Parkway Development and the Eastern Band of Cherokees, part 2 of 3

By Anne Mitchell Whisnant

« previous| 1 | 2 | 3 | next »

The Bauers and the Cherokee Opposition to the Parkway

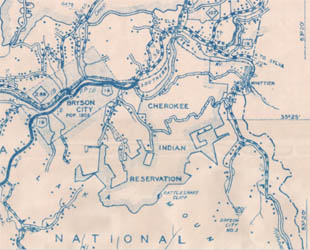

At the time the Cherokee Tribal Council rescinded its initial approval of the Parkway right-of-way through the Soco Valley section of the Qualla Boundary, the leading anti-Parkway activists within the tribe, Fred and Catherine Bauer, had only recently moved back to North Carolina from Michigan.

Fred Bauer’s mother was part Cherokee. His father, Raleigh architect A. G. Bauer, had overseen the construction of the North Carolina governor's mansion in the late nineteenth century and had designed many other structures in the capital city. Shortly after Fred's birth in late 1896, his mother died, and his father sent him to live with his mother's relatives – his great uncle and aunt, James and Josephine Blythe – on the reservation. A. G. Bauer committed suicide a year and a half later.[1]

Young Fred Bauer attended Indian schools on the reservation and the famous Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. After serving in the military in World War I, he returned to Indian boarding schools as a physical education teacher and coach. In the early thirties, he returned to the Cherokee reservation to farm and work on several relief projects, including highway construction.[2] His white wife Catherine Bauer (a Cornell graduate) taught with her husband in Indian schools in Michigan and then in the schools on the Qualla Boundary. Articulate and passionately interested in Indian issues, Catherine was a full partner in the crusade against the Parkway and the Indian New Deal. The Indian New Deal’s programs emphasizing communal land ownership and Indian cultural revival, the couple charged, would "impoverish the Indians" and "set up models of Communism for the American public to gaze upon, in the hope they will desire the same for themselves."[3]

During the spring of 1935, the Bauers battled the Indian New Deal on several fronts. As teachers, they focused their wrath on new educational policies that encouraged Indian schools to focus attention on Indian crafts, ceremonies, history, and language and emphasized vocational education rather than the more academic subjects that other North Carolina children were required to study.

The Bauers and their allies thought the route to Indian success in white America was through greater assimilation and individualism, not through a reintroduction of Indian traditions. They trusted little in the federal government and wanted to end what they perceived as government interference in Indian affairs and paternalistic treatment of Native Americans.[4]

Whipped into a frenzy by the activist Bauers, confused and understandably suspicious about the changes in federal policy, concerned about erosion of tribal farmlands, and caught in a Depression-induced spiral of fear and despair, the Cherokees elected Fred Bauer vice-chief of their tribe in the fall of 1935.

Yet Qualla Boundary Cherokees voted inconsistently in this election, choosing as principal chief a supporter of the Indian Reorganization Act and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Jarrett Blythe.[5]

Chief Blythe descended from a line of Cherokee leaders, most prominent among them his great grandfather Nimrod Jarrett Smith, who had obtained the Cherokees' corporate charter in 1889. Born in 1886 on the Cherokee reservation, Blythe – like Bauer – attended Cherokee Elementary School and Indian boarding schools: Hampton Institute in Virginia, and the Haskell School in Kansas. He worked in Montana and Detroit before moving back to Cherokee in 1927 to take jobs in the Agricultural Extension Service and in forestry for the Cherokee Indian Agency. During the Depression, he supervised road-building crews of the Indian wing of the Civilian Conservation Corps (the Indian Emergency Conservation Work Program or IECW). Blythe was Fred Bauer's cousin and the son of James and Josephine Blythe, who had raised Bauer in their home.[6]

Blythe, the Bauers and the Parkway Conflict

The 1936 election that brought both Jarrett Blythe and Fred Bauer to power in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians set the stage for several more years of negotiations, accusations, stalemates, and setbacks before a compromise Parkway route emerged.

Early on, Blythe and Bauer agreed that the Parkway should not pass through the fertile Soco Valley. From the beginning, however, Blythe looked for a compromise and, according to Catherine Bauer, initially "stated that it would be useless to protest." Even after the Tribal Council denounced the plan in the summer of 1935, he and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) agent on site at Cherokee continued to negotiate, causing a series of mixed messages to be sent to Washington from the Cherokee leadership.

Meanwhile, into the fall, articles in the Asheville Citizen suggested that the Bauers’ views (and the Tribal Council vote) did not represent the will of the Cherokees, that compromise was possible, and that the Eastern Band welcomed the Parkway and would support it if minor adjustments could be made. Federal and state officials continued throughout the fall of 1935 to strategize about how to induce the Cherokees to accept a slightly altered Soco Valley route. But in December of 1935, the Tribal Council once again rebuffed a State Highway Commission request for the right-of-way.[7]

Although twice denied, state and federal officials clung to the hope of running the Parkway through the reservation. The press mentioned the possibility of simply condemning Indian lands but noted that "Secretary Ickes, it is believed, would never consent to this." Ickes did, however, pressure the Cherokees in the newspapers, accusing the Indians of "standing in their own light" by resisting a highway that would bring them so much beneficial tourist traffic. Participants in the December meetings floated the possibility of opening the Parkway to commercial traffic on the Reservation – a tacit acknowledgment of the Cherokees' real need for a full-use public highway – but Park Service officials rejected this idea as antithetical to the Parkway’s planned “noncommercial” nature. Finally, Ickes announced that the Interior Department had compromised all it could, and that the next move would be left up to the Cherokees.[8]

The Cherokees kept sending confusing signals, however. Always vigilant, Bauer asked Ickes why, after the Council had conclusively voted down the Parkway right-of-way, state and federal officials kept pestering the Cherokees with more proposals. Meanwhile the BIA agent wrote to state officials that the Council’s action “was not an honest expression of the wishes of the people" and soon produced his own petition to Secretary Ickes purporting to demonstrate that residents of the Soco Valley wanted the Parkway and were being intimidated and misled by Bauer and his wife, Catherine, who, the petition charged, were using the Parkway issue to oppose the New Deal.[9]

Encouraged by these missives and, apparently, by favorable signals from Chief Blythe, federal and state officials drafted more proposals throughout 1936 to entice the Cherokees to grant the right-of-way. Most promising was North Carolina State Highway Commission engineer R. Getty Browning's idea of finding some fertile land in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to exchange for the farmland that the Parkway would take. Once again, the Cherokees confounded expectations and frustrated Parkway supporters by voting (narrowly: 6 to 5) against the land exchange package in their March 1937 meeting. North Carolina officials and Parkway boosters in Asheville grew fearful that continued Indian resistance might cause the hard-won western end of the Parkway–[U1]which North Carolina leaders had wrested from Tennessee after a protracted battle–to be re-routed or not built at all.[10]

The Bauers' Fears: "Real Indians," the Cultural Landscape, and Increased Federal Control

Officials at all levels of government, as well as Parkway proponents in North Carolina's business community, increasingly dismissed the concerns of Fred and Catherine Bauer as the rantings of extremists, but the Bauers' appeals struck a chord with Cherokees mindful of a history of federal abuses and suspicious of the increased federal control that the Indian New Deal seemed to many to propose.

Catherine Bauer invoked past wrongs to question current policies: "Does the Parkway," she demanded in a 1935 letter, "contemplate celebrating the 100th anniversary of the GREAT REMOVAL by another GREAT REMOVAL?" Even Jarrett Blythe, chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, admitted during a Congressional hearing over the matter that those who feared that turnover of the Parkway right-of-way was a first step towards federal confiscation of the entire Qualla Boundary for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had not forgotten the removals of 1838.[11]

Cherokee misgivings were well founded in light of current events as well. The National Park Service was at that very moment removing white Appalachian residents from their homes as it took over their lands for incorporation into the Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah National Parks. Furthermore, early plans for the Smokies had proposed incorporation of some Cherokee lands, and many Cherokees doubtless suspected that federal officials had not completely abandoned that idea.[12]

For their part, the Bauers saw the Parkway plans as interwoven with the agenda of the Indian New Deal. In their view, the federal government would first convince Indians to revive their crafts and traditional ceremonies, and would then bring a scenic highway through the reservation and turn Cherokee land into a park exhibit controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).[13]

This concern was not far-fetched. A 1934 brochure outlining North Carolina's arguments for its preferred Parkway route had noted that “This route also ends at the Cherokee Indian reservation. . . . These Indians lead an agricultural life but their cabins, their council house, the baskets, pottery, bows and arrows they make, their dances and games have changed but little from what it was when the white man first came into their mountain fastness. These people form a picturesque and interesting feature for visitors to the Smoky Park."[14] And the Charlotte Observer in 1938 tantalized potential Parkway visitors with images of "closemouthed Cherokee Indians of brownish, reddish, and coppery hues . . . [who] will furnish the crowning touch of interest to everyone who motors over the Blue Ridge parkway."[15]

Thus while the Bauers embraced the general Cherokee enthusiasm for tourism-oriented development, they were troubled by the thought of government-directed tourist programs capitalizing on Cherokee traditions. They especially criticized the BIA-sponsored cultural revivals and the crafts cooperatives planned as part of the Indian New Deal. In a hearing before Congress, Fred Bauer contended that "the Cherokee Indians, who . . . have adopted most of the white man's civilization, are being re-educated to be Indians. Tribal regalia of feathered headdresses, beaded costumes, moccasins, tom-toms, forgotten ceremonial dances, Indian arts and crafts, and even the Cherokee language is being taught to the children and revived among the adults." The BIA, he added, "whose ideas of rehabilitating the Indians extend no further than to turn him back into a primitive state, hopes to exploit the Indian further by commercializing him. . . . All of these elaborate plans hinge upon the Parkway."[16]

The Bauers proposed that without the Parkway and Indian Bureau control, the Cherokees could develop and run their own tourist industry along state highways while gaining other income from the leasing of reservation land to tourist operators who had the capital to open stores and accommodations.[17] They compared a BIA-controlled Cherokee unfavorably to its neighbor Gatlinburg, where, Catherine Bauer wrote, prosperity came due to “the investment of private capital and the initiative of people who believed in private enterprise and were willing to proceed in the traditional American manner of doing business.” The same capitalist magic could work at Cherokee, she concluded, for “if Indians are ever permitted to live like men instead of children, they will readily take their places in the American scheme of things, and will have no need of [a BIA] to wet nurse them along.”[18]

« previous| 1 | 2 | 3 | next »

2 Adams, Education for Extinction, 48-59 323; Coleman, American Indian Children at School, 1850-1930; Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20628; Finger, Cherokee Americans, 85; Bauer, Land of the North Carolina Cherokees, introductory page.

3 Waynick, "Half Indian Is Chief"; Finger, Cherokee Americans, 85, 89; Catherine Bauer to Senator Josiah W. Bailey, 22 January 1937, Bailey Papers, Box 314, DU.

4 Finger, Cherokee Americans, 82, 85-87.

5 EBCCM, 7 Oct. 1935 meeting; Finger, Cherokee Americans, 85-91.

6 Finger, Cherokee Americans, 93; John Parris, "Retiring Cherokee Chief Jarrett Blythe Honored," Asheville Citizen, 4 October 1967; "Death Claims Noted Cherokee Leader, 90," Cherokee One Feather, 20 May 1977; Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20629.

7 Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, NCSA; Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20618-19; Jack Jackson, Henry Bradley, and Meroney French, Cherokee Tribal Council, to Harold L. Ickes, 25 June 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; A. E. Demaray to Mr. MacDonald and Mr. Vint, 26 September 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2730; From SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives: Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, and RGB to Capus M. Waynick, 29 October 1935; Capus M. Waynick to Harold L. Ickes, 20 November 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; John Collier to Harold L. Ickes, December 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; Bauer, Land of the North Carolina Cherokees, 41; Harold W. Foght and Jarrett Blythe to Harold L. Ickes, 24 June 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; EBCCM, 13 Dec. 1935 meeting.

8 Walter Brown, "One-Fourth of Parkway Work Now Allotted," Asheville Citizen, 17 December 1935, City Edition, 1;"Ickes Says Cherokees Should Favor Parkway," Asheville Citizen, 18 December 1935, City Edition, 1; RGB to Harold L. Ickes, 18 December 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; A. E. Demaray to Harold L. Ickes, 24 December 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734.

9 Fred B. Bauer to Harold L. Ickes, 27 December 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; Harold W. Foght to RGB, 30 December 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives; RGB to Harold Foght, 4 January 1936, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives. Harold W. Foght to Harold L. Ickes, 23 January 1936, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; Cherokee Indians to Harold L. Ickes, 14 January 1936, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734; Harold W. Foght to John Collier, 30 January 1936, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734.

10 See correspondence in RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734: John Collier to Harold L. Ickes, 5 March 1936; Harold L. Ickes to A. E. Demaray, 9 March 1936; J. R. Eakin to Director, National Park Service, 9 March 1936; J. R. Eakin, "Report on Proposed Exchange of Lands Between Great Smoky Mountains National Park and Quallah Indian Reservation," 19 March 1936. See also Walter Brown, "Submits Plan For Cherokee Parkway Link," Asheville Citizen-Times, 17 May 1936, A, 1; Editorial, "Should Solve the Problem," Asheville Citizen, 18 May 1936, 4. "Foght Predicts Land Swap Will Please Indians," Asheville Citizen, 20 May 1936, 1, which detailed the terms of the swap as a transfer of 1547 acres of land in the Ravensford area of the GSMNP for 1202 acres of the reservation near Smokemont. The Indians would have had to agree to sell to the state at "a fair price fixed by the secretary" the right-of-way for the Parkway. So the exchange wouldn't have been for the Parkway lands directly, but would have been part of a package deal. In addition, the article reported that perhaps twelve families would have been uprooted by the deal. It also noted that, to sweeten the pot, Ickes had promised "to modify his own regulations" and give Indian workers preference on all Parkway work within the reservation. Legislation needed to allow this land swap was introduced in mid-1936. See House, Committee on Public Lands, House Report No. 3003 to accompany H.R. 12789; EBCCM, 15 March 1937 meeting. This package was originally presented to the band at the December 1936 meeting, but was tabled until the March meeting. See EBCCM, 10 December 1936 meeting. See also Harold W. Foght to William Zimmerman, Jr., 17 March 1937, RG 75, Series 6, Box 10, NARA SE; Frank L. Dunlap to Josephus Daniels, 7 June 1937, SHCRWD, Box 2, NCSA; and George Stephens to Frank L. Dunlap, 1 July 1937, SHCRWD, Box 2, NCSA.

11 Catherine A. Bauer to Capus M. Waynick, 20 October 1935, SHCRWD, Box 15, North Carolina State Archives; House, Committee on Public Lands, Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway, 47.

12 Dunn, Durwood. Cades Cove: The Life and Death of a Southern Appalachian Community, 1818–1937. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988, 241-54; Powers, Elizabeth, with Mark Hannah. Cataloochee: Lost Settlement of the Smokies. Charleston, S.C.: Powers-Hannah, 1982, "Cataloochee Homecoming," 8-17; and Brown, "Smoky Mountains Story," 142-50. Brown's study was later published as The Wild East and is the fullest available study of the removal of over 5600 people from the area taken into the Park.

13 Bauer, Land of the North Carolina Cherokees, 39; "Cherokee Indian Explains Opposition To Scenic Road," Charlotte Observer, 15 January 1939.

14 North Carolina Committee on Federal Parkway, "Description of a Route through North Carolina Proposed as a Part of the Scenic Parkway to Connect the Shenandoah National Park with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park," 1934, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2711.

15 Hoyt McAfee, "Scenic Grandeur Along Crest Way," Charlotte Observer, 10 July 1938 (quotation); Editorial, "Progress of the Parkway," Asheville Citizen, 14 December 1935, 4; Roy, "Rambling Around the Roof of Eastern America"; and Sass, "Land of the Cherokee."

16 House, Committee on Public Lands, Establishing the Blue Ridge Parkway, 74; Harold W. Foght and Jarrett Blythe to Harold L. Ickes, 24 June 1935, RG 79, CCF7B, Box 2734, NARA II; Bauer, Land of the NC Cherokees, 38-39.

17 Senate, Subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, Survey of Conditions, 20707; Bauer, "Problems of the Indians."

18 Bauer, "Problems of the Indians"; Tooman, L. Alex. “The Evolving Economic Impact of Tourism on the Greater Smoky Mountain Region of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina.” Ph.D. diss., University of Tennessee at Knoxville, 1995, 223, 242-43; and Finger, Cherokee Americans, 104 and 138.