, of Boston, and was opened for business November

Page 44

1st, 1871, beginning with two small presses, a second-hand Washington hand-press, and a quarter-medium Gordon press, to which was added last winter, by the liberality of Messrs. Richard Hoe & Co., of New-York, a first-class hand stop cylinder press, a gift of very great value to the school. About the same time, a donation of nearly three hundred dollars' worth of new type was made by Messrs. Farmer, Little & Co., New-York. These generous gifts have greatly increased the working facilities of the office, which is the only one in Hampton. By the job-work which it is thus able to take in, it is established upon a paying basis, as well as enabled to offer greater advantages of work to the students. The boys employed in the office are selected as showing particular aptitude for the business, and the majority of them make rapid progress--one indeed having been able during the past year to pay his way in school by work done out of school hours.

The first cost of the office and its furniture was paid by

friends in the North, and the neighborhood affords a fair regular

supply of job-work, while an illustrated paper, The Southern Workman, is published monthly, for circulation among the industrial

classes of the South, among whom it has met with

a very favorable reception.*

*See Note 3 in Appendix.

In addition to their training on the farm and in the printing office, the male students are employed in the carpenter and blacksmith-shops, shoe-shop and paint-shop, where most of the ordinary repairs and light work of the establishment are done. These different departments of manual labor furnish such variety of instruction as admirably prepares the students for the uncertainty of their future lives, and enables them at the

Page 45

end of the three years' course to choose between several occupations, in any one of which they can serve with honor and profit to themselves.

GIRLS' INDUSTRIAL ROOM.

The young women of the school are also provided with an Industrial Department (founded by a Northern lady), where they are taught to cut and fit garments, and to use various sewing-machines, the articles which they produce being sold to members of the school or to persons in the neighborhood; and the report of the founder of this department is, that "the young women employed are in most cases faithful and industrious, eager and grateful for the opportunity of earning something toward their expenses, while their spirit and conduct in connection with the department have, except in a few cases, been good in all respects." In addition to the special work of this

Page 46

department, the girls are taught the ordinary duties of a household, laundry-work, etc., and are thus fitted to become cleanly and thrifty housekeepers, while their personal habits are carefully superintended, and they are constantly instructed in the simpler laws of health.

The labor performed by the students during the last two years and its results are so essential a part of the school's history, that the following extract from the Treasurer's report is given, as embodying statistics of real value:

SESSION OF 1871-2.

- Students on labor list . . . . . 95

CREDITS FOR LABOR.

- On farm . . . . . $1,360 01

- Boarding Department (house-work) . . . . . 1,087 35

- Girls' Industrial Department (sewing, etc.) . . . . . 625 03

- School-work (accountants, janitors, carpenters, etc.) . . . . . 826 01

- Shoemakers . . . . . 74 95

- Printing-office . . . . . 280 62

Total . . . . . $4,253 97

SESSION OF 1872-3.

- Students on labor list . . . . . 170

CREDITS FOR LABOR.

- On farm . . . . . $1,873 93

- Boarding Department (house-work) . . . . . 1,408 90

- Girls' Industrial Department (sewing) . . . . . 701 08

- Printing-office . . . . . 239 91

- School-work (accountants, janitors, carpenters, etc.) . . . . . 1,018 62

- Shoemakers . . . . . 86 37

- Work on buildings . . . . . 53 26

Total . . . . . $5,382 07

The rates of credit for labor are adjusted according to its market value, and the training which the students receive in the

Page 47

thorough examination and understanding of their accounts, which are made out in detail monthly by the Treasurer, is of permanent and incalculable benefit to them.

One of the fundamental principles of the school is that nothing should be given which can be earned or in any way supplied by the pupil, and in consonance with this principle, regular personal expenses for board, etc., rated at $10 a month, are thrown upon each student, to be paid by them, half in cash and half in labor. Good mechanics, first-rate farm-hands and seamstresses can earn the whole of this amount, but those pupils whose labor is of little value, and who are destitute, being either orphaned or with impoverished parents, require and receive proper aid, nearly one third of the boarders having been assisted by direct donations during the past term. To this purpose are devoted the annual income from the "Peabody Fund" of $800, and such part of the cash receipts of the school as may be found necessary; personal relief being made systematically exceptional and closely contingent upon high merit.

Among the most prominent dispensers of such aid are Mr. and Mrs. George Dixon, of the English Society of Friends, and during six years teachers among the freedmen in the South, at their own charges. They are now giving personal aid to forty-five of their former pupils as members of this institution. To this end, they have secured funds by personal effort in England. Mr. Dixon was for twenty-five years head of the Agricultural College at Great Ayton, Yorkshire, England, and now, as a resident on the Normal School premises, and lecturer on Agricultural Chemistry, adds very materially to the resources of the faculty.

While every thing is thus done to cultivate a spirit of self-reliance and independence, it has been proved, as a matter of

Page 48

fact, that beyond this payment of actual personal expenses, the colored youth of the South are not able to go. These young men and women at Hampton strain every nerve to meet the daily cost of their food and clothing, and it is beyond a doubt that if they are to get any education at all, such education must be given to them. Instruction, therefore, is the central point of our work, and entails the chief outlay, to meet which, the actual cost of educating each individual, estimated at $70 per annum, has to be secured by voluntary contributions. In order, therefore, to keep up that practical, personal interest in the school which, so long as it depends upon private charity, is of the first importance, a system of scholarships has been instituted and found to be most successful.

These scholarships are divided as follows: Annual scholarships of $70, scholarships for the course of three years of $210, and permanent scholarships of $1000, the interest of which is forever devoted to the education of a pupil. Last year, 152 annual (or $70) scholarships were contributed, many of the donors of which have signified their intention to renew them, thus meeting the heaviest present expense of the school; but the desire of the trustees is to establish, as rapidly as possible, permanent (or $1000) scholarships, and a number of professorships, of from $10,000 to $25,000 each, which will save the time and cost of annual collections, and insure the future of the institution.

The Rev. Thomas K. Fessenden, of Farmington, Ct., over two years ago undertook the work of securing an endowment. His efforts have been successful beyond expectation (see note in Treasurer's report in Appendix); and in this connection, it is not out of place to mention that Mr. Fessenden is the founder of the Girls' Industrial School at Middletown, one of

Page 49

the noblest charities in Connecticut. As a member of the Legislature of that State, his influence secured the passage of a satisfactory law in behalf of that school, and his personal solicitations resulted in an endowment of nearly $100,000 for it.