With Sabre and Scalpel. The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon:

Electronic Edition.

Wyeth, John Allan, 1845-1922

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Tricia Walker

Images scanned by

Tricia Walker

Text encoded by

Heather Bumbalough and Natalia Smith

First edition,

1998

ca. 1MB

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number E605.W97 1914 (Davis Library, UNC-Chapel Hill)

Source Description:

(title page) With Sabre and Scalpel. The Autobiography of a Soldier and Surgeon

Wyeth, John Allan

New York, NY

Harper & Brothers Publishers

1914

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-Chapel Hill

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and '

respectively.

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor

(SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- Latin

- Italian

- German

- French

- Spanish

LC Subject Headings:

- Wyeth, John A. (John Allan), 1845-1922.

- Alabama -- Social life and customs.

- Confederate States of America. Army. Morgan's Cavalry Division.

- Confederate States of America. Army. Alabama Cavalry, 4th. Company I.

- Camp Morton (Ind.)

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Prisoners and prisons.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Hospitals.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- Soldiers -- United States -- Biography.

- Surgeons -- United States -- Biography.

- Medicine -- Study and teaching -- United States.

- Surgery -- Study and teaching -- United States.

- Wyeth family.

Revision History:

- 1999-01-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-12-18,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-12-17,

Heather Bumbalough

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-11-22,

Patricia Walker

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

WITH SABRE AND SCALPEL

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

A SOLDIER AND SURGEON

JOHN ALLAN WYETH, M.D., LL.D.

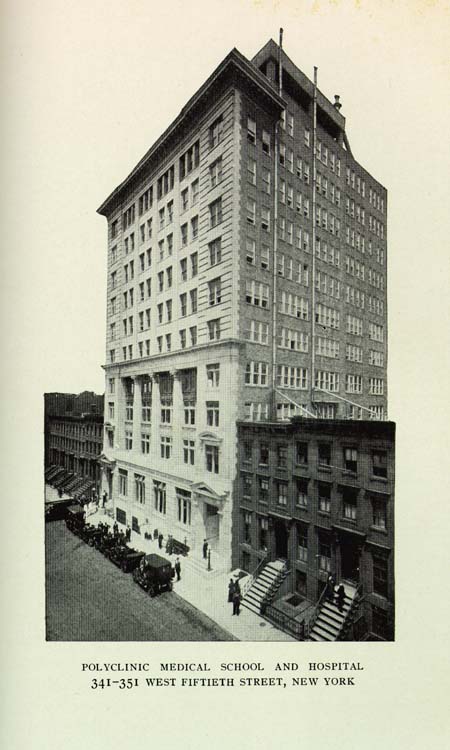

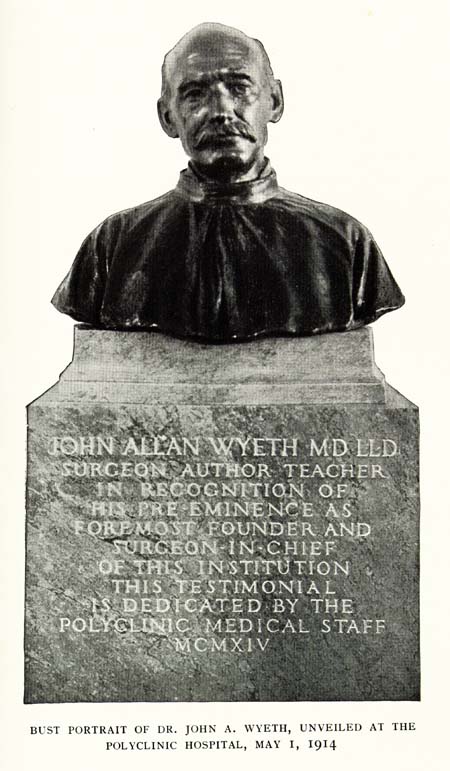

UNIVERSITIES OF ALABAMA AND MARYLAND

FOUNDER OF THE NEW YORK POLYCLINIC MEDICAL SCHOOL AND HOSPITAL, THE PIONEER ORGANIZATION FOR POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL INSTRUCTION IN AMERICA--PRESIDENT OF THE FACULTY AND SURGEON-IN-CHIEF; EX-PRESIDENT OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MEDICINE, THE NEW YORK STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, THE NEW YORK PATHOLOGICAL SOCIETY, THE NEW YORK SOUTHERN SOCIETY, AND THE ALABAMA SOCIETY OF NEW YORK CITY; FORMERLY ATTENDING SURGEON TO MT. SINAI AND ST. ELIZABETH HOSPITALS; HONORARY MEMBER OF THE MEDICAL SOCIETY OF NEW JERSEY AND OF THE TEXAS STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION; AUTHOR OF ESSAYS IN SURGICAL ANATOMY AND SURGERY; AWARDED THE FIRST AND SECOND PRIZES OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION IN 1878 AND THE BELLEVUE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION PRIZE IN 1876; A TEXT-BOOK ON GENERAL SURGERY; THE LIFE OF LIEUTENANT-GENERAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST; HISTORY OF LA GRANGE MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE CADET CORPS; A HISTORICAL ESSAY ON THE STRUGGLE FOR OREGON, ETC.

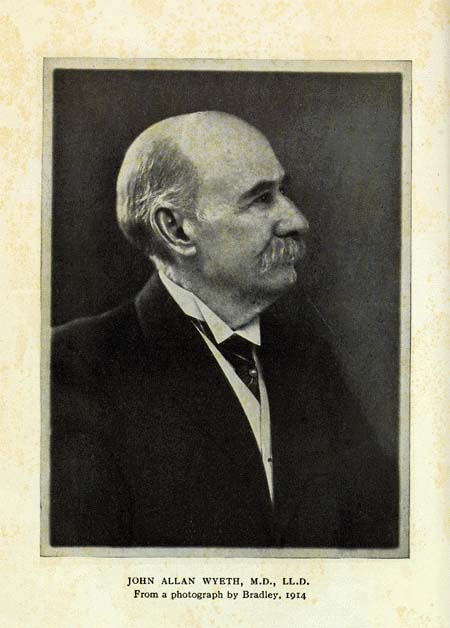

JOHN ALLAN WYETH, M.D., LL.D.

From a photograph by Bradley, 1914

[Frontispiece Image]

[Title Page Image]

WITH SABRE

AND SCALPEL

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF A SOLDIER AND SURGEON

BY

JOHN ALLAN WYETH

M.D., LL.D.

ILLUSTRATED

HARPER& BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

MCMXIV

Page verso

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY HARPER& BROTHERS

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PUBLISHED OCTOBER, 1914

K-O

Page v

TO

LOUIS WEISS WYETH

AND

EUPHEMIA ALLAN

"MY BOAST IS NOT THAT I DEDUCE MY BIRTH

FROM LOINS ENTHRONED AND RULERS OF THE EARTH;

BUT HIGHER STILL MY PROUD PRETENSIONS RISE,

THE SON OF PARENTS PASSED INTO THE SKIES."

COWPER

Page vii

CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION . . . . .xiii

- I. THE TENNESSEE VALLEY--MARSHALL COUNTY AND GUNTERSVILLE IN ALABAMA . . . . .1

- II. EARLY RECOLLECTIONS . . . . .5

- III. OUR VILLAGE BOYS . . . . .10

- IV. HORSE AND GUN . . . . .14

- V. MAJOR, THE VILLAGE KING--LESSON FROM THE LIFE OF A NOBLE DOG . . . . .23

- VI. EARLY SCENES, RELIGIOUS AND OTHERWISE . . . . .30

- VII. THE ARISTOCRACY OF THE OLD SOUTH . . . . .37

- VIII. THE NEGRO AND SLAVERY IN THE OLD SOUTH . . . . .52

- IX. THE POINT OF VIEW--HISTORY OF AMERICAN SLAVERY AND THE ABOLITION CRUSADERS--SOME TRUTHS ABOUT JOHN BROWN AND THE SO-CALLED MARTYRDOM . . . . .74

- X. SOME FACTS ABOUT JOHN BROWN NOT GENERALLY KNOWN . . . . .94

- XI. A DISSERTATION UPON THE PERVERSION OF FACTS--SKETCHES FROM THE BACKWOODS OF ALABAMA--THE GRAPE-VINE TELEGRAPH--THE LIARS' TOURNAMENT--THE SHERIFF'S STORY OF "WHEN THE YANKEES FIRST CAME" . . . . . 128

- XII. THE SNAKES OF NORTHERN ALABAMA . . . . . 147

- XIII. MY YEAR AT COLLEGE--THE GUNBOAT INCIDENT . . . . . 160

- XIV. WITH MORGAN'S CAVALRY--THE CHRISTMAS RAID--1862-1863 . . . . . 177

- XV. FOURTH ALABAMA CAVALRY . . . . . 197

- XVI. COVERING THE RETREAT FROM TULLAHOMA--THE 27TH OF

JUNE, 1863 . . . . .210

Page viii - XVII. TULLAHOMA TO ALEXANDRIA--ELK RIVER . . . . . 223

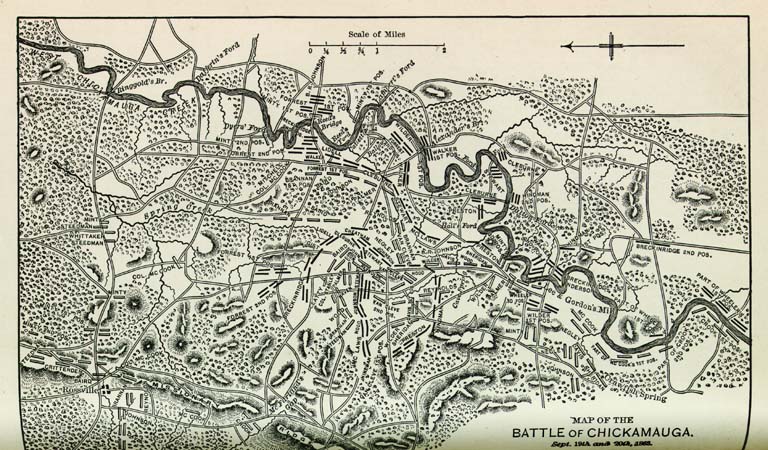

- XVIII. CHICKAMAUGA, WHERE THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY WAS WON AND LOST--THE REAL CRISIS OF THE CIVIL WAR . . . . .237

- XIX. SEQUATCHIE VALLEY--CAPTURE OF THE GREAT WAGON-TRAIN --A PRISONER OF WAR . . . . .265

- XX. PRISON LIFE IN CAMP MORTON--HOMEWARD BOUND--JOHN JONES . . . . .286

- XXI. AFTER THE WAR . . . . .313

- XXII. A MEDICAL STUDENT IN 1867--THREE YEARS IN ARKANSAS --STEAMBOATING AND CONTRACTING . . . . . . . . 327

- XXIII. AT BELLEVUE MEDICAL COLLEGE--WORK IN THE DISSECTING-ROOM--ASSISTANT DEMONSTRATOR AND PROSECTOR TO THE CHAIR OF ANATOMY--BEGINNING OF THE PRIZE ESSAYS IN SURGICAL ANATOMY AND SURGERY--THE STUDY OF GREEK, GERMAN, AND FRENCH--1872-1878 . . . . . 347

- XXIV. LONDON--PARIS--BERLIN--VIENNA--DR. J. MARION SIMS-- MT. SINAI HOSPITAL--TEXT-BOOK ON SURGERY--PRESIDENT NEW YORK PATHOLOGICAL SOCIETY--BLOODLESS AMPUTATION OF THE SHOULDER AND HIP JOINTS--VICE-PRESIDENT AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION--LIFE OF FORREST . . . . .366

- XXV. THE TENNESSEE & COOSA--HOW I FINANCED A RAILROAD AND SAVED A FORTUNE FOR A FRIEND--REVISIT MY ALMA MATER--WRITE THE LIFE OF FORREST . . . . .38I

- XXVI. THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION--THE MEDICAL SOCIETY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK--THE NEW YORK STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION . . . . .395

- XXVII. ITALY AND THE GREAT ST. BERNARD--THE BONAPARTE TRAIL--MARENGO . . . . .399

- XXVIII. MIND-READING OR THOUGHT-TRANSFERENCE--THE VALUE OF SUGGESTION--CHRISTIAN SCIENCE--THE MIRACLE SAT LOURDES--A MORMON EPISODE AND OTHER EXPERIENCES . . . . .414

- XXIX. RIGHT HANDEDNESS OR DEXTRAL PREFERENCE IN MAN--

ALSO SOME SUGGESTIONS AS TO THE VALUE OF ENFORCED

AMBIDEXTERITY . . . . .432

Page ix - XXX. OCCUPATIONS OF A RETIRED LIFE--BUILDING THE NEW POLYCLINIC HOSPITAL--PRESIDENT OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MEDICINE AND OF THE NEW YORK SOUTHERN SOCIETY--CHAIRMAN OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE UNION LEAGUE CLUB, ETC. . . . . .444

PART I

- I. FOUNDING THE POLYCLINIC . . . . .461

- II. LIGATION OF THE EXTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY . . . . .467

- III. BLOODLESS AMPUTATION AT THE HIP--JOINT AND AT THE SHOULDER . . . . .472

- IV. THE TREATMENT OF VASCULAR TUMORS (ANGIOMATA) BY THE INJECTION INTO THEIR SUBSTANCE OF WATER AT A HIGH TEMPERATURE . . . . .480

- V. DEMONSTRATION BY EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES ON ANIMALS AND BY OPERATIONS ON HUMAN BEINGS OF THE PROCESS OF PERMANENT ARTERIAL OCCLUSION AFTER DELIGATION . . . . .486

- VI. CONTRIBUTION TO THE STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF STREPTOCOCCUS AND PYOGENIC INFECTION UPON SARCOMA . . . . .489

- VII. THE SURGICAL ANATOMY AND SURGERY OF THE TIBIO-TARSAL ARTICULATION, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO A MODIFICATION OF SYME'S AMPUTATION . . . . .495

- VIII. TRANSPLANTING SKIN FROM THE ABDOMEN OR OTHER PARTS OF THE BODY TO THE HAND OR FOREARM--TRANSFERRING THE GRAFT BY THIS MEANS TO THE FACE, NECK, OR ELSEWHERE . . . . .498

- IX. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SURGERY OF THE MOUTH, NASOPHARYNX, AND ANTRUM MAXILLARIS . . . . .502

- X. CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SURGERY OF THE BONES-- TRANSPLANTATION OF THE PROXIMAL END OF THE ULNA TO THE DISTAL OF THE RADIUS IN AN UNUNITED COLLES' FRACTURE. . . . . .509

- XI. HIP-JOINT DISEASE TREATED BY COMBINATION OF HUTCHINSON'S HIGH SHOE AND CRUTCHES AND SAYRE'S LONG EXTENSION SPLINT . . . . .514

- XII. VERSES . . . . .520

- GENEALOGY . . . . .528

PART II

Page xi

- JOHN ALLAN WYETH, M.D., LL.D. . . . . .Frontispiece

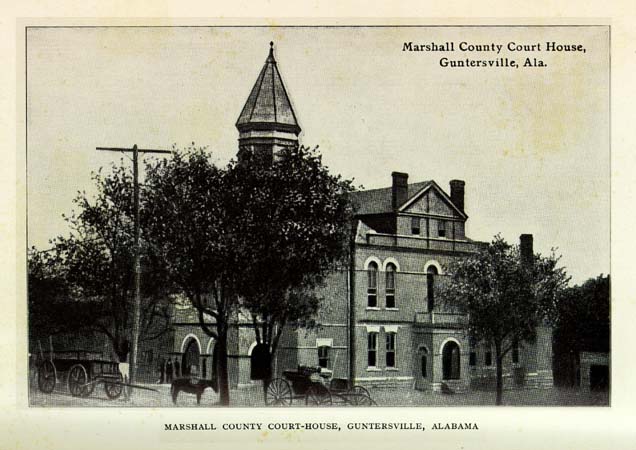

- MARSHALL COUNTY COURT-HOUSE, GUNTERSVILLE, ALABAMA . . . . .Facing p. 2

- CHEROKEE MISSIONARY STATION, 1820 . . . . .Facing p. 8

- "MAJOR" AND HIS PUPIL . . . . .Facing p. 24

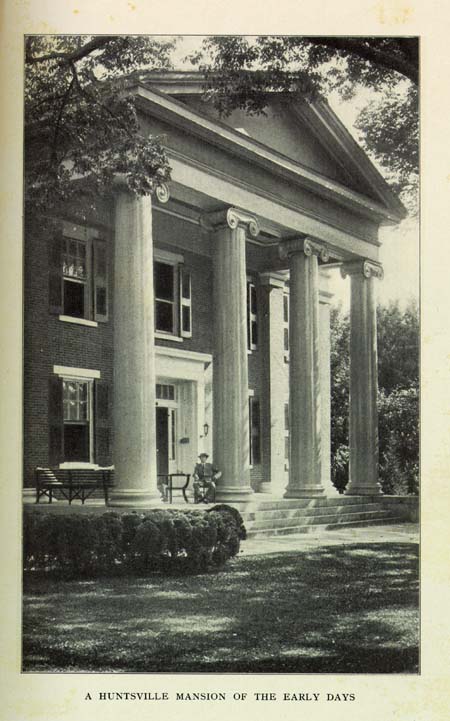

- A HUNTSVILLE MANSION OF THE EARLY DAYS . . . . .Facing p. 48

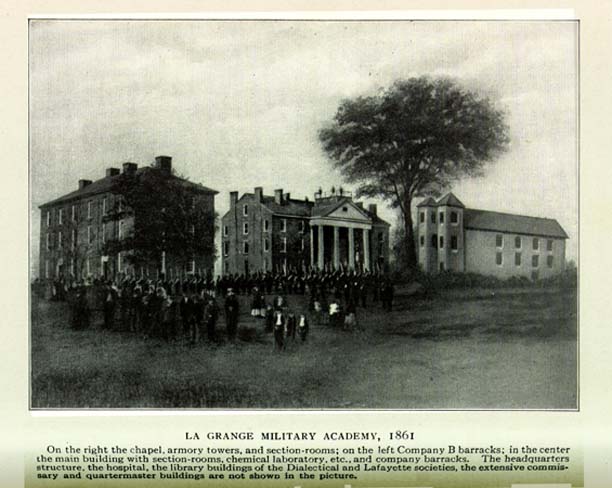

- LA GRANGE MILITARY ACADEMY, 1861 . . . . .Facing p. 160

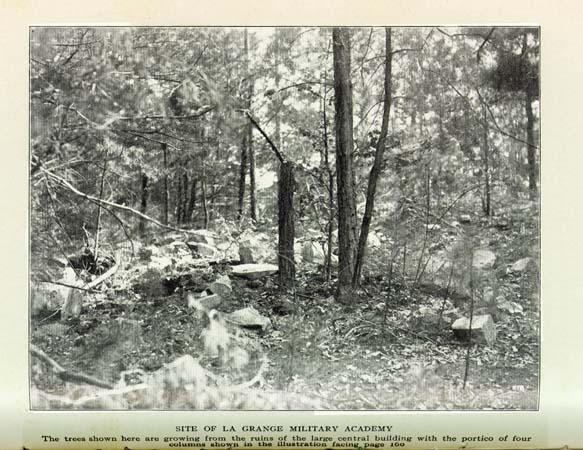

- SITE OF LA GRANGE MILITARY ACADEMY . . . . .Facing p. 164

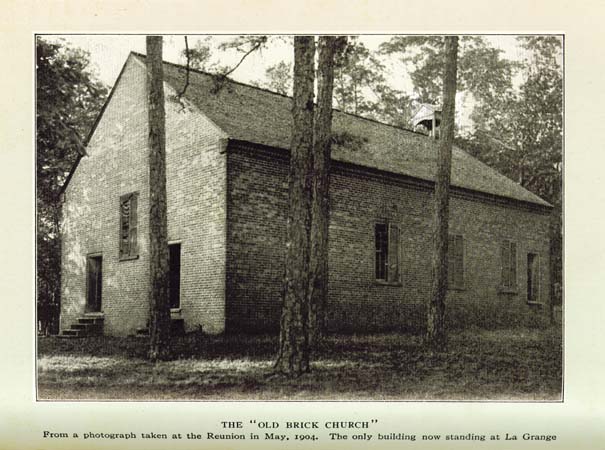

- THE "OLD BRICK CHURCH" . . . . .Facing p. 166

- JOHN A. WYETH, Co. I, 4TH ALABAMA CAVALRY . . . . .Facing p. 212

- LIEUT. JOHN A. GIBSON, Co. C, 4TH ALABAMA CAVALRY . . . . .Facing p. 214

- MAP OF THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA . . . . .Facing p. 239

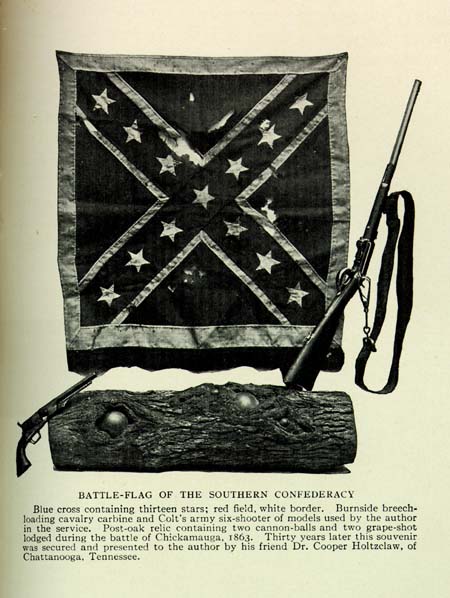

- BATTLE-FLAG OF THE SOUTHERN CONFEDERACY . . . . .Facing p. 262

- STATUE OF DR. J. MARION SIMS, BRYANT PARK, NEW YORK . . . . .Facing p. 370

- A CHAMOIS ON GUARD . . . . .Facing p. 402

- POLYCLINIC MEDICAL SCHOOL AND HOSPITAL, 341-351 WEST FIFTIETH STREET, NEW YORK . . . . .Facing p. 462

- BUST PORTRAIT OF DR. JOHN A. WYETH, UNVEILED AT THE POLYCLINIC HOSPITAL, MAY 1, 1914 . . . . .Facing p. 464

- MY SWEETHEART'S FACE . . . . .Facing p. 520

ILLUSTRATIONS

Page xiii

INTRODUCTION

THE chief purpose of this volume is to record from personal observation something of the social, economic, and political conditions which prevailed in the South before, during, and immediately after the Civil War. It was my good fortune to have been born and reared in a section where the wealthy landed proprietors and slave-owners, the poorer whites, and the negroes came together.

What is written of the delightful society of the aristocracy of the old South at Huntsville would apply to hundreds of other communities of that period below "the Line." It was only possible with the institution of slavery, and with the downfall of the Southern oligarchy it disappeared, never to be repeated. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Marshall, Wythe, Monroe, Mason, the Randolphs and Lees were among the products of that unique civilization. "There were giants in those days."

In my native county the poor whites greatly outnumbered the rich slaveholders and their slaves. The negroes baptized them contemptuously as "poor white trash." They were poor, comparatively speaking, but they were not trash. The vast majority were uneducated, many could not read or write; but they were as a class far from being ignorant, for they were "good listeners" and close observers of current events. My father, whom they made at first county and later district judge, was idolized by these simple people,

Page xiv

and I fell heir to their affectionate guardianship. By the time I was fifteen years old I believe I was personally acquainted with every one of these families in our county. Their homes were chiefly in the uplands or foot-hills or coves or in the sparsely settled plateau of Sand Mountain. The houses were of logs, some hewn, many of skinned poles, and some so primitive that the bark was left on. The roofs were of rived boards, not nailed, but held in place by split logs laid on as weights and reinforced here and there by stones. Some of the floors were of puncheons, others of planks; and not infrequently the kitchen, smokehouse, and other added shelters had for flooring the sandy earth. As might be inferred, their lives were simple, and in general they were obedient to law. They were, however, high-strung and quick to resent an affront, and their too ready appeal to the rifle and the hunting-knife in the settlement of personal differences was the chief exception to their common acceptance of the authority which the court-house represented. Very rarely, far back in some remote fastness, an occasional mountaineer, who gathered inspiration from the sun which curved over his head each day without seeming to pay much attention to human regulations, or from the free air which the preacher told him "bloweth where it listeth," would conclude that the government at Washington had no right to prescribe in what form the corn which he raised with his own hands and on his own land should ultimately be marketed, and would proceed to distil it into whisky by the light of the moon. I shall never forget the feeling which was evident as one of these mountaineers remarked to me: "Your pap put me in jail once for moonshinin', but I never blamed him fer it. We all knowed he was a good man and done what he thought was

Page xv

right." These poor whites were in the main religious, belonging to the Baptist or Methodist persuasions, and were much given to "protracted meetings," revivals, and exhortations to secure conversions, which latter was defined as "comin' through."

They dressed with extreme simplicity, usually in cotton or woolen stuffs, raised, spun, woven, and tailored at home. The mild climate made it possible to go for at least nine months without shoes, and the one pair of brogans for the year was usually put on at Christmas. The young children and boys to about the sixteenth year wore in summertime nothing but a single garment made like a long shirt, which came down to near the ankles and was slit on each side as high as the knees to allow freedom in walking or running. As they raised everything they ate, except sugar and coffee, it may well be said that their wants were few and easily supplied.

At least three-fourths of the men who carried guns in the

battle-line of the Southern Confederacy were of this class.

They had no interest directly or indirectly in slavery, and

would willingly have seen the negroes freed and colonized

out of the country. The proportion of non-slave-owners

in my own company and regiment was greater than seventy-five

per cent. Colonel James Cooper Nesbit,1 in his most

interesting and instructive narrative, says: "My company,

H, Twenty-first Georgia regiment, was recruited in northwest

Georgia and Alabama. The muster-rolls show one

hundred and eighty-five names. All were non-slaveholders

except myself. The parents of four owned one or two

slaves, and the father of one of my lieutenants owned forty.

1 Four Years on the Firing Line, p. 69. Imperial Press, Chattanooga,

Tenn., 1914.

Page xvi

This was the average of the Twenty-first Georgia and the Twenty-first North Carolina of the same brigade, and these two regiments made the best record of any in Stonewall Jackson's corps."

The brave fight these men made was not for slavery. Their contention was that freemen had the inherent right to do as they pleased, and as freemen they would stay in the Union or secede, as the majority desired. They were then and are still clean-cut Americans, uncontaminated by contact or association with the restless, poverty-stricken, and discontented hordes of immigrants who are crowding our shores in these latter days either as anarchists, who, like shedding snakes, strike blindly and viciously at everything which moves, or like the socialists, whose aim is seemingly to bring all human endeavor to the common level of mediocrity. Should the safety of our institutions ever be endangered I prophesy that these men of the foot-hills and mountains of the South will be the strongest guarantee of law and order.

At various periods in history (and doubtless before the records were preserved, for in his natural tendency to do foolish things on a large scale man is the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever) epidemics of insanity have appeared with results more unfortunate to moral and intellectual development than have followed the wide-spread infections of the body.

The legend of the Tower of Babel; the numerous racial migrations; the crusades and the war of the five great nations now in progress in Europe, each of which, claiming to represent a Christian civilization, is calling for divine assistance in robbing and killing, are examples.

One such epidemic has visited our shores. In the agitation

Page xvii

for and against slavery in the United States, reason and conscience were finally dominated by fanaticism. There was a period in the decade from 1830 when by the judicious co-operation of the advocates of emancipation North and South a humane and practical solution of this momentous problem was possible. I ask attention to the fact that at this time there were in the eight largely agricultural and slave-owning counties of my native section along the Tennessee River in Alabama eight active emancipation societies organized by Southern men, and that in Huntsville a former slaveholder edited an emancipation newspaper and was twice nominated for the Presidency of the United States on the abolition ticket; also to the fact that a single state freed negroes approximating in value one hundred million dollars without one penny of remuneration!

I am firmly convinced that if instead of the nagging, irritating, insulting, and finally insurrectionary and murderous meddlesomeness of the Northern abolitionists, the conservative and better portion had united in earnest and friendly co-operation with their brothers of the South, who proved their zeal and devotion to principle by the wholesale sacrifice of wealth and ease, the humane scheme of emancipation and colonization as set forth in the "Virginia Resolutions" would have been carried out and chattel slavery would have disappeared by peaceful means.

That portion of the volume which relates to the Civil War is chiefly a narrative of the every-day life of a private soldier in camp, in battle, and in prison. A single experience-- namely, the battle of Chickamauga--is discussed from the standpoint of speculation. In my opinion the Southern Confederacy was won here by desperate valor and lost by the failure of the commanding general to appreciate the

Page xviii

magnitude of his victory and to take advantage of the great opportunity which was his for the capture or destruction of the entire Union army in Georgia and Tennessee. Chickamauga, as I interpret it from personal observation and from careful study, marked the high tide of the Confederacy.

I have been asked to describe the sensations or emotions which are experienced under the trying ordeal of battle. The courage, whether moral or physical, or the combination of both, which enables a human being to incur the risk of suffering and death is a common possession. I would guess that of every one hundred men in our regiment fully ninety-five would have done, or would have tried to do, more or less willingly, any duty required. The other five would shirk and exhaust ingenuity to keep out of gunshot range by feigning illness, or some temporary necessity, or lagging until a chance offered to dodge behind an obstacle whence only the file-closers could drive them to the firing-line.

In very rare instances the sense of fear became so overwhelming the victim would run away without regard to the commands to halt and the danger of being shot in the back by one's own men.

Personally I never saw any one do this, but it did occur. The very unusual experience of the soldier who, when what was thought to be a dangerous charge was ordered and we were in the act of moving forward, stepped from the ranks and handed his gun to our captain and said he couldn't "go in" is given in the text. Vanity, another name for which is "family pride," or the dread of being called a coward, will account in part for what is usually accepted as courage; and yet admitting all this as a measure of human frailty, I have witnessed a great many instances of that

Page xix

sublime quality of self-forgetfulness in the performance of duty which is the crystallization of virtue namely, true courage. Appreciating, as every normal human being must, the instinctive dread of suffering and the love of life, it is not difficult to realize the awful sensation which is experienced in the moments given for reflection as one marches calmly up to the point of danger. It must, as I take it, count as a supreme moment in existence. Once engaged and in the excitement of fighting, this sense of impending disaster is happily lost; and to some there comes an exhilaration which it would be almost permissible to term ecstatic.

In my own case, in the first two or three minor engagements I was not scared; in fact, the excitement or exhilaration was rather enjoyable; but this was "the valor of ignorance." After I had learned what war really was I never went under fire without experiencing an overpowering sense of dread and fear, with the single exception of the incident of riding through the Union lines at Chickamauga, which is given further on.

Part II is devoted mainly to my work as a surgeon and teacher. My aim has been to collect in concise form for convenient reference those original contributions which have been generally accepted by the profession.

The Ligation of the External Carotid Artery as an accepted procedure dates from the publication of my essays on the arteries by the American Medical Association in I878; the Bloodless Amputations at the Hip-joint and at the Shoulder, in 1889; The Cure of Otherwise Inoperable Vascular Tumors by the Injection into their Substance of Water at a High Temperature; The Immunizing Effect upon Sarcoma of a Mixed (Pyogenic) Infection; The Demonstration of the Process of Arterial Occlusion after Ligation in Continuity, etc.

Page xx

Upon these, together with the introduction of systematized postgraduate medical teaching in America, the author "rests his case" at the bar of posterity. That the Polyclinic gave an impetus to and was coincident with the great awakening in American medicine there can be no doubt. Once inaugurated, the movement practically compelled postgraduate study in the general profession, for it naturally followed, that when even a single practitioner in any community took advantage of the extraordinary facilities which were offered for increasing his store of knowledge, public opinion, that insistent vis a tergo of human progress, compelled the others to follow. Not only has every city of importance in our own country established one or more postgraduate medical schools, but abroad (as in London) our system has been adopted.

Page xxi

PART I

Page 1

WITH SABRE AND SCALPEL

I

THE TENNESSEE VALLEY--MARSHALL COUNTY AND GUNTERSVILLE IN

ALABAMA

FIFTH in size of the rivers in the United States, the Tennessee, rising in the mountainous regions of Virginia and North Carolina, flows in a general direction southwest until, at the great bend in northern Alabama, it turns northwest to empty into the Ohio. Although three-fourths of its course is within the boundaries of the state to which it gave its name, that section of the South widely known as the Tennessee Valley is wholly within the state of Alabama.

Eastward and to the north, from where Lookout stands sentinel for the mighty Appalachian range, the numerous large tributaries fairly divide honors with the main stream, while to the west, after pitching over the great cascade at Mussel Shoals, it leaves the mountains and the picturesque valley through which it has flowed for two hundred miles.

Emerging near Chattanooga from the narrow gorge through which it has worn its way, walled in by cliffs of stone so steep and high that from the channel their crests are at times not within the range of vision, this majestic river enters the beautiful Valley of the Tennessee.

Winding in and out among the mountains on either hand,

Page 2

some near, some far, for most of the year covered with verdure to the steep cliffs which form their crests, opening here and there into fertile plains or densely timbered coves that rise as they recede to reach the summit of the distant heights, on past bold projecting bluffs which seem to block the way, wide fields of corn and grain and cotton which long before the frosts of winter fall shall be as white as snow upon the arctic plains, flows ever on this gracious gift of nature, blessing with plenty my native Valley of the Tennessee.

In 1802 the territory now included in the states of Mississippi and Alabama was ceded by Georgia to the United States, and in 1819 Alabama was admitted to the Union. That portion of this new state lying north of the river had been opened for settlement a number of years, while to the south stretched the reservations of three great Indian tribes--the Seminoles, nearest the Gulf of Mexico; then the restless, warring Creeks, and, closest in touch with civilization, the wonderful Cherokees. Lovers of peace and tactful, they were on living terms not only with their war-like brothers, but friendly also with their Anglo-Saxon neighbors just across the Tennessee. Builders of houses and tillers of the soil, these Indians had made such progress toward civilization that they had in use a syllabic alphabet and a method of printing. Invented by Sequoyah,1 this alphabet of eighty-five characters, each representing a single sound of their language, is pronounced by a writer in the American Encyclopedia to be the "most perfect alphabet ever devised for any language."

While the Cherokees could not hold the Creeks and

Seminoles to peaceful ways, they would not allow them to

1 This remarkable man died in 1843. It was with this tribe that Sam

Houston lived before and after he became Governor of Tennessee.

Page 2a

MARSHALL COUNTY COURT-HOUSE, GUNTERSVILLE, ALABAMA

Page 3

pass through their domain to harrow the white settlers north of the Tennessee. The massacre at Fort Mims, Alabama, on August 30, 1813, where four hundred men, women, and children were butchered, led to the annihilation of the Creek Nation at the battle of the Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa in 1814, while the remnant of their allies, the Seminoles, sought refuge in the impenetrable marshes of the everglades in Florida, where they still survive. For twenty-four years longer the Cherokees lingered in their native land, until by treaty in 1836 they marched to the West, and their former reservation was opened for settlers.

When from a part of this Indian land the new county of Marshall was formed, Louis Wyeth, a young lawyer, journeying by stage from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to Pittsburg, by steamboat down the Ohio to Louisville, Kentucky, thence by stage to Huntsville, Alabama, and on foot for the remainder of the way (for as yet there were only trails in the Cherokee purchase), came to cast his lot with the other pioneers and to "grow up with the country."

He must have taken well with these men of the wilderness, for they made him their county judge within the first years of his advent; and, although he did not long remain on the bench--for he sought a wider field--it may truthfully be said that throughout a long and useful career he judged these, his people, to whose welfare he devoted his life. In 1848 he founded the town of Guntersville at the south bend of the Tennessee, built at his private expense a handsome brick court-house and a well-appointed jail, which were his gifts to the county and the new town, which became and still is the county-seat. As a member of the state legislature he secured a charter for a railroad "to connect the navigable waters of the Tennessee and Coosa

Page 4

rivers, with the object of securing an inland system of transportation between Mobile Bay and the vast rich region through which flowed the Tennessee and its tributaries." Of this railroad, which is now a part of the great Nashville& Chattanooga and Louisville& Nashville railroad systems, he was the originator and first president.

Page 5

II

EARLY RECOLLECTIONS

IT would be interesting to determine just when the brain-cells begin to register impressions that become fixed and are subject to the call of memory; and also with which of the senses these early registrations are associated. The brain is such an unreliable machine that the results of its operations require careful study and critical analysis before acceptance. Since older minds (which are considered mature) are known to entertain absolutely impossible schemes as fixed convictions, it is not to be wondered at that children are readily susceptible to self-deception. I have no doubt that many incidents retold as being the recollections of early childhood are nothing more than reflected images of word-pictures from older persons who really were witnesses. Only to-day a woman of more than ordinary brilliancy and of unquestionable sincerity assured me she remembered distinctly being held as a baby in her grandmother's arms when she was only a little more than one year old!

It occurs to me that since children are almost wholly animal, their earlier brain-cell registrations should be associated with alimentation, and with those to whose personal ministrations they looked for comfort and protection. It would seem but natural that one's mother should come first of all things; but with myself, I am sorry to say, this is not the case. I was four years old when my memory of things began; and my mother, who, as I now know, did little

Page 6

else but devote her time and thoughtful care to me, does not hold this precedence. My earliest recollection is of a burning house, and of Mack, one of our slaves, holding me seated on one of the front gate-posts, where I could have a good view of the conflagration. The date of this incident is known, and it enables me to determine that my brain-cells were not registering fixed impressions earlier than the fourth year. About this time I first straddled a horse and tumbled off, and that incident was indelibly impressed, as was a relation thus early established with Aunt Peggy, our negro cook, whereby without the knowledge of my mother, at about ten o'clock every morning I found myself in the kitchen eating from a small wooden tray corn-bread crusts soaked in "pot-liquor," a very filling, greasy, and satisfying mixture, which, I learned later, was a common food of the negro children of the plantations.

It is clear, then, as far as I am concerned, that the very first enduring impression was conveyed to the cells from the retina, through the so-called "sense of sight." The second was from fright, and fused with this is another impression which seems to indicate that the mind was commencing operations from within on its own responsibility. I very distinctly remember that as I was sliding off the bare back of the horse and was about half-way to the ground my good guardian Mack caught me and placed me again in position. Being scared, I asked him to let me get off and walk, but he was as inexorable as the law of gravitation. There was no getting out of it. I had to learn, and did learn, and from that time on I almost lived on horseback. This lovable slave not only taught me to ride, but he gave me a first lesson of inestimable value, which was, not to get scared and quit. The third registration, which, according to the "animal

Page 7

theory" just expressed, should have come first, was evidently conveyed through the "sense of taste," or hunger. Now, the one--to me--incomprehensible feature of this retrospection is that up to this period, and even later, I have not the slightest recollection of my parents. I was on excellent terms with the cook, and between Mack and his ward there was established an affectionate association which had already a fixed place and never ceased; in fact, grew so strong as time went on that I never wanted to be away from him in daylight.

At five years of age I was taken to school; and here again fright comes in, for I doubt if any wretch riding toward the guillotine ever suffered more than did this victim of civilization on this occasion. The teacher who preceded the present incumbent had not spared the rod; in fact, had whipped two of his boy pupils so severely that his services were dispensed with. Hearing all this from the older children, I supposed I would come in for my share from the new man, who was "part Cherokee."1

"Mr. Dave" was, however, a mild-mannered man, and, while

he kept a long hickory switch in the chimney corner near his

chair, it was only a reminder of the possibilities which might

follow bad behavior. The worst he ever did was to "thump" us on

the head with the last knuckle of one finger, and usually we got

this punishment for misspelling a word or for some shortcoming

in our studies. My first, and I believe only, experience came

within a day or two after I began. The spelling-class stood in a

row behind one of the long benches. When a word went wrong,

in order to have the correction indelibly impressed on our

1 Descended from intermarriage between a Cherokee Indian and a white

person.

Page 8

minds the culprit had to walk to where the teacher sat, project his small head in advance of the perpendicular, and receive thereon a thump which was light or heavy in proportion to the gravity of the error. My offense was "separation," and from that day to this I have never forgotten that it is dangerous to change the first "a" of the word into "e."

I had been at school for some time, and was well turned into my seventh year, when on one memorable day I made a discovery which was worth more to me than the finding of a new world was to Columbus. I discovered my mother, and incidentally began to appreciate the fact that I had a father, although at this early period he occupied a position, to my vision, very much nearer the horizon than did my newly discovered planet. The discovery came about in this fashion: a boy playmate lost his temper at something that happened between us, and in anger gave me a slap which I did not resent. At this juncture I heard a voice from a near-by window, and, turning, I saw my mother leaning out, her eyes flashing so that I could almost see the sparks flying and her cheeks as red as fire. In a tone about which there could be no misinterpretation, even by one who instinctively preferred peace to war, she asked me if the boy struck me in anger; and when I told her he had, she blazed up and said, "And you didn't hit him back?" My response was that father had told me it was wrong to fight, and that when another boy gave way to anger just to tell him it was wrong and not fight back. At this the blue bonnet of Clan-Allan went "over the border," and she fairly screamed: "I don't care what your father told you; if you don't whip that boy this minute I'll whip you!" And she looked on, and was satisfied when it was all over. I date my career from that eventful day; for I had come to the parting of the ways.

Page 8a

CHEROKEE MISSIONARY STATION, 1820

The first house built in that part of "The Reservation" in the present county of Marshall in Alabama. The author's parents were living here when he was born. It still serves as a residence and bids fair to endure for another century

Page 9

No one who knew my father ever doubted his physical or moral courage, for it was of that sublime type that held life as of secondary consideration where duty was involved, but his was the gift of gentle forbearance and kindly remonstrance to those who gave way to ungovernable and passionate word or deed. His was the way of the Nazarene and of that far-reaching wisdom of which the Proverb says: "Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace."

My mother, too, was a Presbyterian, the daughter of a minister of that faith, tender and true to her convictions of duty. Peter didn't love his Lord any less because he was human enough to lose his temper and smite off the ear of the servant of the high priest. My mother and I chose him for our patron saint, and, turning aside from the path of peace, hand in hand we trod the rougher road which led up the hill Difficulty. Upon its summit we stood at last triumphant, and thence, her beautiful face lighted up with a heavenly smile, an eternal benediction, she left me and passed down into the valley.

Time but the impression stronger makes,

As streams their channels deeper wear.

It was on one of her later birthdays I wrote:

Deal gently with her, Time! These many years

Of life have brought more smiles with them than tears.

Lay not thy hand too harshly on her now,

But trace decline so slowly on her brow

That, like a sunset of the northern clime,

Where twilight lingers in the summer-time,

And fades at last into the silent night,

Ere one may note the passing of the light,

So may she pass--since 'tis the common lot--

As one who, resting, sleeps and knows it not.

--Century Magazine, January, 1902.

Page 10

III

OUR VILLAGE BOYS

Boys are boys the world over, and we were boys, some good, some bad. None good all the time; none so bad but that if properly handled the germ of good in him could have been cultivated to an aspiration for the ideals of life and for usefulness. It is almost a maxim that children are what their parents make them. Even the influences of heredity may in large measure be eliminated if carefully studied and the value of environment appreciated, for children, like chameleons, take readily the color of that which is about them. A left-handed child, or even an adult with a strongly inherited tendency to use the off-hand, may be made just as clever with the opposite and unpreferred member by persistent training. This has been very frequently demonstrated. It is just as possible to make both members equally useful. This will be done in the years to come, and it will greatly increase both mental and muscular efficiency. What is true of a physical defect or deviation from the normal is just as true of a moral weakness. No one doubts that Ashanti infants transplanted to a Christian civilization and reared with refined and cultivated children would cease to be cannibals and savages. The domestication of wild animals and fowls is complete evidence of the influence of environment.

Among the boys of our village very few turned out bad;

Page 11

and had these few been surrounded in their homes by better example and received more kindly consideration and encouragement, even they would not have fallen by the way. Fully fifty per cent. of my playmates near my age perished in battle or from wounds or sickness contracted in the military service of the Confederacy. Most of our time up to our fifteenth year, when as a rule we were sent away to one of the well-known colleges, was spent in the long sessions of the village school with its exacting duties. A week at Christmas and the months of July and August made up the vacation period. On holidays in the fall and winter months, when the river and creeks and forests were flush with game, we were hunters and became adepts in woodcraft and the use of firearms. Often on Saturday nights, in the colder season, with the young negro boys, toward whom we white boys were always kind and considerate, with pine torch-lights and our dogs, we would roam the heavily timbered bottom lands hunting possums and coons, and at times on moonlight nights take our shotguns and seek out the wild-turkey roosts. With the full moon on cloudless nights we could even shoot turkeys, coons, and possums from the trees with the rifles, which carried only one ball. It was the practice to get the dark object between the marksman and the bright moon, sight into the moon, and slowly lower the barrel until both sights were darkened by the intervening black object, and at this moment touch the trigger. We were at home on horseback, and in the very warm days of the long summers we almost lived in the river, the temperature of which was several degrees warmer than the cold water which came in from the near-by mountain streams. Few of us could remember when we learned to swim, and the practice was general. No one seemed

Page 12

afraid of the water, nor was there ever a death by drowning. I recall that one day in the late spring, when the water in the river was still cold from the melting snows in the Virginia mountains, and it was nearly to the top of the banks, five of our group deposited our scant wardrobes, which consisted of trousers, shirt, and hat (no one wore shoes in warm weather), in the hollow of a giant sycamore and swam across the Tennessee and back for the frolic of it. In going the six hundred yards across the strong current we were carried fully a mile below the starting-point, and in returning we were compelled to walk far enough up the river-bank to offset the force of the current.

Life was not by any means all play and school with us. It was the custom with both rich and poor for every boy to do a certain amount of manual labor, plowing or other work in the garden, or chopping wood or hauling. The wealthiest planter in our county insisted that his sons work in the fields with his slaves a certain number of days each crop season. In one year I raised unaided a ten-acre field of corn. It was a wholesome custom, for it instilled in our minds an appreciation of the dignity and value of labor and made us acquainted with the use of various implements. My father refused to give me even the small "spending-money" a boy is supposed to be allowed, but he gave me every opportunity to earn what I needed by my own efforts. My chief source of revenue was cutting wood in the forests near town which belonged to him, and hauling and selling it by the wagon-load to my various regular customers. With the money so earned I became an early subscriber to Harper's Magazine and Harper's Weekly. One of the family treasures which was lost when the Union soldiers burned our home was a much-appreciated

Page 13

personal letter to me from one of the original "Brothers" who founded the great "House of Harper." Thackeray and "Porte Crayon" were contributors to the Magazine then, and in the Weekly were appearing the illustrations of the Sepoy Rebellion in India.

Thoughtful care was always given the selection of our teachers, and our community was fortunate in securing the services of Professor W. D. Lovett, of Zanesville, Ohio, a college graduate, well versed in the classics, an excellent mathematician, patient, insistent, and conscientious in the discharge of his duty. He was to me teacher and friend, and with his encouraging help and that of my father, himself at home with the classics, I was able in my fifteenth year to pass my college entrance examinations and matriculate at La Grange Military Academy in January, 1861.

Page 14

IV

HORSE AND GUN

THE boy of the old South learned to ride and to shoot almost as soon as he learned to walk.1 I began to ride when I was only four years old, and at ten was the possessor of my own horse and gun. A saddle was not permitted to beginners. Stirrups were dangerous entanglements, and when we grew up to the saddle our stirrups had leather guards to prevent the ankle from slipping through and hanging. A blanket fastened on with a surcingle was the favorite seat. For years before I was big enough to get on a horse without sidling up to a stump or a fence I rode to the creek to water my horse, or straddled an evenly balanced sack of shelled corn and made the trip twice a week to the water-mill a mile away.

I had also good practice in "riding behind" one or the other of my parents, for the newness of the country and the absence of good roads made the use of buggies or carriages practically impossible and horseback the one reliable way of traveling or of visiting our neighbors.

My first gun was a flint-lock rifle of the same death-dealing

1 The girls of the South in my day were equally at home on horseback. Both of my

sisters owned their saddle-horses, were fearless riders, and were expert with gun

and pistol. On one occasion during the war, while all the

men-folk were absent from the plantation in Lee County, Georgia, the negroes

came running in great consternation to tell my eldest sister that a huge alligator

was eating the pigs at the barn down near the lake. With an accurate shot

through the eye she killed the monster, which was over six feet in length.

Page 15

pattern as those used by the backwoodsmen of Jackson and Coffee on Wellington's Peninsular veterans at New Orleans. It was a dangerous weapon at the muzzle, and not altogether harmless at the other end. I could never entirely overcome the sense of nervousness at the flash of the powder in the priming-pan within a few inches of the eye. The bullet used was molded from bars of lead kept in stock at all frontier stores. The ball was laid in the palm of the hand, and the proper charge of powder was measured by pouring enough to make a pyramid which just concealed it. The powder was then poured into the muzzle of the barrel held perpendicularly. A bit of thick cotton cloth greased with tallow on the under side was laid over the muzzle, and the ball, placed on this, was pushed in until its top was level with the surface of the barrel, when the patch was cut smoothly across with a sharp knife. Incased in this lubricated cloth envelope, the bullet was pushed down upon the charge of measured powder near the touch-hole by means of a long, slender ramrod of tough hickory. The priming-pan was next opened and filled with powder, and the "striker" closed. The flint was so arranged that when the hammer was cocked and the trigger pressed a spring drove the flint against the striker and primer, forcing it open, and thus bringing the powder in the pan in contact with the igniting spark. These guns, now obsolete, soon gave way to those equipped with tubes for percussion-caps, and these in turn to our modern breech-loaders with percussion-cartridges.

This early training to horse and gun will explain why the mounted troops of the Confederacy for the first two years of the Civil War were notably superior to the cavalry of the North. For the third year honors were about even, and after that to the end the advantage was on the Union

Page 16

side. It took the Federal cavalrymen about two years to become expert riders and marksmen, and as such they held their own with their opponents. By 1864, when the South was depleted of live stock, the impossibility of securing good mounts or of maintaining the efficiency of those in service placed its cavalry at great disadvantage; and when to the best of horses and seasoned veterans was added the equipment with the repeating-rifle, as against the single-barreled muzzle-loader of the Confederates, it is no wonder that the men who had followed Forrest and Wheeler and Stuart and Morgan to victory on practically every battle field in the earlier campaigns could no longer successfully resist the gallant troopers of Wilson and Sheridan.

The hunting-season in the South began in the early autumn and lasted until March. In the wide ranges of uncleared woodland in the near-by mountains, and in the dense cane-brakes which grew in the rich bottom land of the Tennessee, there were wild deer and turkeys in great numbers throughout the year. I counted more than twenty of the beautiful animals in one herd within three miles of our village, and I have killed turkeys feeding in the fields and truck-gardens of our home. So plentiful were they at one time that during the breeding-season I have often heard, as I sat on our portico, the drumming sound made by the wings of the males when strutting. Squirrels, rabbits, raccoons, and opossums were abundant, while beavers, muskrats, and minks made their homes in the river's bank. Wild duck and geese came with the cold weather and remained until spring. Of the migrating birds the wild pigeon was at once the most beautiful and wonderful. The story of these birds will seem in this day like a gross exaggeration, and yet there are many persons still living who saw,

Page 17

as I have seen, the vast and countless flocks of these swift and graceful birds of passage as they whirred through the air on their southward flight, so massed that they cast a shadow like a thick cloud which shut out the sun, while the noise of their countless wings sounded like the roar of an approaching cyclone. As far as the eye could distinguish them their lines were stretched, and one flock would scarcely be out of sight before another followed. A favorite feeding-ground was the beech forest near our home, and one of the most wonderful sights I have ever beheld was the sudden and almost perpendicular descent of a vast army of these birds from a height of at least a mile to the tree-tops in the bottom lands. They simply let go, fell like snowflakes from the heavens, and alighted in such numbers that the limbs broke beneath the great weight. When the nuts were all consumed, or threshed off by the motion of their wings, the birds would swarm to the ground, many of them lost to sight in the foot-deep leaves which carpeted the earth beneath these giant trees. My father and I on one occasion picked up twenty-five pigeons killed by a single volley of our two shotguns--his a double, mine a single barreled gun. I have no idea of the cause of their disappearance; but they, like the buffalo, are now practically extinct. As late as 1870 I saw them in the White River section of Arkansas, as plentiful as they had been before the war in Northern Alabama. I am informed by a close student of ornithology that a reward of $5,000 for a pair of these birds has for three years remained unclaimed.

In the cane-brakes and thickly wooded regions we hunted chiefly on foot, but for deer and turkey and for shooting quail, the horse was in common use, while for the rare sport of fox-hunting the gun was discarded, and the

Page 18

swift horses kept the hunters always close up with the hounds.

When I became the owner of a saddle-horse it was my duty to feed and curry and take personal care of my mount; and so when the war came on, and I rode away on my beautiful Fanny, we knew each other thoroughly and were as comrades in all the exciting scenes, the times of danger in battle and of trial, with long marches and short rations, and all the hardships of an active cavalry service. Horses are not unlike their two-legged masters in the variations of character and quality; and a well-bred animal feels and shows its distinction and superiority over a common plug as does the man of gentle breeding exhibit certain qualities that mark him as not of the common run. Fanny was not only the most beautifully formed horse I have ever seen, but she possessed an intelligence almost human and could be trusted in any emergency. A whip or spur she would not tolerate. I could ride and guide her anywhere without saddle or bridle. A word, a motion of the hand, or a slight inclination of the body gave to her quick perception the direction and the gait. If the saddle was not comfortably adjusted she would stop and back one ear or the other to tell me where it pinched.

I trained her to a running-walk, at once the easiest stride for horse and rider, and day after day she has averaged forty miles over roads and trails not easy as to going. I rode her twice from my home to Rome, in Georgia, seventy-five miles, in a day and a half. When it came to running she was like the wind, and in the long speeding to safety in our scouting expeditions, when speed needed stamina to make the goal of the picket-line, she showed her mettle. As long as I rode this graceful, coal-black creature-- unmarked save

Page 19

for a white star in the center of the forehead and a white ring on the nigh hind pastern--I felt no fear of capture. On one memorable occasion she showed her heels and her rider's back in most satisfactory fashion to a squadron of Brownlow's Union Cavalry in a chase from near Triune to our outpost, some four miles away. There are times in a soldier's life when, as Campbell expresses it,

'Tis distance lends enchantment to the view.In the Christmas raid through Kentucky in 1862, when in the crisis of the pursuit and hemmed in on all sides, we were forced to ride day and night for thirty-six hours through a merciless blizzard without stopping, and then, after a rest of six hours, went on to the end of our seventy-two hours' forced march, there was not in that entire command of three thousand a horse more fit than "The Little Black"--for that was her pet name in the regiment.

In times of stress, when food was scarce and Fanny was hungry, I have often shared with her the roasting-ears of corn issued to me as my rations. At night, when we bivouacked, and the enemy was so near that every man must be ready to mount at a moment's notice, I would unspring the bit from the head-stall, and as she ate her shelled corn from the saddle-blanket I would sleep holding the halter strap and knowing full well she would never tread upon or attempt to wander from her sleeping comrade.

We Southerners rode with long stirrup-leathers, such as the vaqueros of Mexico and the cowboys of the plains and pampas use. The trained horseman with this seat is one with his mount. When it becomes necessary, the saddle pressure can be lessened by tiptoeing slightly in the stirrups.

Page 20

The pigskin-covered, shallow-seated saddle of the English, with the short stirrup-leathers and the bobbing-up-and-down style of riding, is, from my point of view and training, awkward and tiring to both rider and horse.

Our saddles were strong, and raised behind and in front, so that when firmly cinched one foot could be caught beneath the rim as the rider swung head downward on the other side to pick up any object from the ground. This we were trained to do with the horse at full gallop. At mounting we were equally expert, and from either side I could mount or leap entirely over my horse, and vault into the saddle from behind, with my pistol buckled around the waist, by placing my two hands on the horse's rump.

I said good-by to my little Fanny on June 27, 1863, and I look back on this as one of the saddest experiences of a lifetime. It was the day of the battle of Shelbyville. From near Eagleville on the Triune turnpike our regiment, then on outpost duty, was ordered to retreat hurriedly to Shelbyville. Near noon we stopped for half an hour to cool our horses' backs and rest and feed. As there was no forage except grazing, I stripped my mount of saddle and bridle and turned her into a near-by clover-field to feed at will.

When the bugle blew to saddle up I called "Fanny!" Tossing her head in the air with a whinny of recognition, she came to me at once. Leaping on her back without a bridle, I guided her by a movement of the hand toward my company's bivouac. As I approached there lay across the way the huge trunk of a fallen tree. I urged her to a canter, and she jumped over the log as I had trained her over hurdles before we began our war experiences. As she rose to take the jump the inner calk of the right fore shoe caught

Page 21

in the bark and tore the shoe loose. Unfortunately, the forge and farrier had moved on ahead; and as the enemy were in sight and pressing us, I saddled and mounted and joined in the six-mile run to Shelbyville. Within a mile the flinty bed of the macadamized roadway had done its work. Fanny began to limp, and then to lag, as her hoof was split to the quick, and I dismounted and led her. As good luck would have it, the enemy did not press us, or I should have been lost.

As I came up at last the regiment was in line of battle, and the enemy's line, a mile away, was in sight, evidently preparing to advance. As I mounted and rode into the line Major Taylor, seeing how lame my horse was, ordered me to the wagon-train and would not listen to my entreaty to let me stay. Dismounting and leading Fanny, now hobbling on three legs, and depressed beyond measure at the thought of being absent from the first big fight the regiment was to be engaged in since I had joined it, I made my way sorrowfully to the rear.

Two or three hundred yards back I came upon a member of my company who told me he was detailed to guard the wagon-train. As he had a fairly good horse and seemed anxious to take care of one too lame to be in the fight, I changed horses and equipments; and, exacting a promise that he would take Fanny to my home in Alabama, where I could find her at the close of the campaign, I mounted and rode into the line of battle just as the firing began.

The story of that fight, from two o'clock to sundown, and the disaster which overtook me at its close is told elsewhere. The great tragedy of it was, not that we were beaten or that I was left on the field, ridden down and over by the victorious enemy, but that I never again saw my

Page 22

noble Fanny. The man to whom I intrusted her reported that she grew so sore of foot she could no longer move, and he had left her in care of a farmer in Tennessee. At the close of the war my first duty was to search for my little thoroughbred, but no trace of her could be found.

Page 23

V

MAJOR, THE VILLAGE KING--LESSON FROM THE LIFE OF A

NOBLE DOG

IT is as true of dogs as of poets that they are "born, not made." Major was born great. Not that he had a proud pedigree. No more have poets as a rule: Shakespeare's father was a glovemaker; Milton's a scrivener; Spenser's a tailor; Keats's paternal ancestor kept a livery stable; and the father of Robert Burns made a very insufficient living as a gardener.

The average poet, however, knew his father--and here the comparison becomes embarrassing for Major. Genealogically he was classified as a mongrel cur, but genealogy, like the thermometer, does not always register correctly. The laws of heredity, like the laws of the universe, are as inexorable as they are wonderful and difficult of comprehension. Major was an illustration. Even as the planets of our system, after eons of divergence in space, come again in conjunction, so in this loved and faithful companion of my boyhood, born to be king of his kind in the village, there united by some mysterious alchemy certain ancestral strains, certain inherited qualities, which made him worthy of founding a dynasty.

Cast in human form, he would have been another Forrest or Jackson, a natural-born soldier. Courage and strategy and tactics were of his mental make-up, and behind these

Page 24

qualities there was a magnificent endowment of muscle and bone which made them savagely effective. Like the "Wizard of the Saddle," who said, "five minutes of 'bulge' was worth more than a week of tactics," Major believed in bulge. He always "showed fight," and never waited to be attacked. Forrest's one "general order" was: "Whenever you see a Yankee, show fight. If there ain't but one of you and a hundred of them, show fight. They'll think a heap more of you for it."

Now, Major was not particular about what the other village dogs thought of him, but he did enjoy a quiet stroll along a dogless highway. Even Cowper in his "Morning Walk" was not more fond of solitude, and as my fighter's reputation spread his meditations were rarely disturbed. At the zenith of his reign, if there was a canine in all the region round about his Judea upon whose skin he had not left the indelible register of his prowess, it was only because the other dog elected to keep between his hide and Major that distance which lent enchantment to the view. When after one of these occasional joy-chases in the wake of a fleet-footed vagrant he would return panting, with his dripping tongue hanging out of one side of his mouth, and come up to me to get the usual pat of commendation on his back, he would sit down on his hunkers and in very human fashion laugh at the comical figure the scared fugitive had cut. And it was funny enough to make even a dog laugh; for few things are more ludicrous than precipitate flight, whether there be two or four legs in action. In my soldier days I took an active part in more than one cavalry stampede, in which for the time being my comrades and I parted company with our family pride, which is another name for courage. On these occasions, if on no other, I

Page 24a

"MAJOR" AND HIS PUPIL

Page 25

was inspired with the idea of leadership, and if the inspiration was of brief duration it was only because the horse I rode was not equal to the occasion. As one after another the rattled troopers passed me in the wild scramble toward safety I had ample opportunity to observe the earnestness which characterized each individual's effort to annihilate distance. Notwithstanding the increasing proximity of the pursuers, I registered the ludicrous features of the situation, and many a time since then, with bullets and sabres eliminated, I have laughed over these scenes.

Somebody has said, or is said to have said, "All the world loves a lover," which is generally accepted as true. There is another saying that "Everybody sympathizes with the under dog." Elsewhere and in the abstract this may have been (or may be) true; but in our village it did not hold. When the bottom dog got on his feet, saw his chance, tucked his tail between his legs, and ran, every boy and man whose Christian mother or wife was not in hearing yelled at him in terms not found in the Westminster Confession, and added to the fugitive's intensity of purpose the quickening impulse of a stone or a brickbat.

Naturally, Major became the pride of the village, his prowess the talk of the neighborhood; and I, his master, shone, albeit with reflected glory. We are all more or less influenced by environment and association, and little wonder it soon came into my mind that I among my kind must keep stride with my victorious dog. He expected it of me, and when on one memorable day I licked the bully of the playground, Major jumped all over me for joy. Victors on every field, Major and his master, like Alexander, sighed for more worlds.

In a near-by settlement there was another fighting dog

Page 26

of local repute; and one summer's day when the circus came to town, the boy who owned him and his crowd walked in to see the sights, bringing with them the redoubtable pup. My chum and I were engaged in watching the busy showmen put up the big tent, when the other boys and their champion came on the scene. He was a magnificent specimen of his kind, brindle-colored, well muscled, noticeably longer in body and neck, and some two inches taller than Major. He was evidently game to the core, for he no sooner saw my pet than he bristled up, fixed his eyes intently upon him, and assumed that muscular tension peculiar to the wolf and cat tribes when about to spring. As he and they approached, the circus men, seeing that something exciting was in the air, quit work and with the crowd of loiterers attracted by the "Greatest Show on Earth" turned their attention to the battle-scene.

I recall distinctly that sinking feeling which often comes over one in the first few moments of an impending crisis, the issue of which is doubtful. I put my hand encouragingly on my companion's neck, pulled his head against my leg, and said in a low tone, "Steady, Major." There must have been some quiver of the arm or tremor in the voice which betrayed my apprehension, for, while the other valiant knight was yet some thirty yards away, my champion turned his eyes reproachfully on mine with a look which said. "Watch me." I did watch him, and, to my surprise, for the first time in his life Major did not advance to meet the enemy. I knew later his keen intelligence had cautioned him that this was the heaviest contract he had ever undertaken, and that strategy and tactics as well as courage and strength would be needed to win. I did not know it then, and as the stranger boldly and deliberately advanced

Page 27

I almost sank to the earth with shame and mortification; for Major not only failed to meet him half-way, but stood there stock-still, seemingly not wanting to fight and wagging his tail in friendly fashion, as if he were about to greet a long-lost brother. So deceptive was this assumption of friendliness, or timidity, or cowardice, that the other crowd of boys began to jeer and yell at the top of their lungs, "School-butter!" "Chicken-liver!" "Soak him!" and a lot of other objectionable constructions of nouns, verbs, and adjectives of origin as unknown as they were insulting.

It was just as this yell of exultation in anticipation of our discomfiture rose that the strategy of the master was disclosed. Unused to such a crowd and to such an unearthly noise, the invader turned his head for a moment toward his shouting mob of backers. This error sealed his doom; for in that instant, like a stone from a catapult, with lightning-like swiftness and with irresistible force, Major bounded forward, striking full-breasted against the side of the neck and shoulders of the longer dog, bowling him over and on his back. The stranger did not hit the ground before his cunning and savage foe had his throat and windpipe in the grip of a pair of jaws that never relaxed their hold until the bottom dog was half dead and hopelessly beaten, when we pulled the victor off. As Major shook himself and stood over his fallen foe in triumphant pose, ready to renew the attack, the crowd yelled and hurrahed again and again for him and me. Then we "town boys" laughed best, because we had laughed last.

Major's star, ascendant from the day he entered the arena, reached its zenith in this month, when he was four years old and when Sirius was in its glory. From this on

Page 28

his story is briefly told, and I venture to apply to my faithful friend, tried and not found wanting, a quotation from Froude's Sketch of Cæsar:

Everything which grows holds in perfection but a single moment.When the days of the sere and yellow leaf came on for this, my Cæsar, the college days came on for me; and although I did not suspect it then, I bade a long and last good-by to the home of a happy boyhood and to my loved and faithful dog. From college I went into the Southern army until the end of the Civil War, and when peace came there was no home, and Major had long since gone to the undiscovered country. After I had left, one of the slaves, ambitious to maintain the prestige of the absent member, brought into the fold a puppy, scion of my village king, who schooled him as a fighter, alas! to his own undoing.

As in the course of nature Major's muscles withered and his jaws became toothless his powerful and plucky son grew more and more resentful of the painful reprimands inflicted by his hectoring sire, and at last turned on him in mortal combat. I was told that when the servants pulled them apart the beaten but unconquered old warrior, staggering to his feet, tried in vain to renew the hopeless combat, and then, with head erect and lordly mien, passed for ever from the scene. A week later they found him dead in the edge of a forest near the town. Victory or death was the lesson that came from the spirit of this dumb creature. The savagery which he exhibited was his by nature, uncurbed and unchanged by the impossibility of a higher intelligence. That of his master, whose heart now in ripe old age, and long before he had reached the years of maturity, was filled with

Page 29

regret that even in the wild life of the frontier and in the riot of restless boyhood he could delight in these tests of animal courage and skill and strength, had less in extenuation. With all of this the moral of the lesson was not lost: "He who fights the battle of life to win or die, wins."

Page 30

VI

EARLY SCENES, RELIGIOUS AND OTHERWISE

WHILE a large majority of our early settlers were sober and law-abiding, it was inevitable that some lawlessness should prevail in the formative period of a community such as this in which I grew to manhood. Disputed pre-emption claims and other conflicts of interest led to feuds between individuals and families, in the settlement of which personal prowess and the bowie-knife or rifle were too often appealed to instead of argument or arbitration or reason and law.

In partial extenuation of these brutal combats it must be said that they usually were open fights without unfair advantage; in fact, in all the earlier bloody history of Marshall County I knew of but a single instance where one man shot and killed another from ambush. I witnessed a number of these affairs, as they often took place in the streets of my native village, where the county and district courts were held, and where from far and near the people came to political conventions, or to vote on election days, or to take part in the annual muster of the militia. During the afternoon of one election contest in which excitement ran high I saw a half-dozen different combats, while fully as many more, as I afterward learned, took place beyong my field of vision.

The business center of our village was confined to a single street, on either side of which for some two hundred yards

Page 31

the stores and shops were located. One of these stores, with a roof that sloped away from the street, the comb or highest portion of which was parallel with the edge of the sidewalk, was a favorite rendezvous for our crowd of boys, who never willingly missed those exciting scenes. Upon one pretext or another we would manage to get away from home and climb to our gallery on Kinzler's grocery. This point of vantage not only gave us a commanding view of the street, but it possessed another attractive feature, for we could peep over the edge and see all that was going on with nothing but our eyes and the tops of our heads in danger. Whenever a gun was pointed our way, or a badly aimed stone or stick flew too high, we had only to slide back a few inches and duck our heads to be safe until the gun went of or the missile had passed on. The casualties on one occasion included one man killed and a large number laid up for repairs.

Another personal encounter that came under my observation was a fight between two men, for each of whom even as a small boy I had formed a warm friendship. Passing along the sidewalk on an errand to my father's office, I came upon my two friends in excited conversation standing on a platform or open porch which served as entrance to a candyshop where I was a frequent visitor. As I stood within a few feet of them the proprietor of the shop, a very small but wiry man, stepped back quickly, drew a single-barreled pistol from his pocket, and pointed it at the other larger man, saying, "If you take a step toward me I'll kill you." The big man did not advance. He said, "I am unarmed; but if you'll wait I'll be right back, and we'll settle it." With this he hurried across the street to a dry-goods store and asked the merchant for the loan of a pistol, which was

Page 32

refused. He then picked up an ax, which he held in his right hand. With the other he seized the top of a wooden packing-box, and holding this in front of his chest and abdomen as a Kaffir would hold his pavise, or rawhide shield, to ward off a thrust from an assagai, he walked straight toward his adversary.

Meanwhile the small man was standing at the edge of the platform, pistol in hand, and pointing now directly at the big miller, who was advancing at a fast walk. The one thing which made the most vivid impression on my mind of what happened here was the self-cocking feature of the pistol. As the man pulled the trigger I saw distinctly the hammer rise just before the flash and noise of the explosion. I had never before seen a "self-cocker." My big friend interposed the box-top, through which the bullet passed before it buried itself in the muscles of his broad chest, where it remained many years, to the day of his death. As it struck him he staggered back with the ax slightly raised, whereupon the other fighter hit him a stunning blow with the heavy barrel of the empty pistol. By this time some other men had come up and separated the combatants.

This pioneer settlement was about as active and violent in matters of religion as in the occasional settlement "outside the law" of personal differences. Of the various sects the Baptists and the Methodists were about equally divided--these two outnumbering all the rest. I do not think there was a single Catholic in our community, and only one family of Episcopalians, while our immediate family furnished the Presbyterian contingent.

When my father founded the present village of Guntersville he gave a spacious lot to each sect, to be deeded

Page 33

when a house of worship was erected; but up to the breaking out of the Civil War, in 1861, there was not a single church edifice in the town. The school-house, the courthouse, and later the large Masonic Hall were used for Sunday services. Our preachers were all "circuit riders," and occupied the pulpit in turn, all the sects attending to swell the congregation. There was Sunday-school from ten to eleven o'clock in the morning, preaching from eleven to twelve, and again by candlelight, to which each family contributed a candle and a sconce, or holder, which was fastened to the wall.

The Baptists were spoken of as the "Hardshell" and "Foot-washing" sects, and were believers in total immersion; and the congregations of this particular church celebrated once or twice a year the ceremony of foot-washing. The creeks or the Tennessee River furnished holes deep enough for immersion, which usually took place in warm weather, while a piggin of water and a towel served the parson or assistants who performed the foot-washing rite.

At certain times, usually in the late summer months, in the periods of comparative leisure in a farming community after the crops were "laid by" and before "gathering-time," would be held what were called "protracted meetings" or "revivals." When the attendance proved too large for the meeting-house the congregation would move out under the shade-trees; or more frequently great arbors made of the branches of thick-leaved trees would be hastily constructed. The negroes spoke of these as "Bresh-Harbor" revivals.

The "circuit-riders," so called because they were designated to preach in a circuit of several counties, traveled their rounds on horseback, as the roads were new, ill kept, and often impassable to any kind of vehicle except the

Page 34

crude, heavy wagons drawn by oxen. At these protracted gatherings the exercises lasted three or four days, and when the excitement ran high a longer time was utilized until the supply of "mourners" and "converts" was exhausted.

The assistants to the leading clergymen were known as "exhorters," selected, it seemed to me, on account of their cleverness in appealing to the emotional qualities of their hearers. Most of them had good voices, and at certain periods in their exhortations to all who had not been converted to come up to the mourners' bench, confess their sins, and be saved, they would at the psychological moment break forth in some one of the many revival songs which rarely failed to fire the train of religious fervor or hysteria which the preacher's sermon and his own preliminary exhortation had prepared for explosion.

Of one of these songs I recall a verse or two:

Jesus my all to heaven is gone;

Glory halleluiah!

Him whom I fix my hopes upon;

Glory halleluiah!

His track I see and I'll pursue;

Glory halleluiah!

If you get there before I do,

Tell all my friends I'm coming, too;

Glory halleluiah!

And so on for a number of stanzas. When the song began he would leave the place in front of the pulpit, where he had been standing, and rush along the aisles, shaking hands vigorously right and left with all in reach, and calling them by name as "my brother" or "my sister"--there being as a rule about three sisters to one brother. There was a very large lady in our village easily moved to tears

Page 35

and hysterical sobbing, who usually gave way first and, like Abou ben Adhem, led all the rest. By the time the sermon was over she was about ready for the outburst, and when the exhorter broke loose with his "Glory halleluiah" song she would clap her hands violently together with a resounding smack, sway her body back and forth, and scream out at the top of her high-pitched voice: "Bless the Lord! Bless the Lord! Oh, my Jesus!" And with this she would follow on the trail of the exhorter, crying out to her two sons, about eighteen and twenty-two respectively, to "Come to Jesus." These young men, knowing their mother's weakness, found it convenient to sit near the door or an open window, through which a quick exit was possible when she began a rush for them.