Forget-me-nots of the Civil War;

A

Romance, Containing Reminiscences and Original Letters

of Two

Confederate Soldiers

:

Electronic Edition.

Lee, Laura Elizabeth

(Battle, Laura

Elizabeth Lee)

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital

Library Competition

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Carlene Hempel

Images scanned by

Carlene Hempel

Text encoded by

Heather Bumbalough and Natalia Smith

First edition,

1998

ca. 550K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number C970.78 B33f c.3 c1909 (North Carolina Collection, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition is

a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project,

Documenting the American South,

Beginnings to 1920.

Any hyphens occurring in

line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks and

ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right

and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right

and left quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines has

not been preserved.

Running titles have not

been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject

Headings,

19th edition, 1996

- LC Subject Headings:

-

- Battle, Laura Elizabeth Lee.

-

- Women -- North Carolina -- Biography.

-

- North Carolina -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives.

-

- North Carolina -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Women.

-

- Confederate States of America. Army. North Carolina Infantry Regiment, 4th. Company F.

-

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Military life.

-

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- 1998-10-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-10-08,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-10-07,

Heather Bumbalough

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-09-22,

Carlene Hempel

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

FORGET - ME - NOTS OF

THE CIVIL WAR

A ROMANCE,

CONTAINING REMINISCENCES AND ORIGINAL LETTERS

OF TWO CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS.

BY

LAURA ELIZABETH LEE

ILLUSTRATED BY

BRYAN BURNES

All rights reserved

ST. LOUIS, MO.

PRESS A. R. FLEMING PRINTING CO

COPYRIGHT 1909

By

MRS. JESSE MERCER BATTLE

TO JESSE, THE HUSBAND,

WHO IS STILL MY BOY LOVER,

TO HELEN, THE DUTIFUL DAUGHTER,

WHO HAS BEEN THE LINK TO WELD MORE

CLOSELY OUR LOVE,

AND WHOSE LIVES I HAVE WANTED

TO FILL WITH SUNSHINE,

BUT WHERE THE SHADOWS HAVE OFTEN CREPT,

THIS VOLUME IS LOVINGLY DEDICATED.

MAY ITS PAGES BE ILLUMINATED BY THEIR

LOVE AND INSPIRATION.

LAURA ELIZABETH LEE.

Page 5

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER

- I. My Arrival at "White Oaks" . . . . .

9

- II. Some of the Things That Happened . . . . .

17

- III. Our Removal to Clayton . . . . . 23

- IV. The Attempt to "Tar and Feather"

My Father . . . . . 29

- V. The Year Eighteen Sixty-one . . . . . 33

- VI. The Gallant Fourth N. C. Regiment,

State Troops . . . . . 37

- VII. Letters from George and Walter . . . . . 41

- VIII. My First School Days . . . . . 135

- IX. My Father's Death and Burial . . . . .

139

- X. How the Sheriff Swindled My

Mother . . . . . 147

- XI. The Work We All Did During the

War . . . . . 155

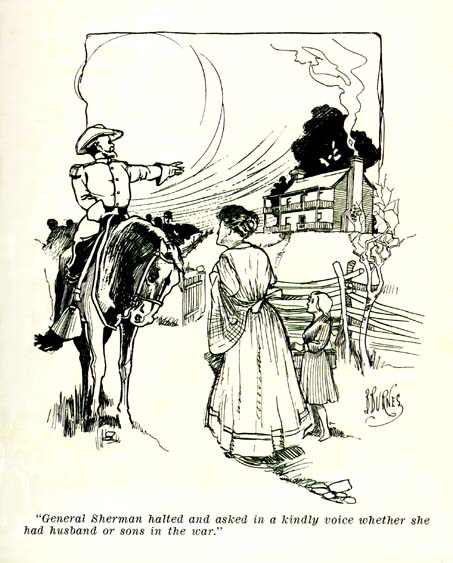

- XII. Sherman's March to Raleigh, North

Carolina . . . . . 159

- XIII. The "Bummers" and "Red Strings" . . . . .

165

- XIV. The "Ku Klux Klan" . . . . . 171

Page 6

- CHAPTER

- XV. How I First Met "Uncle Ned" . . . . . 177

- XVI. The Beautiful Pink Frock . . . . . 191

- XVII. My First Great Sacrifice . . . . . 199

- XVIII. The State Tournament . . . . . 207

- XIX. The Great Race . . . . . 217

- XX. The Crowning of Nealie For Queen . . . . . 229

- XXI. The Coronation Ball . . . . . 235

- XXII. The Marriage of Ashley and Nealie . . . . . 241

- XXIII. The Conquering Hero Comes . . . . . 247

- XXIV. The Baptizing at Stallings Mill . . . . . 255

- XXV. The Meeting at the Well . . . . . 261

- XXVI. Jesse Falls in Love at First Sight . . . . . 265

- XXVII. I Am Not Far Behind . . . . . 271

- XXVIII. His Departure and My Grief . . . . . 275

- XXIX. Hear Rumor of Engagement to

Another Girl . . . . . 281

- XXX. I Am Very Unhappy . . . . . 285

- XXXI. Our Engagement . . . . . 291

- XXXII. One Evening's Entertainment . . . . . 299

- XXXIII. How My Mother Disposed of Us . . . . . 335

- XXXIV. Jesse's Enforced Absence . . . . . 341

- XXXV. My Mother Makes Us Happy at Last . . . . . 351

Page 7

Page 6

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- Mrs. Jesse Mercer Battle (Laura Elizabeth Lee) Frontispiece

- "Aunt Pallas." . . . . . 10

- George . . . . . 42

- Walter . . . . . 132a

- "General Sherman halted and asked in a kindly

voice whether she had husband or sons

in the war." . . . . . 160

- "Uncle Ned." . . . . . 178

- Nealie and the Pink Frock. . . . . . 192

- "Uncle Ned's" Return. . . . . . 195

- "Dropped the wreath at my sister's feet." . . . . . 236

- "Give the horses the reins, Henderson, and

let them go the road they will." . . . . . 248

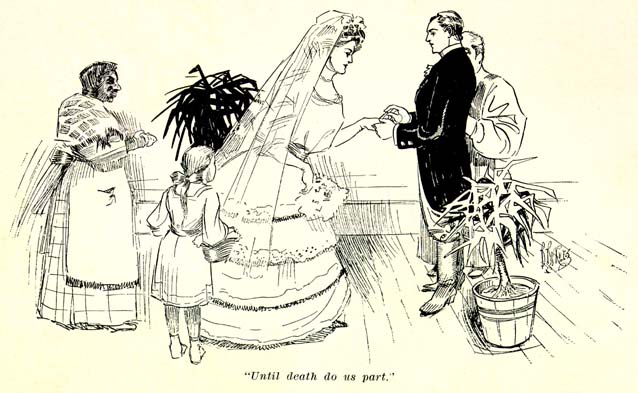

- "Until death do us part." . . . . . 352

Page 8

"The

dainty architects of prose and rhyme

Have

their brief niches in the Hall of Time;

But

he is master of the deathless pen,

Whose

words are written in the lives of men."

- WILLIAM H. HAYNE.

Page 9

CHAPTER I.

MY ARRIVAL AT "WHITE OAKS."

On

the twenty-sixth day of January, eighteen fifty-five,

I first saw the light. The day was cold and

raw, with snow flurries now and then filling the air.

It is not to be wondered at that my arrival was not more warmly welcomed, as it was the most unusual thing for snow to fall in that warm southern climate. Being the youngest of eleven children, also made the advent of another girl baby a source of indifference to the inmates of "White Oaks," the name by which our place was known.

The children were assembled for their noonday meal on this eventful day in the dining room where they were discussing the new baby and attempting the difficult task of finding a name, one that was not already in the family Bible or had not been in use in the family generations before. After many names had been rejected and scorned as unfit, Nealie cried out "Oh, let's name the baby Bettie!" The boys not caring one way or the other acquiesced immediately, but Flora implored them "No, no, not Bettie, call her Laura." While Rilia, then fourteen, and feeling quite motherly to all, declared they should compromise and call me "Laura Bettie," which suggestion quite satisfied them

Page 10

all, both boys and girls. Rilia was then deputized to visit the nurse, Aunt Pallas, and beg that this name be submitted to my mother, as pleasing all the children. She soon returned with the glad tidings that "Laura Bettie" would be enrolled in the old family Bible, which was well nigh filled, as "Laura Elizabeth," that being more suitable for me in later years, but she said "Lookee heah, chillun, you can call dat baby poah little ugly thing 'Bettie' or 'Laura,' but I'll do her laik I did 'Pussie' (her pet name for Cornelia), I'm a' gwine to call her Betsy." So it was settled by them, and from then on I was called by each of those names as each member of the family or friend happened to think of first.

Aunt Pallas, whom you will meet throughout the pages of this book, was a typical African in color, though her head was larger than the average negro, with the kinky hair growing low on her forehead, her eyes were very small, but lighted up by intelligence. Her nose was large and flat, and most decidedly gave the appearance of a full-blooded native of Africa. Her mouth was large, with full lips even adding to her homeliness. Her shoulders were square, the body and hips with straight lines like a man's. Her limbs were muscular and her stature, though short, was as erect as a young Indian's. She claimed that she made herself so by carrying pails of water on her head when she was a child.

"I declare before goodness," she used to say, "that Col. Johnnie Hinton bought my mammy from some niggah traders, dat told him mammy was a guinea niggah

Page 11

and b'longed to de quality, an dats why she called me Pallas - dey shore did get my name out of the dicshummary." Her homeliness was so marked that it really helped to make her attractive. Her age, like every other one of her race, was a problem we never could guess, except from bits of history that she would tell us. She remembered when George Washington died, and many incidents of the Revolutionary war.

Our large family lived on the farm called "White Oaks," near a small town called Clayton. The land my father planted in grain at that time, and as the soil was later found suitable for cotton he and the boys had hard times "making both ends meet." Two of the older boys had married, leaving the burden on him and the younger sons. He was well advanced in years at this time. My father was a typical Southern gentleman, with a courtly dignified bearing, and was well educated for the times. He was a descendant from that illustrious Virginia family whose lives have been recorded on the pages of American history since the Colony of Virginia first had a Secretary of State, and before his marriage had taught school in the town near his present home. It was there that he met and married the daughter of a wealthy planter and a large slave owner. Being an ardent abolitionist he refused the gift of a young negro man and his wife on his marriage to Candace Hinton. This refusal, coupled with his outspoken convictions never to own slaves, made him a target for the slave owners in that section. It is true that "Aunt Pallas" was a maid for his first wife, and was so devoted to her

Page 12

that she was no more a slave than the wife, and was permitted to do exactly as she pleased. When the rumor spread abroad that Charles Lee was a rank abolitionist there were already war clouds that bid fair to darken the whole fair South-land; his father-in-law, Col. John Hinton, forbade him ever "darkening his doors." Whether the estrangement had anything to do with a decline in her health, the wife soon sickened and died, leaving behind her seven children, all except two greatly in need of a mother's love and tender care.

My father soon began casting about to find some one who would be a mother to his babies. He had known my mother as an acquaintance a few years, and his wife always spoke so kindly of her and her great beauty - that may have helped him to turn his footsteps toward her home. My mother, also named Candace Hawkins Turley, was a woman remarkably beautiful, but whose family was obscure, excepting her grandfather, Thomas Turley, who was a Revolutionary soldier when the war for American Independence began; he enlisted on the patriot side, and served from the beginning of the Revolution to the siege of Yorktown, at which place he was made an invalid for life by the bursting of a British bomb shell near his head. The story of his abduction when a baby, as handed down, made interesting family history; he was born in Ireland, and belonged to the Irish nobility. As was the custom in such families, the children were entrusted to white nurses, who became strongly attached to their charges. Thomas Turley's nurse having

Page 13

decided to emigrate to America, could not endure the separation, and he was stolen by this woman and reared by her in America.

This child never knew the secret of his life until divulged by his old nurse on her deathbed. It was said that he did not know his own name, as this woman so much feared that her guilt might be known and the child restored to his seeking parents.

It is not strange that my mother's family was obscure with such a bit of family history. My father must have had in mind, to avoid another estrangement if he should attempt to marry again, another slave owner's daughter. That my mother married him for love goes without saying. My father then being over sixty years old, had that to his disadvantage, though his genial, kind nature, together with his scholarly attainments and his descent from an old Virginia family, no doubt added to his other attractions, and caused my mother to hasten to be the wife of a widower, now growing old, whose sole wealth was a ready-made family, excepting, of course, the farm of "White Oaks." It was even whispered then that he had consumption and would not live five years longer.

My mother was a woman so strikingly handsome that I shall not attempt more than a few words of description. She was an Irish type of beauty, above the medium height, with beautiful wavy brown hair, a broad low brow, a classical Grecian nose; her eyes of grey, were large and seemed unfathomable; her mouth a perfect cupid bow, and ruby lips through which shone pearl-like teeth, an oval face, with perfect

Page 14

chin and ears, moulded on a neck of alabaster whiteness; her pink cheeks glowed with health, her complexion was marvellously fair, and the blue veins showed their delicate tracery beneath a skin of polished smoothness. A Madonna like face was my mother's. There was nothing insipid in my mother's beauty; it was a beauty of strength of mind, that shone out on her noble mien, whether the tradition in regard to her descent from the Irish nobility were true or not, hers was a face of such uncommon beauty that obscure birth could not hide the breeding and noble race from which she sprang. Her very carriage bespoke grace and dignity, with a firmness of purpose that once she had taken hold of the plowshare, it would take nothing less than victory to cause her to drop it. Still there was nothing obstinate in her appearance, only a resolute face and figure that radiated a beautiful character in every suggestion.

Page 16

For, lo! my love doth in herself contain

All this world's riches that may be found;

If sapphires, lo! her eyes be sapphires plain;

If rubies, lo! her lips be rubies sound;

If pearls, her teeth be pearls, both pure and round;

If ivory, her forehead Ivory ween;

If gold, her locks are finest gold on ground;

But that which fairest is, but few behold,

Her mind, adorned with virtues manifold.

- EDMUND SPENSER.

Page 17

CHAPTER II.

SOME OF THE THINGS THAT HAPPENED.

Well, somehow, widowers are more expeditious in such matters, and after a very short courtship they were married, and Candace Hawkins Turley went to be mother and mistress of "White Oaks."

The time passed rapidly, filled with work and many cares, and in five years she was the mother of four children, three girls, one of whom died, and one boy.

They continued to live on the farm, though father had no turn for farming; the poor land and the large family made work enough for all, and a slave of my mother. The older children were sometimes required to look after me and their manner of amusing me was at times very peculiar. I was told that on one occasion when I was about ten months old father took mother to church, at "Old Liberty," five miles distant, Rilia, my half sister, and Nealie, the oldest of my mother's children, took me out to the barn where a pile of raw cotton had been thrown, reaching up to the ceiling. These sisters of mine, wishing to stop my cries for my mother, began to toss me up on the pile of cotton and let me roll down to the floor where they were carefully stationed to catch me. It gave me great delight, and I set up such crowing

Page 18

and laughing that it gave such zest to the pastime that I began to laugh and crow louder. I suspect now that my brains were being well addled, but any way the more I laughed, the more I was kept tobogganing until in a careless way Rilia threw me up and I went clear over the top of the pile of cotton, rolled down and struck a beam on the other side. Immediately I set up such a scream that with great alarm they carried me back to the house where Aunt Pallas discovered a sprained wrist and a dislocated shoulder. It took hours in those days to drive five miles to church and return, so my cries well night drove my poor sisters wild, until my father returned and set the bones. My poor mother declared it happened just because she left me at home, and did not intend to ever do so again. Still she and father were good Baptists and could not resist the monthly meetings, at "Old Liberty" Church, and there were many other times when I was left behind.

On another occasion the older children had me in charge again, and decided upon another novel way of amusing me. We were all playing in a large room with a big high white bed in it, Nealie, after while, said: "Suppose we amuse Bettie by making pictures for her," then turning to me, she asked: "Wouldn't you like for sisters to make some pretty pictures for baby to look at?" I smiled and cried "Yes," whereupon the two held a whispered conversation and immediately they made a dash for the fire place, and placing their little white hands on the back of the fire place that was all

Page 19

covered in soot, ran to the bed and began laying their hands on the pretty white counterpane trying to draw pictures of dogs and people. I was the audience and had a seat in the rear of the room, but not wishing to sit there, while such works of art were being placed before me, I up and toddled over to the bed and began to investigate. Imagine my consternation on seeing my sisters begin to turn black before my eyes, so I thought I'd rub the black off them, when lo, I began to turn black too. Well, in a short time the whole bunch of us were black and weird-looking. I was so frightened I could hardly speak when the door opened and father and my mother came in, and I think the rod was not spared, on seeing the snow white counterpane, covered in grotesque pictures and little finger prints, even the walls were decorated to suit the taste of the embryonic artists.

My first recollections of going to church at "Old Liberty" were of being dressed up and riding with father and mother in the barouche till we came to a deserted looking house, standing by itself in a big grove of trees. Then my mother led me around to the side of this house where a great many ladies and children were sitting down on a bench. After a while the door was unlocked and we all went inside. The men all sat to themselves on one side and the women and children sat on the other side of the room. Then they all began to sing such a sleepy song, I dozed off, but dreamily heard a man talking, and once in a while he would shout so loud I'd awaken with a start, to drop off to sleep again, my head resting on my mother's

Page 20

lap. I awoke after a long time and saw a man handing a plate to everybody, to take something to eat, Oh! how glad I felt, but when my mother broke only one tiny bite and then ate that, without even looking at me, I was getting ready to weep, but when another man came up with a silver goblet and she took a drink and didn't look at me again, I gave one loud wail and begged for a drink too; not only denied that, but taken in her arms and toted out of the church, before everybody. Then the cookies were found and a nice gourd of cool water from the spring was given me, and we went back home. I was old enough to know why I was not permitted to partake of the Lord's Supper the next time I went to "Old Liberty."

Page 22

A little elbow leans upon your knee,

Your tired knee that has so much to bear;

A child's dear eyes are looking lovingly

From underneath a thatch of tangled hair,

Perhaps you do not heed the velvet touch,

Of warm, moist fingers folding yours so tight,

You do not prize this blessing over-much,

You almost are too tired to pray tonight.

- ANONYMOUS

Page 23

CHAPTER III.

OUR REMOVAL TO CLAYTON.

One day when father had returned from the corn field my mother said to him, "Mr. Lee, I wish you would move to Clayton where we will be near enough to a school for the little children to go by themselves." "Why, 'old woman' (calling her by his pet name for my mother), "what shall I do with the farm?" "Rent it," said my mother, "start up the old saw mill in Clayton, build a home there for us to live in; I hear that a great many people are anxious to move there if they could only get the lumber to build with. We have plenty of seasoned lumber," she continued, "to build a home for us. Since some of the older children are married it makes the work too hard on you. The small children ought to be in school every day, and here we have to send them and send after them and many times the weather is so bad they don't go at all. If we move to town there will be no excuse for staying at home. When you have set up the saw mill and supplied everybody with lumber for building, you can take your money, and with some I had before we were married, start some kind of a mercantile business in this thriving little town. The rent from the farm will put us in easy circumstances. This money I have had for so long I intended to buy

Page 24

with it a couple of young negroes to work this land and increase their progeny. Knowing your feelings I have nothing else to do but submit to your will, though it has been a long cherished dream of mine to use my money to buy slaves."

"Now 'old woman,' I decline to discuss this slavery question again. I will never own another slave (if you call Pallas such), and only pray that this talk among the Northern statesmen may not end without good results. No I will never buy a human soul with money," emphatically declared my father. "So talk no more about that, but your other proposition I believe is a good one, and I will go to Clayton tomorrow and see what I can do." My mother who had lived in town before her marriage and was never pleased to live on the farm, was delighted at the prospect of a change to town.

Father went to Clayton the next day, bought a lot and built a home and moved his family there within the next year.

Clayton was beautifully situated. Nature had been most lavish in her gifts. The hills, upon which the town was built, gave a most picturesque look to the undulating country for miles around, if the view had not been obstructed by the tall pines and majestic oaks that stood like sentinels to guard the lovely spot. Flowers bloomed perpetually though there came nipping frosts now and then which made malaria and fever give it a "wide berth." The atmosphere was always so dry that it gave one a feeling that it had just come from the hands of its maker, so pure and clean it appeared. The climate reached the happy

Page 25

medium in winter and summer alike, it was never enervating, for the ozone from the pine forests and the oxygen that the grand old oaks set free gave health and rosy cheeks to the children that roamed around the little town. The streets were not paved, but like the beach drives at the sea shore, were hard and white, as if made of crystalline powder - and for racing purposes gave the horses a firm footing though cushioned and yielding. The water was noted for its purity and health-giving qualities. Take it altogether Clayton seemed to be about the "garden spot" of the "Old North States," so far as what nature had done for it. On one side of the town were the "sunny banks of the rippling Neuse," inviting alike to fisherman and picnicker. The other side was bordered by "Little Creek," a limped stream filled with silver perch. Added to these charms was the old Academy for boys and girls, with its two large play grounds which had more to do with our removal there than anything that nature might have offered.

When father moved to Clayton, the mill did such a good business that he was kept busy for five years. In the meantime he bought pieces of land here and there about town and with the money he made from milling he bought a stock of goods and groceries and established a mercantile business.

The war clouds were growing blacker and threatened to end in something more than "talk."

He continued to talk against slavery, and the slave owners began to fear that he might be a disturbing element if let alone. One day father received an anonymous letter, saying if he did not stop this talk

Page 26

against slavery, that he would be "tarred and feathered and ridden out of town on a fence rail."

He was then in very delicate health, and when he came home and told my mother about this note she was greatly agitated and said, "Why, Mr. Lee, what shall we do, move back to the farm or what in the world will you do?"

" 'Old woman' I shall stay right here and do my work for I do not fear these men who are too cowardly to sign their names to the letter of threats."

"Oh suppose they should try to carry out their diabolical plot. I don't think we ought to stay here, really 'White Oaks' is the only safe place. Come let us move tomorrow."

"Never," said my father, very calmly but very firmly too. "I am not a coward, for I inherit a love of my country from my ancestors who helped to establish independence in these colonies, but slavery and its evils I forsee will precipitate another war for the freedom of another race. I do not fear these threats for the writers of this anonymous letter dare not do what they no doubt would like to do, for such a thing would be heralded from Maine to Texas, and my life, though a forfeit, would help to free the slaves, even sooner than I now think will be."

"Well, Mr. Lee, I can't help but fear all the same such underhand work. It is not the foe we meet face to face, but the enemy that slips upon us unawares," persisted my poor mother. "I dare not permit myself to think of this horrible deed without being alarmed and fearing for your safety. I shall keep a

Page 27

close watch over you and not let you get far from me," insisted mother.

"Well, 'old woman,' this cough means that my days are numbered. I want to make my will and arrange all my worldly affairs, so as to give you as little trouble as possible. I want to leave you with the business in good shape, knowing your fine executive ability, so that everything will continue to run smoothly. I am resigned to God's will, but hate to leave you, my faithful wife, with the five small children." Here my mother began to cry, "Oh don't speak of leaving me and the children, I can't bear to hear you say it," and thereupon she broke down again.

"Well, 'old woman,' this is a matter of business; that you should know we are doing well in the store and the farm is paying better than I ever hoped for. Raising cotton has been more profitable, with the Jones tenants, than my poor efforts at raising grain ever were, besides bringing much higher prices."

However the days and nights were spent in horror to my mother, though she tried to hide it from father; the fear of those men doing that dastardly deed, and the knowledge that father was daily growing worse, made poor mother old before her time. I remember going day after day with her to the store where she sat and sewed, always near the door, and scanning every one as they came in, her face wearing a set look and a determined one, and I now think after more than forty years have passed that it was her presence, always near my father, that helped to hinder those fanatics from perpetrating that black crime.

Page 28

We live in deed, not years; in thoughts, not breath;

In feelings, not in figures on a dial.

We should count time by heart throbs where they beat

For God, for man, for duty; He most lives

Who thinks most, feels the noblest, acts the best;

Life is but a means unto an end, that end

Beginning, mean and end to all things, God.

- P. J. BAILEY.

Page 29

CHAPTER IV.

THE ATTEMPT TO "TAR AND FEATHER" MY FATHER.

My two half brothers, Walter and George, were as rank secessionists as my father was abolitionist. Though only fifteen and seventeen years of age, these boys had inherited from Col. John Hinton, their maternal grandfather, a desire to own slaves, and always declared when they were old enough that they would have negroes to work for them. Still the main reason for their being secessionists was that all their companions were drilling and talking of war all the time. Aunt Pallas having heard my mother tell of the note to my father, in which he was to be "tarred and feathered and ridden on a rail out of town," was so distressed that she told Walter and George to get out the old guns and put them in good condition, that they didn't need to go off to shoot Yankees on account of the trifling niggers. "I'll tell ye what we will do, when anybody comes round heah looking for Marse Charles we will take our guns and load up with powder and go out and fire 'em off, he! he! I'll be seized by cats, but dey nevah will try to ride any other gentleman on a rail."

The boys were so angry at the bare mention of such treatment for their good father that it was all

Page 30

Aunt Pallas could do to keep Walter and George from putting in bullets to kill somebody. At last she persuaded them not to do it, still they "kept their powder dry" and waited.

One beautiful moonlight night some one came to our front door and knocked. One of the boys went to open it and found waiting outside a negro boy, owned by one of our near neighbors, who said "my master sent me to ax your daddy to come out to de store and let me have a bottle of castor ile, for brudder Reuben, he got de colok." Aunt Pallas had posted Walter and George that when they heard her singing "My head got wet wid de midnight dew, honah de lam, good Lawd honah de lam," they might know that the posse were out after father. Before Walter had time to go to father with the message Aunt Pallas began to sing "Honah de lam" and both boys darted out to the place where the guns were hidden, and with Aunt Pallas leading the little army they made a rush for the big oaks, and standing back of them they began to discharge the old guns. At the first shot such consternation seized these villains that the whole posse stampeded and such running as they did has never been seen before or since in that dignified old town of Clayton. Of course Aunt Pallas and the boys ran after them and continued to explode their powder, but so effectually did the explosions work that no more attempts were ever made on my father's life.

Page 32

In war not crafty, but in battle bold,

No wealth I value, and I shun all gold.

Be steel the only metal shall decree

The fate of empire, or to you or me.

The generous conquest be by courage tried,

And all the captives on the Roman side,

I swear by all the gods of open war,

As fate their lives, their freedom I will spare.

- PYRRHUS.

Page 33

CHAPTER V.

THE YEAR EIGHTEEN SIXTY-ONE.

The year eighteen sixty-one was ushered in with loud mutterings of war, and among my earliest recollections were those of seeing a body of men drilling in front of our home. These militia companies were being formed in every county, and the women and girls were meeting in halls or school houses for the purpose of sewing on flags and uniforms for the men and boys, that later became soldiers. Everywhere was heard the talk of war, even the small boys were hoping for the time to come when they might be allowed to shoulder a gun and go off to shoot "Yankees." One day on our way home from school, some one told us that Fort Sumter had been fired on, that was even unintelligible to me, but greatly pleased my brother George, for he threw up his cap and howled, "Hurrah for South Carolina, I am going to be a soldier now."

My father was so feeble that when Walter and George declared their intention of volunteering he could not show them by his arguments that they were wrong, and knowing, too, that his days were numbered, felt that only a short time and they would be at liberty to go to the war. From morning till night was heard fife and drum, or the talk of the citizens

Page 34

that preparations were being made all over the South for a contest which would soon end in favor of States' rights. Shortly trains loaded with men going to enlist, and soldiers, kept the young people running to the depot to see the different regiments. Everyone had a flag which was waved as the trains passed our town. Sometimes they made no stop at the station, but the girls had notes of encouragement written and placed between split sticks, and as the cars went by the girls would throw their missives of faith and hope to these strangers. When the ladies were sewing on the uniforms the girls would write notes and put them in the pockets of the soldiers' jackets. In these they would write and beg the wearer to be true to his colors and his country, and never despair until the last Yankee had been whipped. Like "bread cast upon the waters" the soldier boys read and were inspired with courage to go on, and very many correspondences begun like that, ripened in later years into love and marriage.

Page 36

And far from over the distance

The faltering echoes come -

Of the flying blast of the trumpet,

And the rattling roll of drum;

Then the Grandsire speaks in a whisper,

"The end no man can see:

But we give him to his country,

And we give our prayers to Thee."

- WILLIAM WINTER.

Page 37

CHAPTER VI.

THE GALLANT FOURTH NORTH CAROLINA REGIMENT

STATE TROOPS.

The day that the gallant "Fourth North Carolina Regiment" passed our town my half brothers, Walter and George, bade us all goodbye amid tears and hurrahs, bands playing and the crowd singing, "Shout the joyous notes of freedom" and off to the war they went. They had spent some little time at Fort Macon, but now they were on their way to Richmond and death. Some of their letters have been preserved up to this time; they were written on scraps of writing paper and sometimes cheapest wrapping paper. It may be interesting to publish them for future generations, to know exactly what two young Southern boys thought of war in the beginning, and how one, at least, throughout those terrible battles at Spottsylvania Court House, etc., lasted to give us such a vivid description of them, and I have written them verbatim from the original letters, and know nothing was exaggerated from their view point. This extract from the letter of a friend shows how fine looking and soldierly in bearing these brave men and boys of the Fourth North Carolina were considered by a

Page 38

friend who saw them in Richmond soon after their arrival.

""The Fourth North Carolina Regiment" is the recipient of unmeasured praise for their deportment while on leave and their soldierly bearing in the ranks. In fact not a regiment has come from our state that has not elicited unstinted commendation for their fine appearance. It does me good to stand in a crowd as I did on Sunday when the "Fourth" passed through the streets and hear the hearty words of satisfaction expressed as to the material, the "Old North State" was sending into the field. Such expressions as "Did you ever see such determined looking fellows, steady, cool and resolute looking?" "What should we fear while such as these are between Richmond and the enemy?" I assure you I felt like giving one uproarious shout for the "Old North State" forever. I enclose you a rare curiosity, being the Federal version of the glorious battle at Manassas. It is a curiosity, inasmuch as no instance is known where a Lincolnite has put so many words together with so few monstrous discrepancies spicing the whole, and I have marked them, under the influence of the panic which such news created. A greater proportion of truth bubbled forth than usually characterizes their accounts of such disasters to their arms."

Richmond, July 23, 1861.

ROBERTSON.

Page 40

"Be of good cheer; your cause belongs

To Him who can avenge your wrongs;

Leave it to Him, our Lord.

Though hidden from our longing eyes,

He sees the Gideon who shall rise

To save us, and His Word."

- MICHAEL ALTENBURG.

Page 41

CHAPTER VII.

LETTERS FROM GEORGE AND WALTER.

FORT MACON, N. C., April 19, 1861.

Dear Mother:

Our company

arrived here this morning at 8 o'clock.

We had to stay at Beaufort last night, the water being too

rough to carry us over last night. I intended to have

written last night while at Beaufort, but we were so

completely worn out with hollowing, etc., that all of us got

to bed as soon as possible, which was about 12 o'clock.

We have been employed a little while this morning

carrying barrels, etc. It was raining the whole time. They

make no difference here for rain or anything else.

There is only about two or three hundred men here as yet. There are more men expected daily. Our company is the largest, the best looking (so said by the men here), that there is in the Fort.

George and Tom Stith are down on the beach shooting porpoises. I had to borrow this piece of paper to write to you, George having the paper in his valise.

The company has this evening to look around. Tomorrow we have to commence drilling. George has just come in. He says he had lots of fun, and told

Page 42

me to tell you that he would write to you tomorrow. He found a good many curious looking shells, which he has put in his valise, to carry home. Blake asked me to say to Mr. Rhodes that he was very well satisfied, indeed. The whole company is enjoying themselves very much. I will write to you again as soon as I hear from you. Please write to me often. Direct to Fort Macon, care of Capt. Jesse Barnes. Your affectionate son, till death,

WALTER.

FORT MACON, N. C., April 28, '61.

Dear Mother:

As there is a man going by Clayton tomorrow I

thought I would write you a few lines, to let you know

how we are getting along. We are enjoying ourselves

as well as can be expected. We had prayers and singing

this morning by Mr. Cobb. He spoke of the injuries

of the South in an eloquent manner.

For the last day or two we have been living on the victuals that the people sent down here. The first few days we had bread, butter, etc., but as they have given out we live on bread, fat meat and coffee. If Blake does not tell you, I wish you would please send Walter and me a cooked ham and some biscuits, with a few of those small round cakes, for the cakes that are sent down here for the company are usually taken care of by the officers and are hardly seen by the privates. Walter is upon his bunk enjoying himself finely and sends his love to you. I am going to try to get a furlough to go home before long, for I long to be home

Page 43

with you all. * * * I forgot to tell you that we did not have to drill or work either this Sunday like we did the last. You spoke of sending a mattress down to us, but you need not for we are getting along very well. We are ordered to stay down here three months without lief to go home in the meantime, so Col. Tew says. Believe me as ever

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

CAMP HILL, N. C., July 9, 1861.

Dear Mother:

We arrived

here about night, the day we left Wilson,

and having raised our tents prepared to get supper,

which we got about 9 o'clock. We are encamped

in an old pine field, which is very hot, but the other

companies that were here before have a very pleasant

oak grove on a hill. The Second regiment, under

Col. Tew, are on the opposite side of the road. Our

Col. Anderson is a fine looking man, about six feet

high, large and muscular, but not corpulent; a high,

broad and intellectual forehead, bold face, and whiskers

(shaped like Walter's), about a foot long.

It is different with us here to what it was in Fort Macon and Newbern, as we are now the same as regulars. We have to come under the general regulations of war. I do not think that we will leave here for some time yet, as the whole regiment has to be uniformed with state dress. We have not received anything, and have only drilled this morning. Capt. Hall, of the Irish Company of Wilmington, in Tew's regiment,

Page 44

had one of his men hung over a pole by the thumbs, but Col. Tew had him taken down. In Tew's regiment there are 200 men sick, and a great many have died already, but in ours there are only two in the hospital. Walter sends his love. When you write, direct Camp Hill, Company F., Fourth Regiment, infantry.

Goodbye.

Your affectionate son,

GEORGE.

RICHMOND, VA., July 22, 1861.

Dear Mother:

We

arrived here yesterday, and had to walk about

four miles to our camps, with our knapsacks on our

backs, and everything necessary to soldiers. Before

we left Camp Hill, we got our state uniform, blankets

and all the accouterments. We were nearly worn out

after having walked four miles to our encampment,

the knapsack straps hurt our shoulders, besides the

weight. We expect to leave here for Manassas to-day,

but I do not think we will, as it is raining.

We are enjoying ourselves finely. I have not had anything to eat since yesterday morning, except some cake and apples. We slept on the ground last night, and I felt sorter chilly this morning, but we will soon get used to that. I must close now. Give my love to all.

Goodbye.

Your affectionate son,

GEORGE.

Page 45

RICHMOND, VA., July 22, 1861.

My Dear Mother:

As George wrote two or three times since I have, I

told him I would write when we got to Richmond.

The first thing I knew this morning was that he was

writing home, so I told him to leave some room for

me and I would write some in his letter.

There is not much to write, as we are about four miles from the center of the city. We don't hear any news, though we heard yesterday that they were fighting at Manassas Gap all day. We heard none of the particulars. Captain rather expects to leave to-day, but I do not think we will. Col. Anderson came along with us. We left half of the regiment at Camp Hill (five companies). My opinion is that we will stay here until the other five companies come, and all of us leave together.

David Carter and little lawyer Marsh are both Captains in our regiment. George got the bundle you sent him yesterday. We are enjoying camp life now to perfection. Heretofore we have had a plank floor, but now we pitch our tents, spread our blankets on the ground and sleep as sound as you please. I never slept better in my life than I did last night. If it stops raining this morning I expect to go up town shopping, and if I have time I want to have myself and George's likeness taken together and send it home, as you may never see either of us again.

I can't tell you anything about Richmond yet, as we have not seen any part of it but one street, that was about four miles long, and led out of town to our camp. We are much obliged for the bed quilts.

Page 46

They do us a great deal of good. We do not trouble ourselves to carry them, but roll them up in our tents. We got blankets before we left our camps. Some of them were the finest I ever saw. I was detailed to give the blankets and knapsacks out, so I kept the best out for all the boys in our tent. They are so fine and nice I hate to spread them on the ground.

Fitzgerald, Henry Warren, Billy Barnes, Tom Stith, George and myself compose the inhabitants of our tent. We have a very respectable crowd. I like it much better than being in a room with the whole company. As we are we have just as nice and quiet a time of it as if we were in a private room.

Give my love to sisters, and believe me, as ever, your sincere and affectionate son,

WALTER.

P. S. I don't know where to tell you to direct your letters in future, as it is uncertain how long we stay here.

COMPANY F., FOURTH REGIMENT, N. C. STATE TROOPS.

NEAR MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., July 31, 1861.

Dear Mother:

This

is the first opportunity I have had of writing

to you since I've been here. We do not live as well

here as we have, but we make out very well. We have

to walk about a mile for our water; as the ground is

too rocky to dig a well we get it out of a spring. You

can't imagine how much I wish to see you all, I long

to be free to go where I please. But alas, there is no

telling where I may be, for when we first came here

Page 47

we did not expect to stay here this long without having a fight. I went over to the battle field last Sunday, and there met a most horrible sight, for it had been over a week after the fight, and the bodies of the men had been blackened by the burning sun and the horses had a most disagreeable smell.

On our going on the field the first object that met our gaze was a grave in which fifteen North Carolinans were buried. We next came to a Yankee who had only a little dust thrown over him. One of his hands was out, which looked very black, the skin peeling off, and you could see the inscission in it. The next which I noticed particularly had his face out and his white teeth looked horrible. The worms were eating the skin off his face. It made me shudder to think that perhaps I may be buried that way.

There are wounded prisoners all through the country in every house. I hope that peace will soon be declared, that we may enjoy the happiness with which we were once blest. I wish you all would write to me for I long to hear from you.

I suppose you heard about Frank T. running from the enemy; it is true, the officers told it. The General gave him his choice to have a Court Martial or be discharged through cowardice, and he took the latter.

We have our little bantams with us yet, and we intend that they shall crow in Washington City, which is only thirty-three miles off, if we live. I must close.

Goodbye,

Your affectionate son,

GEORGE.

Page 48

MANASSAS JUNCTION, August 23, 1861.

My Dear Mother:

We received your letter this morning when John

Clark came. George wrote a day or two ago, which

you had hardly received when you last wrote. There

is no news of any kind worth writing. George and

myself are both well at present. It has been raining

here for nearly a week, and it is tolerably cool. This

morning was very cool and chilly. It begins to feel

like winter is fast approaching. You spoke of

sending us some winter clothing. We would be very

glad to have a good supply, as we shall suffer if not

well clothed in this cold country. I can almost imagine

now how cold it will be on top of these high hills when

the winter winds come whistling around them. The

following list of clothes will be as many as we shall

need and can take care of conveniently. Two pairs

of thick woolen shirts each, such as can be worn either

next to the skin or over other shirts; two pairs of red

flannel drawers each, and some woolen socks, that is

everything that we shall need for the present. You

can send them by express, and we shall get them. You

need not attempt to come to see us, for it will be impossible

for you to get here. Men are not even allowed

to come after their sons to carry them home when they

die with sickness in the service. I tell you this to save

you the trouble and expense of coming so far and

then having to go back without seeing us. It is a

great deal harder to get back after you get here than

it is to come.

Ed Harris is now here with us, he came day before

Page 49

yesterday. He will leave in the morning, and I shall send this letter by him. He got here through the influence of some members of Congress of his acquaintance in Richmond.

Give my love to all. Tell them to write often and let us hear all the news.

Good bye.

Your devoted son,

WALTER.

P. S. Please name my dog Nero and try to make him of some account. What is sister's address?

Dear Mother:

As Walter has told you everything, I shall be at a

loss what to say, but I cannot help writing when an

opportunity presents itself. Our fare is bread and butter

and occasionally a little honey. The two latter

articles we buy. The nights have been rather cool

of late, but we have not suffered any yet.

I wish some of you would write every day, for I do love to hear from home so much. I do not know what else to say, I only thought I would write to let you know that I was still in the land of the living. Write soon, some of you. Tell Dr. Harrell that I shall endeavor to write to him soon. If you have an opportunity, I wish you would send some paper and envelopes, as every letter we send costs about ten cents, and that is too exorbitant a price. Give my love to all. Goodbye.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

Page 50

MANASSAS JUNCTION, October 11, 1861

Dear Mother:

I would have written as soon as I received your

letter if the box had come with it, but as the captain

could not bring them with him, he had to get them

transported on freight, which did not arrive until yesterday.

You never saw such a mess in your life, cakes

molded, meat spoiled, etc. Everything was safe and

sound in our box, which we rejoiced at very much,

for we have not been faring the best for the last

week or two. Tom Stith got a box which was full

of cake and nearly every bit of it was spoiled.

I am thankful for the boots, which are a trifle too large but I reckon by the time that I put on two or three pairs of stockings, they will nearly fit me. We were all very glad to see the captain and we were also pleased to see the things he brought with him, which added so much to our comfort. Times are all very quiet about here. We hear firing on the Potomac nearly every day, though I heard some of the boys say that Mr. Christman was collecting goods to bring to the soldiers. If such be the case I wish you would send me an old quilt or something as somebody has stolen my shawl and I think I shall need one this winter, but you need not send anything unless some one can bring it, for it will cost too much to get anything here. We are all well and if we had been sick our boxes would have cured us. Concerning what Jeff Davis says, I don't think I shall take any notice of it at all, for there are already too many healthy young men skulking around home and I could not bear

Page 51

the disgrace of leaving the army because I was not eighteen years old, but shall stay in the service until the war is over. I must close now, give my love to all and tell them to write.

Goodbye.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., October 24, 1861.

Dear Mother:

I received your letter this morning and was very

glad to hear from you all, but was very sorry to hear

that sister was sick. There were 544 prisoners brought

in here yesterday morning from Leesburg, an account

of which you have seen in the paper ere now. They

were sent off last night to Richmond. Blake and Jack

Robinson was detailed from our company to go as

guard. Leesburg has since been taken by the enemy.

Our forces retreated seven miles. The enemy are

about to flank us and I think that we shall have to

fight soon for I guess it is very galling to them to have

so many of their men taken prisoners. We have had

frost for several nights and it is already beginning to

turn very cold, but we have not suffered any yet. I

wear two pair of socks in my boots and they do very

well, for it keeps the cold wind off my legs.

You were speaking of your hogs being fat. You ought to see these up here, they are so fat that they can hardly get along. The beeves that we have here are the fattest and prettiest I ever saw. They are generally large young cows, nearly twice as large as ours at home. I have often wished that you could

Page 52

have such at home. We have got thick overcoats from the government, with capes reaching below our elbows. They are of great service to us in standing guard. If we had a good dog and was allowed to shoot, we could live on rabbits, for I never saw so many in my life, the woods are full of them. If I only had Leo here now, I could get along very well. I don't want him to be an unruly dog, for he comes of such good breed that I would not like to hear of his being killed.

I should like to be at home in hog killing time, and wish I could see Tasso now, for I know he is a fine looking dog. I hope Walter's puppy will not turn out. I should like to be at home with you on Christmas, but the way affairs are going on now I do not think there is any likelihood of it, as for winter quarters, I do not expect that we will go into any at all, for the enemy pride themselves on standing the cold weather and I expect they will attack us in the dead of winter. We learned from the prisoners that the enemy intended to attack us in two or three days, but let them come when they will. I will insure them a very warm reception. Before this reaches you will have heard of L. Barnes' death and also of Bowden's discharge from the army on account of being a minor, etc. Lafayette's death has cast a deep gloom over the company, for he was a very much beloved member. I will be very glad to get those blankets but I would wait and send them by some one, as they might get lost by themselves. All send their love to you.

Give my love to all. Goodbye.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

Page 53

CAMP PICKINS, MANASSAS, VA., NOV. 2, 1861.

MR. CHAS. W. LEE.

Dear Sir:

Yours of the 29th ult. was received to-day, contents duly noted, and I hasten to reply. I must confess to a feeling of surprise that you desire the discharge of your son, Mr. G. B. Lee, from service, as I was of the opinion that you had fully and determinedly given your consent to his serving in the army of the C. S. during the war. Yet, however much I should regret to see George leave us, as he has been with us so long and has been, though young, a strong, athletic and good soldier, you have my free consent to have him discharged. You will be the proper person to apply to the Government through the War Dept., for the same, where I doubt not, should you still desire him to leave, you can, by presenting the facts, after a while obtain his discharge. It is not in my power to do more than give my consent, which you now have. George expressed some surprise on receiving your letter, and says he don't want to leave. I, of course, do not deem it proper to give him any advice, but simply told him to write you whatever he might think proper, as of course you were the person to advise him, when you could. He has just handed me a letter to enclose to you with this. Whatever course you may pursue I shall willingly acquiesce in. If he is still left in my charge, I shall, as heretofore, advise and correct him and use every effort in my power to secure his happiness and welfare. Hoping to hear from you again and that my answer may be satisfactory, I remain,

Yours most respectfully,

J. S. BARNES.

Page 54

MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., November 2, 1861.

Dear Father:

I received your letter this morning through Captain Barnes and I never was more surprised in my life, to hear that you had applied for my dismissal for, although I should like very much to go home, I do not like the idea of being discharged from the army on account of my age, for in size and strength I consider myself able to stand the campaign, and should I go home, I do not think that it would be entirely right for me to stay there when our coast is in such imminent peril. I compare this war to that of the revolutionary, when our ancestors fought for their liberty, that whoever remained neutral were considered Tories, and I think that when this war is over and peace is declared, those who had no hand in it will be considered in the same light as the Tories of old, and I have too much pride in me to allow others to gain the rights which I will possess, besides it would take two or three months before a discharge could be obtained. It took Mr. Bowden that long to get his son discharged. Captain Barnes is going to write and he will tell you all about it.

I am very well satisfied here. I am treated well, and am permitted every indulgence which the army regulations will permit. All the boys wish me to stay. I am a minor in age, as you say, but I am a man in size and everything else, and fully able to be a soldier. Nothing would afford me greater pleasure than to be of service to you, but the confederacy also needs my services. But if you

Page 55

still insist upon my coming home, you can write again. I expect Bowden pictured to you the darkest side of a soldier's life, but there is enough enjoyment blended with it to make a soldier's life very pleasant. I must close now, so goodbye,

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., December 9, 1861.

Dear Mother:

I received your letter some days since and was very glad to hear from you and would have answered immediately but Walter has gone to Richmond and I thought I would wait until he came back. He went with a detail of men to carry prisoners who were taken by the N. C. Cavalry. He came back day before yesterday and brought us several books to read. Among the prisoners was a deserter from the Federal camp. He was a Baron in Russia and being of an adventurous disposition, he came over to participate in a battle or two and accepted a Lieutenant's commission in the Federal army, but finding, as he said, that there was not a gentleman in the whole army, he deserted, took a horse and came into our camp and has been sent to Richmond for trial. Formerly he had a commission in the Russian army, which he showed to the people.

We are expecting a battle daily. Yesterday we were presented with a battle flag from General Beauregard, consisting of white cloth crossed with blue. This is for us to fight under and also every other regiment has one. The enemy knows our national flag and had

Page 56

already tried to deceive us by hoisting it at their head. Now I guess we will deceive them next time.

Our company has been detached from the regiment for the purpose of taking charge of two batteries which another company has left. We are now relieved of a great deal of duty, for we only have to guard the batteries which take six men a day and that brings us on about once a week, and we drill occasionally. With that exception we have nothing to do, but if the regiment leaves to go into a fight our company goes also, and if the battle rages at this point we will give them a few grapes to eat and also a few shells to hide themselves in and then we will play ball with them for a while.

Walter is still at his old, or rather, new post, and has a great deal to do as the chief clerk is very sick. I hope we shall get a chance to come and see you before the winter is gone, but I have given up the idea of seeing you this Christmas, altogether, but after the fight I reckon we can get a chance to go home. Give my love to all and tell them to write soon.

Goodbye. I remain as ever,

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., January 16, 1862.

Dear Sister:

I received your letter some days since and was very much rejoiced to hear from you, but I thought that you were a very long time in answering my last. It came at last and eagerly did I devour the contents and

Page 57

with what pleasure I lingered on every sentence, no tongue can tell. The description you gave of your tableaux interested me very much, and I regret very much, not being able to have been there, as all such scenes always interest me so much, besides the desire of seeing you act. I think, myself, that you should have had your face painted, and that would have set off the piece a great deal. It is a pretty hard piece. Didn't you feel pretty scared? What does Dick act? Who was that sweetheart of yours that has been home four times? I should like to know him.

We have a hard time of it here now. The ground is covered with snow and then a sleet over that, and it is nearly as cold as the frozen regions, the winds come directly from mountains and blow around us like a regular hurricane. But we have now moved into our winter quarters, huge log hut, and we keep very comfortable, but it is nothing like home, home with its sweet recollections. As I sit and write I cannot refrain from gliding back into the past and enjoying the blessed memories of yore. But enough of indulging the imagination, for this is a sad reality and it will not do for my imagination to assume too large a sway. Tell Miss Myra that when I visit Washington I will call on her parents. I expect to go there soon, either as a visitor or captive, but I hope as the former. We will have a tableau before long, I expect, but I expect the scene will be played in a larger place than a hall. It will encompass several miles and will take several hours to perform it, but when it does come

Page 58

off it will end in a sad havoc. I am very thankful to you for those socks you knit for me, and when I wear them I shall think of you. All around me are asleep and the huge logs have sunk into large livid coals ever and anon emitting large brilliant sparks, that cast a ghastly hue around the whole room, and I now think it time to close, so goodbye.

Your loving brother,

GEORGE.

MANASSAS JUNCTION, February 22, 1862.

Dear Mother:

I did not intend to write before the Captain came back, but as one of our men is going home on a sick furlough I though I would write a few lines to let you know how we are. I expect the Captain is at Richmond at the Inauguration of the President (Jeff Davis), if so he will be here by tomorrow night, and we are all anxiously waiting for his return, each one looking for a letter and a box of good things.

The weather is still very bad and there is an incessant rain since morning, the roads are so sloppy and rough that the wagons can hardly get along over them and very frequently we have our wood to carry on our shoulders to keep our fires burning, but nevertheless we are getting along nicely and not much incommoded from the inclemency of the weather.

To-day you will remember is my birthday, seventeen years old. In size I have been a man for sometime, and now I am nearly one in age. I do not feel as boyish as I did when I left home, for here we have

Page 59

to act the man whether we are or not, and it has been quite natural for me to do so. In the service is a splendid place to study human nature, you can very early find out what a man is. This war will be a benefit to me and an injury to others. Some seem to lose all pride for self, and like a brute are governed entirely by their animal passions. Such persons may be found kneeling at the shrine of Bacchus, to such persons it is decidedly injurious. As for myself, I think it will be very beneficial, for I learn to take care of myself, think and act for myself. I now see how much education is needed, and I regret exceedingly not having applied myself more closely when I had the opportunity. If this war closes within the next year I intend to go to school again, and at the shrine of Minerva seek that which I have never obtained.

One Company of the North Carolina Cavalry were taken prisoners the other day. I do not know which company. Was never in better health. Give love to all.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

You must excuse such a disconnected letter for my mind is very much confused. Love to all, Miss Mollie and everybody.

MANASSAS JUNCTION, VA., March 5, 1862.

Dear Mother:

As I have nothing to do to-day, I thought I would let you all know how we are getting along. The weather is still very bad, ground muddy and miry

Page 60

as it can be. We all have had orders to have our heavy baggage ready to send off at a moment's notice, and also to be ready for the field. The enemy is continually marching upon us, and I expect that we will be in a fight soon, but the enemy cannot do so much damage for they cannot bring their artillery along with them. I was vaccinated last week and my arm is now very sore. I am excused from duty on account of it. I wish you would please get a pair of bootlegs and have them footed for me, a thick double soled pair, that will stand anything, and well put up so that there will be no ripping, and send them by Pat Simms. Ask him to take them along with him or Virgil, and also send what they cost, for I don't reckon that you have the ready cash, and will send the money. Let the boots be No. 8, made so that they will fit him, for I guess our feet are pretty near the same size. If you cannot get a pair made, get a pair out of the store, for I am just almost out and there is none about here.

Tell my sisters I think they could answer my letters. I must close now. Give my love to all.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

Don't get the boots if they cost exceeding $10.00.

March 14, 1862.

Dear Mother:

We are all well as can be expected from the situation that we are now in. We have retreated from Manassas on account of not being able to hold our position. We are now 25 miles from Manassas, across

Page 61

the Rappahannock, and camped upon a high hill that commands a splendid view of that part of the river, which the enemy is compelled to cross.

We left Manassas on Sunday night and traveled until about 1 o'clock. When we camped for the night, everything that we could not carry on our backs was burned up, and I can tell you that you cannot imagine how much we suffered on the march, which consisted of three days' traveling, loaded down with our baggage and equipment, sleeping on the hard, cold ground, feet sore, half fed on hard dry crackers and meat. Our lot was not to be envied, and it is amazing how we bore up under the circumstances. We have been at this place for a day or two, for what purpose I know not, unless it be for us to recruit up for another march. We have no tents here to sleep in, but we have made ourselves shelters out of cedar bushes. We all seem to flourish, nevertheless.

The night we left Manassas it was burnt down and I expect there was a million of goods consumed on that night, all the soldiers' clothes they could not carry with them and everything that could have been expected to be at such a place where everything was sent to this division of the army, all was burnt.

I do not know where to tell you to send your letters, for I do not know how long we will stay here, so I reckon you had better not write at all. When I get to a place where it is likely we will stay, I will write again at a better opportunity.

Give my love to all. Goodbye.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

Page 62

HDQTS. SPECIAL BRIGADE, NEAR RAPIDAN

STATION, VA., March 23rd, 1862.

My Dear Mother:

We received your letter last night dated the 6th of March. 'Tis the first time any of us have heard from home within the last two weeks. We have had considerable excitement since you last heard from us. To-day, two weeks ago, we evacuated Manassas and have been moving to the rear ever since. We are now on the South side of the Rapidan River, where I think we will make a stand. But nothing is known for certain, I don't believe the Generals themselves know. The night we left Manassas (about sunset) we marched ten miles that night, stopped about two o'clock and slept on the ground with the sky for a covering. We haven't had a tent in two weeks. We are playing the soldier now in good earnest. The last three days we marched it rained every night just as soon as we would stop for the night. After walking all day, carrying your ALL on your back, then having to start a fire out doors without wood (we have no light wood) and cook your next day's ration, is pretty hard soldiering, I can assure you. Though the boys all seem to be cheerful. We have very little sickness and for the last ten days (a circumstance not known before since we have been in Virginia) we haven't had a man to die in the Regiment. Pat Simms and his recruits have not yet arrived, they were stopped at Gordonsville some time ago, while we were making our retreat from Manassas. We expect them daily.

The Yankees have been some distance this side of

Page 63

Manassas. Our troupes had a little skirmish with them a day or two after we left, some of the Cavalry came in sight of our pickets. They fired on them and they disappeared, 'tis reported that they have gone back to Centerville, perfectly non-plussed at our movement. The country we are now occupying is the prettiest and the most beautiful scenery you ever saw. We can see the mountains in the distance covered with snow, and when the sun shines it is sublime. We are on what is called the "Clark Mountain." There is a mountain or rather hill, on a mountain, about a quarter of a mile off that commands a view of the country for miles around, some of the men are up there all the time. I intend to send this letter to Richmond to be mailed. I do not know that there is any communication between here and Richmond. We only got the old mail that was stopped at Gordonville . MacWilliams, one of our company, is going to Richmond tomorrow on business. I will get him to mail it for me.

I do not see a word about this move in the papers, so I must think the Government is withholding it from them, to prevent the Yankees from obtaining information. Johnnie Dunham is still A. A. Genl. of the Brigade and I am writing for him, though I do not have one third to do that I did at Manassas, as that was a regular military post. We had inspection to-day, to see how the guns, etc., were getting on after the hard usage and bad weather they have gone through lately.

Write soon. We may get all of your letters, though you might not get all of ours, unless mailed beyond

Page 64

Gordonsville. Give my love to all the family, Aunt and Claudia, etc. etc. I remain,

Your sincere and devoted son,

WALTER.

March 23rd, 1862.

Dear Mother:

As Walter did not mention me in his letter, I thought I would let you know that I am well. Walter has told you nearly everything that transpired on our tramp, so I have not anything to tell except the burning of the property at Manassas the same day that we left. We had been told to go to the Junction and get what things out of our boxes as we could carry on our backs, for the boxes would not be carried on the train. After we left, the town was set on fire, and I expect that a million dollars' worth of property was consumed. We had to leave our little Bantam chickens, as we had no way to carry them. The first night of our march, I never suffered so much from fatigue in my life. When we did halt we fell on the ground and slept soundly until next morning. I do not expect you can hardly read this, as it is done by a log fire on my cartridge box. Must close. Good bye.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

YORKTOWN, VA., April 13, 1862.

Dear Mother:

I commenced a letter to you the other day but was unable to finish it, being called off to participate in a

Page 65

slight skirmish with the Yankees. We arrived at this place last Thursday evening and having sent out our portion of the picket, of which I was one, we ate our hard bread and meat and laid on the hard, cold ground for the night, with the blankets we brought on our backs for a covering. On Friday we were ordered out, for the Yankees were about to attack us, our skirmishers went out towards the enemy for the purpose of drawing them within range of our batteries, the enemy came in sight with a long line of artillery and drew up in battle array about half a mile from our batteries, by that time there was some right hard fighting on the part of the skirmishers. About two o'clock p.m., our batteries opened upon them and they were returned with the greatest alacrity; bombs, shells and balls flew about promiscuously, but happily they did no damage on our side, nearly all of them going over our heads. We threw some shells that seemed to do damage with the Yankees, the way they scattered when the shell fell among them. One shell which came over us bursted and fell all around, one piece fell right between two of our boys, but no injury done. The firing continued until dark, in the time the skirmishers set fire to a large dwelling house, near the enemy's infantry and under the cover of the smoke they broke in on them and routed them, but they had soon to retreat for the Yanks turned their batteries upon them, after which hostilities ceased for the night. We lay in the entrenchments all night. Next morning, Saturday, the enemy was not to be seen. This morning we are expecting an attack again, and have been

Page 66

ordered into the entrenchments, but they have not made an attack yet.

Gen. Magruder says that if they do not attack us to-day, that he will them to-morrow. We are exactly on the battle ground of Washington and Cornwallis, but all that remains to be seen are the old breastworks of the British, which lie immediately behind ours. The Yankees hold the same position that Washington did. There is also the place where Cornwallis surrendered his sword to Washington. Yorktown is the oldest place I ever saw. I do not believe that there is a single house that has been built in fifty years. As I was walking through the town, I chanced to come upon an old grave yard, that had gone into entire ruin. There could be seen the tombstone of the Revolutionary soldier, citizen and foreigner. The oldest one was dated 1727, that was the tombstone of an old lady sixty years old, and another of a president of his majesty's council in Virginia. He died in 1753, and all the rest of nearly the same date. It was a perfect pleasure to me to look over the old place, such a contrast to the clay hills of Manassas. I feel nearer home, but still I am a long ways off. I am wanted now, as they are continually detailing men for something or other. I will send the letter I wrote the other day. When the battle closes I will write again.

Give my love to all.

Your loving son,

GEORGE.

P. S. I have not heard from Walter yet, except from a man that came from the hospital, he says that his hand is nearly well.

Page 67

RICHMOND, VA., June 15, 1862.

Dear Mother:

I hope you are not uneasy about me because I have not written before. I knew if I wrote it would take a week for you to get it, so I put it off till I could send it by Mr. Albert Farmer, who will go tomorrow. The Surgeon of the hospital has given me a passport to stay wherever I please in the city and report to him every week. I believe I should go crazy if I had to stay out in the hospital where everything is so dull and disheartening. In fact I don't believe I am the same being I was two weeks ago, at least I don't think as I used to and things don't seem as they did. I don't believe I will ever get over the death of George. The more I think of him the more it affects me, and unless I am in some battle and excitement I am eternally thinking of the last moments of his life. How he must have suffered, if he was conscious of it. I shall never forget it. I think a long letter from some of you would make me feel so much better. I shall send by Mr. Farmer my watch, sleeve buttons, also the shirt I wore off. Everything I ought to have left at home I brought away and a great many things I ought to have brought I left behind. I only brought one flannel shirt, and by the way I'll send this one back and try this summer without them, as they are very heavy for summer wear. The war news you read every day in the papers, but Capt. Billy Brown came down from Gordonville with some of Jackson's prisoners. He says he was in Lynchburg. Twenty-two hundred were sent in and that thirteen hundred were on the way.

Page 68

The Yankees that are near Richmond, we don't hear anything of, everything is quiet. Please some of you write me soon.

Your loving son,

WALTER.

HEAD QUARTERS, ANDERSON BRIGADE,

RIPLEY DIVISION, August 11, 1862.

My Dear Mother:

I am sorry I have kept you waiting so long before writing to you, but I thought I would wait until I could have a talk with General Anderson to find out what I was to do before writing. I sent word by John Hines, also Dr. Barham, that I was well and for them to tell you all the news. When I arrived at the Camp of our Regiment it was gone to Malvern Hill to have a fight with the Yankees. They did not return in a day or two. General Anderson went to Richmond immediately on business, so I did not have an opportunity of speaking with him until this morning. He was perfectly willing for me to come back into the office, so I commenced duty this morning. We have a very pleasant place for our quarters, a large two story house with plenty of shade, in an open field, where we have the breezes from every direction.

I don't know yet, but I may come up here to mess and sleep, though I thought I would wait a while. I haven't slept in a tent since I've been in camp, but once. That was last night. It rained yesterday morning, and the ground was wet, and the air rather cold, so I thought I would go in the tent, as it was

Page 69

convenient. I shall go in bathing tonight to cool off, and sleep out doors. We have an excellent place for that purpose, that is bathing. It's been awfully hot here today. I believe it is warmer here than at home.